|

N.Theology of Work; Theology of Work Project; Theology of Work in Ezra and Nehemiah

A Theology of Work in Ezra & Nehemiah

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2009 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com. Thank you.

Introduction: Reading with an Agenda

Part 1 of series: A Theology of Work in Ezra and Nehemiah

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

Yesterday I introduced a project to which I will soon be contributing, the Theology of Work Project (TOWP). This effort includes a systematic reading of the whole Bible, looking in every book for its theology of work. In time, the findings from this particular investigation will be published as a kind of biblical commentary. I have seen some early drafts of some of the material, and it is excellent. The more I learn about this project, the more enthusiastic I become.

My particular assignment, as I explained yesterday, is to focus on the Old Testament books of Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther. This might seem like a surprising allocation, given that my academic expertise is in New Testament. But, as you may know, several years ago I wrote a commentary on Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther. So, though I’m not an Old Testament scholar, I do have a measure of expertise in these particular books.

Ultimately, I will produce a focused, commentary-like study of Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther, one that seeks to answer the question: What is this book’s theology of work? I will not be publishing that production here, because it will be part of TWOP’s “library.” But I do want to work through my assigned biblical texts as a part of my blog. Not only will this give my readers a chance to think about these issues with me . . . a worthy effort, I believe. But also, I will have the chance to learn from my readers through their posted comments and emails.

But before I get to the task at hand, I want to say something about reading with an agenda.

We always approach a reading assignment with some sort of purpose or plan. When I’m on summer vacation, for example, my agenda is enjoyment. When I’m reading a book for work, usually I’m trying to glean material that will be relevant for the mission of Laity Lodge. When it comes to most reading, we want to let the text speak for itself, to tell its story or explain its point.

When I was writing my commentary on Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther, my goal was to let these books speak in their own voice. Beyond this, I was hoping to accurately hear the voice of God. I tried not to bring to the text my own questions that we’re extrinsic to the text itself. In particular, I was not asking Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther to offer a theology of work, since this was not the main point of these writings. Rather, I sought to let Ezra and Nehemiah speak about restoration and renewal, the primary themes of these books. And I tried to let Esther speak about living in a culture in which one doesn’t fit, a central them of this book.

Now, however, I am bringing to Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther a question that is not the primary question of these books. Yet I am still hoping to hear what they say in some authentic way, and not merely interject my own ideas into the text. In many cases I will be listening to what is implicit in the telling of the story. In other cases I will be dealing with what is explicit, even if it isn’t the main point.

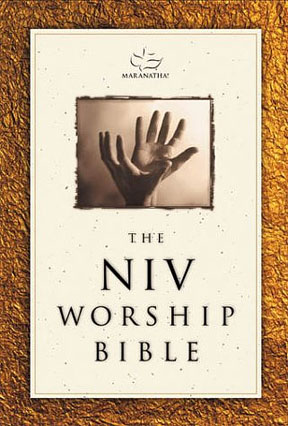

I believe that this kind of reading, when it is done with careful attention to the primary meaning(s) of a text, can be quite illuminating. I experienced such illumination a decade ago when working on the NIV Worship Bible. For this Bible, which is now out of print, I was invited to write the introductions to all of the biblical books. These introductions were not your standard study Bible fare, however, with brief notes about authorship, date, context, outline, and themes. Rather, my introductions sought to answer the question: What does this book teach us about worship? I believe that this kind of reading, when it is done with careful attention to the primary meaning(s) of a text, can be quite illuminating. I experienced such illumination a decade ago when working on the NIV Worship Bible. For this Bible, which is now out of print, I was invited to write the introductions to all of the biblical books. These introductions were not your standard study Bible fare, however, with brief notes about authorship, date, context, outline, and themes. Rather, my introductions sought to answer the question: What does this book teach us about worship?

In order to answer this question for each biblical book, I had to read the book at least twice. As I read, I kept asking myself questions like: What does this have to do with worship? What view of worship is assumed here? And so on. In the process of writing the introductions, I learned a lot about worship. And I’m quite sure I didn’t just project my own thoughts into the text, because much of what I learned I hadn’t thought before I began my study.

So, as I get ready to look for theological material related to work in Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther, I am bringing my agenda, if you will. This agenda is not, however, something I want to force into the text. Rather, my agenda is to ask, as openly as I can: What does this book teach us about work?

An Introduction to Ezra

Part 2 of series: A Theology of Work in Ezra and Nehemiah

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

The Old Testament book of Ezra was originally the first part of one continuous work that included the book we call Nehemiah as the second part. The story of Ezra-Nehemiah was written as a continuous narrative.

We don’t know much about the writer of Ezra-Nehemiah, other than what we can glean from the books themselves. It’s evident that the writer, who was either the same person or someone closely related to the person who wrote 1 and 2 Chronicles, used a number of primary sources in telling the story of the rebuilding of Jerusalem and its Temple after the Babylonian exile. The date of writing must have been later than 430 B.C., when the action of Nehemiah concludes, and probably occurred before 300 B.C.

The theme of restoration pervades Ezra-Nehemiah. In my commentary I utilized the following basic outline for these books:

1. Restoration of the Temple (Ezra 1:1-6:22)

2. Restoration of Covenant Life, Phase One: The Work of Ezra (Ezra 7:1-10:44)

3. Restoration of the Wall through Nehemiah (Neh 1:1-6:19)

4. Restoration of Covenant Life, Phase Two: Ezra and Nehemiah Work Together (New 7:1-13:31)

Notice that Ezra himself does not appear in the book the bears his name until the last four of its ten chapters.

The two-volume work of Ezra-Nehemiah make sense in light of the covenant between God and Israel forged at Mt. Sinai. There, God entered into a covenant relationship with Israel, promising to bless the nation if the people would only be faithful to God by obeying his law. Unfaithfulness would lead to divine judgment. Unfortunately, the Israelites persistently rebelled against God, rejecting his law and pursuing other gods. Thus God’s judgment fell upon his people, with the final blow delivered in 587 B.C. by the Babylonians under the leadership of King Nebuchadnezzar. They killed the leaders of Judah, burned the temple in Jerusalem to the ground, and took the finest of Jerusalem’s citizens back to Babylon. Thus began the Exile.

The book of Ezra begins to tell the story of restoration after the Exile, as the Israelites are returned to Jerusalem in order to rebuild their Temple as well as their life as a covenant community. Here’s how the narrative begins:

1 In the first year of Cyrus king of Persia, in order to fulfill the word of the LORD spoken by Jeremiah, the LORD moved the heart of Cyrus king of Persia to make a proclamation throughout his realm and to put it in writing: 2 “This is what Cyrus king of Persia says: “‘The LORD, the God of heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth and he has appointed me to build a temple for him at Jerusalem in Judah. 3 Anyone of his people among you — may his God be with him, and let him go up to Jerusalem in Judah and build the temple of the LORD, the God of Israel, the God who is in Jerusalem. 4 And the people of any place where survivors may now be living are to provide him with silver and gold, with goods and livestock, and with freewill offerings for the temple of God in Jerusalem.’” (Ezra 1:1-4, NIV)

After Cyrus overthrew Babylon in 539 B.C., he authorized the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem. His action fulfilled the prophecy of Jeremiah concerning the length of the Exile. But the prophet Isaiah had been even clearer about the divinely appointed role of Cyrus himself:

1 “This is what the LORD says to his anointed, to Cyrus, whose right hand I take hold of to subdue nations before him and to strip kings of their armor, to open doors before him so that gates will not be shut. . . . 4 For the sake of Jacob my servant, of Israel my chosen, I summon you by name and bestow on you a title of honor, though you do not acknowledge me. . . . 13 I will raise up Cyrus in my righteousness: I will make all his ways straight. He will rebuild my city and set my exiles free, but not for a price or reward, says the LORD Almighty.” (Isa 45:1, 4, 13)

This is the story told in the first chapters of Ezra. To those chapters I’ll turn in my next post as I consider the theology of work in Ezra.

A Theology of Work in Ezra?

Part 3 of series: A Theology of Work in Ezra and Nehemiah

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

If you’re just now joining this series, let me say that I’m doing some blogging on a theology of work in the biblical books of Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther. This exercise is my first step toward producing a short “commentary” on these books for the Theology of Work Project. (If you missed my explanation of TOWP, you may want to check this post.) I’m looking first at the book of Ezra, then at Nehemiah and Esther, with this question: What does this book teach us about a theology of work? Or, to put it differently: What do we learn from this book about how work relates to God and vice versa?

If you’re is looking for a biblical theology of work, you shouldn’t start with Ezra. Frankly, there is little in this book that speaks directly about work and its relationship to God. Partly this has to do with the genre of Ezra. It is a narrative, an historical narrative that describes, from a theological perspective, what happened in a key time of Israel’s history. The narrative contains nothing in the way of legal texts or prophetic pronouncements, no didactic material of any kind. You won’t find theological ruminations on work in Ezra.

You do find people working, however, and this might provide some grist for the TOWP mill. Primarily, Ezra includes two kinds of work. The first is the “work” of Israel’s sacrificial worship. Other than the giving of gifts for the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem and travel from Babylon to Jerusalem, the first real work in Ezra is the building of an altar to God, on which sacrifices were then offered to God (Ezra 3:1-6). Prior to this building, a long list of names includes the professions of those who labor in some aspect of the Temple’s activity: priests, Levites, singers, gatekeepers, and temple servants (Ezra 2, esp. 2:70).

The second kind of work in Ezra is closely related to the first. It involves building, most of all, building (or rebuilding) the Temple in Jerusalem. The first six chapters of Ezra focus on this activity. In fact, the Hebrew verb “to build” (bnh) and its Aramaic cousin (for part of Ezra is written in Aramaic), appear 31 times in Ezra (in the first six chapters, to be exact). No book of the Old Testament utilizes the verb “to build” more frequently than Ezra. It is a book about building. And building is work, hard work.

I don’t what to read between the lines here too creatively, as if Ezra contains some arcane theology of work that can be decoded if we only have the secret decoder ring. This book mainly underscores what is plain elsewhere from Scripture, truths such as: Work is an ordinary part of ordinary life. Work is something for which God has given us the ability. Work can be hard. Work takes organization. Work matters to God. Yet it would be stretching things to say that Ezra teaches these truths. They are more like background assumptions, part of Ezra's theological worldview.

Ezra does offer a theologically engaging account of the relationship between human work and God’s help. We find this especially in Ezra 5. In context, the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem came to a standstill because of opposition to this effort from various opponents (4:24). But God, speaking through his prophets Haggai and Zechariah, helped to get the project going again (5:1-2). Nothing could derail it this time. Thus the temple-building part of Ezra ends with good news:

So the elders of the Jews continued to build and prosper under the preaching of Haggai the prophet and Zechariah, a descendant of Iddo. They finished building the temple according to the command of the God of Israel and the decrees of Cyrus, Darius and Artaxerxes, kings of Persia. (6:14)

What enabled the Temple to be rebuilt following the Exile? To be sure, it took plenty of hard work by the leaders of the Jews and by the expert craftsmen whom they paid to help (3:7). And, of course, it would not have happened apart from the initial decree of Cyrus and the continued support of the Persian rulers. But God’s hand empowered and guided the rebuilding effort, both in raising up Cyrus to do his bidding and in emboldening the leaders of the Jews through the prophecies of Haggai and Zechariah.

The book of Ezra, therefore, underscores the value of human labor and leadership. But it also reminds us that, apart from God’s superintendence, human work is ultimately in vain.

Introduction to Nehemiah

Part 4 of series: A Theology of Work in Ezra and Nehemiah

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

Last week I introduced the Theology of Work Project (TOWP). I explained the vision of this project and my own participation in it. My task, as you may recall, is to do a commentary-like overview of the Old Testament books of Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther. For each book, this overview seeks to answer the question: What is the theology of work in this book?

As I mentioned before, none of these books is composed primarily of didactic or legal or prophetic material. You can’t turn to a chapter that instructs on the nature of work or how we should do it. Rather, Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther are narratives, and in these narrative, work happens. Thus we can learn from the example of the “workers” in these books. Moreover, upon occasion, one of the leading characters says something that, by implication, helps us to glimpse an implicit theology of work.

At the end of last week I examined the book of Ezra, introducing the text and then examining it for theology of work material. Ezra doesn’t have much to say about work, per se, though it does feature a kind of work, namely building (or rebuilding) the Temple in Jerusalem. This effort reveals something of the nature of work, when seen from a biblical point of view.

The book of Nehemiah is similar to Ezra in many ways. This comes as no surprise, of course, once we know that Ezra and Nehemiah were once part of a single, two-part work. In fact, in my commentary on Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther for the Communicator’s/Preacher’s Commentary series, I treated Ezra-Nehemiah as a single work. The book we call Nehemiah continues the story began in Ezra, focusing on the rebuilding of the wall of Jerusalem and the rebuilding of the people of God in light of the covenant.

The book of Nehemiah, which features the rebuilding efforts of the man Nehemiah, opens by placing the events in a historical context: “In the month of Kislev in the twentieth year, while I was in the citadel of Susa . . .” (1:1). This gives us a date and a place. Of course we have to ask, “In the twentieth year of what?” The answer comes in Neh 2:1, where it says, “In the month of Nisan in the twentieth year of King Artaxerxes . . .” (2:1). But even this isn’t entirely helpful, because the Persians had three kings named Artaxerxes. So which one is in view here? Though there is not scholarly unanimity on this matter, many believe that Nehemiah refers to Artaxerxes I who ruled from 465 to 423 B.C. This would place the beginning of Nehemiah in 445 B.C., which would be about thirteen years after Ezra’s work in Jerusalem.

The “citadel of Susa,” or perhaps the “capital of Susa,” points to the winter lodging for Persian kings. The city of Susa, located in modern Iran, not far from the Iraqi border, included a large palace that had been built by Darius. The fact that Nehemiah was in Susa suggests what is made explicit in the last verse of the first chapter, that Nehemiah was associated with the Persian king Artaxerxes I. (Photo: Excavation of the palace in Susa. The cell phone tower in the background was a later addition, not found in the time of the Persian kings.) The “citadel of Susa,” or perhaps the “capital of Susa,” points to the winter lodging for Persian kings. The city of Susa, located in modern Iran, not far from the Iraqi border, included a large palace that had been built by Darius. The fact that Nehemiah was in Susa suggests what is made explicit in the last verse of the first chapter, that Nehemiah was associated with the Persian king Artaxerxes I. (Photo: Excavation of the palace in Susa. The cell phone tower in the background was a later addition, not found in the time of the Persian kings.)

In fact, Nehemiah was the king’s “cupbearer” (1:11). To us, this may sound like a lowly position. After all, Nehemiah was not only the one who held the king’s cup, but also the one who tested the king’s drink to make sure it was safe. Even as Secret Service agents are committed to “take a bullet” for the President, so Nehemiah was willing to “drink the poison” to protect his king. But, in reality, the cupbearer was also a trusted adviser to the king. He enjoyed a position of honor, luxury, and authority. As we’ll see in the unfolding drama of Nehemiah, his position with the king was crucial in his effort to restore the city of Jerusalem.

In my next post I’ll have more to say about what we learn about Nehemiah in chapter 1, and how this touches upon our understanding of work.

Work and Prayer in Nehemiah 1

Part 5 of series: A Theology of Work in Ezra and Nehemiah

Permalink for this post / Permalink for this series

In the Old Testament book of Nehemiah, chapter 1 introduces the main character and sets up the story of the book. Nehemiah is a Jewish man who worked as the cupbearer for the Persian king Artaxerxes. While serving the king in his winter residence at Susa, Nehemiah received a report about the state of his fellow Jews who had returned to Jerusalem from their captivity in Babylon. The report was dire, focusing especially on the vulnerability of the city because its walls had been destroyed.

In response to this intelligence, Nehemiah “sat down and wept.” Then, for says he “mourned, fasted, and prayed to the God of heaven” (1:4). In this prayer Nehemiah confessed God’s covenant faithfulness and the covenant unfaithfulness of the Jews. He asked for God’s help with his plan, yet unexplained, that would require the support of the king (1:11).

Nehemiah 1 introduces his work as cupbearer in the final verse. Thus the chapter leaves to the reader to fill in the blanks concerning this assignment. As I explained in yesterday’s post, the cupbearer was a committed servant to the king and often a trusted adviser. Nehemiah’s work was in support of a pagan king, and would have required full commitment as well as countless hours of service.

Nehemiah 1 also presents Nehemiah as a person of faith, a man of prayer. In fact, his passion for the people of God is powerful enough to lead Nehemiah to risk his life and radically change his career path.

The introduction of Nehemiah illustrates how work and prayer can be joined in our lives. Surely, Nehemiah became the king’s cupbearer because of his excellence in royal service. Yet this consummate professional was also a man of deep religious conviction. We do not see in Nehemiah a tension between secular employment and devotion to God. Rather, they appear to go hand-in-hand. (Photo: A sign outside of the Benedictine Monastery in Rudy, Poland.) The introduction of Nehemiah illustrates how work and prayer can be joined in our lives. Surely, Nehemiah became the king’s cupbearer because of his excellence in royal service. Yet this consummate professional was also a man of deep religious conviction. We do not see in Nehemiah a tension between secular employment and devotion to God. Rather, they appear to go hand-in-hand. (Photo: A sign outside of the Benedictine Monastery in Rudy, Poland.)

Nehemiah 1 presents the man Nehemiah as a potential poster child for the Benedictine Order, the motto of which is ora et labora (“prayer and work” in Latin. This, by the way, was apparently not stated by St. Benedict himself, but rather reflects a 19th condensation of Benedict’s emphases.) Nehemiah works and Nehemiah prays. Both are expressions of his covenantal relationship with God. Both are ways Nehemiah lives out his faith. Both will be used by God in his effort to bring restoration to the Jewish people.

|