| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

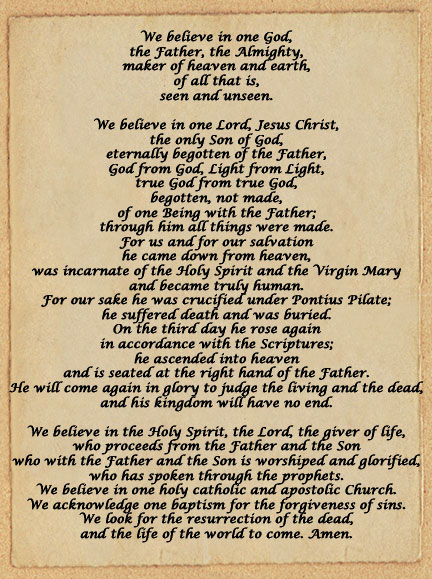

The Protestant Mary?

Reflections on the TIME Cover Story

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2005 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com . Thank you.

A TIME-ly Coincidence

Part 1 of the series: "The Protestant Mary"

Posted at 11:30 p.m. on Wednesday, March 16, 2005

On Monday afternoon I was listening to a CD I had recently purchased: The Passion of the Christ: Songs (Original Songs Inspired by the Film). This collection includes pieces from more than a dozen musicians, most of whom are not generally considered to be "Christian artists." One song, "New Again," was written and performed by country music stars Brad Paisley and Sara Evans. Though country music isn't usually my cup of tea, I was struck by the inspiration and tenderness of this song, which is a duet sung as if by Jesus and his mother as he approaches the cross. It includes these lyrics:

Mother, do not cry for me

All of this is exactly how it's supposed to be

I'm right here. Can you hear my voice?

My life, my love, my Lord . . . my baby boy.

As they nail me to this tree

Just know my father waits for me

God how can this be your will?

To have your son and my son killed?

To hear a clip from this song, click here (264 K, .mov clip). To listen to samples from other songs and/or to purchase this album from Amazon, click here.

|

|

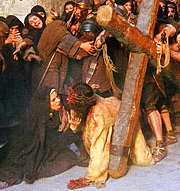

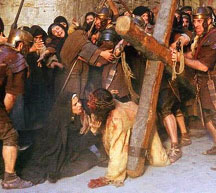

As I listen to this plaintive song, I found my heart moved by the thought of what it must have been like for Mary to witness the crucifixion of her son. I was also intrigued by the fact that she could indeed ask God, "How can this be your will, to have your son and my son killed?" Nobody else is history could ask that question.

From this point I began to reflect upon how Mary has been so much the attention of Protestant and evangelical discussions of Christ's death in the wake of Mel Gibson's film The Passion of the Christ. Millions of Christian who might never before have given Mary the slightest thought when they remembered the Cross were now envisioning her agony and faithfulness. "How odd this is," I thought to myself, "Who'd ever have thunk it?"

I listened to the "New Again" track a couple more times on Tuesday, playing for my wife, who found it quite moving even though she's not much of a country music fan either. Then, late on Tuesday evening, I surfed by Hugh Hewitt's website, only to find the following:

Strangely enough, I had not seen TIME magazine because mine had not yet been delivered. (It still hasn't shown up as of Wednesday evening.) I quickly checked out the TIME material online, however, and decided to pick up Hugh's challenge. I must say that I found it curious that what I had been pondering in my private reveries was all of a sudden emblazoned on the cover of TIME.

I plan to blog about the TIME material, mostly David Van Biema's article, "Hail Mary." I'm doing this not only because Hugh Hewitt thinks it's a good idea, though Hugh's intuitions about blogging are usually worth following. I also think there is some good grist here for our theological and devotional mill. I agree with Van Biema's basic thesis that Protestants are much more open these days to thinking about Mary. And I think that those of us who are Protestants (including evangelicals) can learn a few valuable lessons by looking closely at what's going on here.

I do not believe, however, that Van Biema gets many of the implications right. As I'll explain later, he seems to have read the data in an idiosyncratic fashion, as if he were more eager to prove his point than tell us what's really going on with Mary and the Protestants. But, of course, I may be projecting my own bias onto the data as well. You'll have to read this series to decide who's right.

But, lest I sound too negative about Van Biema's article, I did find it to include some fascinating tidbits regarding Mary in Protestant piety. And I appreciate the fact that Van Biema didn't fall into the debunking mode that plagues secular media accounts of Christian beginnings. He did not, for example, waste words trying to debunk the historicity of the gospels. In fact, when it comes to the Blessed Virgin Mary, Van Biema seems quite willing to accept the gospels as historically accurate sources. Imagine that! (I contrast this with his article on the birth of Jesus last December, which, though better than its Newsweek counterpart, still presented a hypercritical look at the nativity stories in the gospel. I put up an extended blog series on this topic: The Birth of Jesus: Hype or History?)

Tomorrow I'll lay out Van Biema's thesis and begin, as Hugh suggests, to deconstruct it. But before I sign off, I want to end with a bit of a challenge.

Van Biema rightly points out the influence of The Passion of the Christ on Protestant (including evangelical) reflection on Mary. Besides this movie, what else in the last two decades do you think has had a major impact on Protestant views of or feelings about Mary? I think Van Biema missed something quite significant. Can you guess what I'm thinking of? You can e-mail me your ideas, or, better yet, put them in the guestbook.

The TIME Cover Story: An Overview

Part 2 of the series: "The Protestant Mary"

Posted at 11:30 p.m. on Thursday, March 17, 2005

The cover of this week's TIME magazine proclaims: "Hail, Mary: Catholics have long revered her, but now Protestants are finding their own reasons to celebrate the mother of Jesus." The cover story, written by David Van Biema and entitled: "Hail, Mary" adds this bit of explanation: "She was there at the Cross. Yet Protestants seldom talk about Jesus' mother at Easter – or at most other times. But they are starting to now."

Van Biema's basic thesis is that, after years of silence among most Protestants, Mary (the Blessed Virgin mother of Jesus, not the Magdalene) is making a comeback. Van Biema brings forth a variety of data to support his claim:

• A Presbyterian pastor in Xenia, Ohio, plans to preach on the Annunciation to Mary during his Good Friday service this year, owing to an overlap on the calendar.

|

|

• Beverly Gaventa, a professor at Princeton Theological Seminary (also Presbyterian) has written a book on Mary and edited a collection of essays on Mary by feminist biblical scholars.

• Articles favoring new attention for Mary have appeared in Christianity Today (evangelical Protestant) and The Christian Century (mainline or liberal Protestant).

• A sermon on Mary was preached in a "mighty pulpit" by John Buchanan, senior pastor of Chicago's Fourth Presbyterian Church.

• Several theologians say Mary is gaining popularity among Protestants.

• Mary plays a significant role in the New Testament gospels.

• An evangelical writer has devoted a chapter of his book to Mary's Magnificat.

• Icons of Mary are showing up on the walls of Protestant divinity schools.

• Some Protestants have a deep personal devotion to Mary.

• The influx of Hispanics into American Protestantism is having a small impact on interest in Mary.

If you add all of these bits of data together, I think you have evidence for a growing openness among Protestants to take Mary seriously insofar as she is portrayed in Scripture. Traditional squeamishness about the Blessed Virgin among Protestants, stemming no doubt from the way she is revered among some Catholics, seems to have been replaced by a freedom to examine Mary's presence in Scripture and to take more seriously her unique place in Christian history and theology.

I agree with Van Biema's basic thesis. It fits the evidence he brings forth and my own experience as a pastor. (Though I must note that Presbyterians are disproportionately represented in Van Biema's article. Since I'm a Presbyterian, my experience might be skewed in the direction of Van Biema's evidence.)

But, apart from my agreement with this basic thesis, I find myself perplexed by some of what Van Biema believes to be true. And I think he fails to mention some of what is most important and relevant. So, in the rest of this series I'll critique what I think needs criticism and add what I think is missing.

I must admit that I have downplayed Van Biema's thesis somewhat. After surveying the evidence before him, he actually says this: "[These factors] may eventually accelerate progress toward a pro-Marian tipping point—on whose other side may lie changes not just in sermon topic but in liturgy, personal piety and a re-evaluation of the actual messages of the Reformation." Now that's quite a claim, and it's one I intend to evaluate quite carefully. It sure seems to go way beyond the modest evidence Van Biema has brought forth. But this will come later in the series, after I've done some basic spadework.

One of the things I find perplexing about Van Biema's article is his suggestion that there has recently been a pervasive Protestant anti-Mary conspiracy. Let me quote several lines from his article so you can see this conspiracy theory writ large. The words are Van Biema's; the italics are mine.

"Beverly Gaventa . . . has portrayed Mary as the victim of 'a Protestant conspiracy of silence: theologically, liturgically and devotionally'."

According to author Kathleen Norris, "We dragged Mary out at Christmas . . . . . [and] denied [her] place in Christian tradition."

The "long-standing wall around Mary appears to be eroding."

A "growing number of Christian thinkers . . . have concluded that their various traditions have shortchanged [Mary] in the very arena in which Protestantism most prides itself: the careful and full reading of Scripture."

Over time, Protestant anathemas against Mary lovers gave way to a kind of sullen neglect of the Virgin.

While Mary's role in the Nativity is recalled dutifully each December, largely overlooked is the subsequent presentation of Jesus at the temple . . . . Also neglected are her maternal frenzy when her 12-year old son goes missing . . . and her role at the wedding at Cana.

The most striking omission, at least from Protestant sermons, is a recognition of the import of her role at the Cross.

Almost all the revisionists find Mary's presence at the Crucifixion inspiring in a way that their denominations seldom acknowledge.

[In Mary there is] a central Christian image of love . . . that Protestantism never officially repudiated but from which it has been estranged almost from the start.

Wow! And to think I've been a Protestant for four decades – and a Presbyterian pastor for two – without ever knowing about this conspiracy against Mary. Either Van Biema knows a lot more than I do, which is possible, or else he's been hanging out too much with Oliver Stone.

Historically, there was a lot of negativity between Protestants and Catholics, and this surely inspired Protestant resistance to giving Mary much attention. But in my lifetime and in my experience of Protestantism (Presbyterian, Mennonite, Assemblies of God), Mary has been a minor yet welcome part of church life. Yes, she may have received less attention than she deserved. But I'd hardly characterize this as a conspiracy of silence, sullen neglect, and estrangement. Benign neglect would be more like it, or perhaps innocent ignorance.

Never in my Christian experience has anyone "dragged out" Mary at Christmas or "recalled dutifully" her role in the Nativity. On the contrary, I'd say that Mary has played a central and joyful role in my experience of Christmas, as a boy, as a worshiper, and as a pastor. Moreover, I have heard sermons and teachings involving Mary ever since my youth. I remember a marvelous sermon I heard several years ago in which Mary's reception of God's Word was used as an example of how we should receive God's Word in our own lives.

I've included Mary in my own preaching at several points. For examploe, eleven years ago in a Good Friday service I was working my way through the seven last words of Jesus. When I got to the third word, "Woman, behold they son! . . . Behold thy mother!" I reflected on Mary's pain as a mother. I related this to the suffering of mothers in my church who had lost their children, and to the statement by my grandmother when her son (my father) was dying, "No mother should ever have to experience the death of a child." I talked about how Jesus, though the Son of God, was also a beloved son of Mary, and how this fact reminds us of his humanness.

When I preached this Marian stuff, it never occurred to me that I was doing anything groundbreaking or edgy. I didn't think I was being particularly original or profound. I had heard things like this before in my Protestant experience. I'll bet if I were to ask my pastor friends, many of them have made similar points on similar occasions. Mentioning Mary in the context of Good Friday is common, at least in my experience. And, I might add, I didn't receive even the tiniest criticism for speaking about Mary in this way on Good Friday. My congregation received it with open minds and hearts. It just wasn't a big deal. Nobody from TIME magazine even bothered to quote me.

So, though I think Van Biema is onto something, I find his conspiracy theory to be exaggerated. I realize, of course, that he's trying to make his story more interesting. The facts rarely sell magazines. And Van Biema got the cover of TIME, for goodness sakes. But his rhetoric goes far beyond the evidence, in my opinion. Moreover, as I'll explain soon, he misses some insights that seem to me to be worth much more attention.

A Pro-Marian Tipping Point? Evaluating the Evidence

Part 3 of the series: "The Protestant Mary"

Posted at 9:30 p.m. on Friday, March 18, 2005

In yesterday's post I summarized the evidence David Van Biema amassed for his argument that Mary's popularity is growing among Protestants. As I mentioned, he actually goes beyond this observation to suggest that Protestants may be on the way to a "pro-Marian tipping point" that will impact Protestant liturgy, piety, and even the "actual messages of the Reformation." Quite a claim, I must say.

If you look critically at the evidence Van Biema puts forth, you'll see that it's rather thin. The author himself admits that though "arguments on the Virgin's behalf have appeared in a flurry of scholarly essays and popular articles," they are "not yet [being preached] in many churches." In fact the specific churches Van Biema mentions are few and hardly representative of mainstream Protestantism, let alone evangelicalism. But Van Biema has one "big gun," as it were:

[Arguments on the Virgin's behalf are being preached] not just at modest addresses like [a 300-member Presbyterian church in Ohio] but also from mighty pulpits like that at Chicago's Fourth Presbyterian Church [a 5,000-member church and growing], where longtime senior pastor John Buchanan recently delivered a major message on the Virgin ending with the words "Hail Mary . . . Blessed are you among us all."

Now this seems like a weighty piece of evidence. One of the largest and most influential churches within the Presbyterian Church USA (one that is center-left in theology, by the way) seems to be moving in the direction of exalting Mary. The senior pastor preaches a sermon on Mary, ending it with a gender-inclusive "Hail Mary." Wow! Maybe we actually are moving toward some sort of a "pro-Marian tipping point."

I thought it would be worthwhile to examine Rev. Buchanan's actual sermon, so I surfed over to the Fourth Presbyterian Church website. It's elegant and full of helpful information, including online sermon transcripts and PDF versions of recent worship bulletins. It didn't take long on this well laid out website to find Buchanan's sermon on Mary. |

|

| |

The classic sanctuary of Fourth Presbyterian Church in downtown Chicago.

|

Reading his sermon gave me a feeling of déjà vu. Much of it sounds awfully similar to Van Biema's article. No doubt it was a major source for the TIME writer, who quotes two more times from Buchanan's sermon, in addition to the "Hail Mary" line cited above:

"We're inclined, you and I, to think about our faith in terms of ideas and propositions and truth claims. [Yet] Mary reminds us that our faith is a response to a love that was expressed not in a carefully reasoned treatise but in a human life."

Mary, he said, is "a reminder to the mother whose son was killed in Iraq last week ... [to] children and wives and husbands who wait in fear and in hope. Let her be a reminder of the mercy and compassion and nearness of God."

It's worth noting that Buchanan didn't actually use the word "Yet" in the "We're inclined" quotation. Instead, he used "And." Van Biema rightly puts "Yet" in brackets, but in so doing shows his hand. Buchanan himself sees Mary as adding something to propositional faith. The TIME writer's "Buchanan" sees Mary as somehow oppositional to propositional faith, which far juicier but less accurate.

Buchanan's main thesis is that it's "time for Protestants to make a place of Mary." Okay, but what place? This is the key question. Does Buchanan's place for Mary confirm Van Biema's thesis of a Protestant "pro-Marian tipping point" that will impact Protestant liturgy, piety, and even the "actual messages of the Reformation"?

I've read Buchanan's sermon twice, and I just don't see it. Not at all. After calling Protestants to give Mary her place, Buchanan then explains exactlhy what place he means. Mary is to serve as "a reminder" for Protestants. She is not a focus of essential doctrine, not a heavenly queen who prays for us, not a co-redeemer alongside of Christ, and certainly not someone who should play a major role in our worship and piety. Of what does Mary remind us, according to Buchanan? She reminds us:

• "Of how grounded in life this faith of ours is."

• "That God cares deeply about the human condition. . . . Let Mary remind us of the wideness of God's mercy."

• "That God can use modest men and women who don't seem to have much to commend them . . . to do the most important work."

• Of "the profound compassion of God. . . . Mary has reminded the faithful that God is also infinite compassion and infinite love."

• "Of the mercy and compassion and nearness of God."

• "Of the love that came down at Christmas to be with us and to keep us every day of our lives."

None of these reminders focuses on Mary and her specialness. All but the first, which is about faith, focus on God. The last is about Jesus, who is God's "love that came down at Christmas. So Rev. Buchanan may be using Mary in an unusual way (through, frankly, I doubt it's that unusual). But his theological points are solidly Protestant and biblical. Mary is mostly a marvelous reminder of who God is and how God acts.

From this sermon we would hardly expect there to be any significant changes in the liturgy, piety, and theology of Fourth Presbyterian Church. And from what I can tell, this expectation is confirmed by the facts. I downloaded several orders of worship from the church website (from 2004 and 2005). In these, Mary shows up in very traditional Presbyterian garb. She's mentioned in the Apostles' Creed and in Christmas carols as the composer of the Magnificat or the mother of Jesus. That's it. No "Hail Mary's." No songs to Mary. No veneration of the Virgin. Just good ol' Protestant Mary.

"Ah," you say, "but what about the ending of the sermon. Buchanan's inclusive 'Hail Mary" is telling, isn't it?" Well, not exactly, if you place it in a larger context. On December 5, 2004 Rev. Buchanan preached a sermon entitled "Mary," which ended with the words, "Hail Mary . . . You are blessed among us all." Van Biema tells us this. But what he fails to mention is the fact that on December 12, 2004 Rev. Buchanan preached a sermon entitled "Joseph." After analyzing Joseph's situation and praising him for his exceptional goodness and responsibility, Buchanan concludes with these words: "So, yes, 'Hail Mary,' and 'Hail Joseph, blessed are you, as well, among us all.'"

Now that changes our perspective more than a little, don't you think? Buchanan utters "Hail Mary" on December 5th and "Hail Joseph" on December 12th. Does this sound like we're drifting toward some sort of Catholic-like reverence for Mary? Hardly. In fact the opposite is true. Even as the December 5th sermon gives Mary a Protestant promotion, the December 12th sermon promotes Joseph to the same level as Mary. Joseph and Mary, according to Buchanan, both deserve to be hailed. How many Marian Catholics do you think would be happy with the preacher saying "Hail Joseph, blessed are you among us all" in church?

I don't see any "pro-Marian tipping point" here. I don't see any changes in liturgy, piety, or theology. What I see is an appropriate, mainline Protestant use of Mary, in which her experience points to the goodness of God. Morever, I see a leveling of the playing field between Mary and Joseph, where both can be addressed in a sermon, but not in worship or prayer, with "Hail." If anything, I would take the actual evidence from Fourth Presbyterian Church as disconfirming Van Biema's main thesis. A little more attention for Mary, sure. But a "pro-Marian tipping point"? Hardly, especially when the classic Marian greeting is now made to include Joseph.

Van Biema draws upon another church from Chicago to support his thesis. Given the fact that he places this example at the end of his article, a rhetorical point of emphasis, it stands as his strongest example. I'll examine it more closely in my next post.

The Influence of La Virgen?

Part 4 of the series: "The Protestant Mary"

Posted at 11:30 p.m. on Saturday, March 19, 2005

In my last post I examined some of the evidence David Van Biema presents in support of his argument that Protestants may be on the way to a "pro-Marian tipping point" that will impact Protestant liturgy, piety, and even the "actual messages of the Reformation." Although his article in TIME magazine relies quite heavily on a sermon preached by John Buchanan, a Presbyterian minister in Chicago, a close examination of that sermon suggests that Van Biema has seen much more than the evidence would allow. Buchanan's sermon reveals, at most, a greater openness among Protestants to think of Mary as a human reminder of God's grace. But this is hardly news.

It's from another church in Chicago that Van Biema seems to draw even more proof for his thesis, given the placement of this example at the conclusion of his article. Here are the TIME excerpts in which we find this example:

In the end, Mary's role may be less influenced by [Protestant theologians] than by a group only now beginning to make its considerable Protestant presence felt. A man stands at the lectern at the El Amor de Dios church on Chicago's South Side reading in Spanish, tears streaming down his cheeks. His text is a treatment of the Virgin Mary from one of the Bible's apocryphal books. Another congregant follows, reciting his own verses to the Virgin from a dog-eared notebook filled with tiny, precise printing. Flanking the altar are two Mary statues with fresh roses at their feet, and hanging from the hands of the baby Jesus is a Rosary. The altar cover presents the church's most stunning image: Mary again, this time totally surrounded by a multicolored halo, in the traditional iconography of the Our Lady of Guadalupe. The church is Methodist.

"Right now Marianism is not a front-burner issue for people revising liturgy in major denominations," says Marian agitator [and Lutheran theologian Carl] Braaten. "But I think it will come in because of the great influx of Hispanics into Protestantism." Indeed, there are some 8 million Protestant Hispanics in the U.S., with the count climbing. Many hail from Mexico, where the Guadalupan Lady is as much a national icon as a religious one, and are from historically Catholic families. El Amor de Dios' pastor, the Rev. Jose Landaverde, says his Marian additions are "mainly cultural." But "in the context of this neighborhood and embracing these people, this is what they need. "Our Lady, he says, "creates hope." Church rolls have risen, Lazarus-like, from a dozen people to several hundred since he added the Mary elements.

Some of Landaverde's fellow Methodists dismiss this new wrinkle. The Rev. Enrique Gonzales, pastor of El Mesías United Methodist in nearby Elgin, wrote a piece accompanying Christian Century's Mary story asserting that Latin Protestants are especially wary of such enthusiasm because "the Gospel of Jesus Christ is not actually introduced to Roman Catholic people in Latin America because only Marian doctrines are taught to them." Yet Ted Campbell, president of a local Methodist seminary in Evanston, Ill., says, "This is a phenomenon that's growing in a lot of Protestant churches." When he first heard what was going on at El Amor de Dios, he confesses, he thought, "Cool."

I did a little surfing around to confirm Van Biema's picture of what is happening at El Amor de Dios church. Indeed, it seems accurate. Last December 12th an article appeared in the Chicago Tribune with this title: "Methodist church stirs controversy with statue." The article explained how El Amor de Dios church had erected a statue of the Virgin of Guadalupe a year ago, chasing longtime members from the church, but drawing new crowds. This article also confirmed another point made by Van Biema, namely that other Latino Methodist leaders did not approve of the introduction of a statue of La Virgen into a Methodist worship service.

The pastor of El Amor de Dios church, according to Van Biema, defended his use of Mary as "mainly cultural" (meaning "not religious"? Wouldn't this count against Van Biema's thesis?). It should be noted that this pastor, Rev. Jose Landaverde, was a student pastor at the time of the introduction of Mary, and that he had once been a Roman Catholic seminarian – not exactly your run-of-the-mill Methodist minister.

Van Biema has obviously been influenced in his evaluation of the data by the Lutheran theologian Carl Braaten, whom Van Biema calls "a Marian agitator," a title that doesn't exactly suggest objectivity on Braaten's part. Braaten believes that the influx of Hispanics into America will, in time, lead to the revision of worship in mainline denominations. That may well be so. |

|

| |

Mary as the Virgin of Guadalupe, who is said to have appeared to a poor native Mexican in 1531. This recent rendering of the Virgin was painted by Hollister (Hop) David. For this and other of this works, click here. |

But I find it curious that Van Biema himself records two reactions to the Marianism of El Amor de Dios. The Anglo president of a Methodist seminary (who, incidentally, just announced his resignation as of March 2005, though this fact has nothing to do with our current investigation) thought the introduction of Mary into the Methodist church was "cool." On the contrary, a leading Hispanic Methodist pastor not only opposed the practice, but also wrote an eloquent defense of his position for The Christian Century. According to Enrique Gonzales, pastor of El Mesías Methodist Church, "the practical theology in the life of Catholicism in Latin America promotes the adoration [worship] of Mary." Thus Methodists and other Protestants restrict liturgical veneration of la Virgen. Gonzales concludes his article:

There is a place for Mary in the life of the Protestant church, but it is as an equal to all the other characters described in the Gospels (Peter, John, Mary Magdalene, Lazarus, etc.). Mary will be part of the life of the church until the day that the church ends its ministry on this earth. However, Mary is like you and me, just another good believer who believed in the only Son of God as Savior.

I've known Hispanic Protestant pastors who are more strongly opposed to things they regard as Roman Catholic – including the veneration of Mary – that I am because they have personal experience of the extent to which Mary can dominate Latino piety, "even to the point of claiming the supremacy of Mary over Jesus Christ," to quote Enrique Gonzales. Thus I'm disinclined to accept the views of Braaten and Van Biema on the growth of Marian piety within Protestantism just because Hispanics are moving to this country. It may turn out that having more Hispanics in Protestant denominations makes them less open to Mary, not more. It appears that both Landaverde and Gonzales have seen their approach to Mary draw Hispanics to church. Yet, at least as far as I can tell, Gonzales is more thoughtful in his rejection of Marian veneration than Landaverde is in acceptance of it. (This may not be fair to Landaverde, however, since I have little to go on besides a couple of quotes in articles.)

I want to conclude this post by returning once again to Van Biema's description of Marian veneration in El Amor de Dios church. In that description we see a man at the lectern reading "a treatment of the Virgin Mary from one of the Bible's apocryphal books." Another man recites "his own verses to the Virgin."

I must point out an error in Van Biema's description. He says that the man at the lectern is reading "a treatment of the Virgin Mary from one of the Bible's apocryphal books." Unfortunately, there is no such book in the biblical apocrypha. The biblical apocrypha is a collection of Jewish writings that is included in Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Bibles as "deuterocanonical books," meaning "of secondary canonical status." Protestants regard these books as historical and inspirational writings, but not as God's Word. If you were to read every single document, you'd find absolutely nothing about the Virgin Mary.

Van Biema confuses the biblical apocrypha with what some scholars call "the New Testament Apocrypha," though these books were never included in the canonical New Testament. One of these books, written in the latter half of the second century A.D., is called "The Infancy Gospel of James" or "The Protoevangelium of James" ("the initial gospel of James"). This "gospel" does tell the story of Jesus's birth, but it spends much more time on the miraculous birth and early life of Mary, his mother. In this tale, Mary is rather like the biblical Samuel, born by God's help to aging parents and raised in the Jerusalem temple. When she was twelve years old she was betrothed to Joseph. From there on the story is much like the biblical nativity narratives, though with additional information, like Jesus's birth in a cave. (You can read "The Infancy Gospel of James" online.)

I think Van Biema's description of Marian veneration in El Amor de Dios church actually contains the seeds of its own destruction. Two men read passages honoring Mary. Okay, fine. Do you see anything wrong with this picture? I do. There's no connection to the Bible here. One of the defining characteristics of true Protestantism – our commitment to the authority of Scripture – is decidedly absent from this description of worship in El Amor de Dios. What do we find in its place? Readings from a non-canonical "gospel" and a "dog-eared notebook." Frankly, I don't see the seeds of Protestant Marianism here, or any compelling evidence of a "pro-Marian tipping point." What I see is a novel exception to the Protestant rule, a good-hearted but, for Protestants, theologically-inadvisable flirtation with Marian veneration.

Now if what happened at El Amor de Dios were based on canonical Scripture, then we'd have a completely different situation. This thought raises the question of what we can know about the Virgin Mary from the Bible, and to this topic I'll turn in my next post.

The Virgin Mary in the Bible: A Brief Overview

Part 5 of the series: "The Protestant Mary"

Posted at 10:30 p.m. on Sunday, March 20, 2005

In David Van Biema's recent article in TIME magazine entitled "Hail, Mary," he comments that "a growing number of Christian thinkers . . . have concluded that their various traditions have shortchanged [Mary] in the very arena in which Protestantism most prides itself: the careful and full reading of Scripture."

So, then, what does a careful and full reading of Scripture teach us about Mary? I propose to answer this question with an overview of the biblical material. I have examined every passage of the Bible that mentions (or may refer to) Mary and summarized what this passage teaches. I've put this raw data in an appendix to this series for my "Sergeant Joe Friday readers" who want, "Just the facts, ma'am." (Actually, it's an urban legend that Sgt. Friday said this.) For the rest of you, in this post I've summarized the biblical material under basic headings that describe different aspects of Mary as pictured in Scripture.

Different Biblical Pictures of Mary

Mary of Prophecy. Christians see Mary in three Old Testament passages. Two are obvious prophecies. The first is a little more obscure. After the man and woman sin in Genesis 3, God promised that the "seed" of the woman will "strike the head" of the serpent. If the seed in Christ, then the woman is, in a sense, Mary. Isaiah 7:14 refers to a virgin or young woman (same Hebrew word) who bears a child named Immanuel. Micah 5:2-5 refers to a woman who gives birth to a messianic ruler. |

|

|

| Today is Palm Sunday, the day when Christians remember the triumphal entry of Jesus into Jerusalem. These pictures are of the processional of children in our worship service today. I thought you'd enjoy them. |

|

Mary the Birth Mother of the Messiah, the Son of God. Mary's greatest significance in Scripture is as the one who gives birth to Jesus, the Messiah and Son of God. Thus it makes sense that she appears most of all in the gospel stories of the nativity. Moreover, it is as the birth mother of the Son of God that Mary derives her timeless value. The virgin birth alone wouldn't have made her all that special if she had simply given birth to some ordinary human being. But she gave birth to one who was not merely human. In the terms of later theology, the baby in her womb was "fully God and fully human." Thus by the fifth-century A.D. Mary was recognized as "the mother of God" (theotokos).

Mary the Virgin. The second most important thing about Mary's motherhood is that it didn't begin in the ordinary way. Though she had not had sexual intercourse with a man, she conceived a child through the miraculous intervention of the Holy Spirit (Luke 1:33-38). The Bible itself doesn't explain the physiological process or even the theological significance of the virginal conception. That was left to theologians, who are still arguing about it today. Matthew explains that Mary did not have sexual relations with Joseph while she was pregnant with Jesus (Matt 1:25). The text seems to imply that after his birth she engaged in normal sexual intimacy with Joseph, though Catholic and Eastern Orthodox interpreters dispute this, of course. Moreover, the gospels attest to Jesus having brothers, with the implication that Mary was their mother (Matt 13:55). Other interpreters hold that these brothers were actually half-brothers, the children of Joseph and a first wife. There is no biblical support for this view. So, apart from post-biblical church tradition, there is no biblical evidence for Mary's remaining a virgin. In fact the obvious (but not only) reading of the text points in the other direction.

Mary the Favored, Blessed One. The angel who came to announce to Mary that she was going to give birth to a son addressed her as "the favored one" (Luke 1:28; Greek, kecharitomene, "graced one") adding later that she has "found favor" (Luke 1:30; Greek, charis, "grace") with God. She is also referred to by her relative Elizabeth as "blessed among women" (Luke 1:42; eulogemene). There is no question that Mary has been singled out by God for a uniquely great honor, the honor of bearing the Son of God. Scripture doesn't explain why she received this blessing, though from the text of Luke we learn that she has exemplary faith, that she has outstanding biblical theology (from the Magnificat, Luke 1:46-55), and that she has prophetic gifts (from the Magnificat).

Mary the Faithful Servant of God. When told that she would conceive by the Holy Spirit and bear a son, Mary responded with exemplary faith: "Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word" (Luke 1:38). Later she is referred to as one who believed "that there would be a fulfillment of what was spoken to her by the Lord" (Luke 1:45). Thus she exemplifies full submission to God and, as Protestants are happy to emphasize, genuine faith.

Mary the Mother of Jesus. The New Testament has very little to say about Mary's actual mothering of Jesus throughout the years of his life. We are left to fill in most of these blanks with historical analogies and imagination (such as Mel Gibson does in a few flashback scenes in The Passion of the Christ). The gospels do relate a few stories of Mary's interaction with Jesus as his mother, and these are quite surprising.

Mary is perplexed and anxious when Jesus disappears on the family's trip from Jerusalem to Nazareth. Then she doesn't understand Jesus's explanation of his behavior (Luke 2:41-51).

Mary motivates Jesus to turn water into wine, his first miracle in John. But his response to her seems curious, even disrespectful, though he does the miracle (John 2:1-11).

Mary comes, along with her other children, to speak with Jesus during his ministry. But he appears to diminish her significanceas his natural mother by referring to all who do God's will as his "brother and sister and mother" (Mark 3:31-35 and pars). Of course in Luke 1 Mary is a paradigm for one who does God's will.

Mary is with Jesus at the cross, though we learn nothing about her experience other than as the recipient of Jesus's making her the "mother" of the beloved disciple (John 19:25-27). Some theologians have read a great deal into this text, but seeing Mary as the mother of the church is adding more than the text itself provides.

Mary the Suffering Mother. Since John places Mary at the cross of Jesus, it's safe to assume that her suffering was unbelievably horrible. But the New Testament doesn't supply any description of her pain or behavior. There was a telling prophecy of Simeon, however, when Jesus was a baby. He predicted of Mary that "a sword will pierce your own soul too" (Luke 2:35).

Mary the Disciple of Jesus. Mary was among those who follow Jesus, and she was with him until the end. Like the other disciples, she seemed to be confused by Jesus's actions at times. After the resurrection, she remained with the disciples as they prayed (Acts 1:14), probably being present for the Pentecostal outpouring of the Holy Spirit. Mary is not mentioned after Pentecost, except in one theological statement in Galatians 4 and, perhaps, in Revelation 12.

Tomorrow I'll wrap up this look at the biblical Mary with some general observations. I'll also try to address some of the issues upon which Catholics and Protestants disagree.

The Virgin Mary in the Bible: Some Personal Reflections (Section A)

Part 6 of the series: "The Protestant Mary"

Posted at 9:30 p.m. on Monday, March 21, 2005

This post follows on the heels of yesterday's, in which I laid out in detail the different ways Mary is pictured in Scripture. (If you didn't read that post, you may want to scan it before beginning this one.) I'm going to begin with some personal reflections today, and finish up these reflections tomorrow. From there I'll talk about what I believe are the "real stories" behind Van Biema's article, stories that he didn't explore.

Without a doubt, Mary is unique among all woman, indeed, all human beings, as the one who gave birth to Jesus. The fact of Mary's uniqueness – at least it seems to me a fact – has often been overlooked by Protestants. I expect that this once reflected anti-Catholic attitudes and convictions. But in recent years I think it's more of an oversight than an intentional downplaying of Mary. Those who see some sort of anti-Mary conspiracy among Protestants are overplaying their hand, I think.

For example, in his TIME article, David Van Biema writes,

Over time, Protestant anathemas against Mary lovers gave way to a kind of sullen neglect of the Virgin. That was more pronounced among Presbyterians, some Baptists and others with a strong Calvinist tradition. (The Presbyterian Church U.S.A.'s 1991 Brief Statement of Faith praised the prophets, the Apostles and the Hebrew matriarch Sarah but omitted Mary.)

Van Biema is basically right to use my denomination's Brief Statement of Faith as an example of not including Mary, though this Statement didn't praise "the prophets, the Apostles and the Hebrew matriarch Sarah" so much as celebrate God's work through them. This is quite a significant difference in such a basic statement, where the triune God alone is praised. Frankly, I'd be surprised if those who neglected to mention Mary when they composed this Brief Statement were "sullen" in doing so. And, to be honest, until Van Biema mentioned the omission of Mary from this document, the thought had never occurred to me. Once again, I think "benign" is a better adjective than "sullen" to describe Protestant neglect of Mary, including my own.

Here is an astounding truth: Mary carried in her womb the divine Son of God. She was the physical source of his human nature. This is truly amazing. What happened within Mary is one of, perhaps even the greatest mystery of all time and history: the Word of God became flesh. (The death of the Son of God for us sinners is a mystery equal, maybe even greater than his Incarnation.) Thus Mary has been given a leading role in the drama of human history. As she said in the Magnificat, indeed "all generations will call me blessed." There is strong biblical support for singling out Mary as profoundly blessed, even the most blessed of all people. Nevertheless, in saying this we must remember that "blessed" speaks of God's gracious action more than the worthiness of the individual.

I do not doubt, however, that Mary was an extraordinary person, a woman of incredible faith and theological understanding. We get a glimpse of that faith in her response to the angel: "Here I am, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word" (Luke 1:38). This is the sort of faith and commitment that all of us should emulate. Moreover, Mary's hymn in Luke 1, called the Magnificat because of its first Latin word (magnificat = "magnifies"), is an extraordinary composition, reflecting both deep biblical insight and inspiration by the Holy Spirit. The biblical evidence doesn't suggest, in my opinion, the conclusion that Mary was a Prophet (with a capital 'P'). But it certainly places her squarely in the prophetic tradition.

We should remember that the emphasis of the New Testament is not upon Mary's worthiness to be the mother of Jesus, but rather upon God's grace in choosing her. The angel reveals that she has been the recipient of divine favor, using Greek language we often translate as "grace." I'm not denying the likelihood of Mary's exceptional faithfulness to God and purity of heart. My point is that this is not underlined in Scripture. The biblical accounts focus on God and his grace, and on Mary's laudable response to God's initiative. |

|

|

Newsweek

on

Jesus:

A Quick Summary |

|

| I knew it was going to happen. After Newsweek had done a cover story on the nativity of Jesus just before last Christmas, I expected the magazine to double-up its efforts by doing a story on Easter. And I was right. It was just as I expected. Well, sort of.

You see, I also expected that Newsweek's approach would be similar to its Christmas angle, relying heavily on skeptical biblical scholars to raise doubts about the historicity of the gospel accounts of Jesus's death and resurrection. I was gearing up for the need to do another critical series on the cover story of a national magazine, similar to my series on the nativity article. And when I saw that Jon Meacham, the writer who had done Newsweek's nativity story, was once again writing on Jesus, I gritted my teeth and girded up my loins to do intellectual battle.

And then I read Meacham's article. Several things struck me on my first reading. First, Meacham asked the right questions. He'd done his historical homework and it showed. Second, though maintaining a scholar's critical distance from the historical material he's examining, Meacham seemed more willing to treat the gospel accounts as if they were historically reliable rather than pious fictions. Third, his use of scholars was balanced and wise. Though he quoted from critical biblical scholars, he also included a quotation from Dr. R. Albert Mohler Jr., president of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, and a well-known theological conservative. Twice in his story Meacham quoted from N.T. Wright, whose critical writing on Jesus is extremely balanced and, in my opinion, second to none in the world. Gone were the agenda-driven scholars of the Jesus Seminar. They were replaced by some of the finest scholars in the world (not only Wright, but others like Jaroslav Pelikan from Yale).

Although I could quibble with elements of the Newsweek article (which isn't saying much, because I could also quibble with things I've written myself), all in all I found the piece to be exceptionally fair. And fair is all I want. I don't expect Newsweek's cover story to sound like an Easter sermon. And I don't need it to represent only the views of evangelical scholars. Rather, I'd hope for a centrist, sober, respectful examination of the evidence. And this is what Meacham provides. Yet, beyond balance, at times his discussion is almost poetic. This article is not only well written from an academic point of view, but from a literary perspective as well.

So, rather than writing a long critical commentary, I simply want to thank Jon Meacham and Newsweek for a piece of solid journalism. |

I find it fascinating how freely the gospels portray the awkwardness of Mary's relationship with Jesus. This, by the way, would be a strong point in favor the historicity of the gospel accounts, since they certainly weren't "cleaned up" to make Mary and Jesus look better. The predominant picture of the post-partum relationship between Jesus and Mary is not one of ideal familial love or discipleship. The boy Jesus perplexes Mary by remaining in the temple and confuses her with his response. As a man he speaks oddly to her when she asks him to deliver more wine to the wedding reception. And he diminishes her importance as his natural mother by referring to any woman who does God's will as his "mother." Of course Mary, as one who does God's will, is then both Jesus's mother and his "mother." But Scripture doesn't make this point directly.

As many have pointed out, Mary is with Jesus in the key moments of his earthly life: conception, birth, moments of earthly ministry, and death. Surprisingly, she is not mentioned as a resurrection witness, though odds are that she did indeed see Jesus alive after death. She was with the disciples after the resurrection, and presumably participated in the Pentecostal outpouring of the Spirit. Thus it's correct to say that Mary was a disciple of Jesus, even his first disciple, after a fashion. |

|

| |

This fresco of the Annunciation (the angel's announcement to Mary) was painted by Fra Angelico in 1440-41. It is in the Convento di San Marco, in Florence, Italy. The man on the left, behind the angel, is St. Peter of Verona. (It pains me to say that last summer I was within a hundred yards of this fresco, but did not see it. Sigh!)

|

Tomorrow I'll continue these reflections on Mary in the Bible, considering her presence at the Crucifixion and the practice of "praying" to Mary.

The Virgin Mary in the Bible: Some Personal Reflections (Section B)

Part 7 of the series: "The Protestant Mary"

Posted at 10:30 p.m. on Tuesday, March 22, 2005

Today's post is a continuation of yesterday's personal reflections on the Virgin Mary.

It seems odd to me that the New Testament says so little about Mary's involvement in Jesus's death, especially given how much this comes to mean in later Roman Catholic tradition (for example: The Stations of the Cross, The Passion of the Christ). The Gospel of John places Mary at the cross (John 19:25-27), but says nothing else about her experience there (besides what Jesus says about her becoming the "mother" of the beloved disciple). Oddly, the other three Gospels do not mention Mary's presence at the cross, though I don't doubt the historicity of John's account. Its minimalism actually speaks to its accuracy in my view, since you'd expect that a fictional account would have added much more embellishment.

Given how little is said in the New Testament about Mary at the cross, I find Van Biema's comment about all of this to be rather peculiar. He writes, "The most striking omission [of Mary], at least from Protestant sermons, is a recognition of the import of her role at the Cross." This doesn't impress me as a striking omission at all. Roman Catholic tradition makes a great deal of Mary's presence throughout Jesus's crucifixion, adding all sorts of extra-biblical material to the gospel accounts. Moreover, in the Catholic tradition, Jesus's words to Mary and the beloved disciple are seen by some as establishing her as the mother of all believers. Furthermore, her suffering as the natural mother of Jesus, not to mention his devoted disciple, becomes paradigmatic of all human suffering. But a Protestant preacher isn't going to get this from of the New Testament sources, which is where we Protestant preachers go for our material. The "omission" of the "import" of Mary's role at the cross is "most striking" only if you look at it through Roman Catholic eyes. Then, I'll agree, it is remarkable to see how something so important in Roman Catholic piety appears to mean so little to Protestants. But this should come as no surprise to anyone, given the Protestant reliance on Scripture and the Catholic reliance on Scripture plus later tradition.

So much of what we'd like to know about Mary is not revealed to us in the Bible. Church tradition fills in some of the blanks, and this may reflect what really happened. But we who don't have an infallible Pope can't be sure about so much of what intrigues us. I'm not speaking facetiously when I say this about the Pope, by the way. Those who believe that the Pope has spoken infallibly concerning Mary have more to go on than we Protestants. We who base our theology upon Scripture alone will not be able to go to the lengths of Marian veneration that are common among some Roman Catholics. Many aspects of this veneration are not objectionable to us, however, because we also recognize and "hail" blessed and honorable disciples. We have our Christian heroes and heroines, and surely Mary should be prominent among them, if not preeminent. But when veneration of the human Mary leads to praying to her as if she were a divine being or exalting her as "co-redeemer" with Christ, then we who base our theology on Scripture alone realize we can't go there.

I should mention that many Catholics distinguish between praying to Mary and praying to God. Years ago a brilliant Catholic friend of mine named Mike explained that, for him, "praying" to Mary is exactly like sharing a prayer request with a good friend. It's not praying to her as if she had divine power and wisdom. Rather, it's asking her to pray, just like Protestants might ask a wise Christian friend to intercede on their behalf. I challenged Mike by saying something like, "Why bother? If you can speak straight to God, why mess around with Mary?" His response was, "Don't you like knowing that a mature believer is praying for you? That's how I feel about Mary." I could see his point, though I haven't joined him in his Marian piety because I'm not sure Mary is in a place to hear my prayer requests or to intercede on my behalf. |

|

| |

A painting by Vecellio Tiziano of the "Assumption of the Virgin" (1516-18). For centuries Catholics have believed that, after her death, Mary was taken up into heaven body and soul. In 1950 Pope Pius XII declared infallibly that the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin was Catholic dogma.

|

Though the Bible reveals Mary to be unique among all human beings, she remains a blessed person whose life points to God, the God who, in the mystery of his will, became flesh in her womb. Thus I think it's unlikely that growing Protestant interest in Mary will lead, as David Van Biema believes, to substantial changes in Protestant worship or piety. The TIME article cites with apparent affirmation the idea of Lutheran theologian Carl Braaten, that "Marianism" will eventually impact Protestant denominational worship. While this may be true to some extent among Protestants who do not have a high view of biblical authority, the rest of us won't have much place for Mary in our worship, other than as an outstanding reminder of God's grace (John Buchanan's sermon), a preeminent example of faith in God, and, of course, the one whom we "drag out" for our Christmas pageants. Even though Mary might indeed be the most blessed and special person in all of history, Christian worship never focuses – or should never focus – on any person, no matter how wonderful, but on God, the source of all wonder, including the marvel of the incarnation of the Word of God in the womb of Mary, the blessed virgin.

I have experienced this sort of focus in worship, not only in Protestant settings, but also in Roman Catholic settings as well. Allow me to share an ironic illustration.

|

When I was in graduate school, I found it increasingly difficult to do my daily devotions in my apartment. I was restless and distracted, always reminded of how much unfinished studying I had to do. So I resolved to find a church in which I might have time alone for prayer and Bible reading. Of course the Protestant churches in my Cambridge, Massachusetts neighborhood weren't open during the week, but I found a Roman Catholic church only a few blocks away that opened each day for noon mass. I decided to join the next day's mass at this church, which, ironically enough, was called St. Mary's of the Annunciation. |

St. Mary's of the Annunciation in Cambridge, Massachusetts. |

|

I felt very awkward at my first mass because I was so unfamiliar with the liturgy. Yet I sensed a genuine worshipfulness in the small congregation. I sat way in the back of the humble chapel at St. Mary's, trying to appear inconspicuous, which was a little hard given that I was the only worshiper under 60, and that I was the only one who did not come forward to receive communion. Nevertheless, I felt welcomed, and found the quietness of the chapel conducive to prayer. After the mass I was free to remain for as long as I wished to pray and read Scripture.

For the next several months I attended noon mass a couple of times a week. Each time I heard the priest offer a short homily on one of the day's biblical passages. And each time I marveled at how utterly Christ-centered and evangelical his messages were. If I were to preach one of his sermons today in my Presbyterian church, nobody would guess that it was once delivered by a Roman Catholic priest.

I'll never forget the "punch line" of his All Saints' Day message. Here is my paraphrase: |

|

| |

A painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe from the inside of St. Mary's church. |

Yes, we revere the saints because of their exemplary lives. We hold them up to be emulated. We even talk to them to ask for their help. And, at St. Mary's, of course we love the Blessed Virgin. But let us always remember that we are first and foremost a people devoted to Jesus Christ, who alone is our Savior. All the saints, and even his exalted mother, point us to Jesus Christ. So on this All Saints' Day, let's follow their example by focusing, not on them, but on Christ himself.

I'm quite sure this priest believed more about Mary than I did, and, for that matter, more about the nature of the church than I did, and more about the authority of church tradition than I did. But there was no question in my mind that we shared the same basic faith in God who has made himself know through Jesus Christ. Thus, much to my surprise, I found more common ground with this priest than I expected, even when it came to the way he talked about Mary in a church named in her honor.

I don't have sufficient experience of Roman Catholic worship, nor sufficient knowledge of contemporary Roman Catholic theology, to know if my experience at St. Mary's of the Annunciation was representative of Catholic piety and thought today. But what I do know is that what I once perceived to be a vast gulf between Protestantism and Roman Catholicism turned out, in my experience, to be a modest gap that I found surprisingly easy to cross.

This experience points to a larger story I want to pursue tomorrow. It's one of the "real stories" that David Van Biema missed in his TIME article, and that I believe deserves to be told.

The Protestant Mary: What's the Real Story? (Section A)

Part 8 of the series: "The Protestant Mary"

Posted at 9:30 p.m. on Wednesday, March 23, 2005

Early in this series I said that I agreed with David Van Biema's basic observation that there is growing openness among Protestants to take Mary seriously. The evidence he lays out in his TIME cover story supports this claim, as does my own experience as a Protestant (47 years) and a Presbyterian pastor (20 years). But, as I've made clear throughout the series, I think Van Biema's assertion of a "pro-Marian tipping point" among Protestants, one that will lead to inclusion of Mary in Protestant worship and prayer, is not supported by the evidence. In proposing this thesis it seems that Van Biema has been influenced too much by the opinions of a few Protestant scholars while overlooking the actual experience and perspective of the vast majority of Protestants.

Yet I do believe there's more to the "Protestant Mary" story than merely a greater openness among Protestants to think and talk about Mary. Beginning with today's post I'll try to sketch some of the features of this "real story." (Please note the word "sketch." Remember that I'm a blogger who has one, maybe two hours a day to work on this stuff. I don't have the time and resources of a writer for TIME. So I can't supply the texture and detail I wish I could provide.)

So what is the bigger story behind the Protestant Mary? Let me put it this way: The greater openness of Protestants to Mary is simply one sign of the greater openness among Protestants to Roman Catholicism in general. As I noted at the close of my last post, what many Protestants, including me, once perceived to be a "vast gulf between Protestantism and Roman Catholicism" has turned out to be "a modest gap" that we can easily cross. Or to put it differently, we Protestants sense a deeper unity with our Catholic brothers and sisters than we once felt, and we recognize more clearly than we once did the extent to which we share a common faith in the triune God who has been revealed most plainly in Jesus Christ, the Son of God and our Savior. Sure, there are still lots of differences in belief and practice between Protestants and Catholics, but these just don't seem to be as important as they once seemed.

There was a time, not all that long ago, actually, when Catholics and Protestants deeply mistrusted each other, or even worse. We doubted each other's salvation and vociferously denied each other's orthodoxy. This division often led to painful choices and rejections. One of my dissertation advisors, for example, was a Roman Catholic priest. He once shared with me that his family was half Catholic (by his mother) and half Presbyterian (by his father). When he decided to become a Jesuit priest, the Presbyterian side of his family disowned him and had no more to do with him. This painful experience happened around 1960.

At about this same time, during the 1960 Presidential election John Kennedy's Catholicism was a major issue, with many Protestants opposing him on religious grounds, fearing that his allegiance to Catholicism in general and the Pope in particular would hurt our country.

Much has happened since then. On the Catholic side, the Second Vatican Council (known as Vatican II) led to a greater openness from Catholics toward Protestants. This groundbreaking perspective can be found, for example, in the Vatican II document known as Lumen Gentium (light of the nations). Though reaffirming that the one church of Jesus Christ "subsists in the Catholic Church, which is governed by the successor of Peter and by the Bishops," the Vatican counsel went on to note that "many elements of sanctification and of truth are found outside of its visible structure. These elements, as gifts belonging to the Church of Christ, are forces impelling toward catholic unity." In other words, the Roman Catholic church officially acknowledged that "many elements of sanctification and of truth" can be found in Protestantism.

Scholars and church leaders might explain today's greater unity between Catholics and Protestants as a result of organized ecumenical efforts, and these may well have had some impact. But I'm convinced that the mending of the breach between these two major branches of Christianity comes from several other sources as well. Some of these have occurred to me through my own reflection and study; others have been mentioned by my readers, either in my Guestbook or in e-mail correspondence. I'm going to begin to summarize these factors today.

Some Reasons for the Mending of the Divide Between Catholics and Protestants in America

Kennedy's Patriotism.

Americans did in fact elect John F. Kennedy as President in 1960, and, though his tenure was a short one, it was obvious that his Catholicism did not keep him from putting America's interests first in his presidency. John F. Kennedy didn't sell out the U.S to the Pope. Even though Kennedy had a papal audience while he was President, his actions as President quelled Protestant fears and increased toleration for Catholics in general. |

|

|

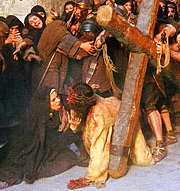

I saw The Passion Recut today. As you may know, it's a slightly-less violent version of The Passion of the Christ, which Mel Gibson made to appeal to folks who would be put off the extreme violence of the original film. The good news is that The Passion Recut is, in my opinion, a even better film than the original – and I was a big supporter of the first movie. By subtracting some of the most graphic violence and adding a few scenes that emphasize more relational elements, for example, the response of the crowd (including Jesus's mother Mary) to his flogging, The Passion Recut grips the heart without some of the repulsiveness of the original film. Moreover, taking away some of the flogging scene actually gives more attention to the crucifixion scene, which, in my opinion, is an improvement..

I had heard that Mel Gibson was hoping for a PG-13 rating for The Passion Recut. Frankly, this rather surprises me, because I would still give the film an R+ rating for extreme violence and gore. This isn't a criticism, mind you, because you just can't make a realistic movie about Christ's death that is anything less than terribly violent.

On The Passion of the Christ trivia side of things, I heard something in this film that I missed the first two times. When Pilate first begins to question Jesus, Pilate speaks to him in Aramaic. Jesus answer in Latin, which seems to make an impression on Pilate. From then on they discourse in Latin. I wonder what Gibson thinks of this. (In fact I think it's unlikely that they spoke together in either Aramaic or Latin. If they did not have an interpreter, I'd wager that Jesus and Pilate spoke in Greek. If you're interested in this argument, you can check out my series on the language(s) of Jesus.)

Finally, given this blogging series, I was exceptionally attentive to the portrayal of Mary in The Passion of the Christ. Once again I found this to be a gripping and believable presentation. Mary is an exceptionally genuine, human character. Her suffering is portrayed as truly horrible, but it's not overdone. This time around I was more impressed than before with Mary's incredible strength and her implicit faith in necessity and purposefulness of her son's death.

Once again I was deeply moved by the scene in which Mary runs to comfort Jesus after he falls under the weight of the cross, much as she once did when he was a boy. Her reaction made such sense to me as a parent. Yet what touched me was not only Mary's reaching out to Jesus, but his response to her love. Turning to face her, he says, "Mother, look, I am making all things new!" And then with renewed strength he stands to continue his long walk to his death. The irony in this scene is thick, of course. But it's also a marvelous portrayal of how Mary and her love don't turn attention to her, but rather they highlight and support the ministry of Jesus. |

The Charismatic Movement.

The so-called "Charismatic Movement" led to greater unity among certain groups of Christians, a unity that crossed "party lines," as it were. In the 1960s a movement (participants would see it as a movement of the Holy Spirit) began sweeping through several denominations of the Christian church. This Charismatic Movement emphasized more direct experience of God through the "baptism of the Holy Spirit."

| Charismatic worship featured emotional singing and praying, a precursor to today's contemporary Christian music in worship. Charismatic piety often emphasized speaking in tongues as a part of private prayer and corporate worship. In many settings Charismatic Protestants and Charismatic Catholics discovered a profound unity in faith and experience, a concord that was sometimes increased by the rejection they experienced in their own churches. During this time Catholic Charismatics and Protestant Charismatics often experienced greater unity with each other than with others from their own denominations. |

|

| |

A typical view of a Charismatic worship service. |

|

Mother Teresa of Calcutta.

Mother Teresa was beloved by Christians across the denominational spectrum. In the last two decades of the twentieth century, no Christian in the world was held in higher esteem than Mother Teresa, the tiny sister from Calcutta who led a movement to care for the poor and dying. When she won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1979, this was a moment for all Christians to celebrate. Mother Teresa became the compassionate, humble, faithful "face" of Christianity in general, not just Roman Catholic Christianity.

Tomorrow I'll look further at reasons why the breach between Catholics and Protestants is being mended. |

The Protestant Mary: What's the "Real" Story? (Section B)

Part 9 of the series: "The Protestant Mary"

Posted at 9:30 p.m. on Thursday, March 24, 2005

Yesterday I began to explore what I believe is the "real" story behind greater Protestant openness to the Virgin Mary. Here is that story in a nutshell:

The greater openness of Protestants to Mary is simply one sign of the greater openness among Protestants to Roman Catholicism in general. We Protestants sense a deeper unity with our Catholic brothers and sisters than we once felt, and we recognize more clearly than we once did the extent to which we share a common faith in the triune God who has been revealed most plainly in Jesus Christ, the Son of God and our Savior.

In my past post I began to summarize some of the factors that have contributed to the mending of the breach in Protestant and Catholic relations in addition to the impact of Vatican II. These were:

Kennedy's Patriotism

The Charismatic Movement

Mother Teresa of Calcutta

Today I'll add to this list additional reasons that have helped Protestants be more open to Catholicism in general.

John Michael Talbot's Music

| The number one Catholic recording artist in album sales became popular with many Protestants beginning in the late 70s. John Michael Talbot, who once performed with the secular folk-rock group, Mason Proffit, became a Christian in the context of conservative evangelicalism, but then converted to Roman Catholicism, even becoming a Franciscan monk. Talbot's albums, mostly of quiet worship music, have sold over four million copies, with vast numbers of these purchased by Protestants. In the early 80s, for example, I became a fan of Talbot's, listening for hours to his music. I was unaware, at first, that many of his early lyrics were taken directly from the Catholic Mass. Thus Talbot built a bridge into many Protestant communities, including quite conservative evangelical ones. |

|

| |

To listen to a clip of John Michael Talbot's music, click here (.mov file 254 K). The lyrics are from the "Gloria" in the Catholic Mass: "Lamb of God, you take away the sin of the word, have mercy on us." To order the album from which this song comes, click here. |

Henri Nouwen's Writings

|

Nouwen's writings continue to touch the hearts and stretch the minds of Protestants and Catholics. Over two million books written by the Catholic priest Henri Nouwen have been sold, according to the website of the Henri Nouwen society. I became aware of the writings of this Dutch priest in the early 80's. Like thousands of Protestants, especially church leaders, I found his hunger for God to be engaging and contagious. Nouwen's Christian spirituality transcended his Catholic expressions, and his love for people built bridges across the Christian community. (Twice I had the opportunity to meet with Henri Nouwen, whom I found to be one of the kindest and wisest men I've ever known. One of my earthly treasures is a copy of his book, The Return of the Prodigal Son, which Henri signed and gave to me. His advice to Protestant pastors like me, by the way: "Lead people to Jesus.")

If you're interested in Nouwen's writings, I would recommend his classic The Wounded Healer or The Return of the Prodigal Son. |

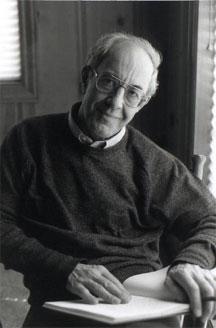

John Paul II's Christ-Centeredness.

The Christ-centered message of Pope John Paul II strengthened the unity between Catholic and Protestant Christians. I'll never forget the rainy evening of October 1, 1979. As a graduate student in religion at Harvard, I was eager to follow the visit of Pope John Paul II to America. It began with a mass across the Charles River in Boston. I headed to a local bar to watch the mass because I didn't own a television. (Yes, this is what was playing at inner city Cambridge bar!) I sat transfixed as I heard a message which, if not coming from a Catholic Pope with a strong Polish accent, could well have been preached in just about any evangelical church in America. In the conclusion of his homily, the Pope exhorted us to "Follow Christ!" Specially addressing married people, the unmarried, young and old, the Pope repeated his call to follow Christ, five times in all. His final line was, "For this I have come to America, and for this I am in Boston this evening: in order to call you to Christ, in order to call all and everyone of you to live in his love, today and always. Amen!" (A transcript of this message is available online, but only in Italian translation.)

Later that evening I was distressed by the news accounts of the Pope's sermon. You would have thought that his entire point was to oppose abortion. Admittedly, a small bit of the homily made a pro-life statement. But this was a minor theme in a Christ-centered evangelistic message. The evening of October 1, 1979 was the first time I realized that the secular media has its own agenda when reporting on religious matters, and has a difficult time comprehending what Christians actually think, feel, and do. I didn't believe that the reporters were intentionally twisting the story. They were simply hearing and reporting things in light of their expectations and convictions about what was important.

Pope John Paul II's evangelical passion for Christ has done much to bring Catholics and Protestants together. I must mention, however, that his passionate devotion to the Virgin Mary has been a bit of a stumbling block. On the one hand, such an emphasis makes it impossible for Protestants to give a blanket "Amen!" to the Pope. Yet, on the other hand, it also makes it hard for us to dismiss Marian piety as something for uneducated or theologically naïve folk. Few people in the world can match Karol Wojtyla's intellect. He's not easily dismissed, which makes his devotion to Mary both intriguing and troubling for those of us who don't share it. |

|

| |

Given the Pope's poor health today, it's easy to forget just how vigorous and charistmatic he was 25 years ago.

|

Tomorrow I'll continue to examine factors that have led to a greater sense of unity between Protestants and Catholics.

The Protestant Mary: What's the "Real" Story? (Section C)

Part 10 of the series: "The Protestant Mary"

Posted at 9:30 p.m. on Friday, March 25, 2005

In the last couple of days I have begun to lay out what I believe is the "real" story behind greater Protestant openness to the Virgin Mary. Here is that story in a nutshell:

The greater openness of Protestants to Mary is simply one sign of the greater openness among Protestants to Roman Catholicism in general. We Protestants sense a deeper unity with our Catholic brothers and sisters than we once felt, and we recognize more clearly than we once did the extent to which we share a common faith in the triune God who has been revealed most plainly in Jesus Christ, the Son of God and our Savior.

In my past two posts I started to summarize some of the factors that have contributed to the mending of the breach in Protestant and Catholic relations in addition to the impact of Vatican II. These were:

Kennedy's Patriotism

The Charismatic Movement

Mother Teresa of Calcutta

John Michael Talbot's Music

Henri Nouwen's Writings

John Paul II's Christ-Centeredness

Today I'll add to four other factors to this list of reasons why Protestants have become more open to Catholicism.

Protestant Rediscovery of Catholic Spirituality.

In the last twenty years Protestant Christians have rediscovered spiritual disciplines that were associated with Roman Catholic spirituality (though many are broadly shared among Christians of various traditions). Silence, meditative reading of Scripture (lectio divina), spiritual retreats, spiritual direction, and other disciplines have enriched the spirituality of millions of Protestants. The writings of Henri Nouwen and Richard Foster (The Celebration of Discipline) contributed to the popularity of such traditional forms of discipleship.

Catholic retreat centers, unlike the typical Protestant variety, tend to have minimal recreational options and maximal opportunities for quiet, worship, and prayer. They are also well-equipped for individual retreats, rather than just group events. |

|

| |

The red-roofed buildings in the center of this picture are the Serra Retreat Center, a Catholic facility in Malibu, California, where I have spent many retreats, both in private and in groups (of Protestants). Ironically, this center is literally a stone's throw from Mel Gibson's house.

|

Ancient-Future Worship and Perspective

In the last twenty years many Protestant, and even conservative evangelical and/or charismatic churches, have looked to the ancient church for worship resources. We've adopted practices that we once would have identified as "Roman Catholic" – passing of the peace, Ash Wednesday services, the use of visual images in worship, etc. This has given Protestants a greater appreciation for Catholic traditions and made it easier for us to "cross over" in our worship.

|

Protestant author Robert Webber coined the phrase "ancient-future" to describe the renewal of Protestant worship that draws from the past while at the same time making future-oriented innovations. Webber has authored a series of books with this theme, looking at ancient-future evangelism, faith, time, etc. Webber, who also has a regular "Ancient-Future Worship" column in Worship Leader magazine, is possibly the most influential Protestant in America when it comes to worship, since he has had a vast impact in diverse streams of Protestantism through his writings and conferences. He edited The Complete Library of Christian Worship, which I consider to be the greatest resource for worship leaders (apart from Scripture itself!). This series of eight volumes draws upon various traditions of Christian worship, including Roman Catholic, though the Library is intended primarily for Protestant readers. (Remember, when you use pre-Reformation worship materials, the Catholic/Protestant distinction makes little sense.) |

The "ancient-future" Robert Webber

|

|

The Changing Polarizations of Our World.

Fifty years ago the world was divided between Eastern Bloc communism and Western democracy. In our everyday experience, however, we Americans didn't run into Communists. Just about everybody we knew was more or less Christian. Within this "more or less Christian world" we made distinctions among ourselves. It mattered quite a bit what kind of Christian you were: Methodist, Baptist, Presbyterian, or Catholic. The differences between a Presbyterian and a Catholic loomed large. Many Protestants, in fact, doubted that Catholics were real Christians, and many Catholics returned the favor. I remember asking my freshman roommate in college if he was a Christian. "I'm not a Christian," he answered. "I am Catholic." This reflected the kind of polarization he had experienced in the South, where "Christian" meant "Baptist" or "Methodist" but not "Roman Catholic."