| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

Is the TNIV Good News? Volume 3 of 3

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2005 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com . Thank you.

Is It a Problem if the Bible Sounds "Different"?

Part 21 of the series “Is the TNIV Good News?”

Posted at 11:15 p.m. on Sunday, March 13, 2005

In my last post I referred to a curious experiment reported to me by one of my blog readers. As you may recall, this woman's high-school-aged daughter was in a Bible class at church. The vast majority of the members of her class were incensed that Zondervan was publishing an inclusive language Bible (some years ago). These high schoolers – from "today's generation," by the way – said they used and understood traditional language for people, in which words like "brothers" and "men" could refer generically to both sexes. A week later the mother, out of curiosity, tried an experiment in which she asked the "men" in the class to stand. Only the boys stood. Then she asked the students who their "brothers" were. They mentioned only their male siblings. In the conversation that ensued, the students agreed that in most of life they in fact used gender inclusive language and understood words like "men" to refer only to males. But when dealing with the Bible they had learned that different rules apply. Thus they were able to understand traditional interpretations and not to be put off by them because the Bible sounds different.

Commenting on this episode, I suggested that it could be used by both sides in the TNIV debate. Supporters would see this as proof that we need a gender inclusive translation. Opponents of the TNIV would use this case as evidence that a new translation is not needed, since the students clearly understood what the Bible intended even if it used language patterns that weren't their norm.

I want to reflect on this case a bit further, since I think it is typical. Millions of English-speaking Christians use gender inclusive language for the most part in their natural speech, but read Bible versions that employ traditional male forms of speech. My wife, for example, grew up using the NASB and the NIV translations. She says learned to reinterpret passages that referred to "brothers" and "men" inclusively – an extra layer of decoding, if you will – so she did not feel excluded by traditional translations.

Is it a good thing for people to use a Bible translation that diverges in significant ways from their own natural language patterns, whether we're talking about gender language or other expressions? More specifically, is the situation of the high school Bible class something we should encourage? Or is it a problem in need of correction? |

|

| |

A portion of an early third-century papyrus (p46) of Paul's letters to the Galatians and the Philippians.

|

The clear advantage in this situation is that the students would be able to use word-for-word translations without misunderstanding the intent of the traditional male language. They'd know that when the text said, "If a brother sins" it actually includes either male or female Christian siblings. Thus these students would be able to use translations that are formally closer to the original languages of the Bible and in this sense less interpretive.

It seems to me that there are numerous problems with using a Bible translation with gender language that is out of sync with normal language patterns. As I've said before, I'm not suggesting that all speakers of contemporary English use gender inclusive language. Many do not. But the example I'd dealing with now in fact concerns people who ordinarily use inclusive language but whose biblical version in not inclusive. This, I fear, can lead to several problems. I'll discuss one of them today.

1. The first downside of using a Bible translation that does not reflect normal speech patterns of a community is the possibility of a genuine misunderstanding of the text.

People may think that they can take the traditional gender language of word-for-word translations and grasp the inclusive sense of a passage, and in many cases I expect this is true. But there is also a real danger, it seems to me, of people reading into a text what is not there in the original. One might read a verse that refers to "man" generically, meaning "man as male and female," and nevertheless believe that this verse somehow refers to "man as male" more than "man as female."

A related problem is the inadequacy of traditional English language for man. The English word "man" can mean "a male person" or "a human being." Greek, on the other hand, has two (at least) different words that are traditionally translated as "man" in English. One, anthropos, is usually used in reference to a human being (regardless of gender), while the other, aner, is usually used in reference to a male adult. (I have to qualify these usages because there are many variations.) This means that when you read the word "man" in the NIV, for example, you often can't be sure which Greek word it translates. Thus when you come upon Romans 3:28 in the NIV, you find, "For we maintain that a man [anthropon, accusative case of anthropos] is justified by faith apart from observing the law." Context suggests the generic meaning of "man" as human being, of course. But from the English you can't really know for sure. The TNIV of this verse reads, "For we maintain that a person is justified by faith apart from observing the law." In this case, therefore, the TNIV is clearer than the NIV because it isn't stuck only with the traditional "man." Those who argue that the traditional male language is more accurate often forget the lack of clarity inherent in the English word "man." In many cases the traditional language is actually less accurate and more open to misunderstanding than inclusive language translations because "man" can stand in for anthropos or aner.

The NIV, I might add, is notorious for including the word "man" when neither anthropos nor aner is present in the Greek, thus shading the translation in a masculine-sounding direction. Take Matthew 11:6, for example. The Greek reads quite literally, "And blessed is whoever is not scandalized by me." The NIV translates this as "Blessed is the man who does not fall away on account of me." A case of adding the word "man" to Scripture?? Nah! Just a bad translation from the perspective of today's English. The TNIV improves upon the NIV by translating, "Blessed is anyone who does not stumble on account of me." Interestingly enough, the ESV sides with the TNIV in this case by translating inclusively, "And blessed is the one who is not offended by me." Although I don't know this for a fact, my guess is that this sort of problem in the NIV is one of the reasons that the key leaders of the anti-TNIV movement were the main translators of the ESV. Like the TNIV translators, though operating with different priorities, they sensed the inadequacy of the NIV for "today's" readers.

Tomorrow I'll lay out a second downside of using a Bible translation that does not reflect normal speech patterns.

Is It a Problem if the Bible Sounds "Different"? (Section B)

Part 22 of the series “Is the TNIV Good News?”

Posted at 11:55 p.m. on Monday, March 14, 2005

Yesterday I began to answer the question: "Is it a problem if the Bible sounds 'different'?" This question arose from a specific situation in which a group of Christian high school students discovered that, though they used inclusive language in most of life, they had learned that the Bible sounds "different." In common speech these students would not understand "men" as a reference to both males and females. But, when they read their Bibles, they understood that different rules applied.

After spelling out the positive implications of this situation, I began yesterday to consider the downside. Here was point one:

1. The first downside of using a Bible translation that does not reflect normal speech patterns is the possibility of a genuine misunderstanding of the text.

Today I move to the next point.

2. The second downside of using a Bible translation that does not reflect normal speech patterns is the tendency for the Scripture to sound odd, unnatural, or old-fashioned.

The high school students in my example had learned to accept the fact that the Bible used language in a way different from their normal speech. They accepted the oddness of the biblical language without complaint. But I'm not at all sure this is a good thing, even though it meant that these students didn't misunderstand the basic meaning of a traditional Bible translation.

Should a translation sound odd, unnatural, or old-fashioned? Yes, if there's a good reason for this. Sometimes, for example, writers intend for their writing to odd, even dated. Many commentators have argued that Luke, in the first chapter of his gospel, actually imitates the style of the Greek Old Testament. He wants his text to sound, well, biblical. It would be rather like if I tried to write in the style of the King James Bible. If the commentators have correctly identified Luke's stylistic agenda, then it would be right for a biblical translator to capture Luke's intended anachronism in an English translation. Luke 1 should, in fact, sound a bit "thus saith the Lord-ish".

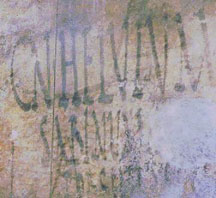

But I would argue that, for the most part, a translation of one text into another language should attempt not only to render the meaning of the source text into the receptor text, but also to convey the "feel" of the text. So if you're translating a proclamation by a Roman emperor, then you should try to make it sound imperial. If you're translating an informal letter, then you should strive for a more casual sound. And if you're translating graffiti from the walls of Pompeii, then you could even use slang, maybe even crude language in some cases.

For the most part, the writings of the New Testament were not formal. They weren't street slang either. But their speech, by and large, was the ordinary language of ordinary people. Thus the best translation of the New Testament text into English would use the ordinary language of ordinary people. And if it turned out that English speakers had a wide range of ordinary usage, then we might well need more than one translation. A translation that sounded odd, unnatural, or old-fashioned would be less accurate than one that rendered the original language into the natural forms of the speakers for whom the translation was intended. This means, therefore, that even though those high school students could understand their traditional translation, it wasn't necessarily the best translation for them because it didn't convey the directness and ordinariness of the biblical language. |

|

| |

This is a bit of graffiti from the walls of Pompeii, upon which are found hundreds of graffiti. Much of the graffiti is political, including the example above which supports the political candidacy of Gnaeus Helvius Sabinus. A lot of the graffiti at Pompeii is sexual in theme, though crude. If you read scholarly translations of graffiti from Pompeii, you'll find many R-rated profanities. |

Let me illustrate my point with a fairly non-controversial matter of biblical translation. Classic translations (KJV, RSV, etc.) rendered the Greek attention-getting word idou as "behold," for example: "Behold, I stand at the door, and knock" (Rev 3:20). No doubt there was a time when English speakers normally used the word "behold" to get people's attention. But that time is no more, at least in ordinary speech. So when it comes to idou in Revelation 3:20, most recent translations use some other word or phrase: "Here I am!" (NIV, TNIV); "Look!" (NLT); "Listen!" (NRSV, NET, CEV, HCSB). Among recent translations of which I am aware, only the ESV stays with the classic "Behold." But this, I would argue, is not even a good word-for-word translation, unless one lives in a community of English-speakers who still use the word "behold" to get people's attention (the Amish in Pennsylvania, perhaps?). The fact that the ESV uses "behold" over a 1000 times (both for the Greek idou and for the Hebrew hinneh) gives it an old-fashioned sound which, I would argue, should not be there, except in odd texts like Luke 1. "Behold," even though traditional, is less accurate than other options.

Let me conclude with a pastoral observation. One of the greatest challenges I face as a pastor is helping people, both church members and visitors, both Christians and non-Christians, grasp (or, better, be grasped by) God's Word. Now I realize that this work is ultimately not mine, but it belongs to the Holy Spirit. Nevertheless, as a preacher and teacher I try to help folks connect with Scripture. Part of what makes this hard is that the Bible was written in a different time and culture. People today naturally feel a distance between themselves and the Bible. I resist many of the ways people try to "update" the Bible to make it "palatable" to a contemporary audience because so many of these ways diminish its message and blunt its sharpness. But, though I'll always love the poetic sound of the King James Version, I would rarely use this translation because it would create one more kind of distance between God's written Word and the people who so desperately need to read it and understand it. Even as the biblical writers used the language of common people so they might "get it," I want to do the same. Thus, even if someone could understand an old-fashioned translation, I would resist recommending this translation unless I had a very good reason for doing so.

Sometimes a good reason exists. Recently a member of my church asked for a recommendation for a theologically-sophisticated study Bible. Knowing this man and his situation, I enthusiastically recommended The Reformation Study Bible in the English Standard Version. Yes, this is the version I just criticized for using "behold" over 1000 times. But, as I've said before, every translation involves hundreds of thousands of decisions and nobody will like all of them. For this man and the sort of study he wants to do, I'm quite sure he'll do fine with the ESV, "beholds" and all. Nevertheless, I believe that, in general, a biblical translation should strive to capture both the meaning and the "feel" of the original text to the extent this is possible. Even if people can figure out what a translation means, the more unnatural it sounds the less helpful it will be. After all, a reader of the Bible in translation shouldn't have to decode the English translation to get at the original sense of the Greek.

I do realize, though, that some pastors and Christian leaders are willing to put up with the old-fashioned sound of their preferred translation for various reasons, often because they believe it to be an especially accurate translation. I respect this decision, in part because I think it usually reflects the dynamics of a church and community that can only be understood by a mature leader in that church and community. But I think it is important for those who choose a translation that might be somewhat out of date to realize the downside of their decision. I've said before that every translation has strengths and weaknesses. None is perfect. Yet if we recognize the weaknesses and imperfections of the translation we use, we'll be better able to work around them rather than being limited by them.

In tomorrow's post I want to discuss one further dimension of the "out of sync" translation problem.

Is It a Problem if the Bible Sounds "Different"? (Section C)

Part 23 of the series “Is the TNIV Good News?”

Posted at 11:15 p.m. on Tuesday, March 15, 2005

Receiving the Gauntlet . . .

Oh-oh! Today Hugh Hewitt threw down the gauntlet in my direction, asking if I have "deconstructed the TIME cover story on the Protestant Mary." My answer: "No, because I don't get my copy of TIME until tomorrow." But, having scanned the article online, I do want to go after it. I'll do so starting tomorrow. This means I'm going to take a break in my TNIV series for several days. This also explains why today's post is even longer than usual. Tomorrow I'll get to the Protestant Mary. |

|

|

|

|

It's hard to resist the power of the gauntlet of Hugh Hewitt. Hmmm. I wonder why. . . .

|

I've been mulling over the question: "Is it a problem if the Bible sounds 'different'?" As you know if you've been reading my blog during the last few days, this question arose from a situation in which a group of Christian high school students discovered that, though they used inclusive language in most of life, they were comfortable with a traditional, non-inclusive translation because they had learned that the Bible sounds "different." Though in their everyday speech "men" and "brothers" referred only to males, when they read the Bible they understood these words inclusively.

Although there are some advantages in this situation, I think there are several disadvantages as well. So far I've outlined two:

1. The first downside of using a Bible translation that does not reflect normal speech patterns is the possibility of a genuine misunderstanding of the text.

2. The second downside of using a Bible translation that does not reflect normal speech patterns is the tendency for the Scripture to sound odd, unnatural, or old-fashioned.

Today I want to address one additional problem.

3. The third downside of using a Bible translation that does not reflect normal speech patterns is the tendency for such a translation to miscommunicate with and exclude people who are outside the Christian community.

(Note: If you're just joining this conversation, when I refer to "normal speech patterns" I mean "normal speech patterns of a particular group at a particular time." I'm not assuming that gender inclusive language is the norm for the English-speaking world. In fact I've argued that there is a broad diversity of usage when it comes to this sort of language.)

In the example upon which I've based this discussion the students who used inclusive language in ordinary speech, but non-inclusive language when it came to the Bible, had no problem with their traditional translation. This was because they were familiar and comfortable with the disjunction between their common language and the language of their Bible translation, and because they were part of a Christian community that regularly read and studied this traditional translation.

But I wonder what would happen if one of these students invited a non-Christian friend to church. Would this friend be as familiar and comfortable with non-inclusive language? I rather doubt it. And if this friend happened to be female, would she hear the Bible as speaking directly to her? She could probably decode the traditional language so that she could grasp its personal impact, though in some cases I'd expect that she might not do so. But even if she did, I worry about the artificial barrier that would be erected between this young woman's reading of the Bible and her own soul. Therefore, if Christians use a traditional translation in a community where inclusive gender language is common, they run a great risk of being misunderstood by people outside of the church, or even excluding some of these people from hearing the good news.

Consider this hypothetical example. Suppose the high school pastor of the church with the high school Bible class read the NIV translation of John 15:5b: "If a man remains in me and I in him, he will bear much fruit." (The Greek translates literally, "The one remaining in me and I in that one/him, this one/he bears much fruit.") Presumably most if not all of the Christian members of the group would understand this verse inclusively. But it seems quite possible that a visitor might not get the inclusive sense of this promise, believing instead that it was addressing males and not females. Of course it could be explained that Jesus was speaking inclusively, and I expect the pastor would do this. But the possibility of a serious misunderstanding concerns me. Moreover, what if a female visitor happened to pick up an NIV Bible in order to read it for herself? How would she respond to the gap between the biblical language and her common speech? Would she believe that, as a female, she was somehow excluded? Would it seem to her that, even if she could make sense of the text, women were somehow second-class citizens in God's kingdom? Wouldn't it be better if the Bible she read used the patterns of speech with which she was familiar?

As I've read pages upon pages of criticism of the TNIV, it seems to me that the critics often think almost exclusively of reading the Bible in a relatively closed Christian community, one in which we can teach the "right understanding" of gender language so that people won't misunderstand the text. But don't we want the Bible to be readily understood by people outside of the church, even those who live in communities where inclusive language is the norm? Do we want to risk the possible misunderstandings that will come if our translation is substantially out of sync with the language of the secular culture around us?

I expect that the TNIV critics would answer that this risk is quite small, and that there is a greater risk of misunderstanding the true meaning of God's Word if a Bible uses inclusive language. This may well be true in the communities in which the TNIV critics live and move and have their being. But those of us who live in places where inclusive gender language is the norm cannot agree that the risk of misunderstanding is insignificant. On the contrary, the risk of misunderstanding and exclusion is genuine and serious. I know this because I live in such a community and I've wrestled with this issue for many years. To be sure, there are many people in my city who are familiar and comfortable with non-inclusive language. But there are many others as well who are not so familiar and comfortable, and, for whatever reason, my church seems to be a place where many of these folks come looking for God.

As a preacher, I want to challenge non-believers with the timeless truth of God's Word. I want to scandalize them, if you will, with the extraordinary center of the gospel, which is Christ crucified. I want them to encounter this stumbling block as they consider God's call upon their lives. But I don't want my Bible translation to pose an unnecessary stumbling block. I don't want women and men from secular contexts to miss the point because my language or my Bible translation sounds peculiar. Nor do I want to convey that I am cut off from their world to such an extent that I don't share their language patterns. Nor do I want them to think the Bible is "old-fashioned" just because my translation uses unfamiliar and, to them, outdated language patterns.

Now I realize that some TNIV critics just don't buy the fact that inclusive language is as common as I seem to assume. They'll roll out examples from secular magazines and newspapers to prove their point. I fully agree that there is a great deal of variation in the use of inclusive language even in our secular culture today. But I know the way language functions in significant segments of the world in which I live, and I know that many of my neighbors use and expect the use of gender inclusive language. For most of these people, there's no social agenda associated with this expectation. It's simply the way they speak English.

From my perspective, one of the great and sad ironies of the TNIV debate is that the opponents of the translation seem, on the one hand, rightly concerned to preserve the relevance of Scripture to the individual, and on the other hand, so unaware of how a traditional translation can in fact obscure this relevance for many readers. You may recall the criticism of the TNIV translation of Revelation 3:20 in the "Statement of Concern" (which I addressed in posts beginning with Part 10). This criticism included the following line: "In hundreds of such changes [singular to plural], the TNIV obscures any possible significance the inspired singular may have, such as individual responsibility or an individual relationship with Christ." But what the TNIV critics don't seem to understand is that when the singular in an English translation is a male noun or pronoun, this also can obscure the significance of the text for an individual relationship with Christ, if that individual happens to be a female. (The problem isn't in the masculine Greek word, by the way. Nobody I know of is criticizing the words God inspired two millennia ago. Insinuations to the contrary obscure the truth and ought to be avoided.) Rather, the problem for us is getting the authentic meaning of that inspired masculine Greek word into an English translation that makes sense for today's readers, especially female readers, if they happen to use and to expect gender inclusive language. I fully agree that not all of "today's readers" fit into this category. But many do.

At the very beginning of this series I talked about my own translation choices. Over the past several years I've used a variety of translations, some gender inclusive (NRSV, NLT) and some not (NIV, NKJV, NASB). When I have chosen to use a gender inclusive translation – fully aware of the potential problems inherent in such a translation, by the way – I have done so precisely because I want all people who hear my preaching or teaching to wrestle with their "individual responsibility or an individual relationship with Christ." In particular, I don't want a woman or girl who is unfamiliar with traditional masculine language to miss the fact that God's Word addresses her directly and personally. I don't want her to have to decode the text for herself in order to grasp its meaning. Sure, it would make things much easier of the language rules of twenty-seven years ago still applied (that's when the NIV was fully released). But, at least where I live and for many of the people with whom I live, these rules have been replaced by something new. So, my calling as a preacher and teacher is to find a way to convey God's Word clearly and accurately to the people to whom I have been called. If this means I need to use an inclusive language version of the Bible in some contexts, so be it.

But at this point some of my readers are no doubt thinking: "Come on, Mark. Get a hold of yourself! Isn't this whole inclusive language thing just a matter of selling out to political correctness? And isn't the whole shift in language that you keep talking about a result of an anti-Christian feminist agenda? Wouldn't you be better off as a preacher and teacher if you opposed such social pressures and stuck with a clear, simple, traditional translation of the Bible?"

These are important questions, and I will get to them when I return to this series in a few days. Besides, maybe after a few days of a breather I'll have an easier time getting a hold of myself.

|