| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

All Things New

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2005 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com . Thank you.

A World of Stark Contrasts

Part 1 in the series "All Things New"

Posted at 11:55 p.m. on Sunday, January 2, 2005

We live in a time of stark contrasts. On the one hand, this last week was a time of celebration. We began the week with Christmas, a time to remember the birth of Jesus and to rejoice in the traditions of the season, both sacred and secular. At all of the Christmas Eve services at my church we sang:

Joy to the world! The Lord is come.

Let earth receive her King.

Let ev’ry heart prepared him room.

And heav’n and nature sing.

And heav’n and nature sing.

And heav’n and nature sing.

|

|

| |

The first of four Christmas Eve services at Irvine Presbyterian Church.

|

|

Yet as we were finishing up our Christmas dinners the next day, nature was singing another song, and it was a tragic tune indeed. At 4:58 p.m. PST on December 25th, an enormous earthquake rumbled beneath the Indian Ocean just off the coast of Indonesia. Initial damage from the 9.0 quake was great, but nothing compared with the catastrophic impact of the tsunami it created. Soon, surging walls of water pounded Southeast Asia, from Indonesia and Thailand to Sri Lanka and India. Even thousands of miles away in Africa over 100 lives were lost from the powerful tsunami. But that was nothing compared with the devastation closer to the epicenter of the quake, where well over a hundred thousand people died instantly, with millions homeless and facing desperate conditions in the aftermath of the tsunami. |

|

|

During this past week, our hearts have been gripped by stories and pictures of human suffering: mounds of rubble containing human corpses, the city of Banda Aceh in northern Indonesia virtually demolished, fathers weeping for lost children, children wandering aimlessly looking for parents they will never find. Even though most of us have not been directly touched by this tragedy, nevertheless we have been personally moved by the suffering of others.

And then we ended the week with New Year’s Eve, a traditional time of reveling, a chance to welcome the new year with toasts and kisses. Yet even in Times Square, where over a million people gathered for fireworks and other festivities, the crowd paused for a moment of silence to remember the victims of the tsunami. Similar displays of solidarity and sadness were seen throughout the world. |

|

| |

|

So we live in a strange times, a time of stark contrasts. Perhaps we remember the classic words of Ecclesiastes. There is:

|

a time to break down, and a time to

build up;

a time to weep, and a time to laugh;

a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

(3:3-5)

Yet in our crazy world, this is a time for all those things at once.

In time like this we can’t help but asking lots of questions, like: How can we even think of a new year when life is so tragic? And where is God in all of this tragedy? Does faith help us to make sense of the suffering on the shores of the Indian Ocean? Is there some cord that ties together the calamity in Southeast Asia, the turn of the new year, and God?

Yes, I believe there is, and it’s to be found in the 21st chapter of Revelation, verses 1-5. |

|

|

Revelation 21:1-5

While on the Island of Patmos, John had an extensive vision. Near the end of that vision he saw the future of the cosmos. Listen to what he describes:

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying,

“See, the home of God is among mortals.

He will dwell with them as their God;

they will be his peoples,

and God himself will be with them;

he will wipe every tear from their eyes.

Death will be no more;

mourning and crying and pain will be no more,

for the first things have passed away.”

And the one who was seated on the throne said, “See, I am making all things new.”

The Theological Foundation

God says, “See, I am making all things new.” To understand what this means, we need a solid theological foundation beneath our feet. I’d like to sketch out that foundation briefly, focusing on three main footings. The first I’ll examine today. The next two will be the subject of tomorrow’s post.

1. The Goodness of Creation

The first footing is the goodness of creation. We begin at the very beginning, when God created the heavens and the earth. Repeatedly Genesis 1 records God’s judgment that what he had made was good. Indeed, after he finished creating, God looked upon what he had made and saw that it was “very good” (Gen 1:31).

Biblical people believe in the fundamental goodness of creation. We believe that this world is imbued with divine value, that its goodness is to be enjoyed. Unlike many of the world’s philosophies and religions, we do not see this life as something to be tolerated at best, or as a mere stepping stone to the “great beyond,” or as something evil that we’ve got to reject in favor of a purely spiritual realm, or as something ultimately unreal that we must learn to transcend. Divine creation means that this life matters, that the creatures of this world matter, and that, most of all, human beings matter since we uniquely bear the image of God.

The fact that God will someday forge a new heaven and a new earth doesn’t impugn the core value of this present heaven and earth. In fact it underscores the eternal worth and goodness of creation. In the end, God won’t wipe out the universe and whisk us away to some spiritual realm. Rather, he will refashion this world so that it will finally be what God intended it to be from the first.

Of course when I speak of the goodness of creation, our hearts immediately want to object, “But what about the tsunami? How can we believe that creation is good when the natural world causes so much suffering?” I’ll pick up this question tomorrow.

The Brokenness of Creation

Part 2 of the series “All Things New”

Posted at 11:00 p.m. on Monday, January 3, 2005

Recap of yesterday’s post: Yesterday I began a new series, “All Things New.” At first I considered the stark contrasts of the last week, with the tsunami tragedy wedged in between celebrations of Christmas and New Years. Then I asked: How can we even think of a new year when life is so tragic? And where is God in all of this tragedy? Does faith help us to make sense of the suffering on the shores of the Indian Ocean? Is there some cord that ties together the calamity in Southeast Asia, the turn of the new year, and God? My answer: Yes, such a cord is to be found in the 21st chapter of Revelation, verses 1-5, which concludes with God saying, “See, I am making all things new” (21:5). Yet really to understand what God means, we need to stand on a solid theological foundation. The first footing of that foundation is the goodness of creation. I concluded yesterday’s post by asking: "But what about the tsunami? How can we believe that creation is good when the natural world causes so much suffering?" This is where we pick up today.

2. The Brokenness of Creation

The fact that God needs to make it new brings us to the next footing in our theological foundation: the brokenness of creation.

|

When we’re enjoying the beauty of nature, it’s easy to celebrate the goodness of creation. Two years ago my family and I spent two glorious weeks at Poipu Beach on the island of Kauai. Gorgeous sand, warm water, gentle tradewinds: it was just about perfect. No doubt about it, creation is good! |

|

My daughter frolicking in the surf of Poipu Beach

|

|

|

The beach at the Chedi resort on Phuket, an island in the Indian Ocean, part of Thailand.

|

But just a few days ago thousands of tourists were enjoying a similar paradise on the beaches of Phuket, Thailand, when all of a sudden everything changed. The ocean rose and crashed upon the pristine beaches and elegant resorts. All of a sudden, heaven became hell. Hundreds if not thousands of tourists lost their lives in a few moments of nature’s wrath. Creation good? Whom are we trying to kid? If God's creation is really good, why did a mammoth tsunami devastate the lives of thousands of tourists in Phuket, not to mention millions of innocent people all around the Indian Ocean?

|

We'll never be able to answer this question definitively. There is so much about this world, not to mention God's sovereignty, that we simply cannot understand. But one thing we know for sure is that this world, having been created good, is now broken. It doesn't work how it's supposed to work.

The root cause of the world's brokenness we find in Genesis 3, when the woman and man rebel against God. As a consequence, the earth that was to be their friend becomes both friend and enemy. The man will continue to harvest from the earth, but only in the midst of thorns and thistles. The woman will continue to give birth, yet with the pains of labor. |

|

|

From a biblical perspective, the woman is not the only one suffering the trauma of childbirth, however. Consider this passage from Romans 8:

I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory about to be revealed to us. For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God; for the creation was subjected to futility, not of its own will but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labor pains until now; and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies. (8:18-23)

Like a woman in labor, creation itself is groaning with pain and waiting for redemption. Now there is theological depth in this text that I can't begin to plumb in this post. But the point I wish to emphasize is clear: Creation itself is broken. Somehow human sin has infected, not only human hearts and human society, but also the very universe in which we live. The result of this infection is the sort of tragedy we have seen in the last week, with its consequent suffering. In truth, suffering goes on throughout our world every day. But when it comes so dramatically and unexpectedly, we must wonder why things are so horrible, and why, if God is good, he lets it all happen.

No matter how much the reality of suffering is a problem for Christian theology, not to mention for Christian sympathy, we must recognize that the Bible doesn't cover up the problem. On the contrary, Scripture is blunt when speaking of the brokenness of creation and the suffering this produces. Just read Job, or Habakkuk, or dozens of the Psalms. As Christians, therefore, we must never be surprised by suffering, or act as if terrible things just shouldn't happen in today's damaged world.

Please understand that I'm not implying we should be unmoved by suffering. Far from it! As God's people we ought regularly to pray the prayer of World Vision's founder, Bob Pierce: "May my heart be broken by the things that break the heart of God." Indeed, the more we are in touch with God's heart, the more we will share in the pain of others, and the more we will seek to alleviate that pain. My point today is that we should expect and be ready for suffering because it's an inescapable part of our broken world.

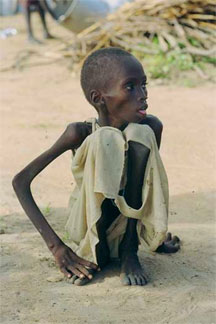

I don’t think there’s anyone around these days who would deny the brokenness of our world or turn a deaf ear to the cries of those who are suffering as a result of the tsunami. But, let’s face it, most people in North America live most of the time with relatively little awareness of human suffering throughout the world. For example, the death toll from the tsunami is currently at 150,000, and may very well become much, much higher. This is a tragedy of astounding proportions. But how many of us are aware that every year in the developing world about six million children die from hunger-related causes. This means that even if there had been no earthquake in the Indian Ocean, with all of its dire results, approximately 120,000 children would have died in the week that began with Christmas and ended with New Years Day – under ordinary conditions. Yet most of us would have lived with almost no awareness of this tragic reality.

Though the impact of the tsunami has been horrible indeed, perhaps it will open our eyes to the brokenness of the world and the anguish caused by this brokenness. Maybe this will motivate us, not only to respond with short term generosity to the immediate need around the Indian Ocean, but also to act with a consistent commitment to alleviate human suffering. I’ll have more to say about this later. |

|

| |

A child starving to death in the Sudan, one of thousands in this country alone.

|

So far I’ve outlined two of the footings of the theological foundation that helps us to understand God’s statement, “See, I am making all things new.” This claim makes sense in light of the goodness of creation and its brokenness. In tomorrow’s post I’ll examine the third and final footing in this foundation.

The Hope of the New Creation

Part 3 of the series “All Things New”

Posted at 11:55 p.m. on Tuesday, January 4, 2005

Recap of previous posts: I began this series by asking: How can we think of a new year when there is so much suffering in the world, epitomized by the tsunami tragedy? Is there some cord that ties together the calamity in Southeast Asia, the turn of the new year, and God? I responded that there is such a cord, and it is found in the 21st chapter of Revelation, where God says, “See, I am making all things new” (21:5). To understand this statement we need a solid theological foundation, which I’m outlining in three “footings.” Footing 1 was the goodness of creation. Footing 2 was the brokenness of creation. Today we get to the third footing: the hope of the new creation.

The Hope of the New Creation

As Christians we embrace the hope of the new creation. Even as we take the brokenness of this world and the pain it produces seriously, we don't give up hope and fall into the pit of despair. Let me return to Romans 8 so Paul can finish the thought he began earlier:

We know that the whole creation has been groaning in labor pains until now; and not only the creation, but we ourselves, who have the first fruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly while we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies. For in hope we were saved. Now hope that is seen is not hope. For who hopes for what is seen? But if we hope for what we do not see, we wait for it with patience. Likewise, the Spirit helps us in our weakness . . . . (8:22-26)

What is our hope? Not merely that we who know Christ will one day be in heaven with him, though this is a marvelous hope, to be sure. We will spend eternity with the Lord and with his people. But there is more. Our hope as Christians is that one day Christ and heaven will come to earth, that eternity will somehow embrace and transform our earthly reality.

This is the hope expressed in the vision of Revelation 21. Notice, God doesn't say, "See, I am taking all my people up to heaven." Rather, he says, "See, I am making all things new." The one who made all things in the first place will remake them. All things, now caught up in brokenness, will one day be repaired. They'll be as good as new, or even better.

What will this world be like when God makes all things new? The list of characteristics is a long one, indeed, an endless one. Let me share just a few of them. When God makes all things new:

• Tsunamis won't wipe out multitudes of people.

• Cruel despots won't murder millions of their own citizens.

• Trusted leaders won't abuse the innocent.

• The powerful won't victimize the powerless.

• Children won't die, leaving their parents with unbearable grief.

• Parents won't die, leaving their children as orphans.

• Bodies won't suffer with cancer, or HIV, or heart disease.

• and so on, and so on. . . .

When God makes all things new, then the earth will be just as he has intended it to be. In the classic vision of Isaiah 11:

The wolf shall live with the lamb,

the leopard shall lie down with the kid,

the calf and the lion and the fatling together,

and a little child shall lead them. . . .

The nursing child shall play over the hole of the asp,

and the weaned child shall put its hand on the adder's den.

They will not hurt or destroy

on all my holy mountain;

for the earth will be full of the knowledge of the LORD

as the waters cover the sea (11:6-9).

“As the waters cover the sea.” Now that's a sadly ironic image, is it not? And that is, of course, where the waters belong: in the sea, not the land.

When Isaiah speaks of the knowledge of the Lord, he's not referring only to knowing about God. Rather, he means that people throughout the earth will really know God: truthfully, personally, intimately. This notion is very close to John’s vision in Revelation 21 when he sees and hears God saying,

"See, the home of God is among mortals.

He will dwell with them as their God;

they will be his peoples,

and God himself will be with them;

he will wipe every tear from their eyes." (21:3-4)

So this is our hope, the hope that will not disappoint us. In his time, God will forge a new creation. In that day, we, along with "all things" will be made new.

If you’re inclined in a theological direction, you know that I’ve been talking here about eschatology, the doctrine of the end times (from the Greek eschaton, “end” and logos, “word, idea”). Although many Christians get fascinated by the prophetic visions of how the end will come – hence the popularity of the Left Behind series – we often underestimate the centrality of eschatology to Christian theology, and the extent to which this impacts the way we act each day. Living in light of the end, living eschatologically, is about far more than speculating on the rapture or the millennium or when Christ will return. Rather, it’s living in light of a perspective that transforms and guides our daily lives. |

|

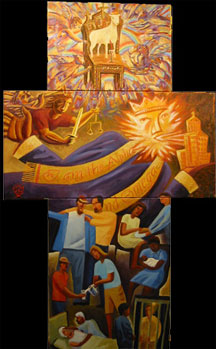

| |

" The Return" by James B. Janknegt. A profound vision of the end times. |

In my next post I’ll begin to talk about what this looks like in practice, with specific reference to how we respond to the present crisis surrounding the Indian Ocean.

Building on the Foundation: Living as People of Hope

Part 4 of the series “All Things New”

Posted at 9:55 p.m. on Wednesday, January 5, 2005

Recap: In the 21st chapter of Revelation God says, “See, I am making all things new” (21:5). To understand this statement we need a solid theological foundation composed of three footings: the goodness of creation, the brokenness of creation, and the hope of the new creation. In time, or rather at the end of time as we know it, God will “make all things new,” ushering in the new creation. This promise, far from being irrelevant eschatological mumbo jumbo, gives us a perspective by which to live each day.

In this post and in those that follow I want to examine further the implications of the new creation for how we live in the world – the real world in which multitudes of people are suffering as a result of the recent tsunami, not to mention other multitudes who are dying of hunger, disease, and poverty. Although some people see talk of a new creation as a kind of religious “happy-speak” that makes little difference in the world, in fact someone who grasps the import of Christian eschatology will live vigorously in this world rather than retreating from it into some sort of hyper-spiritual fairyland.

So then, let’s cut to the chase. If God will someday make all things new, how should we live today? |

|

Tsunami and Theology Links

Many bloggers and other writers have been commenting on the tsunami from a theological perspective. Much of what they have been writing is quite good. I’m going to link to a few examples. I may not agree with everything these folks say, of course, but their contributions are helpful and wise:

Tom Wright (as in N.T. Wright), “Meanings of Christmas: In the new world there will be no more sea.”

Tod Bolsinger, “Don’t ‘Just Do It’.”

Craig Williams, “On Suffering and What to Do”

Albert Mohler, “God and the Tsunami – Theology in the Headlines, Part One” (see other parts too).

Donald Sensing, “Tsunamis and the Presence of God” |

Living as People of Hope

First, and most obviously, if we believe in the new creation yet to come then we will live as people of hope. By hope I’m not speaking of wishful thinking, of yearning for something that will never come to pass. Though I might dream of playing professional basketball, it would be wrong to say I hope for this. I gave up that hope 33 years ago. Hope, especially in biblical perspective, includes the reasonable anticipation that something will actually happen. Christian hope is based upon the faithfulness of God. The One who has promised to make all things new will in fact do it. Hope, therefore, is confident yearning for something in the future.

Christian hope is not the same as a “Pollyana-ish” belief that things will always turn out for the best in this life. As a pastor I frequently find myself with people who are facing difficult times, such as a life threatening illness. Sometimes I observe others trying to cheer them up with such platitudes as, “Oh, I’m sure everything will be okay.” These cheerleaders mean well, but they really can’t be sure of what they promise. Often things in this life don’t turn out okay, at least in the short view. Yet we can have confidence that, in the end, God will establish his peace and justice throughout the renewed cosmos.

When we live with this hope in our hearts, we are set free from the despair that so easily engulfs people today. Yes, at times we’ll feel discouraged. Yes, we’ll face disappointment. But we won’t give up completely because we have genuine, trustworthy hope.

This hope can give us strength when we feel weak. It can sustain us when circumstances let us down. Let me offer a couple of illustrations by way of example.

Have you ever known a woman in the ninth month of pregnancy – or been one, for that matter? Such a woman feels lots of discomfort, if not outright pain. She has trouble sleeping, walking, and, well, you name it. Yet a woman in her last weeks of pregnancy is sustained, even energized by her hope: the hope that in just a few days her physical suffering will be over, and in its place she will have a lovable little baby. With such a hope a woman great with child can endure almost anything, even, by the way, the pain of labor and delivery. |

|

|

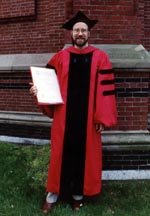

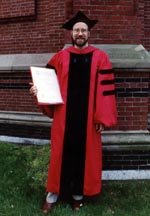

The other example comes from my own life. One of the hardest things I ever attempted in life was the writing of a dissertation. I’ll spare you the details, but suffice it to say the experience almost overwhelmed and defeated me, largely because I was trying to write a dissertation while working full-time and living 3,000 miles from my university.

|

In 1991 I left Hollywood Presbyterian Church to become pastor of Irvine Presbyterian Church. I took two months off between these two callings in order to finish my dissertation. During those eight weeks I worked ten, maybe twelve hours a day. It was grueling work. But I had come far enough to believe that my work would ultimately be rewarded. In time I would finish my dissertation and get my Ph.D. When I was exhausted and discouraged, I would think about the day when I’d receive my degree. I thought about the sense of relief and accomplishment I’d feel. A few moments of reverie would recharge my batteries. My hope of getting my doctorate gave me the strength to do the work required to earn it.

And so it is with our living in this world. The hope that God will someday make all things new keeps us going, even when the “oldness” of this present creation feels overwhelming. As the New Testament Letter to the Hebrews says, “We have this hope, a sure and steadfast anchor of the soul.” So when we feel buffeted by the pounding waves of this world, our souls tethered to a hope that keeps us centered in truth and moving forward in service. |

The moment of my escahtological hope

|

|

Yet Christian hope isn’t just an intellectual conviction. It’s also a matter of authentic Christian experience, and experience that is often connected with suffering. In Romans 5 the Apostle Paul writes:

Therefore, since we are justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ, through whom we have obtained access to this grace in which we stand; and we boast in our hope of sharing the glory of God. And not only that, but we also boast in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint us, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us. (Romans 1:1-5)

Notice that Paul is up front about the reality of our sufferings. Yet hope allows us to boast, to find genuine meaning and value even in these afflictions. Moreover, our hope does not let us down. Why? Why do we have such confident hope? “Because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us” (v. 5). In other words, our hope is connected to our present experience of God.

To this present experience I’ll turn in my next post.

Building on the Foundation: Living as New People Now

Part 5 of the series “All Things New”

Posted at 9:45 p.m. on Thursday, January 6, 2005

Recap: In the 21st chapter of Revelation God says, “See, I am making all things new” (21:5). To understand this statement we need a solid theological foundation composed of three footings: the goodness of creation, the brokenness of creation, and the hope of the new creation. The promise of the new creation, far from being theological trivia, gives us a perspective by which to live each day. As I explained in my last post, in light of this perspective we will live as people of hope.

Today I’ll explore another aspect of how we should live given God’s promise to make all things new.

Living as New People Now

As Christians we look forward to participating in the renewing work of God in the last day. When God makes “all things new,” this will include us too. In that time “we will be like [God], for we will see him as he is” (1 John 3:2). The “good work” God has begun in us will be completed “by the day of Jesus Christ” (Phil 1:6). Not only will we perceive God in his matchless glory, but also we will “be glorified with him” (Romans 8:17). Thus we have much to look forward to.

| Yet our eschatological hope does not give us the license to sit around and wait for the future to come. Some Christians throughout the centuries have pursued this course of behavior, especially when they were convinced that the return of Christ was imminent. For example, around A.D. 50 in the Macedonian city of Thessalonica, a group of Christians decided that since Jesus was coming soon, they might as well take it easy and rely on the charity of their Christian brothers and sisters. The Apostle Paul, writing in 2 Thessalonians, rebuked them for their laziness and exhorted them “to do their work quietly and to earn their own living” (2 Thess 3:12). |

|

| |

The Greek city of Thessaloniki today. I wonder if the Christians there are still lazy? Photo courtesty of HolyLandPhotos.org. |

Though the renewal of all things lies in the future, we begin to experience eschatological newness in this life. Consider Paul’s striking language in 2 Corinthians:

So if anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new! All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ . . . . (2 Cor 5:17-18).

This passage makes it clear that the new creation has already begun in Christ. Some Bible translations read verse 17 as “if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation.” But this underestimates the scope of the original language. The Greek literally reads, “Therefore if someone [is] in Christ, new creation!” “He is a new creation” is grammatically possible, but the Greek reads most literally, “Creation is new.” This obvious sense is backed up by the following claim, namely that “everything old has passed away” and “has become new.” When a person becomes a Christian, not only does that individual experience renewal, but also he or she begins to live in the new creation, in the world of the future.

Now I know it’s tempting to say at this point: “What wishful thinking! Clearly Paul was living in some sort of theological la-la land. Whom was he trying to kid?” But remember that this same Paul was the one who spoke of the sufferings of this present time and creation itself experiencing the pain of childbirth (Romans 8: 18-23, see Part 2 of this series). No wishful thinking here. So how can we make sense of this apparent contradiction? We must learn to think in terms of New Testament eschatology, in which God’s kingdom is here in part, but not completely. Theologians speak of the kingdom as “already and not yet” – it’s already here and, at the same time, not yet here. (If this seems like theological gobbledygook to you, let me recommend that you read parts 9-11 of a series I wrote on the message of Jesus.)

The point, then, is that Christians begin now to live in the new creation. We live with one foot in the present and the other foot in the future. Of course this suggests the practical question: How can we experience the new creation now?

First of all, we experience the new creation now through the presence of God’s Spirit. Consider another astounding passage from 2 Corinthians:

Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom. And all of us, with unveiled faces, seeing the glory of the Lord as though reflected in a mirror, are being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another; for this comes from the Lord, the Spirit (2 Cor 3:17-18).

|

We are being transformed now into the very image and glory of God. How? Through “the Lord, the Spirit.” The Holy Spirit enables us to experience in reality a bit of the life to come. When we are healed, guided, blessed, empowered, and transformed by the Spirit, we savor the aroma of the new creation.

Second, we live in the new creation when we join ourselves to the community of God, the fellowship of Christian people on earth. The Holy Spirit not only dwells in us individually, but among us corporately, thus making us together a veritable temple of God (1 Corinthians 3: 16). This is one reason why the church is so essential in today’s world. It is here that we get a true taste of heaven. In the fellowship of God’s people the future begins to break into the present. |

One of my favorite times of community, our Thanksgiving Eve service at church. In this picture my daughter is sharing her thanks with the congregation. |

|

One of the best statements of this reality, apart from what we find in Scripture itself, comes from The Lambeth Commission on Communion: The Windsor Report, 2004. This is the report that came out last October, ostensibly to deal with the crisis in the Anglican Communion over the issue of gay ordination. Yet the report doesn’t begin with that issue at all, but rather with a brilliant statement of the nature and purpose of the church of Jesus Christ. Let me quote an extended section here. The language is dense, but well worth the effort it takes to read it:

In particular, as the letter to the Ephesians puts it, God’s people are to be, through the work of the Spirit, an anticipatory sign of God’s healing and restorative future for the world. Those who, despite their own sinfulness, are saved by grace through their faith in God’s gospel (2.1-10) are to live as a united family across traditional ethnic and other boundaries (2.11-22), and so are to reveal the many-splendoured wisdom of the one true God to the hostile and divisive powers of the world (3.9-10) as they explore and celebrate the astonishing breadth of God’s love made known through Christ’s dwelling in their hearts (3.14-21).

In other words, in the church the future of God can be seen. The church is a sign to the cosmos of God’s new creation.

Now I’m well aware how terribly idealistic this sounds. Believe me, I know how far away from this ideal the church can be in reality. I’ve just had one of those weeks that a pastor dreads, dealing with lots of hurt feelings and anger in my flock. I’ve often felt both frustrated and discouraged. I’m not seeing much of the new creation these days. Yet here’s where the hope of the future keeps me going. I know that, in time, God will bring to completion what he has begun in my church, and this helps me to pursue what’s right even when I’m tired of trying.

I must add, however, that every now and then I have seen in the church the reality of the new creation yet to come. I’ve seen it when people who have offended each other nevertheless work out forgiveness and reconciliation. I’ve seen it when people freely sacrifice their possessions to care for others in need. I’ve seen it when people are healed through prayer. And I’ve seen it when racial and ethnic divisions are pierced by the cross of Christ, and former enemies become brothers and sisters in one family.

If you’re a member of a church, you might examine your own behavior in your fellowship. Are you living as part of God’s new creation? Or are you mired in the old? Furthermore, we who are church members, and even more so those of us who are church leaders, need to take a good, hard look at our congregations. Do they truly reflect the new creation yet to come? Or do they look a whole lot more like this current creation, mirroring its values, priorities, and prejudices? What can we do to embody the reality of the new creation, so that we might be “an anticipatory sign of God’s healing and restorative future for the world”?

In my next post I will try to answer this question.

Building on the Foundation:

Extending the Newness of God into the World

Part 6 of the series “All Things New”

Posted at 9:45 p.m. on Monday, January 10, 2005

| Note: Tomorrow I’ll begin a new series, a close examination of bunch of stories on happiness in this week’s TIME magazine. In particular, I want to examine TIME’s perspective on the role of religion in human happiness, and a column by David Van Biema entitled “Does God Want Us to Be Happy?” |

|

|

Recap: This series began with God’s promise in Revelation 21: “See, I am making all things new” (v. 5). After establishing a three-part theological foundation upon which we might understand the meaning of this promise, I have been exploring some practical implications for our lives today. I suggested that we should live as people of hope and as new people now. Today I want to consider how we might extend the newness of God out into the world.

Extending the Newness of God Into the World

Living as new people now isn’t a private, individualistic experience. Surely there are some Christians who keep their faith to themselves, hoarding the hope of the new creation. But that is not God’s intent.

In Romans 12, for example, the Apostle Paul is running through a laundry list of basic Christian dos and don’ts. In the middle of the list we find this collection: “Rejoice in hope, be patient in suffering, persevere in prayer. Contribute to the needs of the saints; extend hospitality to strangers” (12:12-13). Notice the juxtaposition here. We are to rejoice in hope as we remember the new creation yet to come. Yet in our broken world, we must be patient in the midst of suffering and keep on praying. These sound like they could be the stuff of private religiosity. But then, on the heels of hope, patience, and prayerfulness, we’re to reach beyond ourselves to care for others.

The Greek phrase translated as “contribute to the needs of the saints” implies a sharing in their difficulties, not merely dispassionate charity. This gets very close to the classic prayer of Bob Pierce, founder of World Vision, who frequently asked, “May my heart be broken by the things that break the heart of God.” We are expected, not only to be do-gooders in the world, but also to be people of genuine compassion.

The original language behind “extend hospitality to strangers” uses a vigorous verb, which in secular Greek could be used for chasing after the prey of a hunt. Paul’s phrase could be literally translated, “Eagerly pursue the love of strangers.” Once again, the picture is not of begrudging generosity, but of a passionate extension of God’s new life in tangible ways. |

|

| |

World Vision founder, Bob Pierce, with an Asian child |

As I have argued previously, hoping for the new creation doesn’t remove us from the world. Rather, it leads us into the world as people who share our hope with others. We do this, not only in words, but also in deeds of compassion and care.

Consider one other New Testament passage that offers of a vision of the future. This one comes from Jesus himself:

When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will put the sheep at his right hand and the goats at the left. Then the king will say to those at his right hand, ‘Come, you that are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.’ Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry and gave you food, or thirsty and gave you something to drink? And when was it that we saw you a stranger and welcomed you, or naked and gave you clothing? And when was it that we saw you sick or in prison and visited you?’ And the king will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.’ (Matthew 25:31-40).

Here is a scene of judgment in the end times, “when the Son of Man comes in his glory.” Its point is powerful. If in this life we care for the poor and the downtrodden, then Jesus, the kingly Son of Man, receives our efforts as if they were gifts to him. Once again we see that eschatology (our understanding of the end times) motivates ministry, especially the ministry of alleviating human suffering.

Let me cite one final New Testament passage that directs our living out into the world. In 2 Corinthians 5 we read: “So if anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation: everything old has passed away; see, everything has become new! All this is from God, who reconciled us to himself through Christ, and has given us the ministry of reconciliation” (5:17-18). I used this passage earlier in this series, focusing on the new creation yet to come. Now I want to zero in on the last thought, namely, that God has given us the ministry of reconciliation. What God has done through Christ, reconciling the world to himself, becomes something we imitate in our own lives, bringing divine reconciliation to the world.

What does this mean in practice? On the one hand, it means that we'll continually bear witness to what God has done in Christ. We'll tell the good news of reconciliation and invite others to be reconciled to God through Christ. Of course this is what we usually call evangelism. On the other hand, being an ambassador of reconciliation means that we'll demonstrate through our lives and through our fellowship the reality of the good news. We'll treat each other with the kindness God has shown to us. And we'll reach out with grace and mercy to those around us: healing the sick, binding up the brokenhearted, feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, and proclaiming the good news of God's kingdom to all the world. In other words, we’ll do those things that, in the end, Jesus the Son of Man receives as if they were done to him personally.

We don't care for people and seek to relieve human suffering with the expectation that we can somehow forge the kingdom of God by our own efforts. God alone can make all things new. But our compassion is an extension of the fact that we live as new people even now, that we experience, if only in part, the kingdom of God. Moreover, our compassionate care for hurting people is a reflection of the God who wipes away every tear. And it is motivated by the vision of God's future yet to come.

What I’ve just said explains why, throughout the centuries, Christians have been on the forefront of caring for the poor and seeking justice for the oppressed. For example, before the combination of earthquake and tsunami devastated Southeast Asia three weeks ago, World Vision – along with many other Christian agencies – was already at work in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, and many other countries. In May 2003 World Vision supplied water, food, blankets, and clothing to thousands of Sri Lankans who had lost their homes in deadly cyclones. This sort of tragedy barely made news in the United States, and, as far as I can recall, there wasn’t any widespread effort in our country to give aid to the people of Sri Lanka. But World Vision was there, not out of a temporary response to a terrible crisis, but out of a profound commitment to living in such a way that people can see the kingdom of God. The mission statement of World Vision says:

World Vision is an international partnership of Christians whose mission is: To follow our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ in working with the poor and oppressed to promote human transformation, seek justice and bear witness to the good news of the Kingdom of God.

Yet it isn’t enough for Christian people to sit back and let World Vision and other agencies do all of the heavy lifting. We are all called to live in such a way that we bear witness to the good news of the Kingdom. We can do this, to be sure, by supporting World Vision and similar organizations (Samaritan’s Purse, Bread for the World, The Salvation Army, etc.) But we must seek to live our lives each day so that the new creation shines through.

The Brokenness of Nature: A Sad Reminder

Appendix 1 to series: All Things New

Posted for Thursday, September 1, 2005

In January, in the aftermath of the tsunami in Southeast Asia, I wrote a short blog series in which I reflected theologically on nature and its capriciousness. In All Things New, I explained how God had created the world not only good, but very good. Yet in ways we don't fully understand, human sin led to the brokenness of God's excellent creation. Hence tsunamis. Hence hurricanes. Hence thousands of people killed and millions of lives turned upside down. I went on to show, however, that Christians hope for the eventual renewal of creation when God completes his saving work in this world. Yet, in the meanwhile, we life in the midst of a broken world that's in the process of being restored.

Now the sad reminder of the brokenness of creation has been brought much closer to home. Devastation covers the shores, not of some far away land with unfamiliar names, but of Louisiana and Mississippi. Many of us know people who have been hurt by the hurricane and its aftermath. All of us will be personally touched by this disaster, both in our hearts and in our wallets. And we'll know, once again, that the world is broken. As it says in the New Testament, "the whole creation has been groaning in labor pains until now" (Romans 8:22). We're caught up in this pain as we await the new creation yet to come.

Although pictures of flooded homes, destroyed apartments, piled up cars, and thousands of homeless people make me sad, I must admit that something else produces an even stronger visceral reaction within me, a powerful combination of anger and pain. I'm talking about looting. I'm sure you've heard the stories and seen the pictures. Throughout the devastated Gulf region people have been breaking into unguarded stores and helping themselves to all sorts of merchandise.

Of course in some cases people are stealing things they desperately need to stay alive: water, food, medicine. This sort of action is understandable. Moreover, I fully expect that we'll hear stories down the road of folks who have come back to the stores in order to pay for what they had taken. Good people do this sort of thing, and there are lots of good people in Louisiana and Mississippi. |

|

| |

|

The looting that elicits such a strong reaction is not about a desperate attempt to preserve life. It's an expression of greed and selfishness. It's taking advantage of a tragedy to enrich oneself with meaningless stuff. It's caring so much about oneself that one cannot stop to think about others.

Why do people loot in times of crisis? I'm sure we'll hear from the "experts" in the next few days, explaining looting as a result of poverty and social ostracism. It will end up being the fault of the government, or the businesses that were looted, or the whole society, for that matter. Of course the "experts" won't mention the fact that the vast majority of poor people along the Gulf didn't steal a thing. They'll miss the fact that looting has something to do, not only with the breakdown of community, but also the breakdown of a moral world in which there is recognized right and wrong.

I'm sure that looting can be explained from a number of perspectives. Yet I can't see how we can avoid the obvious. A person who loots is stealing. Putting aside cases of life and death desperation, the looter doesn't have the moral judgment to see that it's wrong. Or, if the looter has the moral judgment, then he or she lacks the moral will to refrain from obviously wrong behavior. Looting speaks of the failure of our society to help people become morally mature human beings.

| Yet this isn't the whole story either. The Bible has plenty to say about right and wrong, and it surely values moral instruction. But Scripture also teaches that human beings are evil on the inside, and are in need, not only of moral instruction, but of profound spiritual transformation. In an ironic passage in Genesis, after God destroyed most of humanity through a giant flood, He said, "I will never again curse the ground because of humankind, for the inclination of the human heart is evil from youth" (Genesis 8:21). Jesus said, "For it is from within, from the human heart, that evil intentions come: fornication, theft, . . ." (Mark 7:21). In other words, looters are simply living "from the heart," as it were. They're doing what comes naturally. This is no excuse, of course. But it is an explanation. |

|

| |

A looter having a free for all in a Wal-Mart in New Orleans. ( MSNBC)

|

Perhaps one of the reasons I'm so bugged by scenes of looting is that, at some level, I relate to the looters. They force me to confront things in human nature – indeed, in my own nature – that I'd rather deny. I can't imagine that I'd ever steal from a Wal-Mart, if, heaven forbid, the city of Irvine was devastated by some natural disaster, like an earthquake. But the greed and selfishness of my heart gets expressed in lots of other ways, ways that are much more subtle. Perhaps they're even more virulent because they're more easily rationalized away.

Let there be no doubt about it. Nature is broken, both the natural world and human nature. We human beings need, not only moral parameters to guide our behavior, but also spiritual transformation so that we might desire to do what's right.

And this is exactly what God provides, both through the revelation of Scripture, and through the work of the Holy Spirit in our hearts. Someday God will mend this broken world. This is our hope. But, in the meanwhile, if we open our hearts to God today, that healing process can begin in us right now. And then we can be agents of God's restoration in the world.

|