| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

Happy TIME

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2005 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com . Thank you.

Happy TIME

Part 1 of the series “Happy TIME”

Posted at 11:30 p.m. on Tuesday, January 11, 2005

The cover of the latest TIME magazine caught my attention as I sorted through the mail yesterday. “The Science of Happiness” it proudly proclaims, illustrated by an atomic happy face. Among the bullet points beneath the headline I saw something else that grabbed my interest: “Does God want us to be happy?” Now there’s something I’ve got to read, I thought. And so I did.

TIME’s focus on happiness is the subject of a 68-page special feature (counting the ads), with numerous articles, including: “The New Science of Happiness,” “The Biology of Joy,” “The Real Truth About Money,” and “The Power to Uplift.” The writers examine happiness from a variety of perspectives, including psychological, sociological, biological, and theological points of view. All in all I found the collection of articles to be informative and engaging. I’ll have more to say about the theological pieces later. But at this point I’ll simply mention that they seemed basically fair and even-handed.

TIME begins by spotlighting a new field of psychology, called positive psychology. Whereas the bulk of psychology in the past has focused on mental illness, positive psych looks at healthy, happy people and asks: What makes them this way? |

|

| |

The January 17 issue of TIME |

The answers published by positive psychologists will seem surprising to some people, perhaps patently obvious to others. For example, many Americans believe that money and happiness are inextricably connected. The more money you have, the more you will be happy, we think. But psychological research shows that once a person has emerged from poverty, which is correlated with unhappiness, having more money does not necessarily lead to having more happiness. In fact, psychological researcher Edward Diener found that the very richest Americans were “only a tiny bit happier than the public as a whole” (A33).

There are many other fascinating findings and nuggets of wisdom in TIME’s special report. I’ll comment on some of these in the days ahead, especially those that focus on matters of faith and theology. But today I want to step back and reflect, not so much on the content of the TIME report, but on the fact that happiness gets so much attention from one of America’s major news magazines.

Identifying and experiencing happiness lies close to the American heart. Our very own Declaration of Independence, for example, contains the classic American statement: “We hold these truths to be self-evident — that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” Commenting on the modern implications of this statement, George Will once wrote: “Modern Americans travel light, with little philosophic baggage other than a fervent belief in their right to the pursuit of happiness” (in The Pursuit of Happiness, and Other Sobering Thoughts, 1978).

One could see the TIME report as yet another instance of American preoccupation with the self. I can just hear some critic saying, “See, while people in Southeast Asia are fighting for their very existence, Americans have the leisure to ponder the nature of happiness.” I would agree that such reflections are a luxury, though they’re hardly uniquely American. Aristotle spent plenty of time thinking about happiness over two millennia ago in Greece. I would also agree that we Americans can become so consumed by our pursuit of personal happiness that we can overlook the happiness, or even the basic well-being of others. “But,” I would respond, “isn’t our freedom to reflect upon happiness and to pursue it what we want for the disadvantaged people of the world?” The problem is not that Americans have this opportunity, but that others don’t.

Furthermore, I think the substance of the TIME report might very well help us to be less preoccupied with our own pleasures and more interested in doing things of significance, like helping people in need. The more one thinks about happiness, the less one is inclined to seek selfish pleasures, and the more one will be devoted to the happiness of others.

I’m going to spend my next few posts reflecting on what I have found in TIME, especially evaluating this in light of Christian theology. If you don’t have access to the magazine, you can find the articles online.

I’d like to close by citing one of the suggestions found in the TIME report, in a sidebar called “Eight Steps Toward a More Satisfying Life” (p. A8). Here is step number 1, according to the University of California psychologist Sonja Lyubomirsky: Count your blessings. Sheesh! This is exactly what my grandmother said to me about a thousand times. So if a university psychologist and my grandmother agree, it’s gotta be true.

Does Religion Make You Happier?

Part 2 of the series “Happy TIME”

Posted at 10:45 p.m. on Wednesday, January 12, 2005

Among the collection of articles in TIME magazine’s current special on happiness, two are specifically focused on religious or theological themes. The first is called “The Power to Uplift.” The subtitle of this article by Pamela Paul reads, “Religious people are less stressed and happier than nonbelievers. Research is beginning to explain why.” (If you’re a TIME subscriber you can access this article from this page.)

A Brief Synopsis of the Article (A46-A48)

Interest in the relationship between mental health and religion has skyrocketed in the last two decades. Findings have shown that religious people tend to be both healthier and happier than non-religious people. Researchers have begun to explain why.

For one thing, religious people tend to have lots of social support and connection, one of the chief ingredients in happiness. They also live with “the sense of purpose and grand design that religious faith provides.” This helps people both to live meaningfully and to make sense of life’s difficulties.

Ironically, religion helps us to be happy by telling us not to engage in behaviors highly correlated with unhappiness: adultery, drug use, etc. In a day when the freedom to do whatever we want seems to be a component of happiness, this might seem counterintuitive. But the fact is that religious prohibitions actually seem to focus people in a more productive pursuit of happiness. (So let’s hear it for the Ten Commandments’ “thou shalt nots.”)

Although religion in general tends to make one happier, Protestants turn out to be happier than Catholics and Jews. This may have to do with Protestant confidence in an afterlife, especially vis-à-vis Jews.

Agnostics and atheists who have a framework of belief and a strong community can also be happy, rather like religious folk. And though some doubt the candor of religious reports of happiness, TIME concludes that, for many, the relationship between faith and happiness is a strong and demonstrable one. |

|

| |

One of the most profound and prolific writers on the relationship of happiness (or joy, as he calls it) and faith is C.S. Lewis, some of whose writings are collected in The Joyful Christian. |

My Response:

First, I must say I was impressed by the general tone and thesis of the article, both of which were quite positive about religion. Although the possibility of religious people exaggerating their happiness was raised, Pamela Paul rejected that explanation in favor of the more obvious and fair one.

Second, the article rightly points out that what religion provides is essential to human happiness. Take human community, for example. The opening article in the TIME series argued that being connected to others contributes most of all to happiness (A9). “Almost every person feels happier when they’re with other people,” observes a leading positive psychologist. So, given that fact that religion provides a principal context for genuine community, we should expect a higher level of happiness among religious people.

Third, I was surprised – and, I must confess, gratified – by a couple of the findings reported in the article. The first is this: “Studies show that the more a believer incorporates religion into daily living – attending services, reading Scripture, praying – the better off he or she appears to be on two measures of happiness: frequency of positive emotions and overall sense of satisfaction in life” (A46). Now this, you must understand, is music to a preacher’s ears. How often I try to encourage my flock to live out their faith each day. Now I’ve got the evidence of psychological research on my side. We should live out our faith, not only because it’s right to do so, not only because it honors God, not only because the world needs this from us, but also because by doing so we will be happier.

The second surprising and gratifying finding is: “Attending services has a particularly strong correlation to feeling happy" (A46). Wow! There you go! Attend worship services and you’ll be happy. Skip church and you’ll be miserable. Well, okay, I exaggerate a bit. But I find this correlation to be most encouraging. Of course it also makes sense to me. But it's nice to see my intuitions backed up by research.

Now, let me add, since I haven’t seen the data behind this conclusion, I’m wondering if the “go to church and you’ll be happy” argument really works in just this way. It may be that people who take their faith seriously are happy, and that they also tend to go to church. In other words, church attendance may be, not the primary cause of happiness, but rather the result of an active faith which itself leads to happiness.

There is a danger in all of this for preachers and churches, however. It’s the danger of getting so caught up in the happiness-creation business that we forget our true vocation. If, as a preacher, I’m too eager for people to feel happy, then I might be tempted to downplay some of the bad news that I need to dole out, things having to do with sin and the like. If I focus too much on people's immediate happiness, then I may neglect my first calling as a preacher, which is to tell the truth whether people like it or not. (I actually do believe that an honest discussion of sin can lead to greater happiness, because if I own up to my sin, confess it, and receive God’s forgiveness, then I will be happier. But along the way to this sort of happiness I must deal with the bad news of my sinfulness.)

A closing thought from the poet Ogden Nash (from “Interoffice Memorandum in I’m a Stranger Here Myself). Something to think about:

There is only one way to achieve happiness on this terrestrial ball,

And that is to have either a clear conscience, or none at all.

Does God Want Us to Be Happy?

Part 3 of the series “Happy TIME”

Posted at 9:45 p.m. on Thursday, January 13, 2005

The current issue of TIME magazine contains a special report on happiness, which includes sixteen articles or opinion columns, not to mention a bunch of additional sidebars. Two of these pieces focus directly on questions of religion and theology, though many other articles refer to religion as well. In yesterday’s post I examined the article, “The Power to Uplift,” which shows that religious people are demonstrably happier than non-religious folk. Today I’m going to begin to delve into the next item, an op-ed piece by David Van Biema entitled “Does God Want Us to Be Happy?” (A51).

Before I analyze Van Biema’s column, however, I must first confess a visceral reaction to the title, a negative one at that. You see, all too often in my pastoral ministry the claim “God wants me to be happy” is immediately followed with “Therefore I’m going to do something which otherwise would be wrong.”

Let me provide a specific example. Some time ago a man from my congregation, I’ll call him Chris, came to meet with me. “My marriage is in trouble,” he began. “I don’t think we’re going to make it.”

“That’s terrible,” I responded. “Tell me what’s going on.”

And so Chris began a long, sad story of failed communication, uncommon goals, and separate lives. The punch line? “So I’m going to leave my wife.”

“I can understand why you’re upset right now," I responded, "but have you thought about how you might be able to improve your marriage? Have you given this the effort it deserves? And what about your children? You have two young children. Do you really think it’s the best thing for them that you divorce your wife? Then there’s God’s strong biblical directive that you stay married. How can you feel so certain that divorce is the best thing?”

“Well,” Chris answered, “I am worried about my kids. And I know God doesn’t approve of divorce. But I’m just not happy. And I know God wants me to be happy. So I’m leaving my wife.” |

|

| |

When you think of divine figures among the world’s religions, you don’t often think of them as appearing happy. An exception can be found on the ruins of the Angkor Thom temple in Cambodia, with its giant smiling Buddhas (Bodhisattva Lokesvara, “lord of the world”). These images are said to reflect that compassion and power of the Buddhist lord.

|

Now you know why my gut wrenches when I encounter the question “Does God Want Us to Be Happy?” Time and again the belief that “God wants me to be happy” is a justification for behavior that is selfish, hurtful to others, and, contrary to clear biblical teaching.

Of course there is a tragic flaw in Chris’s argument, even if you grant the primary premise that God wants us to be happy. The flaw lies in Chris’s belief that he actually knows how best to be happy. Although I didn’t mention it in my meeting with him, I might well have responded to Chris by saying, “Yes, I agree that God wants you to be happy. And that’s precisely why I think you should stay in your marriage.”

Any consideration of God’s bearing on our happiness involves at least two questions:

1. Does God in fact want us to be happy?

2. How, according to God, do we find happiness?

As this series continues, I will attempt to answer both of these questions.

Before I do, however, I want to step back for a moment and talk about my source of authority for my answers (and, I hope, for most of my writing, except the silly stuff). If you’ve been reading my blog for a while, you know that I come at things from a biblical perspective. I try to apply the wisdom of Christian Scripture, both Old and New Testaments, to whatever question is at hand. I do this, not only because I believe that the Bible has lots of good ideas, but mainly because I believe it is in some strong sense the Word of God. Though I do not believe that God dictated every word of the Bible in a way that diminishes the genuinely human aspect of the book, I affirm the full inspiration and trustworthiness of Scripture. In a way we’ll not fully understand this side of heaven, God was at work through the authors of Scripture, making sure that they wrote truthfully.

Now let me hasten to add that you don’t have to agree with me about the authority of the Bible in order to read or even benefit from my blog. You might well agree with things I derive from Scripture, not because of their divine origin, but because they make sense to you. I welcome all readers, no matter what you’re theological or philosophical convictions. But, every now and then I try to let folks – especially newer readers – know where I’m coming from philosophically. That will enable you both to understand my points and to critique them.

Thus when it comes to the questions of God and happiness, I might rephrase them in this way:

1. Does the Bible reveal a God who wants us to be happy?

2. How, according to Scripture, do we find happiness?

Well, I’ve now spent over 800 words fessing up to my feelings and presuppositions. I’m going to sign off now. Tomorrow I’ll jump into the subject at hand, and begin to answer the question “Does God want us to be happy?”

Let me close once more with a quotation to consider. This one is from the book The Second Sin by psychiatrist and author, Thomas Szasz

Happiness is an imaginary condition, formerly often attributed by the living to the dead, now usually attributed by adults to children, and by children to adults.

Does God Want Us to Be Happy Now?

Part 4 of the series “Happy TIME”

Posted at 9:45 p.m. on Friday, January 14, 2005

In the recent TIME magazine series on happiness, David Van Biema has authored a “viewpoint” column seeking to answer the question: Does God want us to be happy? I’d like to tackle this question also, and since there are hundreds of ways to approach it, I thought I’d let Van Biema’s article serve as a jumping off point. Here’s how his piece begins:

If you are interested in God's position on human happiness, please proceed to Chapter 12 of Luke, where Jesus seems to take a slap at Ecclesiastes. The author of the earlier book, a seen-it-all, done-it-all type attuned to life's brevity, famously observed, "Man hath no better thing ... than to eat, and to drink and to be merry" in the time "God giveth him under the sun." Jesus, in a parable, puts these very words in the mouth of a man who reaps an unexpected bumper crop, plans bigger barns to hold it and anticipates a kind of Miami retirement: "And I will say to my soul, Soul, thou has much goods laid up for many years; take thine ease, eat, drink and be merry." But then Jesus lowers the boom: "God said unto him, Thou fool, this night thy soul shall be required of thee: then whose shall those things be?" The message: happiness in this life is—emphatically—beside the point. (A51)

Is this God’s position on human happiness? Does God believe that happiness in this life is beside the point? Is this what the Bible teaches? Is this what Jesus means?

I appreciate Van Biema’s effort to let Scripture speak, not to mention his high regard for the teaching of Jesus. Yet I’m not altogether sure that Van Biema gets things quite right. (As an aside, I also find his use of the King James Version of the Bible to be peculiar and distracting. Very few contemporary writers would use this old translation since it tends to make the biblical text, which was written in popular, common Greek, seem obscure and antiquated.)

According to Van Biema, “Jesus seems to take a slap at Ecclesiastes.” The writer correctly sees a connection between the words of the rich man in Luke 12 and Ecclesiastes. For example, Ecclesiastes 8:15 says,

So I commend enjoyment, for there is nothing better for people under the sun than to eat, and drink, and enjoy themselves [KJV, be merry], for this will go with them in their toil through the days of life that God gives them under the sun.

It may well be, however, that Jesus and the author of Ecclesiastes share more in common than it appears on the surface. The Book of Ecclesiastes is, after all, a notoriously complex document with multiple ironies. Nevertheless, Jesus clearly “takes a slap” at those who would see life mainly as an opportunity for bodily pleasures. |

|

| |

A modern statement akin to that of Ecclesiastes is Peggy Lee's song "Is That All There Is?" For an excerpt, click here. |

Yet in telling the story of the foolish rich man, is Jesus teaching that all happiness in this life is beside the point? Note the story and its ending once more. A rich man stores up lots of earthly treasures for himself and thinks that he will be able to enjoy these for many years by eating, drinking, and making merry. But that night he dies, thus losing the benefits of all he had accumulated. Jesus concludes by saying, “So it is with those who store up treasures for themselves but are not rich toward God” (Luke 12:21).

|

Surely Jesus implies that true happiness is not to be found in earthly treasures. But to conclude from this that Jesus opposes earthly happiness in general is to equate earthly treasures with earthly happiness – exactly the point Jesus opposes, and exactly the equation Van Biema himself makes. In other words, both Van Biema and the rich man in the parable make the same mistake. They talk as if earthly happiness is to be found in having many possessions. Jesus clearly refutes this notion. But he does not state, nor even imply, that happiness in this life is beside the point. Finding happiness through possessions, yes, this is beside the point. But earthly happiness itself is in no way overruled by this parable. |

For a more recent rendition of "Is That All There Is?" by a world-class recording artist, click here. |

|

This discussion leads us to an essential and fairly obvious conclusion: there are different kinds of happiness, and, among other things, these derive from different sources. There is the kind of happiness that the rich man in Jesus’s parable had, a shallow and selfish happiness that comes from having many possessions. Yet there is a very different kind of happiness that comes from sharing one’s possessions with others. This sort of happiness, which we can experience this side of heaven, is touted in Scripture. Consider, for example,

Happy are those who consider the poor;

the Lord delivers them in the day of trouble (Psalm 41:1)

Those who despise their neighbors are sinners,

but happy are those who are kind to the poor (Proverbs 14:21)

Jesus, I would argue, fits squarely within this Jewish tradition of seeing happiness, not as an experience that lies exclusively in the future, but as something that can be experienced now, at least in part. In my next post I’ll pursue this line of thought a bit further, noting, once again, where I disagree with Van Biema’s interpretation of Jesus.

Finally, a quotation to ponder, from Sigmund Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents:

What we call happiness in the strictest sense comes from the (preferably sudden) satisfaction of needs which have been damned up to a high degree.

The Secret of a Happy Life???

Part 5 of the series “Happy TIME”

Posted at 9:55 p.m. on Saturday, January 15, 2005

So what’s the secret of a happy life? A rather surprising answer has been floating around in the news this week. If you missed the story, let me give a brief synopsis.

Jane Lathrop Stanford Middle School in Palo Alto, California had its third annual “Career Day” last week. One of the speakers was William Fried, a salesman from Foster City, California. His presentation, entitled “The Secret of a Happy Life,” included a handout with 140 potential careers, including “exotic dancer” and “stripper.” When asked by a student about this unusual inclusion, Fried explained that strippers can make as much as $250,000 per year. He added, and here I quote from the San Francisco Chronicle,

“a larger bust -- whether natural or augmented -- has a direct relationship to a dancer's salary.” He told the students, "For every two inches up there, it's another $50,000," according to Jason Garcia, 14.

Whether being a stripper contributes to a happy life or not, you can be sure that Mr. Fried’s indiscretion did not make the life of school Principal Joseph Di Salvo any happier. After news of Mr. Fried’s commendation of stripping reached the mainstream media, Mr. Di Salvo was forced to write a letter of explanation to parents. “Sometimes middle schools are like a box of chocolates,” Di Salvo wrote. “You never know what you are going to get. Certainly, this is exactly how some of us felt at JLS yesterday.” Hey, since when did Forrest Gump become a middle school principal?

In reading Mr. Di Salvo’s letter, I found it curious that no apology was offered for Mr. Fried’s presentation. In fact, the principal's response seems pathetically weak to me. Here’s exactly what he wrote concerning the incident and his response to the students:

I met with your children today to discuss the incident and the comments attributed to Bill Fried, Salesperson. Mr. Fried, in one of his sessions, responded to student questions about two careers he listed in alphabetical order among scores of careers. These two careers were exotic dancer and stripper. I believe these were very inappropriate to list, although some students thought that, if these are real careers, they should be listed. The students felt Freid [sic] crossed the line only marginally. Primarily, the message was to follow your dream, do something you’re good at and love and you will be happy the rest of your life.

Please use this opportunity to open up a dialog, as I hear many of you have already done, to discuss the theme of Fried’s presentation, the media’s response, and any other topics that are spawned by the conversation. Perhaps, in this black cloud, there is a silver lining.

I don’t know about you, but this letter doesn’t exactly restore my confidence in Jane Lathrop Stanford Middle School. Principal Di Salvo believes that it was “inappropriate” to list exotic dancer and stripper as viable careers for middle school students, but he adds without comment that “some students thought that, if these are real careers, they should be listed.” Does Mr. Di Salvo believe that his opinion and that of these students are equal? Did he correct the students? Did he explain why Mr. Fried was out of line? We don’t know from the letter. I must confess that the feeling I get from the letter is that very little moral instruction went on, either in Mr. Fried’s presentation, or in Mr. Di Salvo’s conversation with the students. (Of course we should probably be glad that Mr. Friend didn't delve into the realm of morals.)

There is a huge irony here that hasn’t received any comment in the press, at least to my knowledge. It’s the fact that this scandal happened at Jane Lathrop Stanford Middle School. Jane Stanford was the wife of Leland Stanford, the founder of Stanford University. This university was one of the first in the world to admit women as students, partly under the progressive leadership of Mrs. Stanford. After Mr. Stanford died in 1893, however, Mrs. Stanford became concerned about the behavior of some of the female students, commenting that they had become “quite lawless and free in their social relations with young men.”

Later, she became worried that Stanford was accepting too many women as students. If this pattern continued, she reasoned, Stanford would become a women’s college. So in 1899 she issued the following statement: “

"Whereas the University was founded in memory of our dear son, Leland, and bears his name, I direct that the number of women attending the University as students shall at no time ever exceed 500.... I mean literally never in the future of the Leland Stanford Junior University can the number of female students at any one time exceed 500."

This was the explicit policy of Stanford University until 1933, when university trustees managed to wriggle through a loophole that allowed them to admit more women. |

|

| |

Jane Lathrop Stanford

|

Jane Lathrop Stanford was a colorful woman, who dabbled in spiritualism in an attempt to contact her dead son, Leland Stanford Jr. Moreover, her death is shrouded in mystery, as many scholars believe she was poisoned, and that her murder was covered up by David Jordan, who was Stanford’s president at the time of Mrs. Stanford’s death.

Whether poisoned or not, everything I’ve learned about Mrs. Stanford suggests that she must be rolling over in her grave these days, since the middle school named after her is now famous for touting the merits of exotic dancing and stripping.

My guess is that Bill Fried’s overall level of happiness may have dropped a bit in the last week. Perhaps he’d do well to reconsider the connection between ethical living and a happy life.

When Do We Get to Be Happy?

Part 6 of the series “Happy TIME”

Posted at 11:55 p.m. on Sunday, January 16, 2005

In part 4 of this series I began to examine David Van Biema’s article “Does God Want Us to Be Happy?” I argued that Van Biema misses the point of Jesus’s parable of the rich man who finds happiness in his riches but then suddenly dies. According to the article, the parable shows that “happiness in this life is – emphatically – beside the point.” Yet Jesus, consistent with his Jewish tradition, was not denying the value of earthly happiness in general. Rather, he was showing the folly of happiness that comes from earthly riches.

Van Biema’s mistaken perspective receives further elaboration in the next couple of paragraphs:

[Unlike in Hinduism], in Western Christianity the question [of happiness] has often been framed more narrowly: whether God wants us to savor this life or whether its only true joys are the anticipation of heaven and obedience to his sometimes inscrutable will.

Don’t recall the debate? It was a doozy while it lasted, especially since Jesus was not obviously consistent on the topic. (Matthew’s Beatitudes see joy almost entirely in the future tense, but John promises a this-worldly “whatsoever ye shall ask in my name, that will I do.”)

Van Biema is correct in noting that the discussion of happiness has, among Christians, often been framed as an either-or question, in which God wants us to be happy either in this life or in the next, but not both. Whether this should be the case, however, remains to be seen.

I would agree with Van Biema that Jesus was not obviously consistent on the matter of happiness. (One might argue that Jesus’s teaching was rarely obvious on anything. Jesus himself seemed to say as much in Matthew 13:13.) Yet I would not agree with Van Biema’s estimation of the Beatitudes in Matthew. Clearly there is a future dimension to the happiness promised in this text, but the Beatitudes do not “see joy almost entirely in the future tense.”

In case you’ve forgotten how the Beatitudes read, let me cite some of them here:

“Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

“Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.

“Blessed are the meek, for they will inherit the earth.

“Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled.

“Blessed are the merciful, for they will receive mercy.

“Blessed are the pure in heart, for they will see God.

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.

“Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. (Matt 5:3-10)

|

|

| |

This is the Mount of the Beatitudes in Galilee, near Capernaum. The Sea of Galilee is in the foreground. This is the place where, according to tradition, Jesus uttered the Beatitudes recorded in Matthew. Picture from BiblePlaces.com. |

Clearly there is a future dimension to this passage. Jesus says that certain people will be comforted, will inherit the earth, etc. This does seem to point to the heavenly future. But notice that in verses 3 and 10 we have a present tense promise, “for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.” So we have both future and present tense promises in the Beatitudes.

Moreover, Jesus did not say, “Someday the poor in spirit will be blessed . . . . Someday those who mourn will be blessed.” Rather, he spoke of their being blessed as a present tense reality, even though in many cases the source of their blessing lies in the future. Curiously, Jesus’s meaning seems to be “Blessed now are those who mourn, for they will in the future be comforted.” There is a present experience correlated with some future benefit.

Here’s a good example of where Jesus is not obvious in what he’s saying. Are the kingdom and its treasures a future reality? Or are they something we can experience in the present? Or are they somehow both? If you’ve been reading my blog for a while, or if you have studied New Testament theology, you know that “somehow both” is the right answer. In my recent series “All Things New” and in my earlier series called “What Was the Message of Jesus?” I explained how heaven is both a future and a present reality. For Jesus, the kingdom of God has arrived, and yet it is still to come in all of its fullness.

The same could be said about Jesus’s view of happiness. Yes, it lies in the future, when the sad will be comforted, the meek will inherit the earth, the hungry will be filled, and so on. But one who lives under God’s reign now can begin to experience in this life the reality of the future, including its joy.

When we grasp the present and future dimensions of Christian eschatology – as David Van Biema appears not to – then we won’t make the mistake of believing that happiness is an either/or proposition, either now or in the future. In fact it can be a both/and reality, at least in part.

By now you may be wondering where I’m getting this stuff about happiness. Don’t the Beatitudes speak of being blessed? And isn’t blessing something quite different from feeling happy?

In my next post I’ll explain why the Beatitudes do in fact relate to our present discussion of happiness, and I’ll also talk about the linguistic challenges we face in this whole conversation.

For now, let me end once again with a quotation that might spark some further reflection. This one comes from the early twentieth-century English writer, G.K. Chesterton:

Happiness is a mystery like religion, and should never be rationalized.

Happy or Blessed? Which Are We to Be?

Part 7 of the series “Happy TIME”

Posted at 11:45 p.m. on Monday, January 17, 2005

In my last post I was discussing happiness in relationship to the Beatitudes in the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 5. There, Jesus says things like:

“Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

“Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted. (5:3-4).

Differing from David Van Biema’s perspective in his TIME magazine article entitled “Does God Want Us to Be Happy?” I argued that the Beatitudes offer a happiness that is not “entirely in the future tense.” Rather, in light of the “already and not yet” eschatology of Jesus, happiness in the Beatitudes is something that can be experienced now, even though the fullness of joy lies in the future when the kingdom of God comes completely.

Yet I expect that some of my readers may be puzzled by how blithely I seem to relate the Beatitudes to happiness. In most English translations, including the KJV, NIV, and NRSV, Jesus says, “Blessed are the poor in spirit,” not “Happy are the poor in spirit.” So why, you might wonder, do I seem to equate blessedness with happiness?

| I could simply say that people who are blessed are also happy. It’s hard to imagine someone saying, “I am so blessed, but I feel miserable.” Yet my reason for seeing happiness in the Beatitudes is more a matter of linguistic precision than anything else. If you were to read these verses from Matthew 5 in Greek, you'd find the word makarios behind the English word blessed. (People as old as I am might remember a president of Cyprus who was called Archbishop Makarios. The Greek word is the same.) Makarios can be translated as “blessed,” but even then the sense would be closer to “happy” or “fortunate” than “blessed by God.” When the New Testament writers wanted to emphasize the divine character of blessing, they used a different word (eulogetos, related to our English word “eulogy”). So, when modern translations use “blessed” in the Beatitudes, they run the risk of over-spiritualizing the original meaning. Jesus is not saying, “God gives good gifts to the poor in spirit,” though this is surely true. Rather, he is making a rather stunning claim that the poor in spirit are in some sense also happy. |

|

| |

A statue of Archbishop Makarios, near his birthplace. It’s rather hard to tell from this statue if he was happy or not. |

Of course this raises another obvious question: How can people who are poor in spirit, mourning, meek, and so forth be happy? The answer to this question draws upon the eschatological orientation of Jesus, as I have explained earlier. But it also speaks to the true meaning of happiness. It isn’t a momentary pleasure, or even pleasure at all. Rather, the happiness promised by Jesus is much deeper and more lasting. It can’t be squelched by those things that almost always muffle our delight: sadness, hunger, thirst, etc.

Jesus’s use of makarios mirrors the Old Testament use of the term ’ashrei. This Hebrew term also walks the fine line between happiness and blessedness. Many modern translations stay with the classic “blessed” of the King James Version, though others have waded into the murky waters of happiness (notably the NRSV). In Psalm 1, for example, both the KJV and the NIV begin: “Blessed is the man. . . .” The NRSV uses “Happy” while the NLT paraphrases as “Oh, the joys. . . .” I would argue that the NRSV and NLT are closer to the sense of the Psalm, with the NLT’s “Oh, the joys” avoiding the possible shallowness of "happy." Michael L. Brown, in a fine entry in the New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis has this to say about ’ashrei: “the most accurate rendering of ’ashrei is probably ‘truly happy,’ although for translation purposes, how happy, or simply happy, may often be preferred” (1:171).

As in the case of makarios, I appreciate the attempt of the biblical translators to avoid the implication that life is to be a matter of fleshly, temporal pleasures. But by rendering ’ashrei as “blessed,” they run the risk of obscuring the extent to which God does intend for his people to experience genuine happiness in this life, even before we taste the richest joy of the life to come.

As long as we keep in mind the deeper sense of happiness implied in Scripture, it seems quite clear to me that God does want us to be happy. But, having said this, I fear I might have opened Pandora’s box. I’ll explain why in my next post.

Finally, a quotation to ponder, and a familiar one at that. From Thomas Jefferson, on the reverse side of the map to the National Treasure:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident,— that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” (Declaration of Independence).

A Happy Coincidence? Or . . . ?

Part 8 of the series “Happy TIME”

Posted at 9:45 p.m. on Tuesday, January 18, 2005

My intention for today’s blogging was to begin the wrap-up part of this series as I talked about the Pandora's box I had opened in my last post. Starting with today’s post, I had planned to reflect upon happiness from a biblical perspective, looking especially at the distinctive contribution of Scripture to the current debate about how we can be happy. But something unexpected happened today that has focused my conversation in a helpful way I had not anticipated. (I'll get back to Pandora's Box tomorrow.)

I began my day with a devotional reading from the Psalms – my usual practice these days (which is not to say I don’t miss sometimes!). Once again I’m working chapter by chapter through the entire book. Having recently completed Psalm 15, today I focused on Psalm 16. You can imagine my surprise when I got to verses 7-11:

I bless the LORD who gives me counsel;

in the night also my heart instructs me.

I keep the LORD always before me;

because he is at my right hand, I shall not be moved.

Therefore my heart is glad, and my soul rejoices;

my body also rests secure.

For you do not give me up to Sheol,

or let your faithful one see the Pit.

You show me the path of life.

In your presence there is fullness of joy;

in your right hand are pleasures forevermore. (italics added)

I’ve read or meditated upon this psalm dozens of times before, but never in the midst of a blog series on happiness. I was startled to discover how this psalm speaks directly to what I was planning to write about today. This must be either a happy coincidence, or a miracle of God’s providence. I’m leaning toward the latter. Of course happiness is a common theme in the Psalms, so my miracle isn’t a huge one. Yet few Psalms are clearer than Psalm 16 about the goodness and nature of true happiness.

So what can we learn about happiness from Psalm 16? Well, first, we see that David, like so many other biblical writers, does put a premium on happiness. Note these phrases: my heart is glad; my soul rejoices; fullness of joy; pleasures forevermore. Clearly these belong in the happiness ballpark.

Yet David speaks of a deeper kind of happiness than we sometimes associate with the word “happiness.” He refers to “fullness of joy,” not just some superficial glee. In fact the “pleasures” of which David speaks are “forevermore” (or as in the NIV, “eternal pleasures”). They are not temporary feelings, like most pleasures.

What stands out most clearly in Psalm 16 is the source of true happiness: not circumstance, not possessions, but the presence and guidance of God:

I bless the LORD who gives me counsel . . .

I keep the LORD always before me . . .

Therefore my heart is glad. . . (7-9)

You show me the path of life.

In your presence there is fullness of joy (11).

David’s joy comes from being with God and from receiving God’s direction.

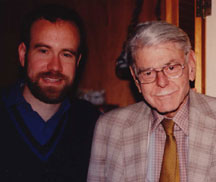

| The way David talks about God reminds me of times I spent with my grandfather. “Poppy” and I must have hung out for thousands of hours during my youth. During much of this time we were in his workshop, where I watched him create wonders out of wood and metal. In time he taught me the tricks of the handyman trade. These were some of the most joyful times of my life. They weren’t exuberantly happy like Christmas morning. But they were times of deep gladness for me, in which I felt secure, valued, and loved. When I think back on those dear times, I can say I treasured Poppy’s presence and guidance. It was great just to be with him. And his instruction was golden. |

|

| |

Here I am with Poppy, about a year before he died. This picture is one of my favorite treasures. Time with Poppy was one of my life's greatest treasures. |

Nevertheless, you may still remain unconvinced that Psalm 16 is really about happiness. Maybe I’m just reading this psalm through the feeling-dominated spectacles of our culture. For an external point of reference, and one that is decidedly not feeling-dominated, I thought I’d see what John Calvin, the 16th century theologian and reformer, had to say about Psalm 16. Here are some excerpts from his commentary on the Psalms:

On verse 9: In this verse the Psalmist commends the inestimable fruit of faith, of which Scripture every where makes mention, in that, by placing us under the protection of God, it makes us not only to live in the enjoyment of mental tranquility, but, what is more, to live joyful and cheerful.

On verse 11: Fulness of joy is contrasted with the evanescent allurements and pleasures of this transitory world, which, after having diverted their miserable votaries for a time, leave them at length unsatisfied, famished, and disappointed. . . . David, therefore, testifies that true and solid joy in which the minds of men may rest will never be found any where else but in God; and that, therefore none but the faithful, who are contented with his grace alone, can be truly and perfectly happy.

So then, if you don’t buy my interpretation of Psalm 16, perhaps one from a highly intellectual Reformed theologian writing five centuries ago will convince you! It seems patently obvious that Psalm 16 commends true happiness, and shows that it is to be found in God, and God alone.

But, having said this, I’ll return to the caveat with which I ended my last post. All of this talk of happiness can open a Pandora’s box. So, barring some unforeseen miracle of providence, tomorrow I will talk about what’s in the box and how we can avoid it.

Opening a Pandora’s Box of Happiness

Part 9 of the series “Happy TIME”

Posted at 9:45 p.m. on Wednesday, January 19, 2005

In my last post I showed how Psalm 16 leads us to the conclusion that happiness is a major concern both of the Psalms and of the Bible as a whole, for that matter. Yet I confessed that making such a point ran the risk of opening up a Pandora’s box of happiness. Now I’ll explain what I mean.

Pandora, if you remember your ancient mythology, was created by the gods as the first woman. She was given a special box (or jar, as a literal translation of the Greek pithos would have it) and told never to open it. But her curiosity got the better of her and she opened the box, thus letting out all of the terrible things that have afflicted humankind ever since (see Hesiod, Works and Days, 80-100).

Keep Pandora in mind for a moment as I offer an obvious observation about contemporary American society. We Americans can be consumed with the search for happiness, especially our own happiness. David Van Biema, in his article “Does God Want Us to Be Happy?” shows that we tend to color our religion with the ink of happiness, whether this reflects its natural colors or not. His cites a fascinating example, in which Dr. Howard Butler “collaborated with the Dalai Lama on a Buddhist primer for non-Buddhists.” Yet they faced the daunting challenge of beginning with Buddha’s first Noble Truth, that life is suffering. So Cutler suggested that they rearrange matters, beginning with the lighter material. “It was very American,” Cutler explains. They gave their book the equally American title: The Art of Happiness. It was a best seller. The Art of Suffering, a more accurate Buddhist title, wouldn’t have made it past the literary agent’s in box. |

|

|

The top painting is by J.W. Waterhouse, who painted this in 1896. The lower painting is a fascinating recent creation by Alex Gross. |

|

So, if I say that the Bible is concerned for our happiness, I may open up a Pandora’s box of self-indulgence. Our culture sharpens our senses to focus on anything related to our happiness, such that we might easily over-emphasize biblical teaching on happiness. As a consequence, we might very well miss the main point of the Bible. Even if God wants me to be happy, that doesn’t mean this is his primary concern for my life. Happiness may instead be a by-product of other things.

Nowhere does the Bible command us to be happy. Yes, the Bible doesn’t tell us to be glum, either. And, yes, Scripture is chock full of commands to rejoice. But biblical rejoicing is less about conjuring up momentary feelings and more about delighting profoundly in God and expressing this through joyful worship.

If God never commands us to be happy, he does, however, tell us to be holy:

The LORD spoke to Moses, saying: Speak to all the congregation of the people of Israel and say to them: You shall be holy, for I the LORD your God am holy. (Leviticus 19:1-2)

Consecrate yourselves therefore, and be holy; for I am the LORD your God. Keep my statutes, and observe them; I am the LORD; I sanctify you. (Leviticus 20:7-8)

Although God often calls his people to holiness, you’ll look in vain for a biblical text that reads, “You shall be happy, for I the LORD your God am happy.”

Being holy means being set apart from the world for God and God’s purposes. It means thinking, feeling, and acting in ways that are different from the world’s ways. Holiness doesn’t require rejecting everything in the world, which would be impossible, at any rate. But it does mean setting aside the ways of this world that are contrary to God. Holiness for contemporary Christians, I would suggest, doesn’t demand that we give up a concern for happiness. But it does mean that we subordinate this concern to many others, like glorifying God, for example, or living holy lives.

There is a connection between holiness and happiness, however.

When God called his people to be holy, he gave them the Law to guide their steps. Though contemporary culture tends to think of law negatively, as that which limits us and restricts our fun, from a biblical perspective the Law leads, not only to holiness, but also to happiness. Take Psalm 1, for example:

Happy (’ashrei) are those who do not follow the advice of the wicked,

or take the path that sinners tread,

or sit in the seat of scoffers;

but their delight [or pleasure] is in the law of the LORD . . . . (Ps 1:1-2)

As Christians, we have been set apart by God for relationship with him through Christ and to serve him in the world. God guides us through his Word and Spirit, both telling us to do and telling us what not to do. As holy (set apart) people we are to live holy lives. Yet this does not lead to some sort of dour, lifeless rigidity. Rather, holy living fosters greater joy. It includes festival and celebration. Yes, it also means refraining from that which God forbids. But this, I noted earlier in this series, actually augments our happiness, according to research reported in TIME magazine. It keeps us from seeking momentary pleasures that end up squandering deeper joy.

Thus by answering the question “Does God Want Us to Be Happy?” in the affirmative, I’m not saying happiness is the chief point of life. Nor am I saying that you get to choose your own happiness. God calls you to holiness, and reveals that true happiness is to be found through holy living. If we keep the call to holiness firmly in mind, then we can talk about happiness without throwing open Pandora’s box so that every demon of self-centeredness and hedonism escapes to ruin our lives.

Does God want us to be happy? Sure. But the way to happiness isn’t found in trying to be happy. Rather it’s found in heeding the clear call of God to be holy, even as God is holy.

The Strangest Part of Biblical Happiness

Part 10 of the series “Happy TIME”

Posted at 9:45 p.m. on Thursday, January 20, 2005

So far I’ve shown that, from a biblical point of view, God does want us to be happy. But God’s version of happiness differs widely from that which is popular today. It doesn’t come from money, or possessions, or sensual experiences. Rather, true happiness comes from being in relationship with God and receiving God’s guidance for living. As Tim Cook wrote in my guestbook (#10), “God doesn't want us to be happy...He wants us to be obedient. He knows, and we can learn, that obedience brings happiness...but it's secondary.” Well put, Tim!

Now I’ll admit that what Tim wrote can sound rather strange in today’s world. But this isn’t the oddest feature of biblical happiness. This most peculiar aspect we find in the Beatitudes when Jesus says,

Happy are those who mourn, for they will be comforted. (Matt 5:4)

Happy are you when people revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven . . . . (Matt 5:11-12)

His point is that we can be happy in the midst of sorrow and persecution because we have the hope of God’s future comfort and reward.

The letter of 1 Peter takes this saying of Jesus and runs with it for a paradoxical touchdown:

For God has reserved a priceless inheritance for his children. It is kept in heaven for you, pure and undefiled, beyond the reach of change and decay. And God, in his mighty power, will protect you until you receive this salvation, because you are trusting him. It will be revealed on the last day for all to see. So be truly glad!There is wonderful joy ahead, even though it is necessary for you to endure many trials for a while. These trials are only to test your faith, to show that it is strong and pure. It is being tested as fire tests and purifies gold—and your faith is far more precious to God than mere gold. So if your faith remains strong after being tried by fiery trials, it will bring you much praise and glory and honor on the day when Jesus Christ is revealed to the whole world. You love him even though you have never seen him. Though you do not see him, you trust him; and even now you are happy with a glorious, inexpressible joy. (1 Peter 1:4-8, NLT, italics added)

Like Jesus, Peter envisions the possibility of present-day happiness in light of a glorious future. This is made all the more astounding by the situation of the people to whom Peter is writing. The recipients are going through difficult times, being persecuted for their faith. Yet in the midst of such difficulties they “are happy with a glorious, inexpressible joy.”

So what’s the strangest part of biblical happiness? It’s the close connection between happiness and suffering. It’s the notion that one can be truly happy even in the midst of suffering. It’s the idea that suffering may even lead one to experience a deeper kind of happiness than if one had not suffered.

Now, having said this, I must warn you not to use this truth to make hurting people feel even worse. Sometimes well-intentioned folk try to help suffering people feel better by telling them to rejoice. And then, when rejoicing doesn’t happen, the well-intentioned folk can even lay a guilt trip on the sufferers, which of course only magnifies their pain.

I don’t believe a person can be exhorted out of pain into rejoicing. Yes, it may be helpful at the right time to remind someone of the blessings of eternity. But joy in the midst of sorrow isn’t something we conjure up by our own strength. It’s a gift of God’s Spirit. Notice what Paul writes in his letter to the Romans: |

|

| |

An icon of Perpetua, an early Christian martyr who, like some many others, experienced joy even in her martyrdom. This icon is by Nicholas Papas. |

We can rejoice, too, when we run into problems and trials, for we know that they are good for us—they help us learn to endure. And endurance develops strength of character in us, and character strengthens our confident expectation of salvation. And this expectation will not disappoint us. For we know how dearly God loves us, because he has given us the Holy Spirit to fill our hearts with his love (5:3-5).

Happiness even in suffering comes, in part, because we can be confident of what lies ahead in God’s future for us. Yet, in addition to this confidence, we also have the love of God that fills our hearts through the Spirit. To put the matter differently, the Holy Spirit helps us to taste now a bit of the joy to come.

If you’ve been reading my blog for the last three weeks, this will sound very familiar. It was a central theme of my “All Things New” series, a reflection on how we can experience God’s newness even in a world devastated by a tsunami.

I’m well aware that what I’ve said about happiness and suffering can sound glib, or even like a bunch of theological mumbo-jumbo. But I don’t mean to be trite or irrelevant. I do understand, however, that what I’m saying – or what the Bible is saying – about happiness is counter-intuitive. Yet so is the gospel of grace, which is centered in God’s coming as a human being to suffer and die for the sake of humanity.

I freely admit, however, that I haven’t begun to plumb the depths of the truth I’m speaking of here, principally because I haven’t experienced horrendous suffering. And, I’ll freely admit, I have no desire to do so, in spite of what I believe about joy and suffering. I am a wimp when it comes to pain. But I have had experiences in my life that help me to understand in some tiny way how rejoicing is possible in the midst of sorrow.

I think, for example, of my father’s memorial service. My dad died when he was only 54. I was 29 at the time. His death was slow and painful as cancer ravaged his body. When he finally died, my family and I felt lots of relief in addition to lots of sorrow. But at his memorial service I felt an altogether new feeling. As I heard words of witness to my dad’s life, as I was reminded of God’s love and the promise of eternal life, and most of all as we sang songs of praise to God, I felt what I can only call joy. It was rather like happiness, only deeper, richer, sadder, and happier. I rejoiced in the gift that my father had been to me, and in the gift of eternal life that was now his. Such joy didn’t erase my sorrow, but it embraced it and in some paradoxical way, even set me free to grieve with greater freedom. Yet I don’t claim any of this as coming from myself. It was a gift of the Spirit, a foretaste of heaven, and a very strange kind of happiness.

If You’re Happy and You Know It Clap Your Hands!

Part 11 of the series “Happy TIME”

Posted at 11:15 p.m. on Friday, January 21, 2005

When I was young, we would sing the children’s song:

If you’re happy and you know it clap your hands.

If you’re happy and you know it clap your hands.

If you’re happy and you know it,

Then your face will surely show it.

If you’re happy and you know it clap your hands.

If you’re not familiar with this song, you can hear it at this link. This was one of those great kids’ songs that allowed for endless variations: If you’re happy and you know it . . . touch your toes . . . say “Amen” . . . shake your head . . . and so forth. It also raised a curious psychological question: Can you be happy and not know it? But such things didn’t bother me when I was young.

The connection of happiness and hand-clapping occurs in Scripture. Psalm 47:1 reads:

Clap your hands, all you peoples;

shout to God with loud songs of joy.

Elsewhere in Scripture nature herself joins in the glad applause:

For you shall go out in joy,

and be led back in peace;

the mountains and the hills before you

shall burst into song,

and all the trees of the field shall clap their hands. (Isaiah 55:12)

These passages point out a distinctive quality of biblical happiness: it is essential to and expressive of worship. From a scriptural perspective, worship and happiness go hand in hand. |

|

| |

Children clapping in worship

|

For a good part of my life I didn’t actually know this. Yes, in my Sunday School classes we learned Psalm 100 (“Make a joyful noise to the Lord”), but the emphasis was put on Habakkuk 2:20: “The LORD is in his holy temple; let all the earth keep silence before him!” Worship was about quietness and reverence, not joyful noises. But throughout the last decades, even we somber Presbyterians have managed to inject a bit of gladness into our worship. I’ve even heard joyful noises and clapping hands in Presbyterian churches. Imagine that!

|

This has happened, in part, because we’ve mixed it up with Christians from other traditions. In my own church in the 90’s, some of our most joyful and expressive worship came when we were led by an African-American gospel choir. Their joyful expressiveness was enough to get my staid, mostly Anglo congregation up on our feet, singing and clapping.

Please don’t misunderstand me. I do believe there is a place for silence and reverence in worship. I have a book coming out in a couple of months that will talk about the need to worship God both through joyful noises and awestruck silence. I’ll have more to say about this later. |

A gospel choir leading worship

|

|

But for now I want to underscore the biblical point that happiness should pervade our worship. To put it differently, not only does God want us to be happy, but also he wants us to share our joy with him. God wants to partake of our joy, to join in our celebration. God, you see, is also a rejoicing God. If you don’t believe me on this, consider this astounding passage from the Old Testament prophet Zephaniah:

Sing aloud, O daughter Zion;

shout, O Israel!

Rejoice and exult with all your heart,

O daughter Jerusalem!

The LORD has take away the judgments against you . . . .

On that day it shall be said to Jerusalem:

Do not fear, O Zion;

do not let your hands grow weak.

The LORD, your god, is in your midst,

a warrior who gives victory;

he will rejoice over you with gladness,

he will renew you in his love;

he will exult over you with loud singing

as on a day of festival. (Zephaniah 3:14-18)

On the basis of this text we could say that God wants us to be happy because he wants us to be like him! And as we celebrate God in joyful worship, he rejoices over us as well. What a stunning thought!

As one who didn’t begin life associating worship with happiness, I do so now. In fact some of my most joyful moments are in worship services at my church. They come when I see a couple that had been on verge of divorce now restored in their marriage and holding hands in church. They come when I listen to God’s truth sung in a marvelous anthem or a stirring praise song. They come when I see a man for whom I have prayed for over ten years take his first communion as a new believer. They come when I confess my sins and realize that God has truly forgiven me. With David the psalmist I profess:

Happy are those whose transgression is forgiven,

whose sin is covered. (Psalm 32:1).

A couple of years ago my church put together a “Basics for Worship” statement, a document that summarizes our basic convictions about worship. I want to close this post by quoting one section of that statement. It’s called “Worship and the Gospel”:

Christian worship responds to God's grace given through Jesus Christ, who died on the cross and was raised from the dead so that we might experience eternal life. In worship we proclaim, celebrate, and dramatize the gospel of grace. We remind each other of what God has done in Jesus Christ and we invite all people to share in God's grace through faith in Christ. Because we have been saved by grace, we worship with joy.

Now there’s a reason for clapping!

Home

|