| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

The Nativity Story and the Real Mary

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2006 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com . Thank you.

The Nativity is Coming!

Posted for October 17, 2006

One of my biggest pet peeves is the tendency for stores to rush into Christmas season before Thanksgiving. Of course, these days, Christmas marketing often begins before Halloween! Ugh!

You might think I'm being a bit of a hypocrite with this blog post, since it has to do with Christmas, and since we're still in the middle of October. But at least let me explain what I'm doing and why.

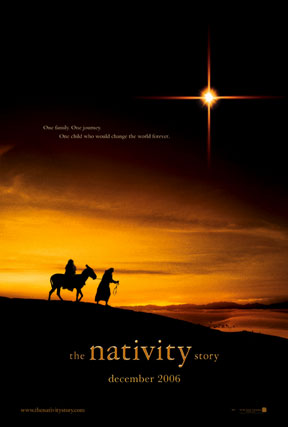

This December brings an outstanding ministry opportunity. I'm speaking of the release of the film called The Nativity Story. (See also the official movie website, which has a fancy and rather slow Flash intro.) The film will be in theatres on December 1, 2006. What is this film about? Simply stated, it tells the story of the birth of Jesus.

When I first heard about The Nativity Story, I felt nervous. Would this be a "debunking" sort of film, one that promises to tell "the real story" about the birth of Jesus, a film that strips the miraculous out of the gospel narratives? I can now say with confidence that this is not the case, since I've been able to check out the script. In fact, The Nativity Story retells the story of the birth of Jesus in an imaginative but basically traditional way. (Some will object that it is too traditional, no doubt.)

I expect that this film will raise popular interest in the birth of Jesus, and especially in Mary, who is played by Keisha Castle-Hughes (of Whale Rider fame). This means that we Christians need to be prepared to talk intelligently about the Christmas story in general and about Mary in particular.

Scot McKnight, one of my favorite biblical scholars and an outstanding blogger to boot, has written a book that comes just at the right time: The Real Mary: Why Evangelical Christians Can Embrace the Mother of Jesus. It will be released by Paraclete Press in early November (prior to the official publication date you'll find at Amazon).

I have had a chance to look at an advanced copy of The Real Mary. It contains just what I'd expect from a popular book by Scot McKnight: rock-solid biblical scholarship communicated in a style that is suitable for all readers. This book will be extremely helpful while there is widespread interest in The Nativity Story. But it will have enduring value as a trustworthy guide for evangelical Christians who wonder what to think about Mary. (Some time ago I did an extended blog series on the topic of The Protestant Mary. There is growing interest in Mary among evangelicals and other Protestant Christians.) |

|

|

Above: Poster for The Nativity Story

Below: Cover of The Real Mary |

|

Before too long I'll put up a more extensive review of The Real Mary. But let me show my hand right now and say that this is a fine book. I'd strongly encourage you to buy it, especially in light of the pending release of The Nativity Story.

In order to spur well-informed interest in The Real Mary, Paraclete Press has put up a couple of chapters on its website. Click here if you want to download the PDF file. Check out these chapters and then buy the book. Also, if you are a church leader, contact Paraclete Press about special offers for churches that intend to use The Real Mary for group study.

The Nativity Story: A Fantastic Opportunity

Posted for Friday, November 17, 2006

| A couple of weeks ago I mentioned the soon-to-be-released film, The Nativity Story. I explained that I had seen the script, and was excited about the possibilities afforded by this film. Well, now I've seen an advance screening, and my excitement has been multiplied considerably.

I'll write a more reflective review of the film shortly before its release on Friday, December 1. Today I want to note a few salient points that make The Nativity Story such a fine movie.

1. The movie is faithful to the biblical accounts of Jesus's birth.

The Nativity Story takes the gospel accounts at face value. It doesn't, for example, engage in all sorts of speculation about how Mary came to be pregnant, the sort of thing you find in secular scholarship and anti-Christian websites. Rather, in The Nativity Story, as in the gospels, Mary becomes pregnant by the miraculous intervention of the Holy Spirit. This will bother folks who want to debunk the Christian story, but it will please others, and not only Christians, but also non-Christians who don't need to turn every movie into an axe to grind. |

|

|

2. The movie provides a creative, compelling, and historically-sensible picture of life suggested by but not specifically mentioned in Scripture.

For example, those who wrote the film did their homework with respect to cultural customs and historical realities in Galilee during the time in which Jesus was born. They rightly portray the feeling of what it was like for Jewish peasants to live under the twin terrors of Rome and King Herod the Great. The Nativity Story even provides the "back-story" of the Magi. No doubt some critics will object to the traditional portrayal of three Wise Men from the East. The film even uses the names of these men as they have been passed down in Christian tradition, though there's no biblical record of their names or even really who they were.

If you're looking to The Nativity Story to provide the definitive documentary on the birth of Jesus, then you'll be disappointed. But if you're looking for an excellent bit of creative filmmaking that affirms but goes beyond the biblical material, then you'll be quite pleased. Is this movie exactly what I would make if I had the chance? I doubt it. Is it better than what I would make? No doubt about it. Is it well worth seeing? You bet.

3. The movie doesn't offer up too much religious schmaltz.

I was worried, for example, about how this film might portray the angels. I mean, I love The Glory of Christmas at the Crystal Cathedral, but I was hoping that The Nativity Story would avoid having beautiful blond female angels fly around in the sky. I won't spoil the surprise by telling you how the angelic presence is portrayed in the film. But I will say that I found it to be within the scope of reasonable art, rather like some of the classic paintings of the Annunciation to Mary.

4. The Nativity Story dramatizes aspects of the Christmas story that I had not before considered.

I've studied the birth accounts of Jesus for over thirty years. I've taught on them and preached on them. But certain aspects of the story only now have become real to me. For example, it never dawned on me to think of what Mary must have experienced in her own family as she told the "tall tale" of being miraculously impregnated. I sensed in The Nativity Story the vulnerability of Mary and Joseph in a new way.

5. The Nativity Story does not turn its major characters into glow-in-the dark, other-worldly superman and superwoman.

When you're dealing with Mary and Joseph, your walking on holy ground, and not only holy ground, but holy ground about which many people have strong feelings. I wondered how The Nativity Story would portray these two characters. Overly pietistic? Plastic and unbelievable? Iconoclastic? Or . . . ? What I found was a pleasant surprise. Mary seemed like a real, fifteen-year-old faithful Jewish girl, but not at first a saint in the making. Nothing in the film demeans Mary, mind you. But she isn't envisioned as spending hours in prayer, either. Joseph was portrayed as even more believable, as someone I could relate to in a powerful way. In one of my favorite scenes, he and Mary are talking quietly about their experience of the angel. Joseph said the angel told him not to be afraid. "Are you afraid?" Mary asks. "Yes," he admits. "Me too," Mary agrees. This, it seems to me, captures what was surely the experience of the real Mary and Joseph, even as they faithfully followed the angel's lead and trusted God in an extraordinary way.

6. The Nativity Story includes some stunning scenery and wonderful music.

The movie was filmed on location in Italy and Morocco. In fact, the filmmakers used the ancient city of Matera in Italy, the same location Mel Gibson used for The Passion of the Christ. I'm going to buy the soundtrack by Mychael Danna as soon as it's released (December 5, apparently).

My Recommendations

First of all, be sure to see this movie! It's well worth the price of admission, especially in the season leading up to Christmas.

Moreover, if at all possible, see the film on its opening weekend (December 1-3). Why then? Because opening weekend numbers are what Hollywood execs scrutinize when they consider what sort of movies to make. On the heels of The Passion of the Christ and The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, a strong opening for The Nativity Story would surely lead to the making of other films that reflect faithful Christian values and ideas. (My personal hope is that the opening weekend of The Nativity Story will surpass the opening weekend of Borat by a longshot!)

But, second, don't only see the film, get others to see it! If you're a pastor, let your church know about this movie. If you're a youth leader, tell your kids. If you're a blogger, blog about it. Invite your friends and neighbors.

A note of caution for parents: This film contains a few intense scenes (Roman soldiers, the killing of babies in Bethlehem, and two birth scenese). These are filmed tastefully, without blood. The PG (not PG-13) rating is appropriate. But I don't think I'd bring children under 7 to the film, especially if they're apt to be scared.

If you're inviting folk who aren't Christian, surely let them know that The Nativity Story is a faithful retelling of the Christmas story. No need to pretend. But even non-believers will enjoy this movie, especially when the Christmas season is upon us. There is nothing "preachy" about this film, nothing that would offend a non-believer.

In two weeks The Nativity Story will be opening in over 3,000 theatres around the country (and 8,000 worldwide). This gives you time to make plans to see it, and to tell lots of folks to join you. Please help me in getting out the word!

The Real Mary in Two Genres

Part 3 of the series: The Nativity Story and the Real Mary

Posted for Thursday, November 30, 2006

Tomorrow The Nativity Story will be released in theaters. This film offers a compelling artistic rendering of the story of the birth of Jesus as it's found in the New Testament.

When I saw an advance screening of The Nativity Story, I was struck by its portrayal of Mary. She is not the "glow-in-the-dark" figurine of popular Christian iconography. Nor is she the other-worldly saint of Christian tradition. Rather, Mary is a down-to-earth Jewish girl whose life is forever altered by a miracle of God.

I've spent hours upon hours studying the biblical portrayal of Mary. The portrayal of Mary in The Nativity Story reflects an historically and exegetically defensible understanding of her life. For example, most scholars believe that she was quite young, probably somewhere around fourteen years old when the angel visited her. This calculation reflects both the way she is described in the Bible and an understanding of Jewish culture in the first-century A.D.

| The portrayal of Mary in The Nativity Story was sufficiently sound from an historical point of view to allow me to relax my overactive mind and let Mary's story touch my heart. I was able to see, as never before, just how unsettling Mary's experience must have been. It's one thing to say that her pregnancy would have been scandalous, and quite another to let a work of art help one to feel the whip of disgrace as it cracked upon Mary's young back. Before viewing The Nativity Story, for example, I had never thought about what it must have been like for her to tell her family that she was pregnant, and that she hadn't been sexually intimate with a man. |

|

| |

Keisha Castle-Hughes as Mary |

Thus seeing The Nativity Story helped me to feel for Mary, to get inside her sandals, and to understand just how overwhelming the events associated with Jesus's birth must have been for her. I came away from the film with more respect for her courage and faith. I was also reminded how much God's ways are not our ways.

If The Nativity Story helps us to get in touch with Mary in a new way, so does Scot McKnight's recently-published book, The Real Mary: Why Evangelical Christians Can Embrace the Mother of Jesus. Ironically, or perhaps providentially, this book does with words what The Nativity Story does with film. As an outstanding New Testament scholar who can write for non-specialists, McKnight helps us understand Mary in her historical context. He explains in some detail, for example, what would usually have happened to an engaged girl who became pregnant before she was intimate with her husband. It isn't a pretty picture. But it's a picture against which we can see Mary more clearly, and revere her more freely.

The Real Mary doesn't deal only with the events surrounding the birth of Jesus. McKnight focuses mainly on biblical descriptions of her life, though adding some insights on what came later. Though he is an evangelical Christian, McKnight doesn't go the "Catholic bashing" route. He does, however, show clearly what can be learned from Scripture and what cannot.

Though The Real Mary is a work of popular scholarship, I found myself deeply moved in places. McKnight's portrayal of Mary's gutsy faith caused me not only to admire her, but also to consider my own paltry trust in God. Though not what you'd call an "inspirational" Christian book in the narrow sense, since The Real Mary is mostly filled with wise teaching, I have been truly inspired by reading this book.

As we enter the season of Advent, a time in which we get ready for a fuller, richer celebration of Christmas, I can think of no better way to embrace this season than by getting to know the real Mary in two genres. Don't miss The Nativity Story. And be sure to read The Real Mary by Scot McKnight. Both of these portrayals of Mary will help you get ready to welcome the real Jesus in a new and fresh way.

Mary and the Pain of Serving God

Part 4 of the series: The Nativity Story and the Real Mary

Posted for Friday, December 1, 2006

| The Nativity Story is in theatres today. Go see it! I'm taking my family tonight. |

When we think of Mary's experience as the mother of Jesus, our first thought is of what an incredible honor and blessing it was for her. Mary is, quite arguably, the most blessed of all human beings because she was chosen by God to carry, give birth to, and raise His Son. I can't imagine a more honored and special and wonderful calling for any human being. Indeed, Elizabeth spoke the truth when she cried, "Blessed are you among women!" I'd want to add, "and among men too!"

But I think it's easy for us to miss the pain inherent in Mary's service to God. To be sure, I'm thinking in part of the pain of childbirth. Though I've never experienced this directly, I have pretty close secondhand experience, and that's more than enough to convince me that giving birth must be one of the most painful of all human experiences. The baby Jesus could have shown up in a basket on Mary's doorstep for her to raise. That would have been an easier start for Mary (putting aside the theological issues for a moment).

Yet I'm thinking of other dimensions of the pain associated with Mary's unique role as mother to the Son of God. These dimensions are poignantly dramatized in The Nativity Story and clearly explained in Scot McKnight's book, The Real Mary. I'm thinking about the most obvious downside of the virginal conception, the fact that to most people Mary's pregnancy would appear to be a result of her sexual immorality.

Now in our day, there still are communities that frown upon a woman's getting pregnant outside of marriage, though this practice is increasingly common in our society. In Mary's day, however, getting pregnant apart from marriage, and especially the sexual sin it implied, was just about the worst thing a woman could do. Mary's situation was complicated by the fact that she was engaged to Joseph. In her culture, this meant essentially that she was married, though she and Joseph would live apart for a year and were not allowed to enjoy sexual intimacy together until they shared a common home. As a legally married woman who became pregnant, and not be her fiancé/husband, Mary would have been thought to be an adulteress. The Jewish law is clear about what happens to such a woman: "If a man commits adultery with the wife of his neighbor, both the adulterer and the adulteress shall be put to death" (Leviticus 20:10). We see an example of this law being applied in John 8:1-11. |

|

| |

|

For Mary, the angel's annunciation contained both wonderful and terrible news. On the positive side, she learned that her child would be the long-hoped-for king of Israel, the One who would sit upon the throne of David. It's hard to imagine better news for Mary. Yet, on the negative side, she learned that her pregnancy would come apart from her marriage. She was surely aware of the painful implications of this miracle. She would appear to be an adulteress. She would dishonor her family, perhaps even be disowned by them. She would dishonor her fiancé/husband, and in all likelihood be rejected by him. Moreover, if his anger or sense of righteousness demanded it, he could have her put to death according to the law.

In the best case scenario, Mary would not be stoned to death, but would live her whole life as a woman of questionable morality, somebody about whom people would whisper when she wasn't around, or even when she was. We find evidence of this very thing in Mark 6:3, where Jesus is referred to by the residents of Nazareth as "the son of Mary." Every son, other than one of illegitimate birth, would have been called the son of his father. The phrase "son of Mary" in Mark 6 was equivalent to calling Jesus a bastard, in the literal sense.

As we read Mary's story in Luke 1, especially when we realize the cultural downside of her virginal conception, we cannot help but to wonder at her faithful response to the angel: "Here am I, the servant of the Lord; let it be with me according to your word" (v. 38). Moreover, by the time she sings her magnificent song, which we call The Magnificat, Mary understands that "from now on all generations will call me blessed" (v. 48). To be sure, no human being apart from Jesus Himself has received more honor than Mary. But it's most unlikely that she enjoyed any of this adulation in her own life, at least not until after the resurrection of Jesus. What Mary actually experienced socially was closer to disgrace than grace.

Mary's situation has caused me to reflect upon the strange ways of God. She is perhaps the extreme case of something that has been experienced by millions and millions of God's people throughout history. Just think of it. God chooses the Jews as His special people, but their history hasn't exactly been free from suffering. Jesus chooses twelve to be his closest disciples, and most if not all of them end up being killed for this reason. Ditto the Apostle Paul. Ditto millions of Christian martyrs throughout the centuries.

But even if we're not actually killed for our faith, serving God is often fraught with pain. I recently spoke with a woman in my congregation who has an amazing ministry of writing about people who are experiencing great suffering. God has used her ministry to do amazing things for these people. But this has come at a high cost for her, because she's a person with a tender heart. She doesn't just write about the suffering of people; she weeps over them. God has given her a wonderful calling, yet it is wrapped in pain. God has used her to make a huge difference to help suffering people, and in this she rejoices. But she's also known more pain that most people because of her unique ministry.

I don't think it's an accident that Mary's calling involved pain. This seems to be a part of how God does things. Just think about Jesus, if you want an even more striking example. One of my favorite books is The Wounded Healer by Henri Nouwen. In this tender and wise book Nouwen explains that God works through us, not in spite of, but because of and in the midst of our woundedness. Pain opens our hearts to God, enabling to minister with passion, authenticity, and humility. Though God's call promises innumerable blessings, it also leads to pain and heartache. This isn't the fun part, but Mary's example suggests that it is an essential part of God's work.

The Nativity Story: Did It Really Happen That Way?

Part 5 of the series: The Nativity Story and the Real Mary

Posted for Monday, December 4, 2006

The Nativity Story began playing in theaters this past weekend. Attendance numbers were modest, surely not as strong as some would have hoped (including me). But I fully expect that word of mouth will help this film. I spoke with several people who saw it this past weekend, and every person enjoyed it and found it to be a moving portrayal of the birth of Jesus. My guess is that as we come closer to Christmas, millions upon millions of people will see The Nativity Story, both because of what they hear from their friends and because it offers a marvelous way to prepare for what Christmas is really all about. In fact, if you find yourself piled under by present shopping and holiday partying, let me encourage you to do yourself a huge favor and take a couple hours off to see The Nativity Story. It may be the best nine dollars you'll spend this month.

When you see this movie, no doubt you'll wonder along the way: Did it really happen that way? This is an important question, and one that I want to begin to answer in today's post.

Let me say at the outset that The Nativity Story is not meant to be the definitive presentation of the birth of Jesus. It is nothing like a documentary. Rather, it presents itself as a work of historical fiction, or, better yet, history plus fiction. It is one creative vision of the events surrounding the birth of Jesus. It provides one perspective among many possible perspectives on what an angel might look like, what life in Nazareth was like, what motivated the magi, etc. etc. The movie goes far beyond what is actually found in the New Testament gospels.

Yet it obviously seeks to remain faithful to these gospels. The Nativity Story doesn't engage in some of the historical reconstructions one can find in hyper-critical New Testament scholarship. For example, Jesus is born in Bethlehem, not in Nazareth, as some scholars would allege. And the miraculous elements of the biblical story are fully intact in The Nativity Story, including Mary's virginal conception.

Of course, at this point the house divides with respect to the question of whether the birth of Jesus really happened as portrayed in The Nativity Story. There is no shortage of skeptics who claim that the biblical narratives are themselves filled with legendary fictions. Even the most ardent Christian can see why they come to this conclusion. After all, the gospel stories of Jesus's birth are filled with supernatural elements, including angelic visitations and two miraculous birth (one to Elizabeth, a post-menopausal woman, and one to Mary, a woman who has not been sexually intimate with a man). In general, we don't tend to believe that such things happen. Moreover, if your worldview doesn't allow for such events, then the only sensible conclusion you can draw is that Christians made up the stories about Jesus's birth. So, not unexpectedly, skeptics answer my presenting question–Did it really happen that way?–with a confident "No." In reality, they would claim, Jesus was conceived and born in the ordinary manner, and we simply don't have the historical details.

At this time I don't want to respond to those who dispute the basic historicity of the biblical narratives. I did this a couple of years ago in a blog series entitled: The Birth of Jesus: Hype or History? In that series I acknowledged that we don't have a lot of information about the birth of Jesus. Yet I explained why what we do have is believable if one grants the possibility of things like angelic visits and miraculous conceptions.

What I do want to weigh at this point is the historical accuracy of The Nativity Story if one assumes the basic authenticity of the gospel narratives. In other words, my question is: If we assume that the gospel stories of Jesus's birth are true, does The Nativity Story accurately portray what happened, especially when it goes beyond the biblical accounts?

The Engagement of Mary and Joseph

| In many cases the answer to this question is "Yes." For example, consider the way the engagement/marriage of Mary and Joseph is portrayed in the film. First of all, Mary has nothing to say about her engagement. It is arranged by Joseph and Mary's father. This fits the custom of the time accurately. (In fact, when Mary asks her mother why she has to marry a man she doesn't love, that line is more modern than historical. I doubt the original Mary would have thought such a thing, let alone asked it. The answer would have been too obvious: "Because that's how we do things, Mary.") |

|

| |

Joseph (Oscar Isaac) and Mary (Keisha Castle-Hughes) from The Nativity Story |

Second, The Nativity Story accurately reflects the unusual nature of engagement in first-century Jewish culture. When a man and woman became engaged, they were considered legally married, even though they did not live together or share sexual intimacy for a year. This explains two rather odd but well-informed statements in the Gospel of Matthew:

Now the birth of Jesus the Messiah took place in this way. When his mother Mary had been engaged to Joseph, but before they lived together . . . . (Matt 1:18)

When Joseph awoke from sleep, he did as the angel of the Lord commanded him; he took her as his wife, but had no marital relations with her until she had borne a son . . . . (Matt 1:24-25)

Sometimes people have wondered why Mary, if she was merely engaged to Joseph, would have gone with him to Bethlehem to be registered. In fact, from a legal point of view, they were a married couple, and this explains Mary's going along with Joseph, which we find both in the gospels and in The Nativity Story.

Third, the legal status of Mary and Joseph also accounts for why the movie would portray Mary as liable to be stoned to death. (I'm intentionally avoiding a spoiler here.) From the point of view of the Jewish law, an adulteress deserved the death penalty (Leviticus 20:10). Because an engaged woman was considered to be legally married even though her marriage had not been consummated, Mary was in deep trouble. Her being with child would have been considered impregnable evidence of her having been an adulteress (unless she claimed to be raped).

So, the writer of The Nativity Story (Mike Rich) obviously did his historical homework when it came to the customs and laws for marriage in the time of Jesus's birth. With the exception of Mary's question about why she should marry without love, the portrayal of her relationship with Joseph reflects a nuanced understanding of how things happened at the time.

In my next post I'll consider other ways in which The Nativity Story is (or is not) historically accurate.

Book Recommendations

If you're looking for more information on the history behind the birth of Jesus, let me recommend two fine books. The first I've mentioned before: The Real Mary by Scot McKnight. The second is a very readable discussion of the events concerning the birth of Jesus written by a highly-regarded professor of ancient history, Paul L. Maier. Maier's book In the Fullness of Time is a sane and sober examination of the historical dimensions of the Nativity story. This book also contains Maier's insights on the Easter story and the early church.

The Nativity Story: Did It Really Happen That Way? (Section B)

Part 6 of the series: The Nativity Story and the Real Mary

Posted for Tuesday, December 5, 2006

The Visit of the Magi

Growing up as a Christian, I always pictured the three Wise Men coming to visit the baby Jesus while He was in the manger (thinking incorrectly, by the way, that "manger" meant "stable" rather than "feeding trough"). That's the way my family's nativity scene portrayed reality. And that's also the way the story was played out in church pageants.

Thus, when I first heard the claim that the Wise Men, who were called Magi, didn't come on the night Jesus was born, but sometime thereafter, I was scandalized. Yet this retelling of the Christmas story didn't come from some skeptical critic of Christianity, but rather from a trusted Bible teacher who was doing his best to interpret Scripture accurately. Thus, though I was scandalized, I was also intrigued.

Since that day, I've found that it's commonplace for Christians, especially learned ones, to assume that the Magi did not join the shepherds at the crèche, but instead came to visit Jesus months later. Nevertheless, our manger scenes and Christmas plays tend to preserve the tradition of a concurrent visit by shepherds and Magi, even if this isn't exactly how it happened.

Now comes The Nativity Story, which gloriously places the Magi alongside the shepherds on the night of Jesus's birth. For those of us who have finally come to terms with the fact that the Magi visited well after Jesus's birthday, this comes as a bit of a surprise. So what are we to make of this? Does The Nativity Story relate what really happened?

| At an advance screening of the film that I attended, Wyck Godfrey, one of the movie's producers, was asked about the juxtaposition of shepherds and Magi. He explained that the filmmakers knew that this was not, in all likelihood, how it really happened. They weren't suggesting that this was a historically accurate presentation. Rather, they were presenting a film image that was consistent with traditional Nativity scenes and church pageants. He added that they were concerned that a more historical rendering of the Magi would be distracting to people who are familiar with the beloved traditional picture. |

|

| |

A scene from The Nativity Story, with two shepherds and three magi (from the left: Melchior (Nadim Sawalha); Gaspar (Stefan Kalipha); Balthasar (Eriq Ebouaney). |

In this I tend to agree with Godfrey and his colleagues. It reminds me of the choice Mel Gibson made in The Passion of the Christ to have Jesus carrying His complete cross to Golgotha, even though it's most likely that He carried only the crossbeam. Gibson explained his decision to go with the full cross in light of his worry that viewers would be mightily confused if Jesus had been carrying only a beam, rather than a "t-shaped" cross. Although I think many more people are aware of the later visit of the Magi than the crossbeam issue, I can see why The Nativity Story mirrored the traditional picture of the crèche, rather than going with a more historically probable approach

In fact we know very little about the visit of the Magi. We're not even sure who they were, though it's likely they were scholar/astrologers from Babylon or Persia. But even the revisionist tradition that places their visit well after the birth of Jesus is based on scant inferences from the Gospel of Matthew. For example, it is often assumed that if the Magi had come from the distant "east" (Matt 2:1), and if they had seen a star that coincided with the birth of Jesus, then it would have taken them many months to make the trek to Bethlehem. Moreover, Matthew says that the Magi entered a "house" (Greek oikos) in order to see the "child" (Greek paidion). They did not visit a stable or a cave to worship a "baby" (Greek brephos, so Luke 2:12, 16). Furthermore, Herod's decision to kill all the babies in Bethlehem under two years of age suggests that he believed Jesus had been born earlier than the Magi's visit. So, given these bits of data, it's likely that the Magi did not show up on Jesus's birthday, but rather came sometime thereafter with their belated birthday gifts.

Yet the traditional image of concurrent visits from shepherds and Magi is not impossible, given the possibility (some would say likelihood) that the manger in which Jesus was laid was not in a separate stable or cave, but rather in a part of a house that was used for animals. And, of course, it's possible that whatever star the Magi saw in the sky appeared sufficiently before the actual birth of Jesus to allow them to be present for the birth.

Nobody knows, by the way, exactly what the star seen by the magi actually was. Among those who take the star as a historical fact rather than a Christian fancy, there are a variety of explanations. These are gathered together at a helpful website, if you're interested. The Nativity Story opts for one of the popular theories, namely that the star of Bethlehem was actually a convergence of three celestial bodies: Jupiter, Venus, and a star known as Sharu in the East and Regulus in the West. These three celestial bodies, when brought together, would be very bright, and their meaning would speak of the birth of a king. There's no way to know if this is what actually brought the Magi to Bethlehem, however.

The Nativity Story offers a creative back-story for the magi's visit, showing how they discovered the star and why they interpreted it as they did and why they decided to make the long journey to Bethlehem. The movie also utilizes familiar traditions, such as the existence of three wise men (number not specified in Matthew) and their names (Melchior, Gaspar, Balthasar, dated to the seventh century). The film does not make the mistake of identifying the Magi as literal kings. Perhaps the movie's most ingenious invention, and one that has kicked up a bit negative criticism, is portraying the Magi as having a sense of humor. In my first viewing of the film I found this surprising but not distracting. In my second viewing I liked it quite a bit. Of course there's no way to know whether the real wise men actually cracked wise, but, in my experience, most scholars (and that's what the Magi were) have good senses of humor.

In sum, I'd say that the portrayal of the Magi in The Nativity Story is historically plausible. But, given how little we know about these men, it is one of the more creative elements in the film. The timing of the magi's visit to Bethlehem in The Nativity Story is unlikely, but since the movie is a work of art rather than a documentary, I don't find this bit of poetic license to be upsetting.

Book Recommendations

If you're looking for more information on the history behind the birth of Jesus, let me recommend two fine books. The first I've mentioned before: The Real Mary by Scot McKnight. The second is a very readable discussion of the events concerning the birth of Jesus written by a highly-regarded professor of ancient history, Paul L. Maier. Maier's book In the Fullness of Time by Scot McKnight. The second is a very readable discussion of the events concerning the birth of Jesus written by a highly-regarded professor of ancient history, Paul L. Maier. Maier's book In the Fullness of Time is a sane and sober examination of the historical dimensions of the Nativity story. This book also contains Maier's insights on the Easter story and the early church. is a sane and sober examination of the historical dimensions of the Nativity story. This book also contains Maier's insights on the Easter story and the early church.

The Nativity Story: Did It Really Happen That Way? (Section C)

Part 7 of the series: The Nativity Story and the Real Mary

Posted for Wednesday, December 6, 2006

King Herod

King Herod plays a major role in The Nativity Story as the archetypal bad guy. He is seen as a tyrant who taxes his people beyond what they can reasonably pay. His soldiers are portrayed as bullies who care little for the lives of Herod's subjects. The king is also seen as a visionary architect, whose grandiose plans add to the oppressive taxation of his people. Above all, Herod is a power-hungry ruler who seeks to preserve his sovereignty no matter what. He doesn't hesitate to kill many infants in Bethlehem in order to make sure that the Messiah doesn't arise from the line of David.

I found the portrayal of Herod in The Nativity Story to be one of the strongest aspects of the film when viewed from a historical perspective. Of course most of the scenes featuring Herod are fictional, but they are based on a solid historical understanding of the man and his rule. |

|

| |

Ciarán Hinds as King Herod

|

For example, Herod was indeed a visionary architect who oversaw a massive building program, including the extraordinary expansion of the temple in Jerusalem, sometimes known as "Herod's Temple." And, indeed, his construction efforts did require heavy taxation of the people, something that turned them against him. Ironically, Herod began at the young age of 25 as a popular governor of Galilee. But, in time, his ravenous hunger for power, combined with his tendency to over-tax his subjects, led to popular disfavor.

The Nativity Story rightly hints that family squabbles were a major problem for Herod. We see this especially in a scene on a balcony of Herod's palace, in which the king is speaking with his son, Herod Antipas (the Herod who will be tangentially involved years later with Jesus's crucifixion). Herod accuses Antipas of opposing his rule. The ever-cool Antipas reassures his father, who reminds Antipas about what happens to family members who betray him. They are "No more," Antipas states. In fact, Herod did kill members of his own family who, he believed, were a threat to him, including one of his wives. And Herod's tendency to get married often–he had ten wives in total–did contribute to his headaches, since his wives were continually scheming to get their sons to inherit the king's power.

Throughout The Nativity Story Herod is worried about "the prophecy" of a new king for Israel. While this oversimplifies the complex matrix of messianic expectations in the time of Herod, it does point to a solid underlying reality. During the reign of Herod over the Jews, many (most?) of the people yearned for the coming of another king, the true king of Israel. The movie's portrayal of Herod's prophetic paranoia is too simple, but nevertheless on track.

Herod is perhaps most infamous for the so-called "Slaughter of the Innocents," the killing of all the babies in Bethlehem under two years of age. In this way, according to the Gospel of Matthew, Herod sought to protect his power and that of his sons by killing off the newborn king. This is a feature of the New Testament narrative that is frequently disputed by critical scholars, largely because we have no record of this slaughter besides what we find in Matthew. If it really happened, some have argued, we'd know about it from other sources. Therefore Matthew (or his sources) must have made it up.

This scholarly conclusion reflects, among other things, a skeptical bias concerning the historical accuracy of the New Testament gospels. I've written a great deal on this: see Are The New Testament Gospels Reliable? and The Birth of Jesus: Hype or History? And, in fact, I have a book coming out next June that is based on the gospels blog series. It's called Can We Trust the Gospels? Nevertheless, it's certainly fair to ask two questions about the Slaughter of the Innocents:

1. Is it reasonable to believe that Herod would have ordered such a thing?

2. Is it reasonable to believe that this incident would not be recorded in other writings, especially the histories of Josephus?

The response to the first question is surely "Yes." Any man who would murder his own relatives, including his wife, in order to preserve his power wouldn't think twice about killing a bunch of babies in hopes of disposing of the Messiah who would dethrone him (or one of his sons). In fact, we can be almost certain that if Herod actually believed the future king of Judea was a baby in Bethlehem, he'd try to kill that baby. This doesn't prove that it happened, of course. But it does prove that it's possible.

The response to the second question is also "Yes." Although the killing of babies in Bethlehem was surely traumatic for those involved, it wasn't big news beyond this small town. Not too long after Herod's death, some Jews revolted and 2,000 were crucified at one time by the Romans. This event is recorded in the writings of Josephus, but it merits only one sentence (Antiquities 17.10.10). Given the small size of Bethlehem in the time of Herod, his order impacted perhaps a dozen children. Please understand that I'm not trying to minimize the horror of this for those involved. But, given the sort of things that happened under Herod's (and Roman rule), the killing of a few children might easily be overlooked.

If this seems unlikely, consider the case of modern-day Iraq. After Saddam Hussein was deposed, we discovered many mass graves filled with the bodies of people who had been killed by Saddam's regime. Many of these graves and the massive killings that preceded them were unknown earlier. Now surely they were known to the relatives whose loved ones had been murdered. But even in our day of mass media, a tyrant's killings could be hidden. No doubt if Saddam had killed a dozen babies in a remote village peopled by his enemies, it would easily have been overlooked by journalists and historians. Similarly, how many innocents have been slaughtered in Sudan, people whose experiences will never be widely known even in our day?

Since I take Matthew to be a trustworthy historical source, given the propensities and limitations of his culture, I find it reasonable to believe that the Slaughter of the Innocents did, in fact, occur. The timing of this event as portrayed in The Nativity Story may be a bit inaccurate, however, since it's not likely that the slaughter happened so close to Jesus's birthday. Yet the portrayal of this event, and of its author, King Herod, shows, once again, that the writer of The Nativity Story did his homework. His portrayal of Herod rings true.

Book Recommendations

If you're looking for more information on the history behind the birth of Jesus, let me recommend two fine books. The first I've mentioned before: The Real Mary by Scot McKnight. The second is a very readable discussion of the events concerning the birth of Jesus written by a highly-regarded professor of ancient history, Paul L. Maier. Maier's book In the Fullness of Time by Scot McKnight. The second is a very readable discussion of the events concerning the birth of Jesus written by a highly-regarded professor of ancient history, Paul L. Maier. Maier's book In the Fullness of Time is a sane and sober examination of the historical dimensions of the Nativity story. This book also contains Maier's insights on the Easter story and the early church. is a sane and sober examination of the historical dimensions of the Nativity story. This book also contains Maier's insights on the Easter story and the early church.

The Nativity Story: Did It Really Happen That Way? (Section D)

Part 8 of the series: The Nativity Story and the Real Mary

Posted for Thursday, December 7, 2006

Was Jesus Born in a Cave?

I grew up with a clear picture of the place Jesus was born. I can still remember my mother's nativity set with its humble wooden stable. This vision of a small, barn-like structure was confirmed in Christmas pageants at church. After the innkeeper uttered the infamous "no room" line, Mary and Joseph ended up in a simple wooden stable, at the center of which was a basic wooden feeding trough, the manger. (In my youth, I mistakenly thought that "manger" meant "stable," when in fact it referred not to the building, but to the trough out of which the animals in the stable ate.)

In The Nativity Story, Jesus is born, not in a wooden stable, but in a cave that serves as a stable for animals. What are we to make of this? |

|

| |

No stable here, but my wife, daughter (!), and I do have a traditional manger. |

I first heard the idea that Jesus was actually born in a cave from my ninth grade history teacher, who was trying to show how Christianity had borrowed from other religions. "Tradition holds that Jesus was born in a cave," he announced, "just like the Persian god Mithras." This cave-tradition was new to me, and troubling because it seemed to imply that the Christians made up the story of the birth of Jesus by borrowing from ancient Persian myths. (You can still find people making this argument, by the way, though it fails on many counts.)

Later I learned that the tradition of Jesus's birth in a cave was very old, going back at least to the second-century A.D. It is found, for example, in the writings of the orthodox church father Justin Martry (Dialogue with Trypho 78:4). In fact, there are a number of small caves around Bethlehem, and it's likely that some of these were used as stables for animals. During the second or third century, the Romans sought to desecrate the Christian holy sites, and erected a shrine for the god Adonis in a cave in Bethlehem. Then, in the early fourth century, the Roman Emperor Constantine erected a basilica over the cave that was believed to be the birthplace of Jesus. Today this is the location of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, which Christians widely revere as the place where Jesus was born.

The New Testament does not locate the birth of Jesus in a cave. Yet it doesn't support the solitary wooden stable theory either. Here is what we have to go on from Luke 2:7: "And she gave birth to her firstborn son and wrapped him in bands of cloth, and laid him in a manger, because there was no place for them in the inn." The word "manger" translates the Greek word phatne, which means "feeding trough." From this word, which is repeated in the angelic message to the shepherds (Luke 2:12, 16), we get the idea that Jesus was born in a place where animals were fed, that is, some sort of stable. At this time and place, the average manger wasn't made of wood, but rather of stone. (I'm almost sure the manger in The Nativity Story was made of stone.)

Jesus was born there, Luke says, "because there was no place for them in the inn" (2:7). This phrase is the basis of the oft' repeated scene in Christmas pageants, where the usually stern innkeeper denies space to Mary and Joseph. The Nativity Story hints in the direction of this tradition, but does not have Joseph knocking on the door of the Motel 6 in Bethlehem. In fact, most scholars believe that the word translated as "inn" in Luke 2:7 (katalyma in Greek) probably meant something more like "guest room." Some have even denied that Bethlehem would have had an actual inn, given its small size and lack of prominence.

We get some help from Luke himself when we're trying to decipher the meaning of katalyma, whether it means "inn" or "guest room." In the story of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:34), the Samaritan took the attacked man to an "inn." Here Luke uses the Greek word pandocheion, which clearly means "place of lodging for visitors (including men who have been robbed and beaten, I guess)." Later, in his description of the preparations for the Last Supper, Luke has Jesus refer to the room in which He and His disciples will gather as a katalyma (Luke 22:11). In context, this clearly refers to the "upper room" (anagaion, 22:12) of a house.

The better-than-average home in Bethlehem would have had a room that served to house guests, a katalyma. It also would have had a place for animals, either under the main living quarters (rather like a modern-day carport), or nearby. This stable would have had a manger for the animals. And the stable might have been in a nearby cave.

So, the most plausible understanding of Luke 2:7 would be that Jesus was born in a stable for animals, a room that was part of a home or adjactent to it. The stabel could have been a small cave, given the geology of Bethlehem. The reason Jesus was not born in more humane surroundings was not because Bethlehem's official inn was full, but rather because the guest room of the home associated with the stable was already filled with visitors (perhaps Joseph's relatives) who had come to Bethlehem in response to the order of Augustus. Lest we think poorly of the people in the guest room who didn't make room for Mary and Joseph, it may be that the stable would have been better than a crowded house for giving birth. A clean stable would have afforded a measure of privacy not to be found in the katalyma.

In sum, I would conclude that The Nativity Story's version of events in Bethlehem leading up to Jesus's birth is plausible, though by no means certain. The movie is on solid ground to omit the traditional innkeeper at the door scene, though there is a downsized version of this tradition in the film (where the "no room" person seems to have a crowded guestroom rather than an inn with no vacancy). Putting Jesus's birth in a stable-cave fits with the oldest Christian tradition, even though we can't be sure what sort of stable served as Jesus's first shelter.

Of course whether Jesus was born in a stable attached to a home, or in a nearby cave, the fact that He began life in such humble surroundings is most striking. One would never expect the Jewish Messiah, not to mention the Word Incarnate, to enter the world in such utter humility. Whatever the historical details might be, the wonder and mystery of the Incarnation is powerfully depicted in Luke's terse narrative and in the imaginative vision of The Nativity Story.

Book Recommendations

If you're looking for more information on the history behind the birth of Jesus, let me recommend two fine books. The first I've mentioned before: The Real Mary by Scot McKnight. The second is a very readable discussion of the events concerning the birth of Jesus written by a highly-regarded professor of ancient history, Paul L. Maier. Maier's book In the Fullness of Time by Scot McKnight. The second is a very readable discussion of the events concerning the birth of Jesus written by a highly-regarded professor of ancient history, Paul L. Maier. Maier's book In the Fullness of Time is a sane and sober examination of the historical dimensions of the Nativity story. This book also contains Maier's insights on the Easter story and the early church. is a sane and sober examination of the historical dimensions of the Nativity story. This book also contains Maier's insights on the Easter story and the early church.

The Nativity Story: Foreshadowings

Part 9 of the series: The Nativity Story and the Real Mary

Posted for Friday, December 8, 2006

This will be my last post for now in the series The Nativity Story and the Real Mary. In recent posts I've been commenting on the historical plausibility of The Nativity Story's version of the birth of Jesus. Today I want to examine its artistic and theological vision by focusing on elements of the film that foreshadow what is to come in the life of Jesus.

Prophecies

Of course the angelic prophecies to Zechariah and Mary most obviously point to future events, including John's preparation of the people for the Lord and Jesus's actions as Messiah and Savior. If my memory serves me correctly, in The Nativity Story the prophecies delivered to Zechariah and Mary were close paraphrases of the biblical text.

Antipas

| As I explained in an earlier post, Herod Antipas, son of Herod the Great, plays a minor but significant role in The Nativity Story. Toward the end of the film, he seeks to encourage his paranoid father by saying, "The prophecy will end tonight. The sons of Bethlehem shall be no more." Of course there's a fine bit of irony here, in that one of these "sons of Bethlehem" will turn out to be a thorn in the side of Antipas when he grows up. The Gospel of Luke reveals that Antipas in fact wanted to kill the grown up Jesus (Luke 13:13). Later, Antipas played a small role in the trial of Jesus (Luke 23:6). |

|

| |

Alessandro Giuggioli as Antipas (left) and Ciarán Hinds (Herod) in The Nativity Story

|

Crucifixion

Crucifixion shows up in at two scenes in The Nativity Story. The images of crucified men serve mostly to underscore the brutality of Herod's and Roman rule. But they subtly point to what will someday happen to Mary's baby.

Foot Washing

One of the most tender scenes in The Nativity Story happens as Mary and Joseph are making their long trek from Nazareth to Bethlehem. Mary notices that Joseph's feet are sore and bleeding. Later, when he is resting, she washes his feet. Seeing Mary washing the feet of Jesus's earthly father, I couldn't help but remember a scene from the Gospel of John where another Mary anointed the feet of Jesus and wipes them with her hair (John 12:3). Ironically, as Mary serves Joseph by washing his feet, she testifies to his own servant's heart as she speaks to her baby: "You will have a good and decent man to raise you. A man who will give of himself before anyone else."

Myrrh

According to Matthew 2:11, the Magi presented gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh to Jesus. This is faithfully depicted in The Nativity Story. Yet the movie adds words of interpretation from each of the Wise Men. Melchior presents gold to "the king of kings." Gaspar offers frankincense to "the priest of all priests." Balthasar, when presenting his myrrh to Jesus, says, "A gift of myrrh to honor thy sacrifice."

Indeed, myrrh was used in the ancient world not only for perfume, but also for embalming. It shows up in the gospels not only as one of the Magi's gifts, but also in the context of the death of Jesus. When He is dying on the cross, Jesus is offered "wine mixed with myrrh" (Mark 15:23). And He is buried along with "a mixture of myrrh and aloes, weighing about a hundred pounds" (John 19:39). For those who are unaware of the connection between myrrh and Jesus's death, The Nativity Story makes it clear through the words of Balthasar.

The Empty Manger

The Nativity Story condenses the events that follow the birth of Jesus. As I explained earlier in this series, it's most likely that the Magi came to visit Jesus, not on His birthday, but sometime thereafter. Herod's Slaughter of the Innocents also happened a good chunk of time after Jesus's birth. In the movie, all of this happens on the same day of Jesus's birth, more or less. Thus as they leave Bethlehem to flee to Egypt, Joseph and Mary take Jesus right from the manger.

When one of Herod's soldiers, seeking to kill any baby who might be hiding in the stable-cave, looks into the cave, he sees an empty stone manger with a cloth left behind. The combination of cave, manger, and cloth suggests another scene, one that will come some thirty years later. In this scene, Peter, one of Jesus's disciples, comes on Easter morning to investigate the tomb in which Jesus had been buried. As he enters the tomb, he sees the place where Jesus had been laid now empty except for the linen cloths that had wrapped the body of the crucified Jesus.

I wouldn't be surprised if there are more foreshadowings in The Nativity Story, scenes I have overlooked or forgotten. If you notice any when you see the movie–and I strongly recommend that you do see it–drop me an e-mail to let me know.

I appreciate the way this film points ahead to the ultimate meaning of Jesus's birth without being so obvious as to make it seem like a sermon. I'm just fine with sermons. In fact I preach them all the time. But I prefer my movies to use art and subtlety rather than sermonizing. The Nativity Story does this quite sweetly.

Book Recommendations

If you're looking for more information on the history behind the birth of Jesus, let me recommend two fine books. The first I've mentioned before: The Real Mary by Scot McKnight. The second is a very readable discussion of the events concerning the birth of Jesus written by a highly-regarded professor of ancient history, Paul L. Maier. Maier's book In the Fullness of Time by Scot McKnight. The second is a very readable discussion of the events concerning the birth of Jesus written by a highly-regarded professor of ancient history, Paul L. Maier. Maier's book In the Fullness of Time is a sane and sober examination of the historical dimensions of the Nativity story. This book also contains Maier's insights on the Easter story and the early church. is a sane and sober examination of the historical dimensions of the Nativity story. This book also contains Maier's insights on the Easter story and the early church.

Home

|