| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

God's Guidance for Christians in Conflict

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2005 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com . Thank you.

God's Guidance for Christians in Conflict: Introduction

Part 1 of the series "God's Guidance for Christians in Conflict"

Post for Thursday, April 21, 2005

In the last couple of days I've received several e-mails from friends who are all connected to one local church. Some are active members and leaders of this church; others are now estranged from it, having left with feelings of great disappointment in the church's leadership. I'm getting all of these e-mails because this church is experiencing major conflict, the sort of controversy that can cripple, divide, or even kill a church (not the Church of Jesus Christ, mind you, but one individual church). Some of my friends are simply informing me about what's happening. Others have been seeking my advice for how they should act in such a delicate situation.

As I watch what's going on, my heart is heavy. I see a wonderful fellowship fractured by discord and disagreement. I see brothers and sisters in Christ hurting each other with unkind words and unwise actions. I see distraction from the church's primary calling. I see threats and counter-threats. All of this makes me profoundly sad.

I am in no position to have well-informed opinions on the issues that are dividing this church. I do have plenty of opinions about such things, of course, but they are not well enough informed to be worth sharing in this blog. So I'll keep these opinions to myself. The last thing I want to do is open my big mouth (or my big blog) and make matters worse for this hurting church.

Ironically, I have friends on all sides of the issues. And these friends, though differing on several matters, share the most important things in common, including: a profound commitment to Jesus Christ; a deep love for Christ's church in general and for their church in particular; and an honest desire for their church to be healthy and God-honoring. Yet, at the moment, this solid common ground of unity is being shaken by the tremors of church conflict. Hence my heavy heart. |

|

In light of what's going on in my friends' church, I've decided to write a blogging series on what to do when you're involved in church conflict. Though this series will involve biblical and theological concepts, it will be quite practical. I want to focus on what Christians can and should actually do when disagreement rears its ugly head within their church. And, I'm sad to say, this will happen in the experience of most Christians at one time or another. Church conflict has been with us since the beginning of the Christian era, and it won't go away until Christ sets all things right in the age to come.

I'm hoping, quite frankly, that a few of my friends at the hurting church might read what I'm writing and benefit from it. But, even if this doesn't happen, I pray that this series will be of value to others. Honestly, though my church is in a season of relative harmony these days, I'm well aware that conflict may be right around the corner. We've been there before and, given the twin realities of sin and Satan, we'll be there again. So maybe there will be a time when this blog series will be relevant in my own ministry, though I rather hope not.

Our Starting Point

Where should we start if we're seeking God's guidance for conflict among Christians? Here's where my Protestant convictions come strongly into play. We should start with Scripture, with God's inspired Word. Now this is always a good starting point, the best there is, in fact. But in times of conflict it's even more essential that we begin with and cling to biblical teaching. There are several reasons why.

First, in times of conflict our natural human emotions can often try to dictate our behavior. We feel anger and want to lash out. We feel fear and want to defend or attack. We feel wronged and want to get revenge. And so forth and so on. Yet if we allow our emotions to guide our behavior, inevitably we'll simply make matters worse. On the contrary, if we tenaciously hang onto biblical teaching, we'll find the power to act rightly even when our feelings try to drag us in the opposite direction. I can't tell you how many times I've found myself wanting to get even with people who have wronged me. Yet by holding on for dear life to God's Word I've managed to avoid behaviors that would have been both sinful and self-defeating.

Second, in times of conflict we must stand solidly upon Scripture because God's ways of dealing with conflict are often very different from the world's ways. When we're in the midst of some church battle, we're tempted to adopt the ways of the world. Chief among these ways is the desire to win, often mostly for the sake of winning. We can also be tempted to use human schemes to defeat our opponents. We spin like we're in the middle of a dirty political campaign. We rally the troops. We get out the vote. We defend ourselves. We play the victim. We undermine our opponents. We conveniently ignore facts that don't support our side. We hold grudges, and so forth and so on. It will feel natural to us to use the world's ways to win church battles, and, as we do, the world around us will cheer. But rarely are these the ways of a God who says to us, "For my thoughts are not your thoughts, nor are your ways my ways" (Isaiah 55:8). The world doesn't have much room for One who tells us to turn the other cheek, who calls us to forgive seventy times seven, and who urges us to imitate His humble, self-sacrificial servanthood. So we need the Bible to show us different ways to operate in times of conflict: the ways of peace, the ways of the gospel, the ways of Jesus Christ.

Third, in times of conflict among Christians we need the Bible as the source both of practical guidance (here's how to act) and of theological insight (here's how to think about God and the church). The biblical combination of ethics and theology helps to shape our thoughts, feelings, and actions. Though this particular blogging series will be fairly practical, it will also be shot through with theology, because that's the way of God's biblical revelation.

Ironically, I hope this series isn't directly relevant to your life, at least not right now. But even if your church is in a blessed season of harmony, you may be able to direct others to the biblical guidance I will convey. Moreover, if you take seriously what I will share with you, you may very well help your church stay out of serious conflict. And, if this doesn't happen and conflict comes, perhaps I will have helped you to be a peacemaker in your own community.

Enough of introduction. In my next post I'll examine one of the most important of all biblical passages for discerning God's guidance in the midst of conflict.

Let God Speak to You Through His Word

Part 2 of the series "God's Guidance for Christians in Conflict"

Post for Friday, April 22, 2005

Yesterday I began a new series called "God's Guidance of Christians in Conflict." The immediate impetus for this series is a serious church conflict in a congregation where I have many friends – friends on both sides of the most divisive issue, I might add. So I'm writing this series in the hope that I might help my friends find God's guidance in this difficult time. But, beyond this, I want to gather together some biblical insights that will help others as well.

Today I want to draw your attention to one of the most important passages for discerning God's guidance for Christians in conflict. It comes from the second chapter of Paul's letter to the Philippians:

If then there is any encouragement in Christ, any consolation from love, any sharing in the Spirit, any compassion and sympathy, make my joy complete: be of the same mind, having the same love, being in full accord and of one mind. Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility regard others as better than yourselves. Let each of you look not to your own interests, but to the interests of others. Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus,

who, though he was in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be exploited,

but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

being born in human likeness.

And being found in human form,

he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross.

Therefore God also highly exalted him

and gave him the name

that is above every name,

so that at the name of Jesus

every knee should bend,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,

and every tongue should confess

that Jesus Christ is Lord,

to the glory of God the Father.

(Philippians 2:1-11) |

|

| |

A crucifix from the Cathedral in Barcelona, Spain.

|

If you're in the midst of conflict with other Christians, let me urge you to do the following. And, frankly, you might well want to do this even if you're not in a conflictual place right now.

1. Ask the Lord to speak to you through this section of His Word and through the ministry of the Holy Spirit.

2. Prayerfully, slowly read this passage. Read it at least three times. If possible, read it aloud. Let each word sink in. Be attentive to what God is saying to you personally. (Note: Don't start applying this text to others and focus on what they need to do. Let the Lord speak to you about you.)

3. As God convicts you, go with it. Talk to Him about it. Confess if you need to. Ask for His help to obey if you need to. Take time to talk with the Lord about how this passage should impact your life.

4. If you are able to do so, share with at least one other believer what God has been saying to you through Philippians 2. Be open to encouragement and or correction from this believer (or these believers). Ask them to pray for you as you move to the next step.

5. Act upon what God has said to you through this passage. Be a doer of the Word, not a hearer only (James 1:22). You may find it very hard to do what God wants you to do. Be assured: He will provide the strength you need if you depend on Him.

I'm going to stop now. Yes, I have a few things I want to say about this passage. But right now I think I should get my words out of the way. What you need most of all is the Word of God, brought to life by the Spirit of God. My reflections will come in due time, and that time will be tomorrow. But I truly believe that if you're experiencing conflict with other Christians, and if you take time to prayerfully meditate upon this section of Scripture, and if your heart is open to God, then He will guide you to do what is right and honoring to Him. You will begin to see the conflict you're in from God's perspective. And you'll begin to see how you can be an agent of God's peace at this time.

May the peace of Christ be with you . . . really!

Having the Mind of Christ

Part 3 of the series "God's Guidance for Christians in Conflict"

Post for Saturday, April 23, 2005

Yesterday I encouraged you to read Philippians 2:1-11 slowly and prayerfully. Today I'd like to highlight a few features of this astounding text.

If you're in the middle of a conflict with other Christians, however, you might not like this passage very much. Your gut instinct is to win the battle, to be vindicated, to prevail over your opponents. But this text speaks of being agreeable, humble, and considering others as better than yourself. If you're like me when I'm duking it out with my brothers and sisters in Christ, this is not what you want to hear. You'd probably prefer that I had sent you to Psalm 58:8, in which David prayed about his enemies: "Let them be like the snail that dissolves into slime." But, like it or not, if you're a follower of Christ, you've got to deal with Philippians 2:1-11. More to the point, you're stuck with the compelling and challenging example of Jesus himself.

Philippians 2 begins with a series of ethical injunctions that could be paraphrased: agree with each other; love each other; be humble; care more for the concerns others than for your own concerns. These imperatives are summarized in verse five: "Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus." In a nutshell, we are to think as Jesus thought.

Paul doesn't leave it up to us to decide what it means to think like Jesus. We don't get to pick and choose from the gospel stories or to make up our own version of what constitutes the mind of Christ. Rather, Paul shows us quite clearly in verses 6-8 what it means to think like Jesus:

[Christ Jesus], though he was in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be exploited,

but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

being born in human likeness.

And being found in human form,

he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross.

This is a tricky text for a variety of reasons. For one thing, the language is rather unusual for Paul and therefore difficult to interpret. This fact, combined with the poetic structure of the passage, has led many scholars to propose that Paul is quoting an early Christian hymn, something he did not write. This explains the uniqueness of the language. But it's also possible that Paul composed this poetic text when writing to the Philippians. In either case, it's not easy to determine the precise nuance of every word here, even though the big picture is fairly clear.

What is this big picture? It's an image of Christ's active humility. It's a portrait of one who was fully equal to God the Father, but who, nevertheless, chose to take on the form of a slave by becoming human. Moreover, this passage paints a shocking picture of a divine being who not only became human, but also chose to die a most humiliating and painful death by crucifixion. One cannot imagine a more startling and unsettling image of humility and self-sacrifice.

Throughout the ages commentators and scholars have seen Philippians 2 as a theological reflection on Jesus's washing of the disciples' feet in John 13. In this gospel text Jesus literally humbled himself, doing that which a literal slave would ordinarily have done. He did this to teach his disciples how they were to love each other, in anticipation of his ultimate act of love on the cross. In Philippians 2 Paul uses the image of the humble, self-sacrificing, serving, crucified Christ to teach the Philippians believers how they ought to treat each other.

Philippians 2 raises all sorts of tantalizing theological questions about the nature of Christ. In what way was he equal to God? In what sense did he empty himself? And so on. Yet Paul doesn't deal with such questions in this text. Rather he uses the image of the humble Christ to show the Philippians – and by extension, to show us – how we ought to relate to each other. We're called to imitate Christ, not in any way we please, but specifically with respect to his humbling, self-giving, sacrificial action. |

|

| |

A fresco by Giotto, depicting Jesus washing the feet of the disciples (c. 1305).

|

This isn't easy to do! It's hard to do what this text requires in the best of times. Even when I'm getting along well with others I still find it natural to put my self-interest first. But, when you're in the midst of conflict with other believers, doing what Philippians 2 requires is more than hard. It's impossible . . . without God, that is. It challenges the very fiber of our being. It calls us to counter-intuitive and counter-cultural humility. And we're just not wired to do this sort of thing apart from divine help.

But God's help is available to us in several ways. These are highlighted in verse 1 of our text, which I'd paraphrase in the following way: "If there is any encouragement in Christ – which, of course, there is – any empowering comfort in Christ's love – which, of course, there is – any partnership with the Holy Spirit – which, of course, there is – [agree together, love each other, etc.]." Here's what God provides to help us do the impossible:

1. Encouragement in Christ -- The teaching and example of Jesus himself empower us to do what otherwise we could not do.

2. Empowering Comfort in Christ's love – The more we experience Christ's love for us, the more we will be enabled to love with this same sort of love. The more we are secure in Christ's love, the more we will be able to take the risk of loving, not only our neighbors, but also our enemies.

3. Partnership with the Holy Spirit – When we put our faith in Christ, the very Spirit of God comes to dwell in us, empowering us with the same power that raised Jesus from the dead. The Spirit is in the process of making us more and more like Christ.

Years ago I was the pastor in charge of a group of leaders. This group was in the midst of a nasty conflict. One of the leaders was especially vicious in the way she was treating another leader. I challenged her to think about what Jesus would do. Her response, shouted passionately, was: "I don't care what Jesus would do! I'm not Jesus!" I was tempted to say, "Well, that's fairly obvious," but, by God's grace, I didn't. Instead I reminded her of the good news that God, through the Spirit, helps us to be like Christ even when our natural capabilities are inadequate. The confession "I'm not Jesus!" is actually a great place for a Christian to start. But it's not a place to end. Once we realize our own inadequacies, we're ready to trust God more completely, and to discover that we can do all things through Christ who makes us strong (Philippians 4:13).

So, when you're in the middle of conflict, ask yourself: "What would it be for me to have the mind of Christ here?" And don't just ask yourself, ask Christ Himself through prayer: "Lord, how would you think in this circumstance? How can I imitate your example of selflessness and humility now?" The more you look to Jesus, the more you'll discover how you're to act in controversial and divisive circumstances. The more you depend upon Jesus, the more you'll find unexpected strength to be agreeable, loving, humble, other-directed, and Christ-like.

Corinth: The Paradigm of Christian Conflict

Part 4 of the series "God's Guidance for Christians in Conflict"

Post for Monday, April 25, 2005

If you consider the issue of Christians in conflict from a New Testament perspective, you will quickly focus on Corinth. No church in Scripture is more ridden with disagreement and controversy than the Corinthian church, which explains, in part why so much of the New Testament focuses on Corinth. It took the Apostle Paul multiple visits and letters, two of which we have in the New Testament, to sort out the problems in this church.

The letter we know as 1 Corinthians, which is actually Paul's second letter (see 1 Cor 5:9), was written primarily because the Christians in Corinth weren't getting alone with each other. After greeting the letter recipients at the beginning of the first chapter, Paul explains what he has learned about this church:

For it has been reported to me by Chloe's people that there are quarrels among you, my brothers and sisters. What I mean is that each of you says, "I belong to Paul, "or "I belong to Apollos," or "I belong to Cephas, " or "I belong to Christ." (1:11-12)

The Greek word translated here as "quarrel" can also mean "argument" or "strife." Paul uses this same word again in the third chapter of his letter: "For as long as there is jealous and quarreling [eris] among you, are you not of the flesh . . . ?" (3:3). The Corinthian church is being torn apart, not by one single controversy, but by multiple conflicts and tensions.

As we read through 1 Corinthians we can compile as list of these divisive issues. They include:

• Over-identification with one or another Christian leader.

|

|

| |

Ancient Corinth as it appears today. |

• Too much pride in one's own spirituality.

• Sexual immorality.

• Suing fellow Christians in court.

• Prostitution.

• Marriage and divorce.

• Participating in the worship of idols.

• Dressing immodestly in the church gatherings.

• Selfishness in church gatherings.

• Interrupting the gatherings with ecstatic utterances.

Beneath this plethora of issues lay the challenge of working out the Christian life in a non-Christian culture. When some of the people in Corinth put their faith in Jesus, naturally enough they brought along their cultural baggage, including prior experiences in paganism. For example, since it was commonplace for wealthier members of Corinthian society to eat in pagan temples, the privileged few in the Christian community continued to do what came naturally. Yet this scandalized other Christians, especially those who did not have the financial means to eat in temples and who, therefore, considered all temple visitation to be the worship of idols.

In my next post, and in several to follow, I will summarize Paul's response to the conflicts in Corinth. As promised, I will draw practical conclusions as well as make some historical and theological observations.

For now, however, I simply want to note that conflict is a normal part of Christian experience. I'm not happy about this, of course. But it is a fact. Sometimes I've heard people idealize the period of the early church: "Oh, if I could only be back in time of the apostles it would be great. Then the church wouldn't be in such as mess as it is today." Yet, if you go back and read the New Testament carefully, especially the letters of Paul or the letters in Revelation 2-3 to the seven churches in Asia Minor, you realize that the church has experienced conflict from the get go. This fact encourages us not to be surprised when we face conflict today. We should be ready to see it in God's terms and to follow God's guidance for how to resolve it.

Whose Church Is It?

Part 5 of the series "God's Guidance for Christians in Conflict"

Post for Tuesday, April 26, 2005

In my last post I set up the first-century Corinthian church as a paradigm of a church in conflict. The letter we know as 1 Corinthians is the effort of the Apostle Paul to resolve the controversies that were plaguing this early Christian community.

Before we get into some of the specifics of this effort, however, we should look at how Paul addresses the Corinthians at the beginning of his letter. He writes to: "the church of God that is in Corinth." "Church" translates the Greek word ekklesia, which meant "gathering" or "assembly," and referred in particular to the gathering of voting citizens in Corinth. Paul wasn't writing to the "ekklesia of Corinth," a phrase that would easily have been misunderstood. Instead, he addressed his letter to the "ekklesia of God that is in Corinth."

By referring to the Corinthian church as the church "of God," Paul is doing more than distinguishing it from the civic voting assembly, however. He is also letting the Corinthians know who "owns" the gathering of Christians in Corinth. In a phrase: God does. The Christians are not simply one more religious club formed and guided by its members, of which there were many in first-century Corinth. Rather, the Corinthian assembly belongs to God in some strong sense. (Later in the letter Paul will add that the bodies of the individual Corinthians also belong to the Lord.)

Paul reiterates this point at the conclusion of his opening address: "God is faithful; by him you were called into the fellowship of his Son, Jesus Christ our Lord" (1:9, emphasis added). Notice, first of all, that the Corinthian believers aren't in the fellowship because they chose to join. From a theological point of view, they "were called" by God into the fellowship. They are members of the Corinthian church by God's choice and invitation. Moreover, they belong not merely to a human institution, but to a fellowship that has been founded by and is the property of the very Son of God.

Twice in his opening address to the Corinthians Paul emphasizes the fact that their gathering is not their own. It belongs to God the Father and to the Son of God. Later Paul will explain that the church comes into existence through the work of the Spirit of God (see 12:12-13). This is a fundamental truth about the church, and one Paul emphasizes intentionally because it relates to the problem of conflict among Christians. |

|

| |

This may well be the exact place where Paul stood in Corinth to make his defense of his faith. In the background is the Acrocorinth, the mountain that towers over the old city.

|

To relate Paul's point to the situation of conflict among Christians today, let me say this: when you're caught up in a disagreement with other believers, you need to remember whose you are. You belong to God through Jesus Christ. This is true of you personally and also of the church. Whatever else it may be, the church is the church of God: the church that comes from God, is governed by God, and belongs to God.

If you're in a fight with other believers that relates to a particular church, one of the first things you need to remember is that the church is not yours. It doesn't belong to you. It doesn't belong to the people who are on your side. It doesn't belong to the majority of the members. It doesn't belong to the founding members or their descendents. It doesn't belong to the big givers. It doesn't belong to the pastor, or the elders, or even the denomination (if there is one). Your individual church belongs to the triune God. Period. Every other "ownership" is really just a loan.

This basic truth makes a huge difference in the way we think and act with respect to the church, especially in times of conflict. For example:

• If we truly believe that the church belongs to God, then we'll be more committed to finding God's solution to our conflicts than making sure that our side wins.

• If we truly believe that the church belongs to God, then we'll be quick to admit that our personal ideas about what should happen in the church may very well be wrong. Only one opinion really matters, the opinion that belongs to God.

• If we truly believe that the church belongs to God, then we'll realize that the church is not to be trifled with. The church is not first of all a vehicle for my self-expression, or professional security, or enjoyment, or whatever. It is, first and foremost, a vehicle for God's glory. The church exists to do God's bidding, to represent God's kingdom, and to bring praise to God.

I can't emphasize enough how important it is for us to remember to whom the church belongs and, for that matter, to whom we belong. When I've been in the middle of a passionate argument with my elders, for example, one of the best things we've done is to stop and pray. As we come before God, we remember that we're on holy ground. We relinquish our desire to control God's church and submit ourselves to His will. Before the majesty of God, we humble ourselves and share together in common humility. Such an experience of God's sovereignty doesn't magically take away our disagreements, but it does put them in a completely different light. Antagonists vying for ownership of the church become fellow seekers for the will of the One who truly owns the church. Winning no longer matters, except for the victory of God.

This process that I've just described has happened several times throughout my ministry, though it usually doesn't flow as quickly or smoothly as the last paragraph would imply. Nevertheless, I've seen the recognition that the church is God's church transform hearts, including my own. So, one of the most important things we can do if we're in the middle of church conflict is to step back and remember – really remember – that the church belongs to the triune God.

What is the Church?

Part 6 of the series "God's Guidance for Christians in Conflict"

Post for Wednesday, April 27, 2005

In my last post I worked with the question: "Whose church is it?" The answer from 1 Corinthians is clear. The church is God's church. The church is the creation and "property" of the triune God. Acknowledging this means that when we're in the midst of church conflict, we must seek God's will for God's church above all.

Today I want to ask a related "big question": What is the church? What is this entity that belongs to God?

On the simplest level, a church is a gathering of people who belong to God through faith in Jesus Christ. Wherever Christians come together in Christ, there is a church. But this is just the beginning. In 1 Corinthians 3 Paul speaks of the church in striking and surprising language:

Do you not know that you are God's temple and that God's Spirit dwells in you? If anyone destroys God's temple, God will destroy that person. For God's temple is holy, and you are that temple. (3:16-17)

For years I read this passage as speaking about me as an individual Christian. A parallel text in 1 Corinthians 6 does indeed speak of the body of the Christian person as a temple for God's Spirit (6:19). But the emphasis in chapter 3 is different. Here the temple of God is the church, the gathered fellowship of believers.

The context in 1 Corinthians 3 makes it clear that Paul is not focusing on individual believers when he says "you are God's temple." In verse 9, the Corinthian church is "God's building" (3:9). Those who labor as church-planters are in the construction business, so to speak (3:10-15). So when we come to verse 16, we know that the temple of which Paul speaks is not the individual believer but the assembly of believers. The verse might be paraphrased: "Do you now know that you folks [plural in Greek] are God's temple and that God's Spirit dwells among you?"

This interpretation is confirmed in verse 17, which warns the Corinthians against destroying God's temple. The first three chapters of 1 Corinthians have to do, not with threats to individual believers, but to the threat of division in the church at Corinth. So when Paul says, "If anyone destroys God's temple," he's referring to the church of God in Corinth, which is at risk because of the conflicts in the church. |

|

| |

The columns in the center of this picture are what's left of the Corinthians temple of the Greek god Apollo.

|

Part of what makes the church so special is the presence of God's Spirit. When believers gather together, God is with them through His Spirit. The power of God is available so the church can be strengthened. Paul will have much more to say about this in chapters 12-14.

From the mere fact that the church is God's temple, you'd naturally conclude that it ought to be treated with reverence and supreme care. But in case you missed that implication, Paul adds: "If anyone destroys God's temple, God will destroy that person" (3:17). Now that's a threat to take notice of, don't you think? Before you start trifling with the church of God, you'd better realize what you're doing.

Sometimes, especially in the heat of church conflict, people can forget what they're dealing with. They easily think of the church in human terms. I know pastors who have seemed almost willing to destroy a particular church in order to defend their reputation or career. How sad this is! And, given the threat of 1 Corinthians 3:17, how ill advised.

On the contrary, I have seen church leaders sacrifice their advantage for the sake of God's church. A friend of mine was pastoring a solid and growing church when a faction that didn't like his leadership tried to force him out. As he prayed about what was best for God's temple, my friend decided that it would be best if he resigned. Though he felt sure that he could defeat his foes, he also believed that this would seriously damage the church. His career, his income, his reputation . . . none of these mattered as much as the church he loved so much. So he resigned.

I'm not suggesting that every embattled pastor should quit. But I am suggesting that every one of us, especially if we're in the midst of church conflict, should realize, not only that the church belongs to God, but also that it is His temple, the dwelling place of his Spirit. With this in mind, we will do everything in our power both to honor and to protect the church, even if it involves self-sacrifice.

So, if you're in the midst of church conflict, step back from the issues long enough to remember what it is you're dealing with. Are you thinking of your church as the temple of God? Are you doing everything you can to protect and care for God's temple?

How to Think About Christian Leaders?

Part 7 of the series "God's Guidance for Christians in Conflict"

Post for Thursday, April 28, 2005

Every once in a while I'll hear somebody refer to Irvine Presbyterian Church, where I serve as pastor, as "Mark's church." This grates on my soul like fingernails on a spiritual blackboard. Really. It gives me the willies. Now I understand that "Mark's church" is really just shorthand for "the church where Mark is the pastor." But I've seen cases where churches are so identified with the pastor that things are way out of balance. A church that belongs to God ends up being spoken of as the personal property of some individual. The identity of pastor and church are so intertwined that it's almost impossible to think of them as distinct. That which exists for the sake and glory of Christ ends up a virtual personality cult, with the pastor as the dominant star. So, when somebody calls Irvine Presbyterian Church "Mark's church," my warnings lights flash like Las Vegas at night.

The tendency of Christians to over-identify with their leaders is an old one. In fact, it goes right back to the earliest years of the church. In the letter we know as 1 Corinthians, Paul gets right to the point after his opening address:

Now I appeal to you, brothers and sisters, by the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that all of you be in agreement and that there be no divisions among you, but that you be united in the same mind and the same purpose. For it has been reported to me by Chloe's people that there are quarrels among you, my brothers and sisters. What I mean is that each of you says, "I belong to Paul," or "I belong to Apollos," or "I belong to Cephas," or "I belong to Christ." (1:10-12)

|

|

| |

This is not "my church" in two ways. First, it is not really Irvine Presbyterian Church, but only the sanctuary in which Irvine Presbyterian Church worships. Second, this building and the people who gather within it aren't mine, but God's. |

Fundamental to the divisions and disagreements in the Corinthian church was the tendency for the different "parties" to identify with some Christian leader over and against the others. It's easy to understand how this could happen, especially when you consider that in some of the pagan mystery religions the person who guided you into the mysteries held a special place in your heart.

Of course love and appreciation for Christians leaders is a fine thing. But when this love and appreciation becomes divisive or idolatrous, then we have a real problem. In Corinth, the different "leader parties" were splitting the church, with people claiming allegiance to their particular hero rather than embracing the whole church of Jesus Christ.

In 1 Corinthians 3 Paul seeks to set the Corinthians right by helping them to have a right understanding of Christian leadership:

What then is Apollos? What is Paul? Servants through whom you came to believe, as the Lord assigned to each. I planted, Apollos watered, but God gave the growth. So neither the one who plants nor the one who waters is anything, but only God who gives the growth. The one who plants and the one who waters have a common purpose, and each will receive wages according to the labor of each. For we are God’s servants, working together; you are God’s field, God’s building. (3:5-9)

It seems that the Corinthians were divided especially into the group that supported Paul and the group that identified with Apollos, a more articulate preacher and one who might have had greater appeal among the more educated and wealthier Corinthians. Yet in their devotion to a human leader, the Corinthians are missing the point. Both Paul and Apollos are equally servants of God though they may have different functions. Moreover, they share in the common purpose of building a church for God's purposes. Yet the main point Paul makes is that the servants aren't the main thing at all. God is the main thing. God is the Master of the servants. God is the only one who can cause the church to grow. God is the owner of the church, whether seen as a field or a building.

Paul wraps up his argument in verse 21 with a simple imperative: "So let no one boast about human leaders." Though appreciation of leaders is fine, this must not run over into bragging or anything that would divide the church.

Here is a measure for determining the health of leadership in a church: How do the members talk about the leaders? Are they drawing up sides for and or against their leaders? Do they pit some leaders against others? Or do they see all leaders as servants of the One who really matters?

As a pastor, I freely confess how easy it is for me to get too entangled with the church I serve. I can also begin to think of Irvine Presbyterian Church as "my church." I can even think that I am somehow necessary to this church. God forgive me for such pride! Though God has called me to the Irvine church and though He is blessing my ministry there, I'm not in any way essential. God could take care of this church just fine without me. And he could raise up another pastor who could do a better job than I am.

When the church is in the midst of conflict, and especially when a pastor is a point person in that conflict, it's even more difficult for the pastor to have a godly perspective on the church. I know this from personal experience. About ten years ago I was in the midst of the hardest time in my ministry. I had an associate pastor I'll call Shirley with whom I was having many conflicts. From my point of view, she was not fulfilling her job description in many, many ways. From her point of view, I was being imperious and unsupportive. Though I tried everything I could think of to make things work out, they were going south faster than a goose in November.

During this time, Shirley began to lobby the troops on her side. She complained about how I was mistreating her. She would visit shut-ins and tell them I was getting ready to fire her (which wasn't true). She was clearly trying to divide the church, and was doing a fine job of it. I must confess that I was sorely tempted to join the game and beat her at it. I wanted to get people on my side. I wanted people to know the truth and defend me. The church started to become all about me, . . . me, me, me. We were going the way of the splintered Corinthian church.

Everything came to a head at a meeting of our congregation. This was by far the toughest meeting I've ever been a part of. The elders of the church were recommending that we dismiss Shirley as our pastor. In the congregational debate, many people chewed me out for what they perceive to be my management flaws. These were people who believed they knew the truth because they had heard it from Shirley. The temptation to divide and conquer the church was huge for me. But, by God's grace and following the counsel of my fellow leaders, I didn't do it. I took my licks, even ones I didn't deserve. I owned my failures and tried to listen to what people were saying to me. Frankly, it was excruciating. But I sensed that my job as pastor was to help the church be unified in Christ, not divided in order to defend me. Many of my supporters sensed the same. Though they could have risen to my defense, they realized that it was not the time to do so. Wisely, they remained quiet, and so avoided a fight that could have deeply wounded our church.

The congregation did, in the end, vote to dismiss Shirley. I left feeling, not vindicated, but ashamed and exhausted. Several friends gathered around to encourage me. But I still felt as if I had been taken to the congregational woodshed for a beating.

In the aftermath of that meeting, only a couple of people left our church, much to my surprise. In time, many of those who had scolded me actually came to apologize. One man said, "It was only later that I learned some of what had really happened with Shirley. I'm sorry for the things I said to you."

But the greatest result of that whole debacle was not that I was somehow more highly regarded or more beloved or whatever. It was that our people ended up, truly, more united in Christ. I can't explain how this happened, exactly, except that it was a work of grace. But I do know that my effort, and the efforts of those who supported me, to focus on Christ and not on me helped move us toward such a positive result. Nevertheless, I still look back on this whole experience, and the congregational meeting in particular, as the hardest time of my ministry. It required that I subordinate myself to a degree I had never done before. It required that I trust in God rather than my abilities to persuade and organize.

If you're caught in a church conflict, watch out for the role of leaders in that conflict. If battle lines and being drawn up around certain personalities, don't let this happen. And if you're a pastor, I'd urge you to remember – as hard as it may be – that you are merely a servant of the Master. Devote yourself to seeking what's best for whole church. Seek to unify rather than divide. Don't let your people choose up sides, even if this game seems to be to your favor. Rather, do all you can do to further the peace and unity of Christ's church. Let the focus be upon Him, with yourself as His servant.

How NOT to Solve Conflicts Among Christians

Part 8 of the series "God's Guidance for Christians in Conflict"

Post for Friday, April 29, 2005

My friend "Jeff" was the pastor of a church near my own. He and I became friends because we shared many of the same challenges as well as the same basic faith in Jesus Christ. I always liked Jeff because he was humble, earnest, and a deeply caring servant of God.

Jeff's church was on the conservative side, both theologically and liturgically. They had hymns and an organ, proudly so. Nevertheless, Jeff wanted to add a few more contemporary touches to the worship services, like praise songs and a more informal time of prayer. Yet even those small interventions angered some of his elders. At the next board meeting there was a big fight, with two or three of the elders denouncing Jeff in demeaning ways. In the end, however, the board voted to sustain what Jeff had done, much to the dismay of the minority that had opposed him.

Two days later while Jeff was sitting in his office at church, he received an ominous looking letter from a legal firm in town. Reading the letter, he was distressed to learn that one of his elders was suing him because of the changes he had made in worship. I can't remember the specific charges, but I do well remember Jeff's great distress over what was happening to him and his church. He just couldn't believe that one of his elders would sue him in civil court over a church matter.

Since Jeff shared his plight with me eight years ago, I've heard other things like this. I've heard of pastors who have threatened to sue members of their church when they felt they were being mistreated. And I've watched with concern as individual churches and denominations rush to secular courts to solve church related property issues. If you've been reading my blog for several months, you may recall my sadness in hearing that the Episcopal Diocese of Los Angeles was bringing suit against three churches that had voted to leave the Diocese in order to associate with the Anglican Church of Uganda.

The problem of Christians using the legal system to deal with conflicts with other believers isn't new. In fact this was one of the problems facing the church in Corinth in the middle of the first century A.D. We learn from 1 Corinthians 6 that one member of the church had some sort of dispute with another member. But rather than work it out within the church, one of the believers sued the other in secular court. This sort of behavior was common among the wealthy members of Corinthian society. Winning in court was usually more a matter of preserving honor than getting a financial settlement. And being held in honor was the highest value among the Corinthian elites.

But the Apostle Paul was not pleased with what was happening in his church. Here's what he writes to the Corinthians: |

|

| |

This is the platform (bema in Greek) where legal disputes in Corinth were publicly adjudicated. This is the place where, in Acts 18, Paul was charged in the presence of the Corinthian proconsul.

|

When you have something against another Christian, why do you file a lawsuit and ask a secular court to decide the matter, instead of taking it to other Christians to decide who is right? Don’t you know that someday we Christians are going to judge the world? And since you are going to judge the world, can’t you decide these little things among yourselves? Don’t you realize that we Christians will judge angels? So you should surely be able to resolve ordinary disagreements here on earth. If you have legal disputes about such matters, why do you go to outside judges who are not respected by the church? I am saying this to shame you. Isn’t there anyone in all the church who is wise enough to decide these arguments? But instead, one Christian sues another—right in front of unbelievers! To have such lawsuits at all is a real defeat for you. Why not just accept the injustice and leave it at that? Why not let yourselves be cheated? But instead, you yourselves are the ones who do wrong and cheat even your own Christian brothers and sisters. (1 Cor 6:1-8, NLT)

What is wrong with Christians suing other Christians in court? First, there should be sufficient wisdom in the church to solve conflicts. Notice that Paul assumes that disputes among Christians are the business of the church. If a Christian brother has a conflict with another brother, that's not a private matter. It's something that impacts the church and is part of the church's rightful concern.

Moreover, for Christians to sue each other in secular court looks terrible to observing unbelievers. It certainly doesn't commend the gospel of Jesus Christ if Christians sue each other. For that matter, the desire to win and get even doesn't reflect the cross of Christ at all. Thus Paul can end his denunciation of Corinthian lawsuits with a rather shocking statement: "To have such lawsuits at all is a real defeat for you. Why not just accept the injustice and leave it at that? Why not let yourselves be cheated?" (6:7).

This may be one of the most counter-cultural statements in all of Scripture. It's not news to anyone that we live in a highly litigious culture. People sue each other right and left for the most trivial things. Of course some lawsuits are necessary or even right. But it's a given in our society that you should not "accept the injustice and leave it at that." Rather, we are taught to press every possible advantage for the sake of gain, even if that means suing a fellow believer in court.

I can just imagine some of the e-mail I'm going to get because of this post. Many of my readers will find what I'm saying downright offensive. Let me emphasize that I'm not saying Christians should never turn to secular courts under any circumstances. There may be times when a church system is so dysfunctional that justice can only be found outside of the church. The tragic case of sexual abuse in the Roman Catholic Church is one such example. But this is nothing we should be proud of or seek to perpetuate. Whatever else, secular lawsuits should be the last resort among Christians. And there are times when a person should simply choose to lose rather than to sue. I think of another pastor friend of mine who was meanly and unjustly fired by his church board. I'm quite sure he could have sued and received compensation. But he chose not to press legal charges because he took 1 Corinthians 6 seriously, and because he didn't want to hurt the church he loved, even though the board of this church had badly injured him. This was a truly Christ-like sacrifice on the part of my friend.

This illustrates the deeper point. We are to imitate the sacrificial example of Jesus Christ. As Jesus teaches, we are to turn the other cheek, to walk the second mile (Matthew 5:39-41). Of course then he models self-giving sacrifice through his death on the cross. Yes, indeed, this sort of thing grates against our own desire for vindication as well as our culture's preoccupation with winning no matter what. But our Lord teaches us both by word and by action how to give up our lives that we might gain true life, eternal life, life in all of its fullness.

So, if you're in a conflict with other Christians, whether it is personal, professional, or ecclesiastical, the way NOT to solve the problem is through suing each other in secular court. (I'm not, by the way, implying that lawyers can't be helpful here. Christians with legal expertise can often assist us in finding just solutions that will keep us from lawsuits. I have seen this very thing happen in my own ministry, where lawyers were extraordinarily helpful in terribly conflicted situations.) Secular lawsuits must not be your first choice, or second, or third. The church, when functioning properly, is the place where true wrongs can and should be adjudicated. Only if the church fails miserably in this duty might it be necessary in some cases for you to get secular legal help.

But before you turn to the civil courts as a last resort, you need to ask the Lord whether he wants you simply to lose. I know this sounds strange. But I think, in light of 1 Corinthians 6 and the example of Jesus Christ, we need to ask the Lord whether he's calling us to lose the fight. Yes, we may lose our pride for a while. Yes, we may lose certain advantages, financial and otherwise. But what we gain, and what the church of Jesus Christ gains, may well be worth the cost.

When my friend Jeff was sued by one of his elders he did not call a lawyer. Instead he did the counter-cultural thing and phoned the elder and said, "I'm not going to fight back because I'm your brother in Christ. We need to work this out in the Lord." When the elder resisted, Jeff got some other elders to talk with the one who had filed suit. They talked with him about 1 Corinthians 6. They called him to act as a follower of Jesus Christ. They offered to help work out reconciliation. To this man's credit, he was finally willing to drop his suit. Though he and Jeff never fully agreed on what worship should be in their church, they were able to live together in Christian love without recourse to lawsuits.

Yes, I know it doesn't always end like this. Often people are not as spiritually mature as Jeff, and they get caught up in a worldly effort to win. And sometimes church leaders aren't willing or able to step up, as were the elders of Jeff's church. But the fact that we Christians fail to do what Scripture calls us to do is no argument for not trying to obey in the first place. We should make every effort to settle our disputes within the context of Christian community. And when this fails, there will be times when God will call us simply to lose rather than to fight on in the courts. Yet in this losing, as counterintuitive as it might seem, there will be a great gain for God's kingdom, and even for our own souls.

Keeping No Record of Wrongs:

A Tribute to My Father and My Mentor

Part 9 of the series "God's Guidance for Christians in Conflict"

Post for Saturday, April 30, 2005

Today is my father's 73rd birthday. Yet, like the last 18 birthdays, we'll be celebrating this one without his physical presence, since he went home to be with the Lord in 1986.

As you can well imagine, I've been thinking lots about my dad recently. How I wish I could talk with him, tell him about my life today, and watch him play with his grandchildren. There's so much I'd like to ask him, so much I didn't even know to ask him about twenty years ago. One of those questions has to do with his experience of disagreements in church, specifically disagreements with Senior Pastors.

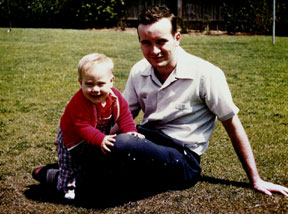

Let me supply a little background for this conversation. From the time I was seven years old onward, my family was actively involved in the First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood. My dad served as a deacon when he was around 30 years old, becoming an elder in the latter part of the decade of the 60's, when he was in his late thirties. |

|

| |

My dad in 1984 |

When he was an elder, I heard talk every now and then of my dad doing something scandalous at the meetings of the board of elders (which we Presbyterians call the Session). His shocking action? Public disagreement with the Senior Pastor. In that day, elders served largely as dark-suited human rubber stamps for the will of the Pastor. Disagreement was almost unheard of, especially in the context of the Session meeting. But my dad actually read the Presbyterian Book of Order, our rules for church governance, in which he discovered that the elders were to have much more say in the life of the church than was typical in those days. By openly speaking his mind even when he differed with the Senior Pastor, my dad was actually being an exemplary elder. Yet, even though he was doing exactly what he was supposed to do according to the Presbyterian rule book, my dad's behavior was, in the Hollywood system of that time, scandalous. (I should say, by the way, that I never once heard my father say anything negative about any Senior Pastor. He did not gossip or negatively influence my experience of church. Everything I know about my dad's disagreements in Session I've learned from others. This is one reason I wish I could talk with him myself. I'd love to hear his side of the story.)

|

My first (and only) experience of my father's disagreeing with "the powers that be" came in 1970. Our Senior Pastor, Dr. Raymond I. Lindquist, had retired, and church leaders had put together a search committee to call a new pastor. This had to be approved in a meeting of the whole congregation, which I, as a young member, was privileged to attend. In that meeting my father stood up and made a long, impassioned speech. He was concerned that the search committee was not representative of the church, having been filled mostly with people over 50. (My dad would have been 38 at that time.) My dad's effort was successful, because the congregation added a couple of younger members to the committee, including, ironically enough, my dad. |

My favorite picture of me and my dad, when we were both quite a bit younger

|

|

I can't say much about his experience on this search committee because he never talked about it, honoring a pledge to keep committee business confidential. But I do remember, near the end of the process, that my father was almost giddy over the person they had found to be our new pastor. When Lloyd John Ogilvie was installed as Senior Pastor in 1972, my father practically glowed. Little did my dad know that this man would have a huge impact on my own life, first as my pastor, then as my mentor.

Yet my father still continued to scandalize the Session by occasionally disagreeing with the Senior Pastor's plans for the church. Somebody once told me of a specific incident that shocked me. Pastor Ogilvie had wanted to replace the church hymnal with a newer version. My dad, who wasn't especially fond of church music, saw that as a poor use of money. He was always fighting for his first love in the church, the children's ministry. So, while the other elders nodded their heads dutifully, my dad spoke up. Apparently he said about the new hymnal proposal, "This is the most asinine thing I've ever heard." Not exactly speaking the truth in love, if you ask me. Well, the vote for the new hymnal was something like 60-1 that night, and you can guess who was the lone "no" vote.

These sorts of incidents in Session weren't regular occurrences, I understand, but they did happen occasionally. As a Senior Pastor myself, I can imagine how bugged Lloyd Ogilvie must have been when my dad, not only opposed his plans, but said they were "asinine." Yet what I know for sure is that my father continued to love and respect Dr. Ogilvie as his pastor, and that Dr. Ogilvie managed to maintain a loving relationship with my father.

I don't know exactly how this was accomplished. (Another question I wish I could ask my dad.) But I have a pretty good idea of what must have happened after meetings in which my dad spoke out, maybe even with inappropriately strong words. My pretty good idea comes from my own experience of Lloyd Ogilvie, under whose leadership I served on the staff of the Hollywood church for seven years.

I also had my moments of disagreement with Lloyd, though I never came close to calling his ideas "asinine," I assure you. But I remember a few very tense moments in staff meetings, times when Lloyd and I had passionate differences. You'd rightly imagine that these were scary times for me, since Lloyd was both my boss and my mentor, not to mention one of my great heroes in life. Yet after these difficult moments – every single time – within a day or so Lloyd would call me on the phone, initiating contact. The purpose of the call wouldn't be to chew me out, but to reconcile. He'd apologize for not listening well to me. I'd apologize for speaking so harshly. He'd hear me out. I'd hear him out. These were precious times. And every one of them came at Lloyd's initiative. (As a Senior Pastor myself I have followed this example maybe a hundred times in my ministry.) So I expect that, after my father had cooled down, Lloyd called him or found a quiet moment to chat. And this, I expect, had much to do with the fact that they remained dear brothers in Christ in spite of some pretty heated disagreements in Session meetings.

I honor the fact that my dad took seriously his responsibility as an elder. It was right for him to speak up when he did, even if his words were sometimes too harsh. This took real courage and integrity. And I honor the fact that Lloyd Ogilvie respected my father's right to speak, didn't write him off, didn't cut him off, but reached out to maintain a loving, healthy relationship with him.

I know for sure that this was the state of their relationship at the end. I know because I witnessed my father's last interaction with Lloyd. It was in late August 1985. Lloyd had just returned from vacation and study leave in Scotland. Though back in the States, he was still officially on vacation, and not doing church business. But he received word that my father was gravely ill with cancer. Lloyd called me at home to confirm my father's situation, and then asked if he could visit him in the hospital. I met Lloyd at the entrance to Huntington Hospital in Pasadena and escorted him through the maze of corridors to my father's room. |

|

| |

Lloyd Ogilvie and me at my installation at Irvine Presbyterian Church in 1991

|

Lloyd spent about fifteen minutes with my dad, who, though he was terribly weak, discouraged, and in pain, brightened considerably when he saw Lloyd enter his room. Their conversation was filled with tenderness, as they shared their hearts for the church, for my family, and for the Lord. Lloyd, aware that this might be his last visit with my dad, thanked him for his leadership and faithfulness to the church. My dad thanked Lloyd for being such a fine pastor and friend. When it became obvious that my father was getting too tired to continue, Lloyd prayed for him. It wasn't some packaged prayer that a pastor pulls out when visiting the sick, but a heartfelt prayer of gratitude for my father, seeking God's healing and comfort, and asking for special mercies for our family. When Lloyd finished praying, he bent down over the bed and gave what was left of my dad a tender embrace. As we left the room I could see the tears in Lloyd's eyes – through the tears in my own.

Before he went back to finish up his vacation, Lloyd took me down to the hospital dining room and bought me a cup of coffee. He asked lots of questions about how I was doing, how my family was doing, etc. etc. By the time I left, I felt as if Lloyd had wrapped my dad and me up in the love of Christ. Of all the gifts Lloyd gave to me as pastor, teacher, and mentor, I think this visit is the most precious of all. And I have thought about it literally hundreds of times as I have sought to imitate Lloyd's genuine, open caring in my own ministry – even for those who have sometimes chewed me out in public meetings.

What impresses me today is the fact that, in spite of many ardent and even angry encounters in Session meetings, in spite of numerous disagreements about church plans, Lloyd Ogilvie and my father managed to maintain a deeply loving relationship as brothers in Christ. My dad did not keep what Scripture calls "a record of wrongs" (1 Corinthians 13:5, NIV), choosing instead to love. And Lloyd Ogilvie, who must have been pretty upset with my dad on several occasions, didn't keep such a record either. They both put Christ-like love first in their relationship.

I should add, by the way, the Lloyd never once insinuated to me anything negative about my father or his manner of disagreement. It doesn't take too much imagination for me, as a Senior Pastor, to figure out what Lloyd must have felt sometimes. Only once did Lloyd show his hand just a bit. It was during one of the reconciling phone calls. Lloyd and I had worked through our differences and were finishing up. He said something to me like, "Mark, I do appreciate the fact that you are honest with me, even if this gets us into trouble sometimes." I responded, "Well, Lloyd, like father, like son." On the other end of the line I heard, not just a chuckle, but hearty laughter that lasted for several seconds. It was as if Lloyd was saying, "Oh, Mark, if you only knew!" But even then he didn't say one negative word about my dad. My sense is that Lloyd's record of my dad had no wrongs left on it, just the love of Christ.

So, today, on the occasion of my father's birthday, I want to publicly acknowledge the fact that both my father and my mentor chose to love in the mode of 1 Corinthians 13 by keeping no record of wrongs. They didn't let strategic and visionary disagreements break their relationship as brothers in Christ. And they never let their private frustrations spill out into gossip. I hope and pray that I can be this sort of Christian and this sort of pastor. And I believe that if we all sought to handle our disagreements in this fashion -- with repentance, forgiveness, and reconciliation -- we would be healthier and stronger, both as individual Christians and as the church of Jesus Christ.

In my next post I want to talk a bit more about how love makes a difference when Christians disagree, looking once again to 1 Corinthians.

What Love Is All About: Realism Beyond Romance

Part 10 of the series "God's Guidance for Christians in Conflict"

Post for Monday, May 2, 2005

I'll confess to being a softy when it comes to romantic things. I'm not necessarily good at thinking them up and doing them, mind you, but I'm an appreciative observer. I'm a sucker for a romantic film, even a corny and predictable one. I like violins crooning the background and happy endings.

But, I must confess that I get nervous about too much romance in weddings, of all places. And since I go to lots of weddings, usually with the best seat in the house, I get nervous a lot. Why? Because I've seen too many wonderfully romantic weddings end in tragedy, to be completely frank. Just over a year ago I participated in one of the most beautiful and elegant weddings I'd ever seen. It was absolutely wonderful, except for the tiny little problem that the couple I married is no longer married today. That's a big oops, and a very sad one.

I also get nervous over too much romance, maybe it's better to say idealism, when it comes to the church. I often hear people talk about some new church they've found – even the church I pastor – in utterly glowing terms: loving fellowship, inspired worship, fantastic preaching, etc. etc. Though I'm glad they've found such a congregation, I worry that too much idealism can lead to all sorts of disappointment and hurt. No matter how wonderful a church may be, it's still full of real people who, though forgiven, aren't perfect. And in such a fellowship conflict is inevitable. |

|

| |

One of the most romantic moments from arguably the most romantic wedding of the last fifty years, between Prince Charles and Lady Di. Such romance didn't guarantee a happy marriage, did it?

|

Years ago when I was an associate pastor at the First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood, I was coaching a team of leaders that was experiencing lots of disagreement. One of the women on the team became exasperated and blurted out: "What's wrong with this group? I thought we were supposed to be a family!" My response was: "Yes. That's exactly the problem. How many families do you know that don't sometimes have major conflicts?" This woman was confronting the reality of the church and the unreality of her idealistic expectations. Soon she was going to have to make a choice about whether or not to stay involved in a genuine but messy and sometimes conflicted fellowship, or to leave and look for greener pastures where her idealistic dreams would be nurtured, at least until she really got involved with those people.

One of the things I love about the Bible is its realism about all sorts of things. Read the Bible and you get a clear picture of what life is really like. When people talk about experiencing church just like in New Testament times, I laugh to myself and wonder if they've ever read the New Testament. Make your way through this text and you'll find that almost every book bears witness to the reality of conflict in the church.

But the New Testament is also realistic about what it takes to overcome conflict. There are lots of specific instructions, some of which I've already surveyed in this series. But there are also the overarching principles that will help us find our way through the confusing maze of church conflict. The most important of these principles is love.

As you may know, there is one chapter in the Bible known as "The Love Chapter," and for good reason. 1 Corinthians 13 uses agape, one of several Greek words for "love," nine times. That's as much as in all four gospels combined. Only one other chapter in the whole Bible, 1 John 4, uses the word "love" more frequently. So if you want to know something about love, you'd do well to consult 1 Corinthians 13.

I often read this chapter in weddings these days. For a while it was out of style to use this text. But now 1 Corinthians 13 has come back into vogue. That's just fine with me, though I often wonder if couples getting married have really paid much attention to what the text says. Sure, it talks a lot about love. But the picture of love in 1 Corinthians 13 is decidedly non-romantic. In fact, you could almost say it's anti-romantic. It talks about love in realistic, down-to-earth terms. 1 Corinthians 13 says nothing about love being wonderful, happy, or heavenly. If you pay attention to what this chapter reveals, you'll realize that love is hard work, and much of it doesn't sound like much fun. Maybe that's why I like reading 1 Corinthians 13 in weddings. It cuts through the overly-romanticized, feeling-centered notions of love with the double-edged sword of God's realistic Word. It talks about what love is really all about, warts and all.

Of course Paul did not write 1 Corinthians 13 for weddings. It was written because the Corinthian church was in the middle of a big brouhaha over many things. The specific problem to which chapter 13 was addressed concerned the behavior of some Corinthian Christians in the common gatherings and the attitudes attached to that behavior. In a nutshell, some of the Corinthians got very excited about their spiritual abilities, especially the ability to speak in ecstatic, unknown languages – what we call speaking in tongues. Not only did these folks think they were spiritual giants because they could speak in tongues, but also they looked down upon those who didn't join them in their spiritual exhibitionism. Some of the tongues-speakers, it seems, may even have questioned whether the non-tongues-speakers were worth having around. This sunk in, and some of the non-tongues-speakers began to doubt their value to the community.

As Paul tried to clean up this mess in Corinth, he began by helping the Corinthians understand the ministry of the Spirit and the role of what he called "gifts" from the Spirit. These are given, Paul taught, not for the sake of the individual, but for the benefit of the community. A person who exercised some spiritual gift in the assembly, whether prophesying, healing, or speaking in tongues, did so only by the power of the Spirit and only for the common good. Spiritual gifts were not, therefore, a way of showing off one's spiritual prowess.

After laying out some basics on the Spirit, Paul proceeded to talk about the church as a human body. His main point with this image was to help the Corinthians understand that every single member had value to the church, just as every body part is necessary if the human body is to be healthy and whole. As Paul was wrapping up his discussion of the church as the body of Christ, he began to segue to some specific instructions on the use of spiritual gifts in the assembly. But then, almost as if he were interrupting himself, he wrote, "First, however, let me tell you about something else that is better than any of them [the spiritual gifts]" (1 Cor 12:31, NLT). With this preface he began to compose the passage we call 1 Corinthians 13. Here is the passage in a fairly recent and readable translation:

If I could speak in any language in heaven or on earth but didn’t love others, I would only be making meaningless noise like a loud gong or a clanging cymbal. If I had the gift of prophecy, and if I knew all the mysteries of the future and knew everything about everything, but didn’t love others, what good would I be? And if I had the gift of faith so that I could speak to a mountain and make it move, without love I would be no good to anybody. If I gave everything I have to the poor and even sacrificed my body, I could boast about it; but if I didn’t love others, I would be of no value whatsoever.

Love is patient and kind. Love is not jealous or boastful or proud or rude. Love does not demand its own way. Love is not irritable, and it keeps no record of when it has been wronged. It is never glad about injustice but rejoices whenever the truth wins out. Love never gives up, never loses faith, is always hopeful, and endures through every circumstance.

Love will last forever, but prophecy and speaking in unknown languages and special knowledge will all disappear. Now we know only a little, and even the gift of prophecy reveals little! But when the end comes, these special gifts will all disappear.

It’s like this: When I was a child, I spoke and thought and reasoned as a child does. But when I grew up, I put away childish things. Now we see things imperfectly as in a poor mirror, but then we will see everything with perfect clarity. All that I know now is partial and incomplete, but then I will know everything completely, just as God knows me now.

There are three things that will endure—faith, hope, and love—and the greatest of these is love. (1 Corinthians 13, NLT)

I'll get into the meat of this passage tomorrow. Today, in closing, I want to note its striking introduction.

The first verse is clearly aimed at the Corinthian tongues-speakers. If you speak in tongues, even a heavenly language (which may have been how the Corinthians talked about what they were doing), but don't have love, then you're just making a lot of meaningless racket. Of course this is ironic because the Corinthian tongues-speakers were quite aware that their "angelic speech" was unintelligible to others.

After taking a whack at the Corinthian trouble makers, Paul moves on to say, "If I had the gift of prophecy, and if I knew all the mysteries of the future and knew everything about everything, but didn't love others, what good would I be? [literally, "I am nothing"]" (v. 2). Some of the Corinthians were overly excited about knowledge, so Paul still has them in his aim. But when we get to chapter 14 we'll discover that Paul is going to be a strong advocate of prophecy. So in verse 2 he's not only targeting the Corinthians. He's got himself and his own values in view.

As the introduction to chapter 13 continues, Paul continues to target, not so much the Corinthians and their priorities as himself and his values. Even exemplary faith – such as Paul had – and costly self-sacrifice – such as Paul had displayed in his life – were worthless apart from love.

I deeply admire Paul's ability here, under the influence of the Spirit, to see his own virtues and values as meaningless without love. It would have been easy for him to accuse the Corinthians of missing the love boat while implying that he was somehow above the fray. But, in point of fact, Paul says: "Look, even the things I value the most, even the good gifts of God, even the attributes I exemplify, like faith and commitment, even these are nothing without love."

Paul's example challenges me to consider what I might value so highly as to act as if it matters more than love. I'm afraid the list is quite long, so I'll only mention a couple of my imbalances.

I'm really big on being right. I value tight arguments, especially when I make them. Also, because I care a whole lot about being right I hate being wrong. So, for me, the paraphrase of 1 Corinthians 13 might read: "If I am always right about everything, if my ideas are the best and my arguments always prevail, and yet I don't have love, then all of my rightness would be for naught."

In a related vein, I also care deeply about theological truth. I do my best to search the Scriptures for God's truth and to present it accurately. I can look a long way down my nose at people who make silly theological errors, or, worse yet, who don't seem to care as much as I do about theology. Now I don't think it's wrong to care about theological truth. On the contrary, it matters hugely. But, like Paul, I need to see even theological truth in light of love. So perhaps 1 Corinthians 13 in the "Mark Roberts Version" should read: "If I know the meaning of the Bible. If I study hard, working from the Greek and the Hebrew, and if I actually get the correct meaning, but don't have love, then I'm not worth one red cent."

Perhaps you might relate this text to yourself. What are the things you prize today more than love? How would you live differently this very day if everything you did and said was bathed in love? How would love add meaning and value to your life today?

Tomorrow I'll continue this discussion, looking especially at some of the essential characteristics of love.

What Love Is All About: 1 Corinthians 13:4-7

Part 11 of the series "God's Guidance for Christians in Conflict"

Post for Tuesday, May 3, 2005

Yesterday I began my investigation of love in 1 Corinthians 13. Today I continue by focusing especially on verses 4-7:

Love is patient and kind. Love is not jealous or boastful or proud or rude. Love does not demand its own way. Love is not irritable, and it keeps no record of when it has been wronged. It is never glad about injustice but rejoices whenever the truth wins out. Love never gives up, never loses faith, is always hopeful, and endures through every circumstance. (NLT)

Before I get into the details, a couple of preliminary comments are in order.

First, this passage has obviously been shaped to fit the crisis in Corinth. It has a corrective tone. I rather doubt that if Paul had been given the assignment to write a chapter on love without reference to a given church, he would have come up with eight "love is not" statements among the fifteen qualities of love. It's pretty clear that Paul is wanting to point out to the Corinthians where their own behavior is not loving. One might capture Paul's intent with this paraphrase:

Love is patient and kind, unlike you Corinthians in the way you treat each other. Love is not jealous, as you folks are. Love is not boastful, like you are. And so forth and so on.

Second, in a broader perspective, this description of love is, as I have mentioned before, extraordinarily realistic about human nature. Consider the subtext of these affirmations:

Love is patient.

Patience is necessary in human relationships because people will be slow, agonizingly slow. They'll get on your nerves. They'll keep making the same mistakes over and over. Therefore love has to be patient.

|

|

| |

Another take on love, from the 1970 film, Love Story. This movie popularized the classic line: "Love means never having to say you're sorry." I think I'll stick with 1 Corinthians 13. (If you're really feeling nostalgic, you can hear a clip of the theme from the movie, sung by Andy Williams, who else? [ .mov, 240K]) |

Love is not jealous.

Ah, but fallen human nature is so very jealous. We see somebody else get affirmation and we feel slighted. If someone else is blessed, we wish we were too. Sometimes we can even hate people who have what we want to have ourselves. Therefore love must not be jealous.

Love does not demand its own way.