| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

The Force of Freedom:

The Political Theology of George W. Bush

in his Second Inaugural Address

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2005 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com. Thank you.

The Political Theology of George W. Bush

Part 1 of the series "The Force of Freedom"

Part 6 of the series “A Rolling Stone Gathers No . . . Bible?”

Posted at 10:20 p.m. on Sunday, January 30, 2005

This series began as the end of another series: "A Rolling Stone Gathers No . . . Bible?" I started in commenting on Rolling Stone magazine’s refusal to print an ad for a Bible, when, suddenly, Rolling Stone reversed ground and accepted the ad. My efforts to make sense of this strange turn of events led me to the Rolling Stone website, where, lo and behold, I discovered a provocative blog entry that accused the President of smuggling Jesus into his second inaugural address. My last post in this Rolling Stone series was an analysis of the flawed logic of this blog entry. Yet I also suggested that blogger Tim Dickinson was on to something, even though what he actually wrote missed the point.

Let’s return to the conclusion of Mr. Dickinson’s blog post:

I'm no theologian. I don't claim to understand exactly what Bush is doing here. I only know enough to be creeped the f*** out. What's clearly evident here is Bush's messianic streak, front and center. I don't know if Bush sees himself as an agent of God spreading liberty in Jesus' name. Or whether he actually aims to spread Christianity, in the guise of liberty. Either way I'm not happy about it. [Note: asterisks are mine; original contained “uck”.]

I give Dickinson credit – truly – for admitting that he isn’t a theologian and that he doesn’t understand what Bush is doing here. I think if he had a little more theological background he would be less “creeped out.” At any rate, I want to deal with a couple specific claims.

Dickinson’s Claim: “What’s clearly evident here is Bush’s messianic streak, front and center.”

I assume Dickinson is using “messianic” with a popular, not a technical meaning. His point, I suppose, is that President Bush sees himself in some way as the world’s God-ordained savior. Yet as I read the second inaugural speech, I don’t see the slightest hint that George W. Bush seems himself as any sort of messiah figure.

But one could find evidence for a slightly different point, namely, that President Bush sees a “messianic” role for the United States of America. Let me quote four passages from his address, with certain phrases italicized for emphasis:

Advancing these ideals [of human dignity and value] is the mission that created our Nation. It is the honorable achievement of our fathers. Now it is the urgent requirement of our nation's security, and the calling of our time.

So it is the policy of the United States to seek and support the growth of democratic movements and institutions in every nation and culture, with the ultimate goal of ending tyranny in our world.

All who live in tyranny and hopelessness can know: the United States will not ignore your oppression, or excuse your oppressors. When you stand for your liberty, we will stand with you.

By our efforts, we have lit a fire as well - a fire in the minds of men. It warms those who feel its power, it burns those who fight its progress, and one day this untamed fire of freedom will reach the darkest corners of our world. |

|

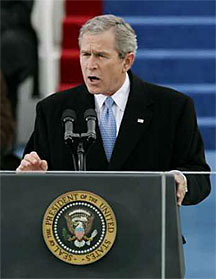

| |

President Bush delivering his second inaugural address |

One could say that the President sees America as having a unique and crucial calling in this time of history, a national messiahship, if you wish. Yet he steps back from saying clearly that God has specifically appointed the United States to this task:

We go forward with complete confidence in the eventual triumph of freedom. Not because history runs on the wheels of inevitability; it is human choices that move events. Not because we consider ourselves a chosen nation; God moves and chooses as He wills. We have confidence because freedom is the permanent hope of mankind, the hunger in dark places, the longing of the soul.

The President’s point seems to be, not that God has chosen the United States per se for the task of spreading freedom throughout the world, but rather that the United States, by acting on the side of freedom, as put itself on God’s side.

Dickinson’s Claim: “I don't know if Bush sees himself as an agent of God spreading liberty in Jesus' name. Or whether he actually aims to spread Christianity, in the guise of liberty. Either way I'm not happy about it.”

This is curious. I can see why Dickinson would be unhappy if President Bush were seeking to spread Christianity in the guise of liberty. I actually heard someone allege that the President had America invade Iraq for the purpose of opening up the country to Christian evangelism. This particular speaker thought it was a good idea to use American military might to that end, I might add. But if this were the case, Dickinson wouldn’t be the only one unhappy with the President’s subterfuge. Many Christians would join him, including me.

Yet let’s suppose for a moment that President Bush “sees himself as an agent of God spreading liberty in Jesus’ name.” So, believing himself to operate under the authority of Jesus and as an agent of God, the President is about the business of spreading liberty throughout the world. Would that really be so bad? One might be unhappy with his belief that he is an agent of God, I suppose. But his purpose – to spread freedom throughout the world – would surely be a good one. I think Mr. Dickinson needs to work out his happiness issues with a little more precision. In one case he thinks the President is acting deceitfully, spreading Christianity while pretending to spread liberty. In the other case he thinks the President has strange motives, but surely Dickinson would approve of what the President is trying to do on the basis of these motives.

I don’t believe, however, that President Bush sees himself as “an agent of God spreading liberty in Jesus’ name.” From what he said in his second inaugural address, and from what he’s said elsewhere, I think it would be more accurate to say that the President “sees himself as called by God to lead the United States to spread liberty throughout the world, doing this not in the name of Jesus, but in the name of freedom and liberty.” In fact, here's how President Bush ended his speech (before the conventional “God bless America” part):

America, in this young century, proclaims liberty throughout all the world, and to all the inhabitants thereof. Renewed in our strength - tested, but not weary - we are ready for the greatest achievements in the history of freedom.

Although Dickinson fears that President Bush is really thinking of Jesus when he speaks of freedom, I don’t find evidence of this, either in the second inaugural, or in his other speeches and writings. I think, in fact, George W. Bush sees freedom itself in an almost mystical light. At one point he says, for example,

History has an ebb and flow of justice, but history also has a visible direction, set by liberty and the Author of Liberty.

Notice, the direction of history has been set not only by “the Author of Liberty,” as any biblically-oriented Christian would affirm, but also by liberty itself. In the second inaugural, in this passage and elsewhere, the President has imbued freedom with powers that seem divine. Dickinson made this point, though I think he rather botched the implications.

In my next post I want to work on some more sensible implications, as I continue to examine the political theology of George W. Bush.

Religious Imagery in the Second Inaugural

Part 2 of the series “The Force of Freedom ”

Posted at 8:30 a.m. on Tuesday, February 1, 2005

In my last post I began to examine the political theology of President Bush as it was laid out in his second inaugural address. In this post I will continue that examination.

I realize, of course, that some people won’t take the President at his word. No matter what he actually says about religion and its relationship to governing, they’ll allege that he has a hidden agenda. Of course he may have such an agenda. But, in my opinion, the conversation about George W. Bush’s faith has been influenced far too much by gossip and innuendo – both on the right and on the left. Secularists, like Rolling Stone blogger Tim Dickinson, see Jesus hiding behind the President’s rhetoric when he’s really not there. And evangelicals, longing for the President to act on their social agenda, often try to read the divine handwriting on the wall, only to find out it’s just graffiti. (In fact, I think the President’s words and actions point out that he doesn’t have a hidden religious agenda – a point of frustration for those who wish he had one.)

I was startled yesterday when TIME magazine arrived. The cover proclaims: The 25 Most Influential Evangelicals. One of the subtitles reads: “What Does Bush Owe Them?” Turning quickly to this article (link works for subscribes only), I found in the first paragraph a reference to the second inaugural address. Let me reproduce part of that paragraph here:

For people of faith, the political landscape has never been entirely comfortable terrain. Politics, they have learned from experience, is a process in which principles get ground up into compromises—or ignored until the next campaign rolls around. This time religious conservatives are counting on things to be different: churchgoers mobilized as never before and helped re-elect a President they see as one of their own. Now they expect him to deliver for them. The early signals from President George W. Bush have been mixed. Bush's Inaugural Address brimmed with religious imagery, but abortion was the only top priority of the Christian right that he mentioned, in a fleeting and oblique reference near the end. He congratulated the tens of thousands of abortion foes who marched in Washington last week on the gains they made during his first term but promised nothing concrete in his second.

|

|

|

The theme of this paragraph carries throughout the article: that politically-conservative Christians have a big agenda for President Bush, though initial signs of his willingness to push their agenda have been disappointing to them.

This, TIME declares, was the case with the second inaugural address. Though it “brimmed” with religious imagery, nevertheless the speech offered little explicit support for the social agenda of the Christian right. (This fact alone should help Tim Dickinson to be less “creeped out.” But it should “creep out” James Dobson, Gary Bauer, and other politically-conservative Christian activists.)

I want to pause a moment to consider the claim that the President’s speech “brimmed” with religious imagery. I did not hear the speech live. Before I read it, I heard commentators right and left touting or bemoaning the religious character of the speech -- lots of “brimmed with religious imagery” comments, love it or leave it. So when I actually sat down to read the speech, I was expecting something on the order of a sermon. Yet my expectations were not fulfilled. Though religious imagery is present in the second inaugural, it is hardly filled with it. Here are the religious images from the speech:

After the shipwreck of communism came years of relative quiet, years of repose, years of sabbatical - and then there came a day of fire.

From the day of our Founding, we have proclaimed that every man and woman on this earth has rights, and dignity, and matchless value, because they bear the image of the Maker of Heaven and earth.

Now it is the urgent requirement of our nation's security, and the calling of our time.

We will persistently clarify the choice before every ruler and every nation: The moral choice between oppression, which is always wrong, and freedom, which is eternally right.

Eventually, the call of freedom comes to every mind and every soul.

The rulers of outlaw regimes can know that we still believe as Abraham Lincoln did: "Those who deny freedom to others deserve it not for themselves; and, under the rule of a just God, cannot long retain it."

By our efforts, we have lit a fire as well - a fire in the minds of men. It warms those who feel its power, it burns those who fight its progress, and one day this untamed fire of freedom will reach the darkest corners of our world.

Self-government relies, in the end, on the governing of the self. That edifice of character is built in families, supported by communities with standards, and sustained in our national life by the truths of Sinai, the Sermon on the Mount, the words of the Koran, and the varied faiths of our people. Americans move forward in every generation by reaffirming all that is good and true that came before - ideals of justice and conduct that are the same yesterday, today, and forever.

And we can feel that same unity and pride whenever America acts for good, and the victims of disaster are given hope, and the unjust encounter justice, and the captives are set free.

We go forward with complete confidence in the eventual triumph of freedom. Not because history runs on the wheels of inevitability; it is human choices that move events. Not because we consider ourselves a chosen nation; God moves and chooses as He wills. We have confidence because freedom is the permanent hope of mankind, the hunger in dark places, the longing of the soul. When our Founders declared a new order of the ages; when soldiers died in wave upon wave for a union based on liberty; when citizens marched in peaceful outrage under the banner "Freedom Now" - they were acting on an ancient hope that is meant to be fulfilled. History has an ebb and flow of justice, but history also has a visible direction, set by liberty and the Author of Liberty.

May God bless you, and may He watch over the United States of America.

I’ll accept the fact that some of these passages are religious only in the broadest sense (lighting a fire or a reference to the soul). But, even given my generous inclusion of anything remotely religious, all of these passages above make up only 22% of the President’s speech. The italicized words constitute only 4% of the speech. In my opinion, that’s hardly brimming.

I’m belaboring this point, with percentages to boot, to illustrate a tendency among commentators – both secular and Christian – to exaggerate the President’s religiosity. If you want to read a second inaugural address that actually is brimming with religious images and ideas, check out Abraham Lincoln’s. (For an outstanding treatment of the religious themes in Lincoln’s second inaugural, see the fine book by Ronald C. White Jr., Lincoln’s Greatest Speech.)

Of course simply the fact that a President employs religious imagery tells us little about his actual political theology. One can use religious imagery in decidedly non-religious ways, of course. For example, the following sentence contains an obvious biblical allusion:

Americans move forward in every generation by reaffirming all that is good and true that came before - ideals of justice and conduct that are the same yesterday, today, and forever.

The phrase, “the same yesterday, today, and forever” is a quotation from a New Testament document, the Letter to the Hebrews (13:8). Very biblical, I must say. Yet, context is everything here when it comes to meaning. The President is talking about the permanence of the ideals of justice and conduct. Hebrews makes a different point: “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever.” Now there’s a telling difference, don’t you think?

This example suggests the need to examine more closely what the President actually said about religion and politics in his speech, and how he actually used religious imagery. I will begin to do this in my next post.

What Breaks the Power of Hatred?

Part 3 of the series “The Force of Freedom”

Posted at 7:45 a.m. on Tuesday, February 2, 2005

In my last post I reproduced and commented upon the political imagery in President Bush’s Second Inaugural Address. I ended by noting that the presence of religious imagery in this speech doesn’t necessarily mean the speech was itself religious. This conclusion depends upon an analysis of the actual use of religious imagery and themes in the speech. This is what I propose to investigate today (and in future posts).

For example, early in the speech the President said:

For a half century, America defended our own freedom by standing watch on distant borders. After the shipwreck of communism came years of relative quiet, years of repose, years of sabbatical - and then there came a day of fire. (emphasis added)

There seems to be a biblical allusion here. This was pointed out by Tim Dickinson in the Rolling Stone blog post that led me into this whole discussion of the Second Inaugural. Dickinson actually sees “years of sabbatical” as a reference to the Old Testament idea of the Sabbath year, but this makes little sense. “Day of fire” does, however, have biblical roots. Dickinson connects this phrase specifically to 1 Corinthians 3:13: “[T]he work of each builder will become visible, for the Day will disclose it, because it will be revealed with fire, and the fire will test what sort of work each has done.” In fact many biblical texts associate the Day of the Lord with the fire of God’s judgment (for example, Malachi 3:2). |

|

| |

Double Bad News

It was double bad news this 119th Groundhog Day. For one thing, Punxsutawney Phil saw his shadow on Gobblers Know in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania. This means we’ll have six more weeks of winter. But, as you can see in this picture, the other piece of bad news was that Phil actually tried to bite his official handler, Bill Deeley. Does this mean six more weeks of biting cold? I’m not sure. (Pic from Yahoo/Reuters ) |

Yet what exactly did the President mean by using the phrase “day of fire”? Dickinson sees plenty behind these three words: “In Bush's history, 9/11 becomes an apocalyptic test of Christian mettle, perhaps even a sign of the End of Days.” Yes, “day of fire” functions as a poetic way to describe the tragic events of 9/11. But there’s no evidence from the speech to suggest the apocalyptic scenario envisioned by Dickinson. A more reasonable conclusion is that the President was using biblical imagery in a fairly non-theological way to dramatize the horror of 9/11. His point was that this was a wake-up call to America, not a sign of the Apocalypse.

Immediately following “day of fire” we find this paragraph in the Second Inaugural:

We have seen our vulnerability - and we have seen its deepest source. For as long as whole regions of the world simmer in resentment and tyranny - prone to ideologies that feed hatred and excuse murder - violence will gather, and multiply in destructive power, and cross the most defended borders, and raise a mortal threat. There is only one force of history that can break the reign of hatred and resentment, and expose the pretensions of tyrants, and reward the hopes of the decent and tolerant, and that is the force of human freedom. (emphasis added)

This is one of those places in the speech where Tim Dickinson read between the lines and saw none other than Jesus himself. Here’s what Dickinson wrote in his blog:

"There is only one force of history," our president proclaimed, "that can break the reign of hatred and resentment, and expose the pretensions of tyrants, and reward the hopes of the decent and tolerant, and that is the force of human freedom."

Call me crazy, but there's another force to which I've heard people of Bush's ilk ascribe these same exalted powers of salvation. That force usually goes by the name of

Jesus.

As one who is of Bush’s ilk (an evangelical Christian) I would agree with Dickinson’s basic point. In a sermon I could very well say:

There is only one force of history that can break the reign of hatred and resentment, and expose the pretensions of tyrants, and reward the hopes of the decent and tolerant, and that is the force of Jesus [or, God’s kingdom made manifest in the person of Jesus, or God’s love in Christ].

Though I’m not so sure about Jesus being a reward for the hopes of the decent and tolerant, I do in fact believe there is only one force in history that can break the reign of hatred and resentment in our world. That is the force of Jesus, who ushers in God’s kingdom, and who exemplifies and embodies the power of God, which is love. The love of God in Christ is the only force powerful enough to destroy hatred and resentment.

How does Jesus put an end to hatred? On the one hand, he calls us to stop hating. We should love even those whom consider our enemies:

“You have heard that it was said, ‘You shall love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I say to you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be children of your Father in heaven” (Matthew 5:43-45).

If the people of the earth would follow Jesus’s imperative here, hatred would surely be on the wane.

But merely calling people to love isn’t enough to break the power of hate. The real smashing of hatred happened when Jesus died on the cross. I realize that we (both Christians and others) tend to think of Jesus’s death as bringing about personal salvation alone. But, from a biblical perspective, that’s just the start. In Ephesians 2, for example, the death of Christ on the cross is seen as that which forges reconciliation between between people:

But now in Christ Jesus you who once were far off have been brought near by the blood of Christ. For he is our peace; in his flesh he has made both groups into one and has broken down the dividing wall, that is, the hostility between us. (Eph 2:13-14)

Ephesians is speaking specifically of the conflict between Jews and Gentiles. But the broader point is clear, both from this text and many others: the end of hatred and hostility – peace among people -- comes only through the cross of Jesus, and through calling people to respond to God’s love as it is communicated through the cross.

Returning to the President’s speech, he did not say that Jesus is the only force in history that can break the reign of hatred. He said “that is the force of human freedom.” Drawing upon what he said in the rest of the speech, I take the President to mean that the actions of free people (especially the United States) combined with the yearning of all people for freedom will ultimately break the power of hatred in our world. Yet he seems to imbue freedom itself with a sort of mystical power, the power that the Bible assigns to God alone as God acts through Christ.

This leads Tim Dickinson to the improbable and unprovable conclusion that the President was really talking about Jesus in his speech. The more obvious and likely conclusion is that he was really talking about freedom, but assigning to freedom the power that Scripture assigns to God alone. To put the matter even more bluntly, in what he said about the power of freedom, the President was not in fact speaking from an evangelical Christian perspective, or even a biblical one.

Now I realize that he was speaking as the secular President of a secular nation. And I also realize that political leaders often make hyperbolic statements about freedom in order to inspire us to greatness. If President Bush had, in his Second Inaugural, said that the only power that can break the reign of hatred is the power of God in Christ, this would have been inappropriate. I would have joined his critics.

But I would have agreed with his theology. From a biblical perspective, what the President actually said about freedom was not correct. If one of my associate pastors, in a sermon preached in my church, were to say that the force of freedom is the only power that can overcome hatred, that pastor would be visiting my supervisory woodshed in a jiffy. I’d send that pastor back to do more biblical homework.

I am not doubting the President’s faith or his basic evangelical theology. But I do find his statement about freedom to be inconsistent with biblical theology. It actually sounds a whole lot more like classic theological liberalism. No wonder the President’s evangelical supporters get confused!

I’m my next post I’ll examine a couple other passages from the Second Inaugural.

Where Should Our Confidence Lie?

Part 4 of the series “The Force of Freedom”

Posted at 10:00 p.m. on Wednesday, February 3, 2005

In my last post I examined George W. Bush’s confidence in the force of freedom as it was expressed in his Second Inaugural Address, noting that he assigned to freedom that which Scripture attributes to God alone. Today I will look at two other passages in which the President exalted human ideals in striking language.

The first passage comes from the middle of the address, just after President Bush had spoken of America’s allies throughout the world. To the citizens of the U.S. he said:

Our country has accepted obligations that are difficult to fulfill, and would be dishonorable to abandon. Yet because we have acted in the great liberating tradition of this nation, tens of millions have achieved their freedom. And as hope kindles hope, millions more will find it. By our efforts, we have lit a fire as well - a fire in the minds of men. It warms those who feel its power, it burns those who fight its progress, and one day this untamed fire of freedom will reach the darkest corners of our world.

The fire-rhetoric here is rich, though I’m not quite sure whether I like it, or whether it is too much over-the-top. Nevertheless, we see once again the President’s confidence in the power of freedom. Nothing, in the end, will stop its progress throughout the whole world.

This vision is not to be found in the Bible. Moreover, it clearly is not consistent with a more apocalyptic vision for the future, in which things get worse until Christ comes to make them eternally right. Though the President’s personal faith is solidly evangelical, and though he borrows apocalyptic imagery from Scripture (fire, for example), his view of human progress is much more robust than that which is found among the majority of evangelicals today. As I mentioned in my last post, President Bush’s notion of the power of freedom reminds me of liberal Christian rhetoric from the last century. It sounds like the hopes of those who once believed that human effort could bring in the kingdom of God. It doesn’t sound at all like the eschatological scenarios of the New Testament, which reverberate throughout the sanctuaries of conservative Christianity.

Toward the end of the speech the President said this:

In America's ideal of freedom, the public interest depends on private character - on integrity, and tolerance toward others, and the rule of conscience in our own lives. Self-government relies, in the end, on the governing of the self. That edifice of character is built in families, supported by communities with standards, and sustained in our national life by the truths of Sinai, the Sermon on the Mount, the words of the Koran, and the varied faiths of our people. Americans move forward in every generation by reaffirming all that is good and true that came before - ideals of justice and conduct that are the same yesterday, today, and forever.

The call to personal integrity and self-government is badly needed in our time of history. The President believes that “the edifice of character” necessary for self-rule is sustained in our country by a multiplicity of religious traditions, including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, “and the varied faiths of our people.” This is surely true, to a point. But lumping all religions together in this way seems curiously simplistic. Could it be that some of the “varied faiths” of our people in fact work against the kind of self-government that is needed for freedom to thrive? I wonder.

Again, I see the President making the kind of religiously generic statement that Presidents of the United States often make. Yet a person would be hard pressed, I think, to defend this viewpoint from Scripture. Again, I’m not suggesting that President Bush should have spouted evangelical theology from his secular pulpit, but I am pointing out that his public proclamations are hard to reconcile with biblical faith.

This is even more evident in the final sentence of the paragraph I cited above. Here the President spoke of “ideals of justice and conduct that are the same yesterday, today, and forever.” In a previous post I mentioned that this last phrase – “the same yesterday, today, and forever” -- is an obvious quotation of Hebrews 13:8. That verse reads: “Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today and forever.”

I would not expect the President to quote this verse in an inaugural address. Nor would I approve of his doing so. Yet it seems odd to me that he felt comfortable using this distinctive biblical description of the timelessness of Jesus Christ when talking about “ideals of justice and conduct.” Is it really true that such ideals are timeless in the same way that Jesus Christ is timeless? I rather doubt it. The President’s idealism in this instance seems much more Platonic than Christian. (Plato, you may recall from your college philosophy class, believed in the existence of transcendent forms or ideals, which were timeless and independent of human perception.)

An evangelical Christian President finds himself in an extraordinary difficult position. He needs to speak to a diverse nation in ways that are not too Christian. He needs to inspire a people with a vision that is not too biblical. President Bush is, after all, the President of the United States, not the national pastor. It also makes sense to me that he would draw inspiring language from the Bible. Yet some of his rhetorical flourishes make me uncomfortable, not as an American citizen, but as a Christian theologian. I’m not sure that Scripture allows me to share President Bush’s confidence in the power of human freedom. And I’m quite sure I wouldn’t be able to refer to human ideals as “the same yesterday, today, and forever.” From a biblical perspective, this sort of timelessness belongs to Christ alone.

Am I getting too picky? Perhaps. Should I just chalk up the biblical allusions in the Second Inaugural to customary presidential hyperbole? Maybe. But I am concerned that the President’s language will ultimately backfire. No, I do not share the fears of Rolling Stone blogger Tim Dickinson and other secularists that the President will impose Jesus upon the nation. If anything, I think the rhetoric of the Second Inaugural shortchanges Jesus, and not the other way around. |

|

|

Above: Raphael's "School of Athens" fresco in the Vatican library. A majestic image of classic philosophy.

Below: An enlargement of the two figures in the center of Raphael's vision, Plato and Aristotle. Plato, on the left, points upward to the eternal forms/ideals that are the basis of his philosophy, while Aristotle gestures in a earthly direction. |

|

But, even beyond this concern, I am worried that by assigning divine powers to human ideals and aspirations, President Bush is forging impossible expectations. Freedom may well advance throughout the world, and I hope it does. But as long as human beings remain captive to sin, new forms of oppression will emerge. And if we expect human ideals to be universal and timeless, then we’ll be shocked when these ideals crumble beneath the weight of human evil. We won’t know how to respond when human beings callously and joyously murder innocent people. The confidence of the President in freedom and human idealism seems to be inconsistent with the reality of a fallen humanity and a broken world.

This is not to say that Americans should back away from the fight for freedom. Far from it. But our fight often involves far more ambiguity than clarity. Moreover, we do battle for what is right, not because we are certain that right will prevail this side of heaven, but because it is right to seek righteousness and justice now, no matter what the results may be.

Tomorrow I will examine one last paragraph from the Second Inaugural, the paragraph that, in my opinion, is the most theologically pregnant of the whole speech.

The Eventual Triumph of Freedom?

Part 5 of the series “The Force of Freedom”

Posted at 11:30 p.m. on Thursday, February 3, 2005

With this post I’ll continue my examination of President Bush’s political theology as expressed in his Second Inaugural address. Tomorrow I’ll finish up my study of this address. But the series won’t end tomorrow because just this morning the President gave another speech with clearly religious themes. This was at the Annual National Prayer Breakfast in Washington D.C. So, after wrapping up my examination of the Second Inaugural tomorrow, I’ll examine the theology of the prayer breakfast speech to see what, if anything it adds to our understanding of the political theology of George W. Bush.

Here is the second to the last paragraph in the Second Inaugural Address:

We go forward with complete confidence in the eventual triumph of freedom. Not because history runs on the wheels of inevitability; it is human choices that move events. Not because we consider ourselves a chosen nation; God moves and chooses as He wills. We have confidence because freedom is the permanent hope of mankind, the hunger in dark places, the longing of the soul. When our Founders declared a new order of the ages; when soldiers died in wave upon wave for a union based on liberty; when citizens marched in peaceful outrage under the banner "Freedom Now" - they were acting on an ancient hope that is meant to be fulfilled. History has an ebb and flow of justice, but history also has a visible direction, set by liberty and the Author of Liberty.

This is full of theologically tantalizing ideas. It’s also the only place in the whole speech, other than a quotation from Lincoln and the customary “God bless you” closing, where the President used the word “God.” Elsewhere God was spoken of more artfully, or perhaps more indirectly, as “the Maker of Heaven and Earth” and “the Author of Liberty.” (“Maker of Heaven and Earth,” by the way, is a biblical title [see Gen 14:19-22; Psa 134:3]; “Author of Liberty” comes, not from Scripture, but from the third verse of “America” [My country, ‘tis of Thee]). It is interesting that in a speech touted or criticized as highly theological, God is only referred to five times, including the quotation from Lincoln and the closing benediction.

Let’s look closely at what the President said in this pregnant paragraph.

“We go forward with complete confidence in the eventual triumph of freedom.” We’ve seen this sort of confidence before. It pervades the entire Second Inaugural. And, as I’ve suggested earlier, it’s hard to find biblical support for this idea, unless, of course, by “freedom” one means “the true freedom that comes when God’s kingdom is fully established.” But I rather doubt that this is what the President intended to convey in this speech. Rather, he truly believes that freedom will ultimately prevail on earth. I wish I could join him in his certainty, but, on the basis of my reading of Scripture, such sureness is not forthcoming.

Let’s see what evidence the President sets forth for his “complete confidence in the eventual triumph of freedom” – “Not because history runs on the wheels of inevitability; it is human choices that move events.” Okay, so President Bush is not a determinist who believes that future events are already in some way set in concrete. Human choices “move events,” which means that we have the ability and responsibility to see that freedom advances. Wrong choices will lead to less freedom.

“Not because we consider ourselves a chosen nation; God moves and chooses as He wills.” This seems like an intentional echo of Abraham Lincoln’s own Second Inaugural. There, noting that both North and South prayed for victory in the Civil War, Lincoln observed, “The prayers of both could not be answered. That of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has His own purposes.” Of course behind Lincoln’s affirmation of God’s sovereignty lies the biblical idea of God, of Whom it could be truly said that he “moves and chooses as He wills.” In fact, many scholars believe that the very name of God (Yahweh) means, in a sense, that God is a self-determining agent. So in the statement “God moves and chooses as He wills,” the President stands squarely on the solid foundation of biblical theology. |

|

| |

This is an actual photograph of Lincoln delivering his Second Inaugural address. The President is in the red circle. Ironically, in the black circle is John Wilkes Booth, who later assassinated Lincoln. |

Yet I find this whole sentence odd. The second part about God’s sovereignty seems to qualify or even to contradict the idea that we consider ourselves a chosen nation. Yet one could very well argue that the God who “moves and chooses as He wills” has in fact moved and chosen the United States to be the agent of liberation in our world today. Given everything else President Bush said about freedom and America’s role as the guarantor of freedom, I would have expected him to say, “God moves and chooses as he wills, and for his purposes he has chosen the United States in this time of history to secure freedom for all people throughout the world.” Or something like that. I would be surprised if the President did not believe that God has chosen America for this role of bringing freedom to the world, especially given what he had said in an earlier paragraph:

From the day of our Founding, we have proclaimed that every man and woman on this earth has rights, and dignity, and matchless value, because they bear the image of the Maker of Heaven and earth. Across the generations we have proclaimed the imperative of self-government, because no one is fit to be a master, and no one deserves to be a slave. Advancing these ideals is the mission that created our Nation. It is the honorable achievement of our fathers. Now it is the urgent requirement of our nation's security, and the calling of our time. (my emphasis)

It has been our national “mission” to advocate human dignity and fight for self-government. Now it is “the calling of our time.” Calling from whom? The most obvious and sensible answer is: from God. So I wonder why the President backed away from saying that God has in fact chosen America for a special, freedom-securing calling in our world. Does this just sound too religious?

In tomorrow’s post I’ll finish my examination of Second Inaugural, focusing on why exactly the President has such confidence in freedom, and asking whether this confidence is warranted.

Beware the Wet Blanket!

Part 6 of the series “The Force of Freedom”

Posted at 10:20 p.m. on Friday, February 4, 2005

Yesterday I continued my examination of President Bush’s political theology by looking at one paragraph near the end of his Second Inaugural. Today I want to revisit that paragraph, which I’ll print here to save you from having to scroll to find it:

We go forward with complete confidence in the eventual triumph of freedom. Not because history runs on the wheels of inevitability; it is human choices that move events. Not because we consider ourselves a chosen nation; God moves and chooses as He wills. We have confidence because freedom is the permanent hope of mankind, the hunger in dark places, the longing of the soul. When our Founders declared a new order of the ages; when soldiers died in wave upon wave for a union based on liberty; when citizens marched in peaceful outrage under the banner "Freedom Now" - they were acting on an ancient hope that is meant to be fulfilled. History has an ebb and flow of justice, but history also has a visible direction, set by liberty and the Author of Liberty.

The President has “complete confidence in the eventual triumph of freedom,” not because he advocates historical determinism or divine election, but because he sees freedom as having mystical, almost semi-divine characteristics. Freedom is “the permanent hope of mankind” and even the “longing of the soul.” Once again President Bush uses a biblical expression with a non-biblical usage. In the Psalms, “the longing of the soul” is for God and God’s presence. Consider, for example, the beloved beginning of Psalm 42:

As a deer longs for flowing streams,

so my souls longs for you, O God.

My soul thirsts for God, for the living God.

When shall I come and behold the face of God? (Psalm 42:1-2)

The biblical picture of the soul’s longing for God doesn’t mean, of course, that our souls don’t also long for freedom. This may very well be true. But I’m struck once again by the tendency of President Bush to speak of freedom in ways Scripture reserves for God alone. |

|

| |

Two elk near a flowing stream in Yellowstone National Park |

The final sentence of the paragraph I cited above combines freedom and God in a peculiar way. History “has a visible direction, set by liberty and the Author of Liberty.” As a biblically oriented Christian, I would certainly affirm that God, as the Author of life, has determined a direction for history. But I wouldn’t speak liberty and God in parallel, assigning to both the power to direct history.

Of course the President is trying to walk a fine line between his personal beliefs as an evangelical Christian and his public pronouncements as the President of the United States. If he said merely that history has a direction determined by God, this would be offensive to many who don’t hold this religious view. So by adding liberty into the mix, the President dulls down the clarity of his theology. Yet in so doing he runs the risk of making statements that are incompatible with his personal theology, not to mention with Scripture itself.

Why does President Bush have complete confidence in the ultimate victory of freedom? He offers two main reasons:

1. The hope and hunger for freedom “is meant to be fulfilled.” (By whom? See #2.)

2. History is flowing in the direction of more freedom, and this flow has been “set” by liberty and God.

God, and liberty as a power separate from God, are driving history in the direction that it must ultimately go. The precise details are not predetermined, the President advised, but are the results of human choices. Yet ultimately the force of freedom will prevail. President Bush has faith that, ultimately, all people will be free.

I believe this last statement. Someday all people will be free. Yet as a biblical theologian I cannot endorse the idea that this universal freedom will come because human beings made right choices and fought for freedom. The powers that bind humanity will not be defeated through human will or effort, but only through the power of God. Ultimately the world and its peoples will be set free from bondage, but only as God’s kingdom comes in all of its fullness. From a biblical point of view, true freedom comes through Christ, and Christ alone. As Jesus himself said in John 8:36: “So if the Son makes you free, you will be free indeed.”

Once again, I hasten to add that I would not have wanted President Bush to say this in his Second Inaugural Address. But I find that what he did say about freedom, however positive and visionary it might sound, is inconsistent with a biblical understanding of human nature and human history. I hate to be the one to throw a wet blanket on the President’s “untamed fire of freedom,” but I just don’t think his vision of freedom’s ultimate victory is consistent with biblical revelation. (For that matter, I’d argue that history itself shows us that for every advance of freedom there is a parallel advance of oppression. When the Berlin Wall tumbled down, we thought freedom had prevailed. Little did we realize that before long the twin towers of the World Trade Center would also tumble down as a new threat to human freedom emerged on the world stage. If we are ever able to put Islamic terrorism to rest, another threat to freedom will surely emerge.)

I want to conclude with something I have mentioned before in this series. Though I do not believe we can have confidence in the ultimate victory of freedom this side of the eschaton, I do believe it is right to seek freedom, not only for ourselves, but also for others. Christians line up on the side of the Great Liberator, the One who came to set the captives free. And even though we know that ultimate liberation will come only in God’s future, nevertheless we are to work in this world to secure the freedom of others. We don’t do this because we’re sure of victory in this life, however. We do it because we’re sure that it is right, whether or not our efforts prevail.

I find President Bush’s use of biblical language and themes in the Second Inaugural to be oddly unbiblical. If I did not know from other sources that George W. Bush is a strong evangelical Christian, I would think that he embraces mushy liberal Protestantism, with a huge helping of civil religion mixed in. I expect that his unusual combination of evangelical personal faith and a secular faith in freedom helps to explain why so many people are confused about President Bush’s “faith agenda.” Evangelicals often get their hopes up when George W. Bush speaks as an orthodox Christian, only to see them dashed on the reality of his presidential actions (and inactions). Liberals and secularists fear that the President is going to impose his Christianity upon them, taking away their freedom rather than augmenting it, when in fact his actions and his agenda rarely point in this direction, if ever.

I sense an unsettled inconsistency in the President’s mix of faith and politics. His political theology, it seems to me, is awkwardly conceived and expressed. Yet I appreciate the President’s effort to bring faith and politics together. He rightly understands that the world is not divided by some insurmountable barrier, with religion on one side and politics on the other. Some Christians have argued for this view, while many have lived it out. Yet this sort of division of the universe is completely antithetical to the biblical understanding of reality, in which God is both creator of and sovereign over all things, including nations and rulers. Politics is a matter for faith; and faith must be worked out in political actions. Yet this is much more easily said than done. I will confess that I find it much easier to criticize President Bush's effort than to advise him on how to do a better job integrating his faith with politics.

In my next post in this series I’ll take a close look at the speech President Bush gave last Thursday morning at the Annual National Prayer Breakfast. As of this moment, I’ve given that speech a very cursory reading. It will be interesting to see if anything in that address confirms or disconfirms what I’ve been arguing in this post. Stay tuned. . . .

Life Can Be Strange

Part 7 of the series “The Force of Freedom”

Posted at 10:20 p.m. on Sunday, February 6, 2005

Sometimes life can be strange. This year’s Super Bowl proved to be a decent football game, and the halftime show featured a fully dressed 62-year-old man who can actually sing! The commercials were predictably entertaining, and this year only one (by my count) could be considered in poor taste for family viewing. (By the way, the IFLIM website has almost all of the Super Bowl ads online. You can enjoy your favorites over and over again. Or maybe not. You get to choose.)

But the strangest part of my evening came after the Super Bowl. It was followed by an episode of The Simpsons, in which Homer ended up producing a Super Bowl halftime show. A subplot of the episode involved Homer’s neighbor, Ned Flanders, who, as a conservative Christian, was offended by sexually suggestive material on television. Ned began making movies of Bible stories, focusing on some of the most violent and bloody. The slap at Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ was obvious, though clever enough to be relatively inoffensive. In the end, Ned and Homer collaborated on the halftime show: a biblical extravaganza telling the story of Noah and the Ark. Of course the audience hated Homer’s show. One woman complained that she’d been trying to raise her children as good secular humanists and now, because of Homer, they were interested in religion. Count on The Simpsons to take everyone down a peg: over-zealous Christians, amoral athletes, pro sports, and the rest of American society as well.

I know Christians who are offended by The Simpsons, and I’m sure this episode provided one more occasion of offense. But if you look beyond the obvious irreverence, the program actually raises issues that we might want to think about. Why are we so easily bugged by sexual innuendo, but not by excessive violence? (I’m not excusing the sexual part, just wondering why we tolerate violence.) Why do we so often fail to communicate the good news of God in a way that the world can actually hear? Why do real, well-intentioned Christians so often come off like Ned Flanders? |

|

|

Homer Simpson even talks to God sometimes. I haven't watched enough to know if he's ever been to a civic prayer breakfast.

|

|

After The Simpsons the Fox Network ran a preview of a program that will begin to air in May. It’s called American Dad. A cartoon like The Simpsons, American Dad features Stan Smith, an over-zealous CIA agent, and his odd family. From a few minutes of observation, I found American Dad to be must less clever than The Simpsons and much more obviously crude. (When shows like this lack creativity they make it up with potty talk.) But one scene made me laugh, even though its final punch line has been overdone.

|

|

In this scene, President Bush received a phone call from God. (Yes, the white-haired, bearded old man in the sky.) God was calling to ask the President to cut down on his references to the Almighty in his speeches. When President Bush asked for an example, God said something like, “When you make comments like ‘God wanted me to be president,’ that would be something you ought to just keep to yourself.’” Before their conversation finished, however, God got interrupted by another call. “It’s Cheney,” he said, “I gotta take it.”

Okay, the “Cheney’s-the-boss” schtick has been overdone, though this may be the first suggestion that the Vice President is God's boss as well. Nevertheless, I had to chuckle at the dialogue between God and the President. Plus, if you’ve been following this blog series about the President’s political theology, you’ve got to admit this is quite a coincidence. I’ve been examining the President’s political religiosity and suggesting that he might want to reconsider how he uses “God-talk” in political speeches. It seemed strange to find some of my thoughts echoed in an inane cartoon. Of course this strangeness might encourage me to reconsider some of my thoughts! |

The question of how faithful Christians should speak of their faith in the political arena is a timely and tricky one. I took a couple of stabs at answering this question in last year’s blogging (see the series The Church and Politics in America and also Presidential Election Results: A Christian Response.) But my own thinking is still in process about this issue.

Of course it’s a lot easier for me to take time to reflect upon such things when I’m not a political candidate or government official. My forays into the public sphere have impressed upon me the difficult challenge of speaking about issues of faith in civic contexts. A few years ago I was invited to offer a prayer in a city prayer breakfast. “Prayer breakfast” was rather a misnomer, however, though we did eat breakfast. It was really more of a civic-religion fest, as well as a chance for political leaders to show a bit of religiosity and religious leaders to bask in their fifteen minutes of civic fame. Although several religious leaders from the community were invited to offer prayers that morning, I was the only one who simply prayed. Every other leader prefaced his prayer with a preface that was far too long, in my opinion. But I found it quite difficult, even in a designated prayer gathering, to know exactly how to pray. I wanted to include those gathered in my prayer, to lead in prayer, not just to pray. And I didn’t want to offend needlessly. Yet I also needed to pray in a way that was consistent with my faith and evangelical theology.

I can’t tell whether my effort was successful or not. I had mixed feelings about what I did, to be honest. Mostly I realized that such civic-religious overlaps are awkward. I did receive a number of positive comments, however, from people who appreciated the brevity of my prayer, and the fact that I didn’t add a sermonette as well.

Speaking of prayer breakfasts, in my last post I had promised to examine President Bush’s recent address at the National Prayer Breakfast. I’ll do that in tomorrow’s post, unless I watch another cartoon on television that sparks some blogging creativity. But, given the fact that I almost never watch television, the odds are that I’ll get back to the President tomorrow.

Prayer and Pancakes

Part 8 of the series “The Force of Freedom”

Posted at 10:20 p.m. on Monday, February 7, 2005

In this series I have offered a critical analysis of George W. Bush’s political theology as it appeared in his Second Inaugural address. Today’s post is an addendum of sorts, in that I will focus, not on the Second Inaugural, but on the President’s remarks at the National Prayer Breakfast that was held in Washington D.C. last Thursday, February 3, 2005. “Remarks” is an appropriate description of the President’s contribution, because he used just under 900 words, one-quarter of which were opening thanks and jokes. Among the remarks, a few are worthy of comment.

| “This morning reminds us that prayer has always been one of the great equalizers in American life. Here we thank God for his great blessings in one voice, regardless of our backgrounds.” The President rightly assumes that most Americans pray at one time or another, though his statement leaves out those who don’t. There is a sense in which all people who pray are “equalized,” in that we all humble ourselves before some deity (except for those whose “prayer” is actually meditation rather than communication). But I think the “one voice” idea, however nice it sounds, rather ignores the extent to which people throughout America pray differently, including those gathered for the prayer breakfast, with widely differing perceptions of the god to whom they pray, if they’re even praying to a god at all. I wish the President had stayed with the “equalizing” theme, stressing common humility rather than “one voice” unity. The National Prayer Breakfast, after all, is a thoroughly ecumenical event, including a wide variety of religious people, not just Christians, or even Christians and Jews. |

|

| |

President Bush praying at the National Prayer Breakfast. If he peeks even once, the whole world will know! |

“We recognize in one another the spark of the Divine that gives all human beings their inherent dignity and worth, regardless of religion.” Ouch! This is my least favorite line among the President’s remarks. I guess he means that when we pray with people of different religions we “recognize the spark of the Divine” in them. My problems with this notion are several. First of all, I’m not sure it’s true. I have prayed with non-Christian people in ecumenical gatherings and I haven’t seen a tiny bit of God in them so much as I have sensed our common need for God. Second, “the spark of the Divine” isn’t a Christian notion. In fact, this language finds its happy home in Gnosticism, the classic heresy that infected early Christianity, and continues to do so today. I don’t think the President is a Gnostic, of course. But I sure wish he’d avoided such unfortunate terminology. The President would have been much better served here by the language he employed in the Second Inaugural: “From the day of our Founding, we have proclaimed that every man and woman on this earth has rights, and dignity, and matchless value, because they bear the image of the Maker of Heaven and earth.” This statement makes more or less the same point as the “divine spark” comment but in a solidly biblical way. (Doesn’t it seem like the President should have his speeches vetted by a theologian who could catch obvious errors?)

“Through fellowship and prayer, we acknowledge that all power is temporary, and must ultimately answer to His purposes.” The President is in the ballpark here, but hasn’t yet found his seat for the game. We pray to God, in part because we recognize that his power is supreme and endless, not temporary. So “all power” is mistaken. The President’s point seems to be that prayer reminds us that all human power is subordinate to God, even accountable to him. Yet you can see in the President’s statement an effort, even in a so-called prayer breakfast, to avoid talking too much about God. It would have been better if he had said, “Through prayer, we acknowledge that all human power is limited [or subordinate or granted by God], and we who have such power must answer to God for our use of that power.” Though I’m quibbling about the words, I think the main idea here is both correct and profound. When we bow together before God in prayer, we experience our relative powerlessness and recognize God’s superior power and authority.

“For prayer means more than presenting God with our plans and desires; prayer also means opening ourselves to God's priorities, especially by hearing the cry of the poor and the less fortunate.” In the middle of his remarks President Bush veered away from talking about prayer, and focused instead on service, especially service rendered to the needy by faith-based institutions. This theme took up almost all of the second half of the remarks. The President’s point that prayer is more than telling God what we want is a solid one and well worth making. When we pray we do indeed “open ourselves to God’s priorities.”

After giving examples of how religious organizations help the poor and needy throughout the world, President Bush added: “The America that embraced Veronica [a young refugee from Liberia who was helped by the Catholic Social Agency] would not be possible without the prayer that drives and leads and sustains our armies of compassion.” Prayer, from this perspective, has value because it motivates caring service. This, it seems to me, is a valid point, even if it isn’t prayer’s main purpose.

The President concluded his remarks in this way:

I thank you for the fine tradition you continue here today, and hope that as a nation, we will never be too proud to commend our cares to Providence and trust in the goodness of His plans.

This is surely a fine conclusion, though I find the President’s use of “Providence” odd, especially since he’s about to speak of the plans of Providence as “His plans.” Wouldn’t it have been stylistically better and more truthful to call God “God” rather than “Providence” in this line? Yes, I know that would sound very religious. But the President was speaking at a prayer breakfast, after all.

Perhaps I’m giving too much credit to the word “prayer” in the title “National Prayer Breakfast.” In a recent column, Gregg Easterbrook, who claims to be an orthodox Christians, began his rant with this line: “I pray for the end of the National Prayer Breakfast.” Easterbrook went on to give a bit of the history of this event and to suggest several possible reasons for his prayer that the breakfast be stopped. It has become, in Easterbrook’s view, little more than an opportunity for leaders to make a public demonstration of conspicuous religiosity.

Yet his main reason for hoping that the prayer breakfast will end may sound all too familiar. Easterbrook writes:

[W]hat shakes my faith about the National Prayer Breakfast is that Jesus forbid public prayer. . . . Here is Jesus's teaching on the subject of public prayer, from Matthew in the New Revised Standard:

Whenever you pray, do not be like the hypocrites; for they love to stand and pray in the synagogues and at the street corners, so that they may be seen by others. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward. But whenever you pray, go into your room and shut the door and pray to your Father who is in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you.

The Washington Hilton ballroom is today's equivalent of the "street corners" on which hypocrites used to pray "so that they may be seen by others."

Whether or not Easterbrook correctly applies the words of Jesus in this case, his point is surely worth serious consideration. I have never been to the Annual Prayer Breakfast, but I know several faithful Christians who have, and who believe it is a worthwhile event. I’d love to hear their response to Easterbrook (and to Jesus, for that matter).

In the end, whether Easterbrook is right or not, he does point to the difficulty involved in being a faithful disciple of Jesus and still an active participant in the secular world. And if such faithfulness is hard for you and me, just think how difficult it must be for President Bush. If nothing else, my examination of his political theology reminds me to pray for the President. I mean it. This man – a brother in Christ – needs my prayers, and yours too.

|