A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

How Can We Know Anything About the Real Jesus?

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts February 2004 (rev. 3/3/04)

Copyright © 2004 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com. Thank you.

My Various Writings on Jesus

The Birth of Jesus: Hype or History?

Was Jesus Divine? The Early Christian Understanding

Why Did Jesus Have to Die?

Was Jesus Married? A Careful Look at the Real Evidence

What Was the Message of Jesus?

How Can We Know Anything about the Real Jesus?

What Languages Did Jesus Speak and Why Does It Matter?

Recovering the Scandal of the Cross?

The Passion of the Christ: An In-Depth Review

Book -- Jesus Revealed: Know Him Better to Love Him Better

Table of Contents

Part 1 : Introduction

As we get closer to the release of The Passion of the Christ, more and more people will be talking and writing about Jesus. Opinions will differ, sometimes widely, about who Jesus was, what he did, and how all of this matters today. No doubt you'll run into claims that we really can't know very much about the real Jesus at all because our historical sources are too unreliable.

In this post and in those to follow I want to give a concise answer to the question: How can we know anything about the real Jesus? I will present a brief overview of the historical sources we have for knowledge of Jesus. As a Christian I believe that the New Testament gospels are divinely inspired and therefore trustworthy sources for knowledge of Jesus. But in this series of posts I want to consider the question of sources, not from the perspective of faith, but from the perspective of historical investigation.

Before I examine the sources, however, I need to make a couple of preliminary comments. First, I'm well aware that the topic I plan to consider in a few posts is one of the most complicated and convoluted in all of scholarship. The question of how we can know the truth about Jesus has spawned a centuries-long debate, and this debate is hardly over in scholarly circles. Nevertheless, I plan to address some of the main issues in a readable, concise, and useful manner. Obviously I'll be summarizing and offering my own conclusions, yet without giving you pages and pages of argument and evidence. (If you're interested in such detail, I'll point you in the right direction.)

Second, in the last two centuries the study of Jesus has been plagued with historical skepticism. It used to be the miracles of Jesus that led scholars to doubt the historical reliability of the gospels. More recently many have argued that the gospel writers have theological agendas, and these somehow get in the way of truthful history. But this begs the question, because if my theology values history, then my having a theological agenda might very well lead me to be a better historian, not a worse one. In a few posts I'll examine one of the "agendas" of a New Testament gospel, showing how this supports rather than undermines the historical reliability of the text.

But before I get to the New Testament gospels, I want first to look at the other ancient sources that tell us something about Jesus. I'll start with Roman sources, followed by Jewish writings, then Christian writings outside of the New Testament, then New Testament writings other than the gospels, and finally I'll consider the gospels themselves. After a brief survey of these materials you'll be able to answer the question: "How can we know anything about the real Jesus?"

I want to conclude with a word about why all of this matters. If we were Gnostics, we wouldn't give two cents for history. What matters to the Gnostic is spiritual revelation and insight. That's it. But Judaism and Christianity are rooted, not merely in ideas or subjective experiences, but in God's action within history. I'm not talking about raw history, of course, but historical events interpreted in light of God's revelation. It's a brute fact that "Christ died." But when St. Paul says that "Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures " (1 Cor 15:3), he is now interpreting an event from a divine point of view. Yet, even though the interpretation matters profoundly, so does the basic event. Thus knowing something about the real Jesus makes a real difference, not only for serious historians, but also for serious Christians.

Part 2 : Roman Sources

In my last post I clarified the purpose of my current mini-series: to answer the question "How can we know anything about the real Jesus?" In this post and the ones that follow I will provide a brief overview of the historical sources from which we derive information about Jesus. Today I'll begin to examine the evidence from earliest Roman writers who mention Jesus.

Ironically, all the three Romans who mentioned Jesus wrote about eighty years after his death - within a year or two of 110 A.D. Two of these writers were historians; one was a Roman governor who penned numerous letters.

A Letter from Pliny to Trajan

The governor was a man named Gaius Pilinius, whom we call Pliny the Younger (to distinguish him from his uncle, Pliny the Elder, a famous naturalist). The younger Pliny served as the Roman governor of Pontus and Bithynia (northern Turkey) from 111-113 A.D. During his tenure he wrote numerous letters, including a letter to the Emperor Trajan asking how he should deal with Christians who were accused of crimes against Rome.

Pliny's letter provides a fascinating glimpse of early Christian belief and behavior, though relatively little information about Jesus himself. Pliny states that Christians will never "curse Christ" and that they meet together each week, during which time they "sing responsively a hymn to Christ as to a god" (Letters, 10.96).

Pliny appears to have no knowledge of Jesus independent of what he has learned from Christians. Nevertheless, he documents that fact that they were becoming a problem in his region, and that they held Jesus in the highest regard, calling him "Christ" and worshipping him as God.

Suetonius: Life of Claudius

Around 110 A.D. the Roman historian Suetonius wrote a history of the Caesars. In his "Life of Claudius" he appears to mention Jesus, though in a peculiar passage. It reads: "Since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, he expelled them from Rome" ( Claudius , 25.4). Suetonius refers to an act of Claudius in 49 A.D. His use of the name "Chrestus" might refer to Christ, though the correct Latin name for Christ would be "Christus." Nevertheless, most scholars believe that Suetonius simply got the vowels confused (or his source did).

This passage shows how the Romans would have viewed Christians in the middle of the first century A.D. - as Jews who were making trouble because of somebody named Christ. Like Pliny, Suetonius appears to have no actual knowledge of Jesus. He may even have imagined Christ himself to be a rabble-rouser in Rome around 49 A.D.

I should note at this point a fact of early Christianity that is often ignored by Christians today: the earliest believers in Jesus were Jewish, and they considered belief in Jesus as the Messiah to be consistent with their Jewish faith and practice. Christianity emerged as a non-Jewish religion toward the end of the first century A.D., but it didn't begin there. This is a good reminder to all Christians of the debt we owe to the Jews.

In addition to the references to Christ in Pliny and Suetonius, there are a couple hints about Jesus in the writings of Lucian of Samosata, Mara bar Serapion, and Julius Africanus, but these are too obscure to explore in this post. There is one relatively meaty passage, however, in the work of the historian Tacitus.

Tacitus: Annals

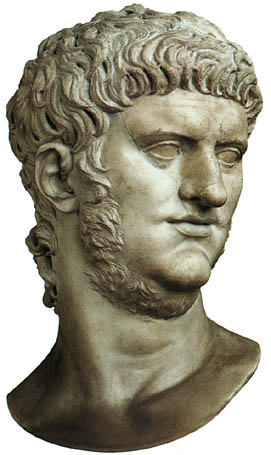

In 109 A.D., Tacitus wrote an extensive history of the first-century Roman Empire. In his discussion of the Emperor Nero, who reigned from 54-68 A.D., Tacitus reports that citizens were blaming Nero for the terrible Roman fire in 64 A.D. He decided to deflect criticism by blaming Christians. Here's Tacitus's description:

|

Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judaea, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular. (Ann. 15.44) |

Bust of Nero |

Apart from Tacitus' fascinating appraisal of Christianity as "a most mischievous superstition," he notes that Christ "suffered the extreme penalty" under Pontius Pilate - an obvious reference to Jesus' crucifixion. This does seem to fix the time of Jesus' death and the ultimate responsibility for that death.

Summing Up the Roman Evidence

There isn't really much Roman evidence to summarize. Jesus is rarely mentioned in Roman writings, though he does show up in a few scattered references. Why isn't Jesus discussed more often in this literature? The answer is simple: because he wasn't known or considered to be very important from the perspective of first- and second-century Roman history and government. He was simply one among many Jewish rabble rousers who had to be put down by the state. The fact that his followers were beginning to cause problems for Rome explains why Jesus was mentioned at all by Pliny, Suetonius, and Tacitus. But from the perspective of a leading Roman living around 110 A.D., Christianity was at most one of those annoying superstitions that disturbed Roman order and deserved to be squashed.

Part 3: Jewish Sources

The Talmud

Jesus is mentioned occasionally in the Jewish Talmud, though often cryptically. Only a few passages appear to mention Jesus directly, and these - no surprise - are negative. For example, in one tractate of the Talmud its says that "Jesus the Nazarene practiced magic and led Israel astray" (b. Sanh. 107b). The Talmudic passages may preserve some genuine historical traditions about Jesus even though they were penned at least three centuries (or more) after his death.

But one Jewish writer in the first-century did mention Jesus in at least one passage, and probably two.

Josephus: Jewish Antiquities

In the early 90's of the first-century A.D., the Jewish historian Josephus wrote several treatises on Jewish history. He wrote to build bridges between Rome and the Jews, to explain why their relationship had been so rocky, and to iron out differences between them.

In one place in his Jewish Antiquities Josephus mentions Jesus indirectly. His focus is on the killing of James, who is identified as "the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ" (Ant. 20.9.1). In this context Josephus has no need to say more about Jesus himself.

The other passage where Josephus appears to mention Jesus is disputed because it comes to us only by way of medieval Christian sources, and these sources appear to have doctored the original text. Josephus is in the process of describing Jewish conditions under Pontius Pilate when we read:

Now there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man; for he was a doer of wonderful works, a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him both many of the Jews and many of the Gentiles. He was [the] Christ. And when Pilate, at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to the cross, those that loved him at the first did not forsake him; for he appeared to them alive again the third day; as the divine prophets had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him. And the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct at this day. (Ant. 18.3.3)

Given what we know about Josephus' beliefs (he was not a Christian), it's unlikely that this passage, in its current form, comes from his own hand. Many scholars believe that Josephus actually wrote about Jesus in this context, though without the obvious Christian touches.

Given uncertainty about the second passage, I do not want to claim too much about Josephus' knowledge of Jesus. He did know that Jesus "was called Christ." And he may well have known that Jesus was crucified under Pilate, but of this we cannot be certain.

Summing Up the Jewish Evidence: The Jewish evidence for Jesus is slight. This isn't surprising, really, because, apart from Josephus, we don't have literature from Jewish historians at this time. Jesus is surely known to the Rabbis cited in the Talmud, but their knowledge of Jesus is not independent of earlier sources. Moreover, given the conflicted relationship between Jews and Christians in the first few centuries A.D., we wouldn't expect them to say much about Jesus.

Part 4: Second-Century Christian Sources

Beginning with this post I want to examine Christian sources for information about Jesus. Admittedly these sources are not neutral with respect to who Jesus was and what he did. But, as we have seen, neither are the Roman and Jewish sources.

Most of the second-century Christian writings, whether orthodox, heterodox (meaning "not orthodox"), or heretical, use the New Testament writings as their primary source for knowledge of Jesus. Thus they provide little more than evidence that the biblical writings were early and well-used. However, some of the non-biblical Christian writings may preserve traditions that were earlier than or distinct from the New Testament writings.

The Letters of Ignatius

Some scholars have argued, for example, that the letters of Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch in Syria, written around A.D. 110, preserve traditions about Jesus that are older than the New Testament gospels themselves. Thus the writings of Ignatius might serve as a witness to early sources of knowledge about Jesus.

What we find in Ignatius, however, confirms what we find in the biblical materials. In one of his letters, for example, Ignatius urges a church: "Be ye deaf therefore, when any man speaketh to you apart from Jesus Christ, who was of the race of David, who was the Son of Mary, who was truly born and ate and drank, was truly persecuted under Pontius Pilate, was truly crucified and died in the sight of those in heaven and those on earth and those under the earth; who moreover was truly raised from the dead" (Ignatius to the Trallians 9:1-2). These basic "facts" about Jesus are found throughout the earlier New Testament writings. Notice how Ignatius goes to great pains to point out that these things really happened. They were not just figments of early Christian imagination.

The Non-Canonical Gospels

The vast majority of the non-canonical gospels are much later than the biblical gospels and derive their knowledge of Jesus from these earlier writings. It's possible however, that some of the extra-biblical gospels preserve historically accurate traditions about Jesus that were not preserved in the biblical materials. After all, Jesus said and did much more than could be squeezed into the four canonical gospels, as the Gospel of John clearly states (John 20:30). It's always possible that some of these sayings and actions were preserved in non-biblical sources.

The one non-canonical gospel that has the best chance of containing information about Jesus that is not dependent on the biblical gospels is The Gospel of Thomas , though many scholars have argued that the writer of this gospel in fact used the canonical gospels. Dating of The Gospel of Thomas is precarious and disputed, but it could have been written as early as the last decades of the first century A.D. More importantly, it seems to preserve traditions about Jesus that could be older and, in some cases, independent of the biblical gospels.

The Gospel of Thomas is a collection of 114 sayings attributed to Jesus. There is almost no narrative. A majority of the sayings are paralleled in the biblical gospels, sometimes quite closely. (See, for example, Thomas 20, which is the Parable of the Mustard Seed.) Many of the sayings in The Gospel of Thomas reflect Gnostic theology and surely didn't come from the mouth of Jesus. A few of the sayings, however, could reflect something Jesus actually said, even though not found in the biblical gospels. For example, "Jesus said, 'He who is near me is near the fire, and he who is far from me is far from the kingdom'" ( Thomas 82). We can't prove that Jesus said this, of course, but he might have.

The Gospel of Thomas , even though it paints Jesus with a Gnostic brush, nevertheless provides independent evidence that Jesus was a wise teacher who used clever sayings and parables to pass along his message. Central to this message was the proclamation of the "kingdom" of God - an authentic echo in Thomas of Jesus' own preaching.

Summary

|

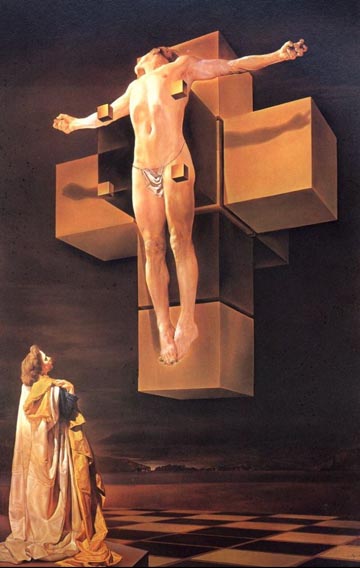

If all we had were the second-century Christian writings, we'd have a hard time sorting out what Jesus really did and said. The gulf between orthodox and heterodox treatments of Jesus was wide and growing wider in this century as Gnostics claimed Jesus as their heavenly redeemer while orthodox Christians insisted that his ministry included far more than revelation. At it's core, they argued, it had to do with his death and resurrection, something the Gnostics rejected, prefering a revealer who didn't really suffer.

But, I'm glad to say, we don't have only the second-century writings. In fact we have access to texts from the earliest days of Christian faith, writings which are collected in the New Testament. To these writings I'll turn in my next posts. |

Salvador Dali's "Crucifixion" is a modern example of a Gnostic Christ, who does not really suffer. |

Part 5: New Testament Sources (not Gospels)

When we consider New Testament sources for knowledge of Jesus, immediately we think of the four gospels. Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John do indeed provide most of what we know about the life and ministry of Jesus. But from the rest of the New Testament we actually learn some of what is most important about Jesus.

People are often surprised to learn that the gospels are not the earliest writings of the New Testament. Though they tell the story of Jesus, they were written anywhere from thirty to sixty years after his death. Most of Paul's letters were written earlier, some less than twenty years after Jesus' death. Thus the oldest written information we have about Jesus comes in the Pauline letters.

Paul did not write much about Jesus' earthly life and ministry. He rarely quotes sayings of Jesus, though there are a few quotations (for example, 1 Corinthians 11:23-25) and a larger number of "echoes." The apostle did, however, frequently talk about the death and resurrection of Jesus. Take 1 Corinthians 15:1-6, for example. Here Paul writes:

1 Now I would remind you, brothers and sisters, of the good news that I proclaimed to you, which you in turn received, in which also you stand, 2 through which also you are being saved, if you hold firmly to the message that I proclaimed to you--unless you have come to believe in vain. 3 For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, 4 and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures, 5 and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. 6 Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have died. 7 Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles.

When you peel back the theological interpretation, at the historical core Paul says that Christ died, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day, and that he appeared to Cephas (Peter) and many other disciples. There isn't anything about the life of Jesus here because Paul focuses on that which lies at the center of the Christian good news: the death and resurrection of Christ.

What's particularly noteworthy about this passage is that Paul didn't make it up when writing 1 Corinthians. He is reminding the Corinthians of what he had passed on to them previously, and this key content Paul received from Christians before him. In other words, this brief description of Jesus, which appears in a letter written about twenty years after his death, includes older oral traditions that have been passed on to Paul. In this passage, therefore, we glimpse one of the very oldest historical records about Jesus. And we see that the facts about Jesus have already been given a profound theological interpretation: Jesus died "for our sins in accordance with the scriptures," and he was raised "in accordance with the scriptures."

If we had time to comb through the rest of Paul's writings, and the rest of the New Testament writings besides the gospels, we'd find more about Jesus, but most of this material would concern, not his earthly life and ministry so much as his death and resurrection, and their meaning for salvation.

Why is this important to know? Well, for one thing it is reassuring for Christians to realize that the core of our faith lies in the oldest and most reliable portions of the New Testament. This is especially significant because there are scholars and pseudo-scholars who claim that the real Jesus was just a moral teacher, not a Savior who died for sins and was resurrected from the dead. But the facts run in the opposite direction. The earliest sources show that the center of early Christian belief in Jesus contained affirmations about his death and resurrection. These events were interpreted in the earliest days of Christianity as the way God had brought salvation to the world. From the early Christian perspective, Jesus was first of all the Messiah, the Savior, and the Lord.

Part 6: New Testament Sources -- Gospels

Finally, after a week's worth of blogging on the question "How can we know anything about the real Jesus?", I get to the best evidence we have: the New Testament gospels.

Why are Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John our most reliable sources for knowledge of the real Jesus? If you've been reading along, you know that I'm bracketing for the moment the whole question of the divine inspiration of these texts. Rather, I'm looking at them from the perspective of historical inquiry, and from this vantage point, the biblical gospels are the most trustworthy sources we have. Most scholars agree on this point. (A minority of scholars, many of whom are fellows in the notoriously skeptical Jesus Seminar, prefer The Gospel of Thomas. But their reasoning for preferring this gospel is circular. They like it as a historical source because it gives them the Jesus they have predetermined to like.)

Why are the biblical gospels reliable sources for information about the real Jesus?

1. They are the oldest of the gospels, written within 30 to 60 years after Jesus' death. Among all of the non-canonical gospels, only The Gospel of Thomas may have been written in this time period, though evidence for this dating is not strong.

2. The biblical gospels use older written sources and oral traditions about Jesus. Luke, for example, writing in the 70's or 80's, had access to much older information about Jesus (see Luke 1:1-2).

3. The authors of the gospels either knew Jesus personally (as is traditionally believed about Matthew and John) or they knew people who had known Jesus personally (as is traditionally believed about Mark, who is said to have known Peter).

4. Because we have four early gospels, we can evaluate their historicity comparatively. Most scholars believe that Matthew and Luke actually used Mark as a source, which further verifies the reliability of Mark. (A minority of scholars believe that Mark and Luke used Matthew as a source.)

5. The four gospels agree in their essential portrayal of Jesus, who: was a Jewish man; ministered during the reign of Pontius Pilate, first in Galilee, and ultimately in Jerusalem; called disciples to follow him; included women among his retinue; taught about God and God's kingdom; did miracles, especially healings; was misunderstood by many; experienced conflict with Jewish leaders; spoke and acted in a way that undermined the temple in Jerusalem; spoke and acted in ways that suggested he was God; was crucified at the time of Passover under the authority of Pontius Pilate with the cooperation of some Jewish leaders in Jerusalem; was raised from the dead on the third day; was seen after his resurrection by his followers, with women playing a central role. Notice that many of these details are consistent with what we learned from the other earliest sources of information about Jesus, including the Roman and Jewish sources.

6. Many of the historical references in the New Testament gospels can be proved to be accurate. For example, where the gospels mention the political leaders of Palestine (Herod the Great, Herod Antipas, Herod Philip, Pontius Pilate, Emperor Augustus, Emperor Tiberius), they get the facts right.

7. The gospel writers had a great interest in preserving the truth about Jesus. Luke introduces his gospel by claiming to have studied older sources carefully so that he might write "an orderly account" of what happened to Jesus. He did this so that the reader might have certainty about Jesus' life and ministry. (See Luke 1:1-4.) Critics who accuse the gospel writers of playing fast and loose with the truth overlook the fact that these writers often put their own lives on the line for what they believed about Jesus.

8. The gospels underplay the miracle stories. Of course if you're not used to reading miracle stories, one of the first things that strikes you as you read the gospels is the prevalence of the supernatural. But if you read these stories carefully, you'll notice how matter-of-fact they are in the descriptions of Jesus' miracles. This doesn't prove that the miracles really happened, of course, but it does show that the gospel writers weren't exaggerating for dramatic effect.

| 9. The gospels portray Jesus accurately even when his words or deeds might have been hard to understand or even contrary to the "agenda" of the early church. For example, the gospels preserve comments of Jesus that hardly support the early church's outreach to non-Jews (Matt 10:5-6; Matt 15:24). More striking is the inclusion of Jesus' prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane, where he asks his Father to "remove this cup from me" (Mark 14:36). It's hard to imagine early Christians making up this scene or even passing it on unless they were stubbornly committed to preserving the truth about Jesus. |

|

|

10. I have saved one of the most persuasive arguments for the historical reliability of the gospels to the end. Ironically, it doesn't have to do directly with Jesus, though it does concern the disciples of Jesus and the way they're portrayed in the biblical gospels. The disciples start off well enough, leaving everything to follow Jesus (Mark 1:16-20). But throughout the rest of the story they are often seen as foolish, faithless, and even self-serving. For example:

· They consistently misunderstand Jesus (e.g. Matt 16:5; Mark 10:13-14, 35-40; John 12:17)

· They are self-seeking, concerned for their own greatness and glory (Mark 9:34, 10:35-37)

· They lack faith in God or Jesus (e.g. Matt 8:26; Matt 14:22)

· They are rebuked by Jesus for being people "of little faith" (Matt 8:26). Worse still, Jesus once expresses his exasperation over the disciples, "You faithfulness and perverse generation, how much longer must I be with you?" (Matt 17:17).

· They abandon Jesus in his hour of greatest need, sleeping while he asks them to join him in prayer at Gethsemane (Mark 14:32-43). Then, when he is arrested, all of them desert Jesus and run away to save their own necks (Mark 14:50). None of the male disciples are present at the cross, except for "the disciple whom Jesus loved" (probably John, John 21:20).

· After the resurrection, the disciples disbelieve Mary's report that he is risen (Luke 24:11) and some doubt (or are hesitant) even when they see the risen Christ (Matt 28:17).

If this isn't bad enough, Simon Peter, one of the leading disciples and the one whom early Christians understood to be the dominant leader of the church, outdoes the others by modeling how not to respond to Jesus.

· Although Peter has enough faith to get out of the boat when Jesus is walking on the water, he soon becomes afraid and sinks, needing Jesus to rescue him before rebuking him for his doubt (Matt 14:30-31).

· When Jesus first reveals his pending death, Peter actually rebukes Jesus, who then rebukes Peter in stunning language: " Get behind me, Satan! For you are setting your mind not on divine things but on human things" (Mark 8:32-33).

· Peter doubly misunderstands the point of Jesus' foot washing (John 13:5-10).

· Peter is among the disciples who fall asleep at Gethsemane and flee when Jesus is arrested (Mark 14:50).

· Peter denies Jesus repeatedly, even after he boasted that he would never do so (Mark 14:66-72).

If you haven't read through the gospels recently, you may suppose that I have simply highlighted the negative aspects of the description of the disciples. But, truly, there isn't much else there! The closest followers of Jesus - the male ones, at any rate - are mostly seen as bumbling, confused, and self-centered.

Now, let me ask you: Is this something you'd expect to find in the literature of a movement in which the disciples turned out to be the primary leaders? Do movements generally pass along stories of their founders in which they look foolish? On the contrary, most stories told by members of an organization about leaders of that organization tend to emphasize the leaders' strengths while minimizing or eliminating any evidence of their weaknesses.

|

Yet, here we have some of the foundational literature of the early Christian movement, the movement that hailed Peter and his colleagues as its leaders, and this literature paints these leaders in a most unflattering light. What could possibly explain this apart from a rigorous commitment by the gospel writers to the truth no matter what? |

St. Peter's Basilica in Rome |

It's popular in postmodern criticism of the gospels to see in them political power struggles. The Da Vinci Code has popularized this theory, holding that the biblical gospels were canonized because they were useful to augment the power of the Catholic Church. Yet, would any institution concerned primarily about its own power choose as its fundamental texts gospels that reflected so poorly on its founders?

The fact that the New Testament gospels tell true and embarrassing stories about the disciples demonstrates how reliable they are as historical sources in general, and as sources for Jesus in particular.

Let me close with a pastoral comment. The fact that Jesus' closest disciples had such a hard figuring him out and following him gives me hope. I've been a Christian for forty years and sometimes I feel like I'm just getting started in relationship with Jesus. My own discipleship is terribly flawed, and this can be discouraging to me. Yet, when I read about the buffoonery of the disciples, I'm encouraged. Jesus obviously isn't looking for perfection (or even close!), but for people who keep following him even when they mess up royally. Thank God!

|

If you are looking for scholarship on Jesus that is careful and yet readable, you might find my book Jesus Revealed to be helpful. Each chapter summarizes historical evidence that helps us to understand Jesus, yet in a way that is meant for non-specialists. Plus, each chapter also connects the historical discussion to our personal faith today.

For more information on this book, click here. |

Home

|