My blog has moved! http://www.patheos.com/blogs/markdroberts/

|

|

Twitter Feed for My Recent Blog Posts and Other Tweets |

My blog has moved! http://www.patheos.com/blogs/markdroberts/

|

Hitchens Wrong About the Census, Eyewitnesses, St. Paul, Scholarship, Gospel Truth, and Gospel Disagreements

By Mark D. Roberts | Monday, June 11, 2007

Part 5 of series: god is Not Great by Christopher Hitchens: A Response

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

So far I’ve shown nine errors made by Christopher Hitchens in his treatment of the New Testament in god is not Great. Today I’ll add six additional errors.

Hitchens Wrong About the Augustan Census

He writes:

There is no mention of any Augustan census by any Roman historian . . . .” (112)

This comes in an argument where Hitchens is attempting to show that Luke’s account of the birth of Jesus is “quite evidently garbled.” But what Hitchens says is not true. In the Annals of the Roman historian Tacitus there is a reference to a document produced under Augustus that contained a description of “the number of citizens and allies under arms, of the fleets, of subject kingdoms, provinces, taxes” and so on,” in other words, a census. (Photo to the right: An obelisk in Rome that Augustus used to celebrate his greatness, including his being the son of a god.)

This comes in an argument where Hitchens is attempting to show that Luke’s account of the birth of Jesus is “quite evidently garbled.” But what Hitchens says is not true. In the Annals of the Roman historian Tacitus there is a reference to a document produced under Augustus that contained a description of “the number of citizens and allies under arms, of the fleets, of subject kingdoms, provinces, taxes” and so on,” in other words, a census. (Photo to the right: An obelisk in Rome that Augustus used to celebrate his greatness, including his being the son of a god.)

But we don’t even need to go to a Roman historian to find evidence for the censuses of Augustus. In “The Deeds of the Divine Augustus” written by Augustus himself and published throughout the empire in 14 AD, we read of three censuses conducted under Augustus’s authority (in 28 BC, 8 BC, and 14 AD; see Acts of Augustus, section 8). If Augustus decreed a census in 8 BC, as he claims, it’s quite possible that this was the census described in Luke 2, which was not finished in Judea until a year or two later.

Hitchens Wrong on the Eyewitnesses of the Crucifixion

In his denunciation of The Passion of the Christ, Hitchens notes that promoters said the film was based “on the reports of ‘eyewitnesses’.” (p. 111). Then he continues:

At the time, I thought it extraordinary that a multimillion-dollar hit could be openly based on such a patently fraudulent claim, but nobody seemed to turn a hair. (p. 111)

Nobody turned a hair because even the most skeptical of scholars believes that the accounts of Jesus’s death have some connection to eyewitnesses. The vast majority of New Testament scholars and classical historians believe that Jesus was in fact crucified under Pontius Pilate around 30 AD. This is found, not only throughout the New Testament, but also in the Roman historian Tacitus (Annals 15.44) and the first-century Jewish historian Josephus (Antiquities 18.3.3). It’s would be incredible to believe that the reports of Jesus’s death were not based at least to some extent on eyewitness accounts. This is made even more likely by the fact that the Gospels actually show the followers of Jesus in a very bad light during the passion of Jesus. Most of them abandoned Him, not exactly the sort of thing that early Christians would have made up unless it were true. (For a recent scholarly treatment of the role of eyewitnesses in the development of the Gospel material, see Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony by Richard Bauckham.) Even if one wishes to argue that eyewitnesses had little to do with the stories about Jesus’s death, an informed scholar would never say that the eyewitness claim is “patently fraudulent.”

Hitchens Wrong About Paul and Women

One of the first things Hitchens writes about the New Testament is:

The New Testament has Saint Paul expressing both fear and contempt for the female. (p. 54)

This is one reason among many Hitchens brings forth as part of his “consistent proof that religion is man-made” (p. 54).

Conveniently, Hitchens offers no references for his claim about Paul’s “fear and contempt” for the female. He offers no references because there are none. Indeed, there are four places in Paul’s letters where he says something about women that we might find uncomfortable, especially if we fail to consider the context in which Paul was writing and thus read him anachronistically (1 Corinthians 11, 14, 1 Timothy 2, Ephesians 5). But in none of these chapters is there anything vaguely resembling fear or contempt. Elsewhere in his writings, Paul strongly affirms the value of women, their role as his co-workers (Romans 16), their empowerment for ministry along with men (1 Corinthians 11-14), their extraordinary right to remain single, apart from male authority (1 Corinthians 7), and even their authority over their husbands’ bodies, along with the husbands’ authority over their bodies (1 Corinthians 7:4). In Paul’s light of Paul’s own culture, his view of women was shockingly progressive. This helps to explain why women, even powerful and wealthy women, we’re drawn to the early Christian movement (Acts 17:1-12; Romans 16:1-2).

Hitchens Wrong About New Testament Scholarship

He writes:

The contradictions and illiteracies of the New Testament have filled up many books by eminent scholars, and have never been explained by any Christian authority except in the feeblest terms of “metaphor” and “a Christ of faith.” (115)

Christopher Hitchens appears to have read a bit of what is sometimes called “liberal” New Testament scholarship. Here you find an effort to hang onto some measure of Christian faith while rejecting the historical core of the Gospel (the ministry, death, resurrection of Jesus). Marcus Borg provides a popular example of such an approach.

But Hitchens, once again, writes confidently about that which he does not know. For one thing, it rather begs the question to refer to the “contradictions and illiteracies of the New Testament.” But if we interpret Hitchens as referring, for example, to diverse treatments of Jesus among the four Gospels, then he is simply wrong to say that no “Christian authority” has explained these except in terms of “metaphor” and “a Christ of faith.” Some of the finest biblical scholars of recent times have done this with academic rigor and care, including F.F. Bruce, Martin Hengel, Ben Witherington III, Craig Evans, N.T. Wright, Richard Bauckham, and Craig Blomberg, just to name a few. Now it’s certainly possible to argue that these scholars are wrong. But it’s certainly wrong to reject their efforts as non-existent.

Hitchens Wrong on the Nature of the Gospels

He writes:

Either the Gospels are in some sense literal truth, or the whole thing is essentially a fraud and perhaps an immoral one at that. Well, it can be stated with certainty, and on their own evidence, that the Gospels are most certainly not literal truth. This means that many of the “sayings” and teachings of Jesus are hearsay upon hearsay upon hearsay, which helps explain their garbled and contradictory nature.” (120)

Virtually every scholar I’ve read, including the most skeptical, would agree that the Gospels are “in some sense literal truth.” The proof is that virtually every scholar who says anything about Jesus of Nazareth bases his or her history on the “facts” of the Gospels. So when a scholar states that Jesus was crucified under the authority of Pontius Pilate, this scholar takes at least that part of the Gospel account as literal truth.

It’s hard to know what Hitchens means by saying that the Gospels, “on their own evidence . . . are most certainly not literal truth.” But whatever he means, this cannot be sustained by a close reading of the Gospels. Now, let me add, that very few scholars, including conservative Christians, would argue that the Gospels are merely literal truth. They believe there is something more in the text. They are literal truth shaped in light of theological conviction. This isn’t a new idea. The Gospel writers say this very thing (see Luke 1:1-4, for example).

The “hearsay upon hearsay upon hearsay” claim shows ignorance of the oral culture in which the Gospel traditions were passed down. It’s an anachronistic mistake. I would point Hitchens to Bauckham’s book, Jesus and the Eyewitness, and to Kenneth Bailey, Poet and Peasant Through Peasant Eyes.

Finally, I’d be the first to admit that the sayings of Jesus are sometimes hard to understand. But one who refers to them as “garbled and contradictory” has simply not taken the time to understand them. One can certainly reject Jesus’s teaching as untrue, but to criticize them as “garbled and contradictory” says more about the critic than about the teaching itself.

Hitchens Invents or Exaggerates Gospel Disagreements

He writes:

The scribes cannot even agree on the mythical elements: they disagree wildly about the Sermon on the Mount, the anointing of Jesus, the treachery of Judas, and Peter’s haunting “denial.” (112)

One wonders in what sense the items Hitchens mentions should be included among the so-called “mythical elements.” Usually “mythical” is reserved for things like the miraculous birth, the miracles, etc. Be that as it may, Hitchens invents or exaggerates Gospel disagreements.

For example, the Gospel writers don’t disagree at all about the Sermon on the Mount because that “sermon” only appears in the Gospel of Matthew. Luke has a similar “sermon,” sometimes called “The Sermon on the Plain” but it’s not the same discourse. Furthermore, if you look closely at the different Gospel accounts of the anointing of Jesus, the treachery of Judas, and Peter’s denial, you will see some differences. The story of Peter’s denial, for example, is found in Matthew 26:69-75, Mark 14:66-72, and Luke 22:54-62. The three accounts are very similar, both in English and in the original Greek. The major difference has to do with whether the rooster crowed once or twice. But this could hardly be an example of the Gospel writers disagreeing wildly.

Is Hitchens a Reliable Witness?

I have now shown fifteen errors in Christopher Hitchens’s treatment of the New Testament. (A stickler would note that I’ve actually identified more than fifteen if I count every single mistake in a an excerpt.) These errors fall within relatively few pages of the overall book, only about 6% of the total. As I explained earlier, I’m not an expert in many of the areas about which Hitchens writes, so I’ll leave it to others to assess his accuracy there. But fifteen mistakes in relatively few pages doesn’t impress me positively.

But if Hitchens were a witness in a trial, a trial to determine whether God is great or not, and whether religion poisons everything or not, and if, after testifying for the prosecution, the defense was able to show that a small part of his testimony was filled with errors, then this would surely discredit him as a reliable witness. Some mistakes show up in the best of books, no doubt. But 15 mistakes in so few pages is unusually bad. Thus, ironically, I find myself with no option other than to treat Hitchens’s claims about “facts” with the sort of skepticism that he applies to the New Testament Gospels. He has not shown himself to be the kind of careful writer whom I can trust to be truthful.

Topics: Hitchens: god is not Great | 32 Comments »

Sunday Inspiration from Pray the Psalms

By Mark D. Roberts | Sunday, June 10, 2007

Excerpt

Why do the nations conspire,

and the peoples plot in vain?

The kings of the earth set themselves,

and the rulers take counsel together,

against the LORD and his anointed . . . .

Psalm 2:1-2

Click here to read all of Psalm 2

Prayer

Why, indeed, Lord? Why do nations and leaders rebel against You? Why do we so resist Your sovereignty? Why do we try to run our own lives, believing that we know better than You do? Why do we disobey Your will, or try to bend it to fit our personal preferences? Why do those of us who call You Lord fail to submit our lives to You? Why do we so often dishonor You in the way we live?

Why? Because sin claims our hearts. Because we reject our deepest created instinct, choosing instead to pretend as if we are gods. Because we seek wealth, power, security, and pleasure before we seek Your kingdom and righteousness.

Help our “kings,” the leaders of the nations, to submit to You, Lord. Help them to seek Your ways and to walk in them. Give them a passion for Your peace and justice.

And may the same be true for me in my small corner of this world. May I stop conspiring against You, and start offering myself fully to You in all things. May I live in a way that honors You in all I say and do.

Postscript

In the original setting of Psalm 2, the “anointed” of God is the human king of Israel. Christian readers see in this psalm something more . . . a sign pointing ahead to the coming of the Anointed One known to us as Christ (from the Greek word christos, which means “anointed one”).

Kings Canyon National Park in California at sunset

Kings Canyon National Park in California at sunset

Topics: Sunday Inspiration | 1 Comment »

Hitchens Wrong about Q, Hell (Twice), Nag Hammadi, Canon, and Tampering

By Mark D. Roberts | Saturday, June 9, 2007

Part 4 of series: god is Not Great by Christopher Hitchens: A Response

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

In yesterday’s post I pointed out three errors in Christopher Hitchens’s recent book, god is not Great. In today’s post I’ll deal briefly with six more errors. I’ll finish up with the next six on Monday.

Hitchens Mistaken About the Nature of Q

Hitchens writes:

The book on which all four [New Testament Gospels] may possibly have been based, known speculatively to scholars as “Q,” has been lost forever, which seems distinctly careless on the part of the god who is claimed to have “inspired” it. (112)

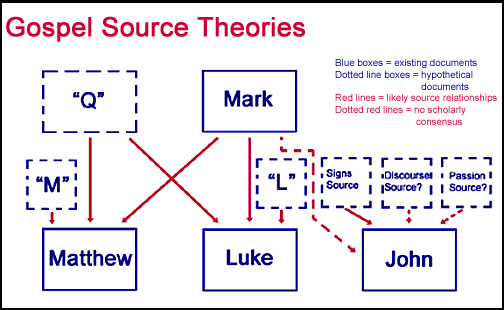

Q is a hypothetical document invented by New Testament scholars to explain the complex relationships between the three synoptic gospels, Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Most New Testament scholars affirm the existence of Q or something like it, though quite a few find this hypothetical document to be unnecessary. (Hitchens would like the Ockham’s razor approach of these non-Q-ites!) I happen to believe that something like Q existed. If you’re looking for a more detailed explanation of what I have said so briefly, you can check out chapter five of my book, Can We Trust the Gospels? I’ll include here a chart that shows up in that chapter so you can see how the Gospels might be related to each other and to Q.

So what does Hitchens get wrong? Q is not the book on which all four [Gospels] may possibly have been based. No New Testament scholar believes this. By definition, Q contains that which almost never shows up in the Gospel of Mark, so nobody argues that Mark was based on Q. And, to my knowledge, nobody believes that John was based on Q either, though John may or may not have had access to another Sayings Source. Clearly, Hitchens does not understand the nature of Q.

I should also add, though I don’t count this among the fifteen errors, that nobody to my knowledge has ever argued that God inspired Q. The scholars who are enamored with Q tend not to think much in terms of God’s inspiration of the Bible anyway. And those of us who value inspiration don’t try to smuggle Q into the canon, though we regard it as a helpful source of Jesus’s sayings.

Hitchens Wrong in Saying that Only Jesus Mentioned Hell

Hitchens writes,

“This distinction [between the Old Testament and the New with respect to an ill-tempered god] is more apparent than real, since it is only in the reported observations of Jesus that we find any mention of hell and eternal punishment” (175).

Christopher Hitchens doesn’t like the idea of Hell. In this he is joined by many Christians, actually, including me. But we affirm the idea of Hell (in various forms and non-forms) because we find it taught in Scripture in many places. Jesus does mention Hell and eternal punishment, and in this Hitchens is correct (for example, Matthew 5:29-30). But the notion of Hell and/or post-mortem punishment shows up elsewhere in the New Testament (for example, 2 Thessalonians 1:6-10; 2 Peter 2:4-10; Jude 7; Revelation 20:11-15).

Now I can just hear Hitchens laughing, believing that I have won the point but lost the argument. After all, he is an enthusiastic critic of the notion of Hell, and believes the whole idea of Hell gives good reason to reject both religion and God. My response to this would be three-fold:

1. I am not dealing now with the rightness or wrongness of Hell, but only with the rightness or wrongness of Hitchens’s purported statements of fact.

2. The biblical imagery of Hell, like biblical imagery associated with the apocalypse, should be read in context. Whatever Hell actually is, it may not be a literal lake of fire. The point of such imagery is, among other things, to help us to realize that what we do and think and believe in this life really matters, both for now and forever.

3. I expect that at some time in the future I’ll need to do some blogging on Hell. For now, if you’re wondering about what Hell is really all about, I’d encourage you to read The Great Divorce by C. S. Lewis. This is also a wonderful book on heaven . . . a work of fiction that is full of truth.

Hitchens Wrong That Jesus Invented the Idea of Hell

Hitchens writes:

Not until the advent of the Prince of Peace do we hear of the ghastly idea of further punishing and torturing of the dead. (175-176)

Hitchens is right in part. The idea of Hell is not plainly taught in the Old Testament, but only hinted at (see, for example, Psalm 9:17). He also notes on page 176 that John the Baptist presages the notion of eternal judgment, fairly connecting John with the “advent of the Prince of Peace.”

But the idea of post-mortem punishment of evil-doers was not original to Jesus. We find this idea in Jewish writings that come from the time prior to and contemporaneous with Jesus. Many of these are apocalyptic in nature, and are not well known today. They would include: Apocalypse of Abraham 15:6-7; Apocalypse of Zephaniah 10:3-14; Sirach 12:9-10; 4 Ezra 7:75-101; Sibylline Oracles 1:100-103; 2:290-310. The precise dating of these books is difficult, but they show that Jesus was not unique among Jews of His day when He envisioned punishment beyond this life.

Hitchens Mistakes the Dating of the Nag Hammadi “Gospels”

He writes:

These scrolls were of the same period and provenance as many of the subsequent canonical and “authorized” Gospels, and have long gone under the collective name of “Gnostic.” (p. 112)

There is one nit-picky error here that I haven’t counted as a mistake. The Nag Hammadi documents are codices (ancient books) not scrolls. Sir Leigh Teabing made a similar error once, but I won’t go there now.

More to the point, the Gnostic writings were not “of the same period and provenance” as the canonical Gospels. Though there’s an open debate on the dating of the Gospel of Thomas, the likely dependence of Thomas on the New Testament Gospels places its composition later than the biblical varieties. (See the references below.) The rest of the Gnostic gospels were almost certainly written well after the biblical Gospels. Hitchens’s use of “subsequent” is particularly off base.

References for the dating of the Gospel of Thomas: K.R. Snodgrass, “The Gospel of Thomas: A Secondary Gospel,” Second Century 7 (1989-1990): 19-38; C. M. Tuckett, “Thomas and the Synoptics,” Novum Testamentum 30 (1988): 132-57; C. A. Evans, “Thomas, Gospel of” in Dictionary of the Later New Testament and Its Developments, ed. Ralph P. Martin and P. H. Davids (Downers Grove: Inter-Varsity Pres, 1997) 1175-1177.

Hitchens Wrongly Describes the Debate Over the Inspiration of the Gospels

He writes:

For a long time, there was incandescent debate over which of the “Gospels” should be regarded as divinely inspired. Some argued for these and some for others, and many a life was horribly lost on the proposition.” (113)

Once more, it feels as if I’m back debating Sir Leigh Teabing. Though there were a couple dozen so-called “Gospels” that did not end up in the Christian Bible, there is little evidence of much debate about which Gospels to include and which not to include. What’s pretty clear is that the orthodox had their four Gospels, and the Gnostics had their many “Gospels,” and they didn’t agree which were authoritative. But there wasn’t much debate between Gnostics and the orthodox. And what there might have been could hardly be called incandescent. As to the lives “horribly lost” part, this is so fantastic as to be laughable, except I don’t think it was meant as a joke by Hitchens.

If you’re looking for a succinct discussion of how the New Testament Gospels made it into the canon of Scripture, I’d recommend Chapter 15 of my book, Can We Trust the Gospels? This chapter is entitled: “Why Do We Have Only Four Gospels in the Bible?” For a more detailed discussion, check out F.F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture.

Hitchens Repeats Mencken’s Mistake Concerning Tampering With the New Testament Documents

He quotes H.L. Mencken approvingly (”Mencken irrefutably says”):

. . . and that most of them [the New Testament documents], the good along with the bad, show unmistakable signs of having been tampered with. (110).

One can only wonder what Mencken meant, and what Hitchens thinks he meant. The most charitable reading I can make of this claim is that the scribes didn’t get every word of the New Testament manuscripts correct. But tampering suggests something much more sinister and intentional than this, at least in most cases. The fact is that the New Testament documents, including the Gospels, are better attested than any documents of the ancient world, a fact I defend in Can We Trust the Gospels? You can read the relevant chapter online, if you wish (PDF file).

The passage from Mencken, quoted by Hitchens, appears in the book Treatise on the Gods, which was published in 1930. Like Hitchens, Mencken was a rhetorically-clever opponent of Christianity. But, contrary to Hitchens’s claim, Mencken did not write “irrefutably” on the New Testament. Cleverly? Yes. Accurately? No. Irrefutably? You’ve got to be kidding.

Topics: Hitchens: god is not Great | 38 Comments »

Hitchens Mistaken About a Date, a Name, and the Gospels

By Mark D. Roberts | Friday, June 8, 2007

Part 3 of series: god is Not Great by Christopher Hitchens: A Response

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

Warning: Long post to follow!

In yesterday’s post I said that I have found many errors in god is not Great by Christopher Hitchens. These errors have been in the area of my academic expertise: New Testament and New Testament scholarship. I’ll leave it to other experts to evaluate the accuracy of other portions of god is not Great. But I must confess that I was not impressed by Hitchens’s grasp of the material I know well, and that has led me to question his overall reliability as a source of “facts.”

I have found fifteen errors in Hitchens’s treatment of the New Testament, as well as sixteen misunderstandings or distortions. Some of the clear errors are not major in terms of content, but they reveal a kind of sloppiness that is unsettling.

Hitchens Mistaken on the Date of Jesus’s Birth

For example, Hitchens writes:

“This [year 2000 hysteria] was no better than primitive numerology: in fact it was slightly worse in that 2000 was only a number of Christian calendars and even the stoutest defenders of the Bible story now admit that if Jesus were ever born it wasn’t until at least AD 4.” (pp 59-60)

Nobody, to my knowledge, dates the birth of Jesus to AD 4. Every scholar puts his birth earlier than 4 BC (the date of King Herod’s death). The most likely date for Jesus’s birth seems to be around 6 BC. My guess is Hitchens remembered the “4″ correctly but not the era. A minor mistake, but an unsettling one.

Hitchens Gets Bart Ehrman’s Name Wrong

To cite one further example of this sort, Hitchens twice refers to the scholar Bart D. Ehrman as “Barton Ehrman” (p. 120, 142). To my knowledge, “Bart” is Mr. Ehrman’s full first name. So, unless he has a nickname unknown to me, it’s an error to call the man “Barton.” Again, this is not a substantial error, but it does suggest a distressing lack of accuracy. (It also leaves me completely unimpressed with the editing of this book. Authors make mistakes. I’ve certainly made plenty in my time. Good publishers have good editors and fact-checkers who catch mistakes.)

By the way, let me clarify something I said in the debate about Ehrman. He is a highly-regarded New Testament scholar, who has done some fine work. I once used one of his books in a seminary course I was teaching. I disagree with him at many points, but I respect his work. I do believe that Ehrman’s opposition to Christianity does color some of his arguments and conclusions, but no more that my own work reflects my Christianity. If you’re interested, in a new book that refutes Ehrman’s Misquoting Jesus, check out Misquoting Truth: A Guide to the Fallacies of Bart Ehrman’s “Misquoting Jesus” by Timothy Paul Jones. HT: Melinda at Stand to Reason)

By the way, let me clarify something I said in the debate about Ehrman. He is a highly-regarded New Testament scholar, who has done some fine work. I once used one of his books in a seminary course I was teaching. I disagree with him at many points, but I respect his work. I do believe that Ehrman’s opposition to Christianity does color some of his arguments and conclusions, but no more that my own work reflects my Christianity. If you’re interested, in a new book that refutes Ehrman’s Misquoting Jesus, check out Misquoting Truth: A Guide to the Fallacies of Bart Ehrman’s “Misquoting Jesus” by Timothy Paul Jones. HT: Melinda at Stand to Reason)

At this point my criticis will no doubt say that I’m nit-picking, that the errors in god is not Great are insubstantial. My response, as one who has graded hundreds of graduate school papers over the years, is that you can almost always see the quality of a writer’s thinking in how he or she deals with seemingly insignificant details. ‘A’ papers generally get the names and dates right in addition to the main arguments. Sloppiness in small things is generally an indicator of sloppiness in larger things.

Hitchen’s Gets the Nature of the Gospels Wrong

So now to a larger “fact” that Hitchens gets wrong. He writes:

“However, he [Maimonides, the Jewish rabbi and philosopher] fell into the same error as do the Christians, in assuming that the four Gospels were in any sense a historical record. Their multiple authors–none of whom published anything until many decades after the Crucifixion–cannot agree on anything of importance.” (111)

There are two main problems with this statement. The first problem is calling it an “error” to “assum[e] that the four Gospels were in any sense a historical record.” Even the most skeptical of scholars see the Gospels as a historical record in some sense. Most famously, even the Jesus Seminar, which turned skepticism about the Gospels into a media sensation, gave a historical thumbs up (red beads, actually) to some of the sayings and actions of Jesus in the New Testament Gospels. I don’t know of any credible scholar who claims that there is no historically reliable material in the Gospels. Ancient historians and classicists generally regard the Gospels as substantially historical, and regard the hyper-skepticism of many New Testament scholars as aberrant.

As much as I think Hitchens made a mistake in what he wrote about the Gospels as not being a historical record in some sense, I actually didn’t count this among the fifteen clear errors, because I was giving him a generous benefit of the doubt. However, the next problem in the same excerpt is an indisputable error.

Hitchens writes that the “multiple authors” of the Gospels “cannot agree on anything of importance.” This is plainly wrong, unless, I suppose, we allow Hitchens to fill in the blanks of what counts as important. He might say that nothing of importance at all is addressed in the Gospels. (Later he will say that “Thanks to the telescope and the microscope, [religion] no longer offers an explanation of anything important.” [282]). Be that as it may, his point on page 111 is that the Gospels are full of disagreement, especially about the things that matter about Jesus, as the context makes clear.

This is simply not true. Though it is true that the New Testament Gospels show considerable diversity in their portraits of Jesus, they agree on many, many things, including matters that are most important both to the Gospel writers and to Christian believers.

In my book, Can We Trust the Gospels?, I devote two chapters to this issue. Chapter 8 is called “What Difference Does It Make That There Are Four Gospels?” Chapter 9 is called “Are There Contradictions in the Gospels?” I do not at all try to minimize the genuine differences among the Gospels. Any careful reader can’t help but see them, whether in the stories of Jesus’s birth or in the stylistic differences between Mark and John. In fact, the early Christians celebrated the unique qualities of the different Gospels. But I also show in considerable detail the extent to which all four Gospels agree on much of what pertains to Jesus, including the most important aspects of His ministry and message.

At the end of Chapter 8, I include a list of 33 key facts about Jesus that are found in all four gospels. I’ll mention about half of these points of agreement here:

• Jesus ministered during the time when Pontius Pilate was prefect of Judea (around A.D. 27 to A.D. 37).

• Jesus had a close connection with John the Baptist, and his ministry superseded that of John.

• Jesus’s ministry took place in Galilee.

• Jesus’s ministry concluded in Jerusalem.

• Jesus gathered disciples around him. (This is important, because Jewish teachers in the time of Jesus didn’t recruit their own students, rather the students came to them.)

• Jesus taught women, and they were included among the larger group of his followers. (This, by the way, sets Jesus apart from other Jewish teachers of his day.)

• The ministry of Jesus involved conflict with supernatural evil powers, including Satan and demons.

• Jesus used the cryptic title “Son of Man” in reference to Himself and in order to explain His mission. (Jesus’s fondness for and use of this title was very unusual in his day, and was not picked up by the early church. This is a hugely important point for the one who seeks to understand Jesus.)

• Jesus saw his mission as the Son of Man as leading to his death. (This was unprecedented in Judaism. Even among Jesus’s disciples it was both unexpected and unwelcome.)

• Jesus, though apparently understanding himself to be Israel’s promised Messiah, was curiously circumspect about this identification. (This is striking, given the early and widespread confession of Christians that Jesus was the Messiah.)

• Jesus did various sorts of miracles, including healings and nature miracles.

• Jesus was misunderstood by almost everybody, including his own disciples.

• Jesus experienced conflict with many Jewish leaders, especially the Pharisees and ultimately the temple-centered leadership in Jerusalem.

• Jesus spoke and acted in ways that implied He had a unique connection with God.

• Jesus was crucified in Jerusalem, at the time of Passover, under the authority of Pontius Pilate, and with the cooperation of some Jewish leaders in Jerusalem. (There are quite a few more details concerning the death of Jesus that are shared by all four gospels.)

• Most of Jesus’s followers either abandoned Him or denied Him during His crucifixion.

• Jesus was raised from the dead on the first day of the week.

• Women were the first witnesses to the evidence of Jesus’s resurrection. (This is especially significant, since the testimony of women was not highly regarded in first-century Jewish culture. Nobody would have made up stories with women as witnesses if they wanted them to gain ready acceptance.)

My list of Gospel agreements doesn’t even begin to tally up the less explicit but ultimately crucial agreements in matters of worldview. The Gospel writers share a common view of reality, one that includes a personal, creator God who has been active in human affairs, especially those of Israel, and so forth and so on. Someone from a culture not influenced by Judeo-Christianity would undoubtedly see commonalities that I take for granted.

As I read god is not Great, and as I’ve read other things Christopher Hitchens has written, it’s obvious to me that he has a good bit of familiarity with the New Testament Gospels. I’d even be willing to bet that he knows the Gospels better than many Christians. Thus I am at a loss to explain why he would say that they “cannot agree on anything of importance.” Even allowing for a good bit of polemical freedom, such a statement is so plainly wrong that it cannot but undermine the reader’s confidence in Hitchens’s reliability.

If would be perfectly fair for Hitchens to have said, “The Gospels agree on many things about Jesus, most of which are rubbish.” Of course I’d beg to differ with the rubbish bit, but at least it would be a fair point for him to have made. But it just isn’t correct for Hitchens to say that the four Gospels “cannot agree on anything of importance.”

Thus I come to the end of my long discussion of the first three of Hitchens’s errors concerning the New Testament and New Testament scholarship. The first two are admittedly small, but suggestive. The third error is important enough to have merited lengthy analysis. In subsequent posts I’ll move more quickly through the other errors so as to get through this material in a reasonable number of posts.

Topics: Hitchens: god is not Great | 48 Comments »

Is Hitchens a Reliable Source of “Facts”?

By Mark D. Roberts | Thursday, June 7, 2007

Part 2 of series: god is Not Great by Christopher Hitchens: A Response

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

Few books will divide the house more than god is not Great. Atheists will happily devour it; religious folks will find it most distasteful. My guess is that few books are more polarizing than this particular volume.

Yet I think I can say something about god is not Great that everyone can agree with: It is filled with purported statements of fact. Those who like Hitchens may be unhappy with “purported,” but surely they must understand that by using this word I’m not necessarily denying the truthfulness of Hitchens’s claims. I’m simply noting that god is not Great is filled with thousands of statements that appear to be factual.

The is worth mentioning because many books on religion and philosophy contain endless arguments and ideas, but not many so-called facts. Books like these are valuable, of course, but they are often hard to assess. Arguments and ideas cannot be easily tested as to their truthfulness. Claims of fact often can be check out rather quicly (but not always, of course. It’s a little hard to verify the fact of the Big Bang or the existence of quarks.).

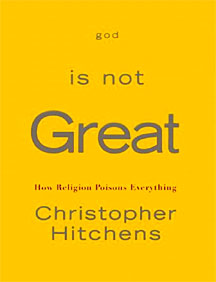

For example, if I were to say that god is not Great offers several arguments that are valid and many that are invalid, which I do in fact believe, this thesis would take quite a bit of effort to demonstrate. That’s the main point of this extended blog series on god is not Great. But if I were to say that the cover of god is not Great is blue, this could be easily checked out. You could quickly disprove my purported statement of fact by comparing it with the data. And this comparison would not bode well for me, since the cover of god is not Great is quite clearly yellow. One might call it mustard or ocher or “bananaish” or some other variety of yellow, but blue simply won’t work.

For example, if I were to say that god is not Great offers several arguments that are valid and many that are invalid, which I do in fact believe, this thesis would take quite a bit of effort to demonstrate. That’s the main point of this extended blog series on god is not Great. But if I were to say that the cover of god is not Great is blue, this could be easily checked out. You could quickly disprove my purported statement of fact by comparing it with the data. And this comparison would not bode well for me, since the cover of god is not Great is quite clearly yellow. One might call it mustard or ocher or “bananaish” or some other variety of yellow, but blue simply won’t work.

The obvious fact that god is not Great contains many apparent facts, therefore, gives us an advantage in trying to evaluate its overall truthfulness. If Hitchens tends to get his facts right, then we would do well to pay close attention to his claims, even those that are not factual per se. He will have shown himself to be a reliable witness and a careful thinker. If, on the contrary, he gets many of his facts wrong, then we would rightly be inclined to doubt what he writes about many things and chalk it up to sloppy thinking.

This fact-checking approach seems to provide a fair and rational way forward in our effort to evaluate god is not Great. In fact, it keeps us within the realm of the rational and scientific, a realm that Hitchens almost seems to regard as the kingdom of God. Yet the plethora of purported facts in this book also makes such evaluation difficult. Why? Because this book contains so many different alleged facts concerning so many different subjects. Yes, religion is in the center of Hitchens’s target, but he tends to shoot with buckshot rather than a silver bullet. god is not Great contains page after page of ostensible facts having to do with history, culture, literature, philosophy, theology, and current events, in addition to religion. Thus it would be difficult for the average person to evaluate Hitchens’s claims without doing a whole lot of research for a whole long time.

Christopher Hitchens knows more about many things than I do. Right or wrong, his grasp of history exceeds mine, as does his knowledge of current events and even certain religions, mainly Islam. But there are a few topics in which I have greater expertise than Hitchens. Given his apparently naïve and curiously modernist view of human knowing, (”Our belief is not a belief. Our principles are not a faith.” p. 5), I may know epistemology (the philosophy of knowledge) better than he. Likewise with philosophical ethics. I am quite sure that I have much more knowledge of what it’s like actually to be a Christian than Christopher (whose name in Greek means “Christ-bearer” by the way). I’m sure he’d quite happily grant me this advantage over him. And I’m positive that I know the New Testament and the field of New Testament studies better than Hitchens. This isn’t a matter of boasting. One would hope that somebody with a Ph.D. in New Testament actually had a bit of expertise in the field. While Christopher Hitchens was traveling the world as a journalist, I was burrowed into the library at Harvard, studying ancient languages and documents, and reading more New Testament scholarship than anyone other than a scholar would find valuable.

Therefore, as I read god is not Great, wading through Hitchens’s rhetorically-charged version of many purported facts, I was especially attentive to his statements about the New Testament and related scholarship. Would he get these “facts” right? Would he say things that most honest scholars, no matter their theological persuasion, would affirm? If Hitchens scored relatively high in his truth score when it came to the New Testament, then I’d be inclined to believe him about other things as well. He would have shown himself to be a careful thinker, researcher, and writer. If, however, Hitchens scored low in his New Testament truth score, if he made obvious errors and biased misstatements, then I would tend to question his reliability about other statements of fact as well.

The bad news for Christopher Hitchens is that he gets a low mark for accuracy when it comes to his statements about the New Testament and New Testament scholarship. In fact, I found fifteen factual errors in this material. I also identified sixteen statements that show what I consider to be a substantial misunderstanding or distortion of the evidence, even though a few scholars might agree with Hitchens. That’s why I distinguish between factual errors and misunderstandings/distortions, in an effort to be clear and fair.

If my evaluation is anywhere near correct, this does not reflect well upon god is not Great, since the New Testament material comprises only about 6% of the whole book. How many other errors fill the pages of this book? I’ll let suitable experts answer this question. But the obvious implication of what I discovered is that Christopher Hitchens is not a reliable reporter of facts, probably because has not done his homework adequately. He is, after all, a brilliant man with an inquisitive and well-tuned mind. Given my evaluation of his errors in the field I know best, however, I’m inclined to question his statements of “fact” concerning many other things. And my disbelief is not a belief. It’s a reasonable conclusion based on the facts of Hitchens’s numerous mistakes and misstatements.

Of course for this conclusion to be valid, I need to show specifically where Hitchens makes errors in his treatment of the New Testament and New Testament scholarship. I won’t be able to do this responsibly in this post, since I’ve already put up more words today than most readers prefer in a single blog entry. I’ll begin to examine Hitchens’s mistakes tomorrow.

In the meanwhile, if you own a copy of god is not Great, why don’t you see if you can spot any errors. Most of them can be found in pages 110 through 120.

Topics: Hitchens: god is not Great | 71 Comments »

Introduction

By Mark D. Roberts | Wednesday, June 6, 2007

Part 1 of series: god is Not Great by Christopher Hitchens: A Response

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

A few hours ago I had the opportunity to debate Christopher Hitchens on the subject of his recent bestseller: god is not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. For three hours (including commercials) Mr. Hitchens and I stood toe-to-toe (electronically speaking) on the Hugh Hewitt Show, a talk-radio program. (Note: if you missed this program live, it will soon be available on the Internet. Check this website. Picture to the right: Christopher Hitchens holding forth.)

The specific topics for the debate were selected by Hugh, who moderated the program. Though he and I are friends, he did not tell me what the topics would be in advance. He and I both knew it was important for us to play fair in this debate (which meant, of course, that I way over-prepared, since I needed to be able to cover every possible topic raised by Hitchens’s book). Some of this over-preparation will now pay off as I begin to blog about god is not Great.

The specific topics for the debate were selected by Hugh, who moderated the program. Though he and I are friends, he did not tell me what the topics would be in advance. He and I both knew it was important for us to play fair in this debate (which meant, of course, that I way over-prepared, since I needed to be able to cover every possible topic raised by Hitchens’s book). Some of this over-preparation will now pay off as I begin to blog about god is not Great.

To be honest, I felt pretty nervous before the debate. Though I have some expertise in Christianity, and especially in the field of New Testament, and though I have been a pastor and adjunct seminary professor for many years, I am not one who regularly engages in apologetic defenses of Christian faith. Others are much better than I at such efforts (such as Dr. Craig Hazen and his Biola colleagues, including Greg Koukl and Dr. John Mark Reynolds. Prior to my conversation with Hitchens, I spoke with these three brilliant defenders of Christian faith, and am grateful for their counsel. It’s good to have smart, godly friends!)

My pre-debate nervousness was increased by the fact that Christopher Hitchens is a bright, well-educated, quick-thinking, widely-read, rhetorically-brilliant and dagger-tongued debater. Plus, for the last month he’s been going around the country sparing with religious and academic types about his book. By now his attacks and defenses will have been finely tuned for maximum effectiveness. Plus, there’s the fact that Mr. Hitchens speaks with a British accent, which means he’d sound better than I no matter the content of our presentations.

There is also the issue of the format. Talk radio, in most cases, is not well suited to careful, reasoned, extensive discourse. It’s much better for soundbites, which Hitchens cranks out in droves. But this makes it challenging to engage in logical discourse, especially when the issues are complex. One could easily win the argument, logically, but lose the war in terms of the impact on listeners.

I had hoped that both Christopher Hitchens and I would have done the debate from Hugh’s radio studio. I looked forward to the chance to talk with Mr. Hitchens face-to-face. Human communication is usually better this way, even in a debate format. Unfortunately, however, he preferred to call in his part over the telephone, which is common in the radio business. I can imagine that Christopher Hitchens is, by now, pretty tired of debating us religious folk. I don’t blame him for wanting to phone it in.

How did the debate go? Overall, I think it was fair and reasonably informative. As I think over my responses, I’d love to go back and change a few. By far the hardest thing about debating Christopher Hitchens is his tendency to throw out a lot of critical claims all at once. I found myself needing to choose which to pick up and which to leave on the table. This was frustrating, since I feared that one might assume I agreed with things I just didn’t have time to refute. My blog will give me the chance to be both clearer and more complete.

I mentioned a number of resources in the debate, and will put up links to these in case you want to track them down. Then I’ll say a bit more about the last resource on the list:

Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony

Owen Gingerich, God’s Universe

Francis S. Collins, The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief

Elaine Howard Ecklund. “Religion and Spirituality among University Scientists”

I did not bring up the Ehrman book. Hugh did, I believe, because it figures prominently in god is not Great. Though there are many fine insights in Misquoting Jesus, I don’t generally recommend it because it has much that is distorted and unhelpful. In fact, I wrote a substantial critique of this book shortly after it was published.

In our conversation about Ehrman, Hitchens mentioned something he said in his book, that he chose Ehrman “on the basis of ‘evidence against interest’: in other words from someone whose original scholarly and intellectual journey was not at all intended to challenge holy writ” (p. 122). Apparently, Hitchens believed that Ehrman was still some sort of Christian or theist, albeit not of the fundamentalist stripe. Hitchens seemed taken aback when I noted that Ehrman is not a believer, but gave up his faith a long time ago. Hitchens said he would check this out.

In my off-the-cuff comments on Ehrman, I was essentially correct, though I got a couple of details wrong. I think I said that he lost his faith in grad school, and has been an atheist for three decades, and has during that time published literature opposing orthodox Christianity. After the debate I checked my facts, and found that Ehrman considers himself an agnostic, not an atheist. Moreover, given that he finished his PhD in 1985, it would be more accurate to say he’s been a non-theist for over twenty years, not thirty. Nevertheless, the fact that he hasn’t been a Christian for his entire professional and publishing life doesn’t make Ehrman a good example of “evidence against interest.” It’s obvious, especially in Misquoting Jesus, that Ehrman has plenty of interest in debunking Christian belief. He isn’t hiding this fact, even as I don’t hide the fact that I am a Christian and that this influences my thinking and writing.

My source of information about Ehrman’s rejection of Christianity is a little essay he wrote called “An Agnostic Reflects on Christmas.” There he explains how, even though he no longer believes in the message of Christmas, he is still touched by Christmas stories and celebrations, especially Christmas trees. Ironically, Bart Ehrman and I agree profoundly on this last point. I am also a big lover of Christmas trees, as I have made abundantly clear in past blogging. I’m happy to say that Ehrman and I part company on the truth of Christmas, however.

In my next post in this series I’ll begin to examine aspects of Hitchens’s case against God and religion, and why I believe this case is less than convincing.

Topics: Hitchens: god is not Great | 31 Comments »

The Great God Debate

By Mark D. Roberts | Tuesday, June 5, 2007

Today I’m participating in what Hugh Hewitt has called “The Great God Debate.” For three hours on Hugh’s syndicated radio program I’ll be debating with Christopher Hitchens, author of the recent book: god is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. I don’t know how great the debate will be, but I hope I can honor the greatness of God both through what I say and in how I say it.

Beginning tomorrow, I’ll be blogging on Hitchens’s book and on the issues from our debate. (Yes, I’m going to interrupt my series on the mission of God in order to do this.) One of the first things I’ll do is to put up links to the resources I mention in the debate (books, articles, etc.). Since I haven’t done the debate yet, I can’t put up the links now.

The one resource I expect to mention is my newest book, Can We Trust the Gospels? Investigating the Reliability of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. This book is not out yet, but Amazon promises to be mailing in on Thursday. So we’ll see. You can order a copy of this book from Amazon by clicking here. Ironically, or perhaps providentially, depending on where you’re coming from philosophically, Amazon has paired my book with Hitchens’ god is Not Great, as you’ll see on my Amazon page.

The one resource I expect to mention is my newest book, Can We Trust the Gospels? Investigating the Reliability of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. This book is not out yet, but Amazon promises to be mailing in on Thursday. So we’ll see. You can order a copy of this book from Amazon by clicking here. Ironically, or perhaps providentially, depending on where you’re coming from philosophically, Amazon has paired my book with Hitchens’ god is Not Great, as you’ll see on my Amazon page.

You can get an advance look at the first two chapters of the book from the Crossway Books website. Click here to view the PDF of the first two chapters.

Now, if you’ll pardon a good bit of shameless promotion, I’ll print some of the endorsements I’ve received for Can We Trust the Gospels? Many thanks to those who read this book and offered their kind words.

“Mark Roberts has produced what has long been needed: a highly read- able and compelling account of why Christians can indeed trust the Gospels. Dr. Roberts is a formidable scholar whose reputation is very high among academics. He is a skilled writer and teacher. He is also an innovative force in the world of Christian apologetics, among the very first to see the potential for blogging as a formidable means of pursuing the Great Commission.

“I have had Dr. Roberts on my radio show more than any other theolo- gian or pastor, for several reasons. First, he has been a very good friend for a long time. But much more important is his ability to communicate and the knowledge he has accumulated through his three decades of serious and thorough study of the Gospels and the scholarship around them. Whenever a major controversy erupts that touches on the Christian faith, I call on Dr. Roberts.

“Can We Trust the Gospels? is quite simply the best effort I have ever read by a serious scholar to communicate what scholars know about the Gospels and why that should indeed encourage us to trust them and thus to trust Jesus Christ.”

—Hugh Hewitt, radio talk show host, author, blogger, and Professor of Law at Chapman University School of Law

“There is a crisis of confidence about the Gospels, fueled by sensational claims about supposedly new Gnostic Gospels with a ‘revised standard’ view of Jesus. With a pastor’s insight but a scholar’s critical acumen, Mark Roberts provides a readable guide to answering the question, Can we trust the Gospels? As Mark makes clear, the earliest and best evidence we have for the real Jesus is the canonical Gospels, not the much later Gnostic ones.”

—Ben Witherington III, Professor of New Testament, Asbury Theological Seminary, author of What Have They Done with Jesus?

“What F. F. Bruce did for my generation of students, Mark Roberts has done for the current generation. Any student who asks me if our Gospels are reliable will be given this book, and then I’ll buy another copy for the next student!”

—Scot McKnight, Karl A. Olsson Professor in Religious Studies, North Park University

“Can We Trust The Gospels? caught me completely by surprise. While I knew a scholar of Mark Roberts’s caliber could convince skeptics the Gospels are reliable, I never expected to have my own preconceptions uprooted and replaced with a more solid trust in these biblical texts. This book not only makes a compelling case for trusting the Gospels, it illuminates the creative ways in which God worked to bring us His Word. Roberts’s brilliant little book deserves to be widely read by both skeptics and believers.”

—Joe Carter, blogger (evangelicaloutpost.com) and Director of Communications for the Family Research Council

Topics: Gospels | 9 Comments »

Sent to Proclaim the Good News, Part 3

By Mark D. Roberts | Tuesday, June 5, 2007

Part 9 of series: The Mission of God and the Missional Church

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

In my last two posts I’ve been explaining how we who believe in Jesus have been sent by Him to share His good news with others. In my last post I said that one of the easiest ways to do this is simply to be honest. As an example, I talked about one of my friends in college, a man named Lance who, though he was a new Christian and not especially articulate, nevertheless had many opportunities to share his faith because he was honest about it.

Nevertheless, many Christians hold back. I’ve found two main reasons why. The first I’ll discuss in the post; the second will be the focus of my next post.

First, some are afraid that if they attempt to speak with others about Christ, they will botch it up. They fear that their lack of biblical knowledge will keep them from being effective, and even turn people further away from Christ. Certainly the more you know about the Bible, the better you’ll be able to explain the good news about Jesus. That’s one major reason to devote yourself to Bible study. But if sharing your faith is a matter of being honest, not winning arguments or hawking your spiritual wares, then you can tell people about Jesus without worrying about how little you know. In fact, many of the most effective “evangelists” are brand new Christians whose knowledge base is tiny, but whose enthusiasm for the Lord is contagious.

“But what should I do,” you might wonder, “if I get questions I can’t answer?” I once raised this very issue with Gary, my high school pastor at Hollywood Presbyterian Church. (Picture to right: The First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood)

“I’ll tell you what to do,” he said. “I’ll give you an answer that always works, every time.”

“I’ll tell you what to do,” he said. “I’ll give you an answer that always works, every time.”

“Wow! That would be great!” I replied, expectantly, but with a bit of skepticism. “How can I answer a question I don’t know how to answer?”

“It’s easy,” Gary continued. “Here’s what you say: ‘I don’t know.’ It’s really that simple.”

His advice shocked me. Somewhere along the way I had picked up the idea that I needed to have all the answers before beginning to talk with people about Jesus. In retrospect, I realize what a silly idea that was. But, at the time, Gary’s counsel set me free to be honest, not all-knowing. Since that conversation with Gary, I have probably said “I don’t know” more than thousand times when talking with people about Jesus. I have found that my willingness to admit my lack of knowledge, far from turning people away from Christ, often encourages them to be more open. They seem to trust me more if I freely confess my theological limitations.

I should add, however, that I will often follow the admission “I don’t know” with an offer: “But I’d be glad to try and find out for you.” The questioner usually feels honored that I’m willing to do research on his or her behalf, and it’s easy to pick up the conversation about Jesus at another time. Moreover, I get the chance to learn something of real value. There are abundant resources available – books, articles, tapes, leaders – to help us formulate solid, biblical answers for any question a person might ask.

My friend Lance, so free in talking about Jesus yet so limited in his knowledge, kept saying “I don’t know” until both he and his non-Christian friends became a bit frustrated. So he decided to take advantage of the relationships he had with other Christians in our dorm. He asked me and a mutual friend, John, if we would be willing to meet with his friends for a bull session about Christianity. John and I were thrilled because we loved to share our faith with people, but weren’t quite as forthcoming as Lance, even though we knew more than he did about the faith.

I’ll tell you what happened in that meeting in my next post in this series.

Topics: Mission | 3 Comments »

Sent to Proclaim the Good News, Part 2

By Mark D. Roberts | Monday, June 4, 2007

Part 8 of series: The Mission of God and the Missional Church

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

In my last post in this series, I began to explain how Jesus has sent His followers into the world to proclaim the good news. This is one main reason He has filled us with His Holy Spirit. Traditionally, Christians describe this task by the word “evangelism,” an English version the Greek verb that means “to tell good news.” But something gets lost in translation for many of us, since the word “evangelism” can fill us with dread rather than joy. The idea of “proclaiming good news” or “evangelizing” conjures up images that don’t fit most of us, and terrify many of us. We may picture Billy Graham preaching to crowded stadiums. Or we may envision the rainbow-haired man at the Super Bowl, holding up a placard with “John 3:16″ emblazoned upon it. Or we may fear that sharing Christ with others requires us to approach strangers, no matter how shy we may be. (Picture to right: Rollen Stewart, the original “rainbow-hair” evangelist.)

Unquestionably, God calls certain Christians to special ministries of evangelism. I am eternally grateful for the work of Billy Graham, whose preaching led me to faith in Christ. But I am not called to be Billy Graham, and neither are you, I’d imagine. You and I are called, however, to tell the good news of Jesus in a way that reflects our talents, personalities, and spiritual endowments.

Unquestionably, God calls certain Christians to special ministries of evangelism. I am eternally grateful for the work of Billy Graham, whose preaching led me to faith in Christ. But I am not called to be Billy Graham, and neither are you, I’d imagine. You and I are called, however, to tell the good news of Jesus in a way that reflects our talents, personalities, and spiritual endowments.

How shall we do this? In fact it’s much simpler and less scary than it might seem. Are you ready for one key to proclaiming the good news of Jesus? Here is it: Just be honest! Or, as my mother used to say to me, just be yourself! Talking with people about Jesus doesn’t depend upon your mastery of a sales pitch. In fact, the less you “sell” Jesus the better. But as you honestly share your life, your convictions, your hopes, even your doubts and fears, with those around you, the good news will inevitably and naturally emerge.

I think, for example, of a college friend named Lance. He was a brand new Christian when I met him in my dorm at Harvard. Lance was a brilliant engineer, but not especially adept at verbal communication. In fact, he was rather shy and awkward. But Lance simply talked about his faith as if it were a normal part of his life. Imagine that! If he was on his way to a Bible study and a roommate asked, “Where’re you going?” Lance would tell the truth. Unlike some of us, he wouldn’t try to hide his Christian activity by saying, “Oh, I’m off to some meeting” and leave it at that. Nor would he use his roommate’s question as invitation to start preaching, “I’m going to a Bible study and so should you, unless you want to burn in Hell.” Rather, Lance would simply say, “I’m on my way to a Bible study.” Before long, his roommate would ask why he went to the study. Again, Lance would be honest: “Because I am a Christian and I want to know more about the Bible.” Pretty soon Lance and his roommate would be talking comfortably about Christ – no hype, no salesmanship, no terror, just honest communication. All of this could have happened, of course, with mere human ability. But remember that Lance was also empowered by the Holy Spirit, who gave him courage and helped him to speak truly about Jesus.

When we realize that “proclaiming the good news” doesn’t require us to do something that terrorizes us, but merely to be honest, many of the barriers to personal evangelism fall down. But I find many Christians hesitant to share their faith in Christ for two additional reasons. I’ll address those in my next post in this series.

Topics: Mission | No Comments »

Sunday Inspiration from Pray the Gospels

By Mark D. Roberts | Sunday, June 3, 2007

Today is Trinity Sunday in the Christian Year

Excerpt

“Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.”

Matthew 28:19

Click here to read all of Matthew 28:16-20

Prayer

Dear God, on this Trinity Sunday, we remember Your wondrous and mysterious nature as one God in three persons. Even as we confess this truth and believe it, we admit that we cannot fully grasp it. It exceeds our comprehension and leads us to wonderment.

All praise be to You, God the Father, for Your love that pursues us and runs to welcome us home to You.

All praise be to You, God the Son, for Your faithfulness in giving Your life for us and our salvation.

All praise be to You, God the Spirit, for dwelling within and among us, so that we might be Your people.

All praise be to You, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, for Your glory and grace!

Postscript

The Gloria Patri

Glory be to the Father,

and to the Son,

and to the Holy Ghost.

As it was in the beginning,

is now,

and ever shall be,

world with out end.

Amen.

Amen.

A classic 15th century icon of the Trinity by Rublev

Topics: Sunday Inspiration | 1 Comment »

Week in Review: May 27 - June 1, 2007

By Mark D. Roberts | Saturday, June 2, 2007

My Recent Blogging

Sunday, May 27: Inspiration from Pray the Gospels

Monday, May 28: Memorial Day Gratitude

Tuesday, May 29: Sent by Jesus to Continue His Mission

Wednesday, May 30: Sent in the Power of the Spirit

Thursday, May 31: Amazed . . . and Wondering

Friday, June 1: Sent to Proclaim the Good News, Part 1

Links to Other Sites

The Pope’s Jesus. Check out Scot McKnight’s series of review posts on the Pope’s new book on Jesus.

Ben Witherington on Billy Graham. A moving post by one of my favorite scholars about one of my favorite people.

The Word in Community. Tod Bolsinger has a reflective piece on reading the Scripture – all of it! – with his church.

YouTube Success

In April my daughter and I went to Sea World in San Diego. Apart from the animal features, Sea World offers several fun rides, the most of exciting of which is Journey to Atlantis.

In April my daughter and I went to Sea World in San Diego. Apart from the animal features, Sea World offers several fun rides, the most of exciting of which is Journey to Atlantis.

While on the ride, I took a few pictures and some video, which I turned into a short clip and then posted it on YouTube. It has become by far the most popular of my several YouTube videos, with almost 5,000 viewings. Watch out, Steven Spielberg, here I come. (I’ll bet he’s worried, too.)

Topics: Week in Review | No Comments »

Sent to Proclaim the Good News, Part 1

By Mark D. Roberts | Friday, June 1, 2007

Part 7 of series: The Mission of God and the Missional Church

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

Like Jesus, we have been sent to proclaim the good news. In addition to telling His disciples to wait for the Spirit to empower them, Jesus explained what the Spirit’s power would accomplish:

When the Holy Spirit has come upon you, you will receive power and will tell people about me everywhere — in Jerusalem, throughout Judea, in Samaria, and to the ends of the earth (Acts 1:8).

Even as the Spirit came upon Jesus in His baptism to anoint Him for preaching the good news of the kingdom of God, so the Spirit empowers us to spread the good news about Jesus. Notice that the content of our good news is a revised version of Jesus’s own message. Whereas He proclaimed the coming of God’s reign, we bear witness to Jesus Himself, to what He accomplished in His life, death, and resurrection. We have the privilege of announcing to people that Jesus died for their sins so that they might be reconciled to God and therefore live forever under God’s reign, both in this life and in the life to come. Our good news is more than: “You can go to heaven when you die.” It is “You can be reconciled to God right now. You can begin to experience true fellowship with the God by living under God’s reign because of what Jesus has done for you” (see 2 Cor 5:16-21).

The language of the kingdom of God, so embedded within Jewish culture and Old Testament theology, can easily confuse us today. But this is nothing new. It was also confusing for non-Jewish people in the Roman world, the very people to whom Jesus sent His disciples with the good news. Therefore, the early Christians developed other ways to communicate the gospel so that their hearers might understand and respond in faith. Rather than announcing that the kingdom of God had come through Jesus, they proclaimed Him as Savior and Lord. The salvation and sovereignty of God’s kingdom was now expressed with emphasis upon the salvation and sovereignty of Jesus. Same basic reality – new language!

This modified language, which also has its roots in the Old Testament, retains its power in our world today. Most of us became Christians because we realized that we needed Jesus to be our Savior, the one who delivers us from our sins and reconciles us with God. By trusting in Jesus, we also accepted Him as Lord, the rightful ruler of our lives. Thus, through embracing Christ as Savior and Lord, we were reconciled to God and entered into the kingdom of God as His subjects, even if we had not yet heard those precise words. (Picture to the right and below: The television characters of the Lone Ranger and Tonto)

In American culture, the good news of Jesus as Lord and Savior has lost some of its original meaning. One of the most powerful cultural forces in our country is individualism. We glorify the “rugged individualism” of our heroes, Lone Rangers who defeat the forces of evil all by themselves. (Though even the so-called Lone Ranger had his Indian companion Tonto! But think of more recent heroes such as Rambo.) When the message Jesus as Lord and Savior gets pressed through the image of individualism, the result is a partial gospel: Jesus died for my sins so I can have a relationship with Him and go to heaven when I die. Now this is true, but not complete. Jesus also died for the sins of the world. And God’s intention is not just to get us to heaven individually, but to form us into a transformed community that will be used by God to help transform this world.

In American culture, the good news of Jesus as Lord and Savior has lost some of its original meaning. One of the most powerful cultural forces in our country is individualism. We glorify the “rugged individualism” of our heroes, Lone Rangers who defeat the forces of evil all by themselves. (Though even the so-called Lone Ranger had his Indian companion Tonto! But think of more recent heroes such as Rambo.) When the message Jesus as Lord and Savior gets pressed through the image of individualism, the result is a partial gospel: Jesus died for my sins so I can have a relationship with Him and go to heaven when I die. Now this is true, but not complete. Jesus also died for the sins of the world. And God’s intention is not just to get us to heaven individually, but to form us into a transformed community that will be used by God to help transform this world.

Thus, many Christians today are discovering that the gospel of the kingdom of God communicates more fully in our culture. It calls us, not only to personal faith in Jesus, but also to be part of His kingdom community and to join Him in His work of recreating the world.

Other Christians maintain the central message of Jesus as Savior and Lord, but make sure these terms retain their original, biblical flavor. Jesus as Savior not only saves individuals for life after death, but also is bringing wholeness to people, families, societies, and the whole world. Similarly, Jesus is not only my personal Lord, but also the Lord of the World, the One before whom every knee will one day bow. Thus the good news of Jesus matters, not just to individual souls, but to families, businesses, churches, and even nations.

Topics: Mission | No Comments »

Amazed . . . and Wondering

By Mark D. Roberts | Thursday, May 31, 2007

I just did something I’ve done many times before. It shouldn’t have been a big deal. I expect many of my readers will be unimpressed, and will wonder why I’m so amazed, and why I’m wondering. So let me try to explain.

Yesterday, while at a friend’s house, I heard the soundtrack from the movie Schindler’s List. Composed by John Williams, and featuring the sublime violin solos of Itzhak Perlman, the music is deeply moving. Hearing it also reminded me of many scenes from the film, which is one of the most emotionally powerful movies I have ever seen.

Ever since I heard the soundtrack, I haven’t been able to get it out of my mind. So a few minutes ago I sat down at my computer, visited the iTunes website, found and then downloaded the music (for only $9.99). A quick transfer to my iPod, and now I’m listening to this fantastic album. (You can order this album in the “old-fashioned” way by clicking here and getting it from Amazon.)

Ever since I heard the soundtrack, I haven’t been able to get it out of my mind. So a few minutes ago I sat down at my computer, visited the iTunes website, found and then downloaded the music (for only $9.99). A quick transfer to my iPod, and now I’m listening to this fantastic album. (You can order this album in the “old-fashioned” way by clicking here and getting it from Amazon.)

I’ve done this sort of thing many times before. I’m not a novice when it comes to music downloads. I never did the Napster thing, but I’ve dropped a good chunk of change through iTunes.

So why am I amazed by what I just did? And why am I wondering?

I’m amazed because, for some reason, I was able to step back and see my actions from a bit of a distance. Usually I take for granted the downloading of music. But, for some reason, today I see differently.

For most of human history, people didn’t even have the ability to record sound. The first phonograph was invented by Thomas Edison only 130 years ago (November 21, 1877). Listening to sound recordings became popular in the 1920s, with the invention of vinyl disc records. LPs (long-playing records) came along in the 1930s. The 20s also featured the invention of magnetic tape (reel to reel) for recording and playing back sound. This technology received a huge popular boost in the 1960s because of the invention of the 8-track tape ten years earlier. In 1963 Philips introduced the cassette tape. Two decades later, in late 1982, Philips and Sony released the first music on Compact Disc (CD). As you can see, all of this is fairly recent in human history.

But all of these fine technologies had certain limitations. If you wanted to listen to a song, you had to physically go and purchase it from a store. If the album you were seeking wasn’t current (as in the case of Schindler’s List, which is 14 years old), chances are you wouldn’t find it in most record stores. You might get lucky in a used record store. Or you might have to order it and wait several days. Even ten years ago, if I wanted to own a copy of the Schindler’s List CD, I might have to spend several hours to find it.

Then, in 1999, Napster came along, allowing computer users to download huge amounts of music for free. Naturally, this raised legal challenges, since it amounted to stealing copyrighted material. While the record industry wrung its hands and fought Napster in court, Apple got busy, introducing iTunes in 2001 along with its fantastically popular iPod. As they say, the rest is history. In April of this year Apple announced that it had sold over 100 million iPods. By this time users had downloaded over a billion songs!

Today it took me no more than ten minutes to locate and download the album. That’s why I’m amazed. What a time savings! What a convenience! What a luxury!

Why am I wondering? I’m wondering about how this newfangled expediency will, over time, impact my soul, and our corporate soul. I’m not big on delayed gratification. I want what I want, and I want it now. And when it comes to music, I can pretty much get what I want when I want it. Is this good? It’s surely pleasant and convenient. But is it good? Or is there something ennobling about having to wait, even to purchase a piece of music? Would I appreciate having the Schindler’s List soundtrack more if I had to invest more effort to get it? Or am I morally better off because I have been able to listen to this transcendent recording for the last two hours rather than driving to a record store in what might have been a fruitless search?

As you can see, I’m not preaching here, just wondering. As a lover of technology and convenience, I think iTunes is just swell. And Amazon. And Google. And all of their online friends. Ironically, as I was writing this blog post, my wife wanted me to purchase a couple of CDs for a friend for his birthday. So I did, in about five minutes, thanks to Amazon.) But what happens if we begin to think all of life should be so instantaneous and serviceable. What if we expect our spouses to be like this? Our children? Our churches? Even our God?

So I’m both amazed and wondering. And I’m delighting in the Schindler’s List soundtrack, which I highly recommend, no matter how you choose to get it.

Tomorrow I’ll get back to my “mission of God” series.

Topics: Musings | 13 Comments »

Sent in the Power of the Spirit

By Mark D. Roberts | Wednesday, May 30, 2007

Part 6 of series: The Mission of God and the Missional Church

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

In my last post I showed that Jesus sent His followers into the world to replicate His own mission of making disciples. We who follow Jesus are to make more followers of Jesus.

It’s easy to accept our charge to do the ministry of Jesus without really thinking about what we’re doing. “OK,” we might say, “That’s just fine. We’re to do the ministry of Jesus. Great!” But when we stop and think about it, we have accepted an astounding and overwhelming mission, one that is seemingly impossible. If we take seriously our sending by Jesus to do His work, our hearts should pound and our knees should knock. How, in heaven’s name, are we to do what He did? Given our manifest human limitations, not to mention our sinfulness, how can we do the works of the divine Son of God?

Doing the ministry of Jesus is a bit like climbing Mt. Everest. This mountaineering adventure is so demanding that it almost exceeds human capabilities. The vast majority of people who attempt to climb Everest never make it to the top. The physical challenges associated with scaling this peak include miles of strenuous hiking, thousands of feet of climbing, negotiating glaciers and treacherous ice fields, and fighting the most extreme weather conditions on earth. Perhaps most difficult of all is the lack of oxygen near the summit of the mountain’s 29,028 feet. This region is called “the Death Zone” because of the harrowing conditions, especially the dearth of oxygen. If you and I were flown to the summit of Everest right now, we would pass out in a few minutes, and die shortly thereafter. There simply isn’t enough oxygen there to keep our bodies working.