| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

Love Your Enemies.

Jesus on Love. Loving Enemies.

An Even More Inconvenient

Truth:

Love Your Enemies

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2007 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com. Thank you.

An

Even More Inconvenient Truth

Part 1 of series: An Even More Inconvenient Truth

Posted for Tuesday, February 27, 2007

Al Gore and Leonardo DeCaprio,

as Gore is interrupted by the

Academy Awards orchestra

|

As expected, Al Gore's global warming film, An Inconvenient

Truth, won the Oscar for Best Feature-Length Documentary.

Whatever you may think of Gore or his movie, you've got to

admit that Gore supplied one of the funniest moments in the

Academy Award program. It came early in the show, when he and

Leonardo DiCaprio took the stage to explain how the Oscars

had gone "green." DiCaprio, in a pleading voice,

asked Gore for the second time if he had "any other major announcement" to

make. Gore got choked up, and said something like: "Well,

given the overwhelming support I've received, I'd like to make

an announcement." Removing a written speech from his pocket,

Gore continued, "My fellow Americans . . . ." But

then the orchestra started up, cutting off the former Vice

President as if he were an overly loquacious award winner.

So much for his big announcement! It was a cleverly humorous

moment.

Al Gore believes that global warming is "an inconvenient

truth," and he has devoted himself to spreading the word.

In this series I'm not planning to consider Gore's convictions

or his mission. Rather, I want to focus on another "inconvenient

truth," one I consider much more troubling than global warming.

This truth doesn’t come from Al Gore, but from Jesus. And

if we were to take it seriously, it would change our lives far

more than our thermostats or our MPG ratings.

I'm thinking of the inconvenient truth that appears both in

the Gospel of Matthew and the Gospel of Luke. It proclaims, simply: "Love

your enemies" (Matt 5:44; Luke 6:27, 35). "Love your

enemies" is often held up as the core teaching of Jesus.

It's often praised as evidence that Jesus was an outstanding

religious teacher. But if it's really true that we should love

our enemies, I'd suggest that this is extremely inconvenient.

Why is it inconvenient? Well, for one thing, most of us don't

do this. If we should be loving our enemies, then we'll need

to change some basic behaviors, and this is never easy. Moreover,

many of us, even if we are Christians, have doubts about the

relevance of Jesus's teaching. Surely it doesn't apply to

all of life, we reason. Surely we're not supposed to let

people injure us. And surely we're not supposed to feel warm

affection for Al-Qaeda terrorists who'd be perfectly happy to

blow us up. So what are we to do with the clear and clearly inconvenient

teaching of Jesus to love our enemies?

Recently I preached on this text for my congregation at Irvine

Presbyterian Church. Some of what appears in this blog series

will be based on that sermon. I decided to begin by dealing,

not so much with the broader theological and ethical implications

of loving one's enemy, but rather with the practical, real life

challenges we face each day. I'll do the same in this series,

though ending with a few reflections on how love for enemies

might impact our thinking about things like war.

My decision to focus at first on the practical was motivated,

in part, by what Jesus said about hearing and doing His word:

“Why do you call me ‘Lord, Lord,’ and do

not do what I tell you? I will show you what someone is like

who comes to me, hears my words, and acts on them. That one

is like a man building a house, who dug deeply and laid the

foundation on rock; when a flood arose, the river burst against

that house but could not shake it, because it had been well

built. But the one who hears and does not act is like a man

who built a house on the ground without a foundation. When

the river burst against it, immediately it fell, and great

was the ruin of that house.” (Luke 6:46-49)

No matter how we might apply the teaching of Jesus to the larger

issues of national and international politics, I want to help

us hear and do the word of Jesus in our daily lives. I'm convinced

that obedience to the word of Christ is absolutely foundational for

anyone who wants to be a faithful follower of Jesus.

So, then, here's my basic question for this series: How

can we love our enemies? I'll start to answer this question

in my next post.

A

Confession of Limited Perspective

Part 2 of the series: An Even More Inconvenient Truth

Posted for Wednesday, February 28, 2007

Yesterday I began a blog series that seeks to answer a simple

question: How can we love our enemies? The answer to

this question, as you may have guessed, is not nearly so simply

as the question itself.

As I begin this series, I should confess my limited perspective

and life experience. Though there have been some people in my

life who have sought to hurt me and make my life miserable, I've

never had enemies in any strong sense, surely not in the way

that some people have enemies. I talked about this in my book, No

Holds Barred. Allow me to quote a few paragraphs from Chapter

6 of this book:

I was first confronted by my limited experience of injustice

many years ago as I led a Bible study at a community college

in Los Angeles. The students who gathered to study were diverse:

ethnically, socially, economically, politically, and theologically.

Apart from living in Southern California and believing in Jesus,

we had very little in common.

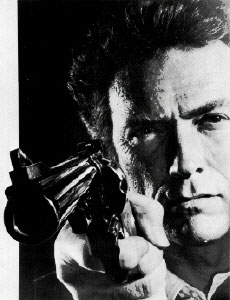

Clint Eastwood, perhaps the most

famous alumnus of Los Angeles City College is someone

who, when in character, isn't especially committed to loving

his enemies.

|

One afternoon I was leading a study of Jesus’s command: “Love

your enemies!” (Matthew 5:44). When I suggested rather

glibly that God always helps us love those who hurt us, a man

named Ricardo interjected, “Yes, but sometimes it’s

very hard to love your enemies.” I agreed, but once again

made such love sound rather simple. Ricardo kept emphasizing

how difficult it was. Finally I asked, “Ricardo, do you

have a hard time loving your enemies?”

“Yes,” he explained, “a very hard time.” He

then told a gripping story. When he was a teen-aged Christian

in Central America, he was part of a Christian evangelistic

movement. He and his friends shared the good news of Jesus

with their neighbors. They had no political agenda. But that’s

not how the government saw their activity. Fearing that Bible-believing

followers of Jesus would become politically uncooperative,

local officials ordered Ricardo and his friends to cease their

evangelistic efforts. They refused to comply out of faithfulness

to Christ. Not long afterward, while they were holding a prayer

meeting, police stormed the meeting hall. They grabbed the

leaders, took them outside, and shot them. Ricardo somehow

escaped. He ran home, gathered his few possessions, and began

the long trek that ultimately brought him to California.

When Ricardo finished his story my heart was deeply moved,

and also ashamed. I realized how cut off I was from the real

suffering of God’s people.

I share this story with you not to suggest that I shouldn't

speak about loving enemies. Indeed, my goal is to pass on Jesus's

wisdom on the topic, not my own. And Jesus surely knew plenty

about having enemies. But I think it's important for me to acknowledge

that I haven't experienced the need to love the sort of enemies

that many people in our world face each day. This means that

my exposition runs the risk of superficiality.

You might be inclined to respond: "But you do have real

enemies. There are Islamic radicals who would be only too happy

to kill you. And you spent much of your life living under the

threat of nuclear annihilation from Soviet nuclear weapons. So

you do have real enemies." I agree with this observation.

But it would be more pertinent if, for example, I had lost a

loved one in the 9/11 disasters, or if I were serving in the

U.S. armed forces in Iraq. In my daily life, the only Muslims

I know, who live three doors down from me, are gracious people,

about as far from enemies as anyone could be. So I've never been

face-to-face with an enemy who wished to take my life.

One might be inclined to say that most of us in the United States

don't really have the chance to love our enemies, and therefore

the teaching of Jesus is irrelevant to us. I believe, on the

contrary, that Jesus Himself shows how His command to love enemies

does in fact relate to the kinds of situations we regularly face

in life. I'll explain what I mean in my next post.

Love

Your Enemies: First Steps

Part 3 of the series: An Even More Inconvenient Truth

Posted for Thursday, March 1, 2007

Jesus said: "Love your enemies" (6:27). No doubt this

shocked his original hearers even more than it shocks us today.

After all, we've heard the "Love your enemies" line

before, and it's been praised by many as exemplary ethics. Such

wouldn't have been the case for Jesus's first audience. In fact,

some Jews in Jesus's day even encouraged, not love for enemies,

but hatred of them. Moreover, in context, the mention of enemies

would have immediately suggested to Jesus's listeners both the

Romans and their oppressive, self-serving vassals, the Herods. Love

our enemies? Jesus's audience must have must have wondered, How

can Jesus be serious?

Another kind of "first steps"

|

It's important to note that loving one's enemies has little

to do with affection for them. Jesus is not saying, "You

should feel lots of warm fuzzies for the Roman soldiers who terrorize

you." Christian love is never primarily a matter of emotion,

but of action. To love is to act intentionally for the best interest

of another. In typically Semitic fashion, Jesus explains what

love for enemies entails by adding several parallel imperatives:

Love your enemies.

Do good to those who hate you,

Bless those who curse you,

Pray for those who abuse you. (Luke 6:27-28)

In other words, loving means doing good to, speaking well of/to,

and praying for people.

So what does this mean for us today? We can get tripped up by

the word "enemies," because most of us don't have full-fledged

enemies in our daily lives, as I explained in my last post. Sure,

we might identify Al-Qaeda radicals as our enemies, but most

of us won't have the chance to engage with them so as to show

love to them.

Does this mean the teaching of Jesus is irrelevant to us? Not

at all. In fact, the word translated in Luke 6:27 as "enemies" can

have a broader sense, referring to those who oppose us in one

way or another. Following Jesus's parallelism, your enemies would

include those who hate you, curse you, or abuse you. They are

the people who treat you badly, unfairly criticizing you, maliciously

gossiping about you, undermining you at work, chewing you out

at home, and so forth. Your enemies may not want to take your

life, but they do want to knock you down a few pegs, to wound

your heart and your reputation.

Jesus says we're to love these people, to do good to them, to

bless them, and to pray for them. This implies that we are not

to return evil for evil. If somebody cusses you out, don't cuss

back. If somebody says mean things behind your back, don't say

mean things behind their back. If somebody cuts you off in a

meeting, don't cut them off. When your spouse hurts your feelings,

don't hurt back.

Yet Jesus calls for more than simple non-retaliation. He

challenges us to do good to those who wrong us. To the

one who cusses you out, speak kindly. When somebody says mean

things behind your back, say positive things about that person

to others. When somebody cuts you off in a meeting, listen

attentively to that very person. When your spouse hurts your

feelings, offer kindness in return.

You may be thinking right now: This is crazy! Well,

you're getting close to the truth, because God's ways are not

our ways. They can look to us like craziness from a commonsensical

point of view. But if God's kingdom has come in Jesus, then we're

going to need a thoroughgoing change of mind. We're going to

need to see things and value them differently. We're going to

need what Jesus calls repentance.

As you hear what Jesus is saying and consider obeying it, you

might also be thinking: This is impossible! I can't do this! If

this thought has struck you, then you're getting close to a crucial

truth. Yes, you can't do it . . . in your own strength. You'll

only be able to do what Jesus commands with God's strength as

God empowers you through the Spirit.

So, then, let me ask you: How do you treat your "enemies"?

Really? Are you apt to retaliate when you are wronged? To fight

back? To get even? Jesus says, "Knock it off. Don't do that

anymore." But He goes still further, calling you and me

to love those who mistreat us, to offer kindness to those who

have been unkind to us. And when you respond, "I can't do

that," Jesus say, "I know. I'll help you."

I'm not suggesting this is easy, even with Jesus's help. In

fact, doing good to those who have wronged me is one of the hardest

things in my life. But if we seek to be faithful followers of

Jesus, then this is our calling.

Before I move on, I want to encourage you to take most literally

the command of Jesus to "pray for those who abuse you." If

you have been mistreated by people at work, or in your family,

or in this church, ask yourself: "Have I been praying for

them?" In most cases, the answer is "No." A starting

point for loving our enemies is praying for them, faithfully,

honestly, graciously, humbly.

Turning

the Other Cheek

Part 4 of the series: An Even More Inconvenient Truth

Posted for Tuesday, March 6, 2007

I'm picking up where I

left off a few days ago, having begun explaining what Jesus

meant when He said that we're to love our enemies.

Jesus expounded still further on what it means to love our enemies

by saying, "If anyone strikes you on the cheek, offer the

other also" (6:29). When we hear this today, we tend to

think that Jesus was describing an act of physical violence.

We interpret Him as saying, "Don't fight back when you're

attacked." But, in context, striking on the cheek wasn't

so much about inflicting pain as it was about doling out shame.

In fact, one commentator notes, "The blow on the right cheek

was the most grievous insult in the ancient Near East." (IVP

Bible Background Commentary: New Testament © 1993 by

Craig S. Keener. Electronic text hypertexted and prepared by

OakTree Software, Inc. Version: 1.0) We might paraphrase Jesus's

teaching this way: When somebody insults you and wounds your

pride, don't defend yourself and don't retaliate.

Again, let's acknowledge how hard this is, impossible, really,

without divine help. Everything in us and everything in our culture

says: Stand up for yourself! Get even! Hit back! Don't be a wimp!

Yet Jesus says, "If anyone strikes you on the cheek, offer

the other also."

I do want to remind you, however, that Jesus doesn't expect

us merely to take what people dish out without any response.

You may recall that in Matthew 18 Jesus said, "If another

member of the church sins against you, go and point out the fault

when the two of you are alone. If the member listens to you,

you have regained that one" (18:15). Then, if this doesn't

work, you're to take along a couple others to help bring about

reconciliation. So Jesus isn't telling us to be everybody's doormat.

There is an appropriate way to respond to wrong done against

you. But what you're not to do is to retaliate in the ordinary,

expected, all-too-human way.

|

I should also warn us at this point not to misconstrue Jesus's

teaching so that sin is ignored, minimized, or excused. Some

people, for example, have interpreted turning the other cheek

to mean that if a woman is physically abused by her husband,

she should just take it. But, in fact, Jesus is not addressing

such a horrible act of brutality, but rather a case of insult.

Moreover, if a woman is being mistreated by her husband, it's

her duty and the responsibility of her Christian community to

confront the abuser directly. It's not even loving to let a person

continue in his sin without calling him to repentance, let alone

to let a Christian sister to be hurt by her husband.

Over the years, I've watched prominent Christian leaders as

they receive criticism, even cruel insults. Some seem to believe

that Jesus's call to turn the other cheek is no longer relevant,

at least not to them. When they are struck with harsh words,

they send harsh words right back. But then I've watched other

Christian leaders exemplify the counter-cultural and counter-intuitive

way of Jesus. Most recently, I was struck by the way Rick Warren

responded to the virulent criticism he endured because he invited

Barack Obama to speak at Warren's church in a conference on AIDS/HIV.

Many Christians slapped Warren's cheek with their harsh words.

But Warren refused to slap back. Now whether you support Warren's

decision to invite Obama to his church or not, you have to respect

Warren's exemplary response. In my opinion, many of Warren's

critics would do well to consider how Jesus's call to love their

enemies is relevant when they're upset with a brother in Christ.

Give to Everyone

Who Begs from You

Part 5 in the series: A More Inconvenient Truth

Posted for Wednesday, March 7, 2007

You can see my dorm, Straus Hall, in the center of this picture. My bedroom

window lies within the red box.

|

Jesus said, "Give to everyone who begs from you" (6:30).

This sounds simple enough to follow, but I can't tell you how

many debates I have been in with other Christians about this

particular verse. When I was in college, my friends and I dealt

with this issue almost daily, because there were many beggars

in Cambridge, Massachusetts. During my freshman year, my dorm

sat right on Harvard Square. I couldn't go to the bank or get

an ice cream cone from Brigham's without running into folks who'd

ask me: "Got a qwa-tuh?" (That's Bostonian for "Do

you have a quarter, please?")

Then, I spent my first seven years of professional ministry

on the staff of the First Presbyterian Church of Hollywood. In

any given week we had literally hundreds of street people coming

to the church looking for financial assistance. It was truly

impossible for us to give to everyone who begged from us. We

had neither enough time nor enough stuff. Moreover, there was

the perennial problem of what people would do with what we gave

them. Money would, in many cases, be used for cigarettes or alcohol.

Food vouchers would often be sold on the streets, with the proceeds

supporting unhealthy habits. Literally following the command

of Jesus seemed to be enabling harmful behavior, not helping

people in genuine need.

So what do we do with the command of Jesus to "Give to

everyone who begs from you"? It's true that in the time

of Jesus most beggars needed the basics of food and shelter,

and wouldn't have squandered their alms on unnecessary and unwholesome

items. Moreover, it's also true that Jesus wasn't laying out

here a systematic ethics of charitable giving. He was using hyperbole–exaggeration,

if you will–to get His audience's attention and to make

a striking point. God help us not to blunt this point with our

rationalizations! Yes, it might in fact be true that there are

times when we ought not to give to one who begs, or at least

we should not give what that person asks. But our habit, our

pattern, our inclination should always be in the direction of

generosity. Better to err by giving away too much than by withholding

too much.

Will we be deceived sometimes? No doubt. Will we feel ripped

off? I'm sure of it. I've felt this way dozens of times throughout

my life. But then I remember that Jesus said, "From anyone

who takes away your coat do not withhold even your shirt," and "if

anyone takes away your goods, do not ask for them again" (Luke

6:29-30). I'm quite sure that when I finally stand before the

judgment throne of Christ, He won't say to me: "Mark, you

were too generous. You were a patsy. You gave away too much."

Do to

Others as You Would Have Them Do to You

Part 6 in the series: A More Inconvenient Truth

Posted for Thursday, March 8, 2007

Today is a special day for my family, literally. March 8th is

what we call "Gary's Special Day." On this day in 1961

we adopted my brother Gary. It was one of the greatest days of

my life. Every year thereafter as I was growing up we'd do something

fun as a family. For Gary, it was like having a second birthday.

My brother Gary showing his prowess as a bowler. Professionally, he's a sheriff

in Los Angeles.

|

There were times, however, when Gary and I encountered a bit

of conflict in our boyhood relationship. For example, one time

when Gary was about six years old, he clobbered me with a stick.

In pain, I tried to show him that he shouldn't do such things,

arguing that hitting me wasn't what Jesus wanted him to do. He

disagreed, saying to me robustly: "Do unto others what you

want to do unto them."

Well, Gary was in the ballpark, but didn't get it quite right.

In fact, Jesus said, "Do to others as you would have them

do to you" (6:31). Interestingly, there are quite a few

parallels in Jewish and other sources to this saying of Jesus,

though they're not quite the same. The most common Jewish rule

was given expression by Rabbi Hillel, who said, "What is

hateful to you, do not do to your neighbor, that is the whole

Torah, while the rest is commentary" (b. Sab. 31a).

From the other side of the world, Confucius once said, "What

you do not want done to yourself, do not do to others" (Analects 15:23).

(For these and other examples, see Darrell Bock, Luke,

Vol 1, [Baker, 1994] pp. 596-597.) But, you no doubt noticed,

these statements approach the issue from the negative: Don't

do to others what you don't want done to yourself. Jesus is unique

among moral teachers in the strength and clarity of the positive:

Do to others what you want done to yourself.

Now there's a trustworthy rule of thumb for human behavior.

When in doubt, do to others what you would like to have done

to you. If you and I would only follow this rule, we'd be home

free in the ethical and relational realm. If you and I would

do this, virtually every conflict in our families would evaporate.

Plus, we'd no longer waste energy in our lives hurting each other,

but we'd be able to focus even more on the ministry of the kingdom.

You'll notice that Jesus didn't qualify the "others" to

whom we are to do as we wish they'd do to us. He didn't say "Do

only to those you like what you'd like them to do to you." In

context, it's clear that He's including among the others those

we'd consider our enemies. "Treat even your enemies as you'd

like to be treated." Now that's a tall order!

I wonder what our lives would be like if we too seriously the

call to do to others as we'd like them to do to us. It would

be an interesting to try this for one week. Treat the checkout

clerk as you'd like to be treated. Treat the people in your office

as you'd like to be treated. Do to your spouse as you'd like

your spouse to do to you. And so forth, and so on. Why not give

it a try?

Motivation for Loving

Our Enemies

Part 7 in the series: A More Inconvenient Truth

Posted for Friday, March 9, 2007

I've been working my way through a passage in Luke 6 in which

Jesus teaches us to love our enemies. Today I want to focus on

our motivation for doing something that is both counter-intuitive

and counter-cultural. Why would we choose to love our enemies?

Jesus explains what should motivate us in the following passage:

But love your enemies, do good, and lend, expecting nothing

in return. Your reward will be great, and you will be children

of the Most High; for he is kind to the ungrateful and wicked.

Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful (6:35-36).

My son Nathan and I enjoying each other many years ago. Even as human

fathers delight in their children, so our Heavenly Father delights in us.

|

Why would we be inclined to love our enemies? First, we

do so in anticipation of a great reward. And what is this?

Well, it may be, in part, the reward that comes in the end,

where our lives are judged by God. But this isn't the all of

it, or even the main part of it. The reward we receive

when we do what honors God is the knowledge of God's delight

in our obedience. Our reward is the "Well done, good

and faithful servant" that echoes in our souls through

the voice of the Spirit. Our reward is knowing that we are

living as faithful children of the Most High God, to Him be

all the glory!

There have been times in my life when I have tried to do what

Jesus demands in this passage, loving and doing good to those

who have mistreated me. In some instances I have seen people's

hearts change, and this has been wonderful. But there have been

many other times when my best efforts have not born the relational

fruit I had desired. To this day I feel pain over certain relationships

in which I did my very best to love even when I got dumped on

in return. I still yearn for reconciliation that might never

come this side of heaven. And, honestly, I have sometimes felt

like a naïve fool when I've opened my soul to people who

used the occasion to trample on me still further. But I have

taken comfort in the knowledge that God knows my heart and is

pleased with me. And, in the end, nothing matters more than this.

I long for my life to give God pleasure, even as I seek to glorify

and enjoy Him forever.

So, first of all, we are motivated to love our enemies by the

assurance that our actions glorify God. Second, we are motivated

to love our enemies because of the relationship we already have

with God as His beloved children. You see, the more we live

in this relationship, the more we will seek to be like God, and

the more we will in fact become like God. We will be kind to

the ungrateful and the wicked because God "is kind to the

ungrateful and the wicked" (6:35). And we will be merciful

because our Heavenly "Father is merciful" (6:36).

After all, it is only by God's mercy that we have been saved

from the kingdom of darkness into His kingdom of light. Our experience

of divine mercy translates into our being willing and able to

offer mercy to others. God's mercy poured out into our hearts

becomes channeled to others through our imitation of our heavenly

Father as His beloved children. So God's own mercy sets the standard

for us. And God's own mercy alive within us enables us to be

merciful.

Love Your Enemies:

Political Implications (Section A)

Part 8 in the series: A More Inconvenient Truth

Posted for Tuesday, March 13, 2007

So far in this series on loving your enemies I've focused on

the personal implications, what you and I should do as individuals

if we're going to put the imperative of Jesus into practice.

So far I have not dealt with the broader theological, ethical,

and political ramifications of the call of Jesus. I today's post

I want to offer a few thoughts in this direction.

Soldiers in Iraq receiving communion

|

To put things simply, since Jesus said we should love our

enemies, is it ever right for a Christian to use physical force

to restrain or even to kill an enemy? For example, is

it ever right for a Christian to serve in law enforcement or

in the military when the use of force would be required? Would

it ever be right for a national leader who is a Christian to

send our troops into battle, or to vote to approve or fund

a war?

There are Christians who answer these questions in the negative.

They believe that the call to love our enemies precludes all

uses of physical force against them. What sense does it make,

they ask, to say that I love my enemy when I might kill my enemy

in battle? And how could a Christian who is committed to obeying

Jesus ever support the use of military force against a national

enemy?

When I was in graduate school, I worshiped in a Mennonite house

church. Mennonites take the command of Jesus to love one's enemies

quite literally and foundationally. Most Mennonites are, therefore,

pacifists, who believe that Christians should not use violence

for self-defense, either personally or nationally. In the early

1980s, all of my Mennonite friends were strongly opposed to America's

possession of nuclear weapons. Many advocated immediate, unilateral

nuclear disarmament. At times they were arrested on charges of

civil disobedience in protests against the policies of the Reagan

administration.

I deeply respected the convictions of my Mennonite brothers

and sisters. I admired the extent to which they sought to take

Jesus seriously in every walk of life. I was challenged by their

moral arguments, which were carefully nuanced and based solidly

upon Scripture. I was inspired by their willingness to put their

convictions on the line and to suffer for them. Nevertheless,

I did not join them in their pacifism for three main reasons.

First, I don't think we can easily translate Jesus's teachings

for His disciples into national politics. Now let me say that

I'm not one who endorses what is sometimes called the "two

kingdoms" approach: where the kingdom of God and human kingdoms

are completely distinct, with completely distinct values and

purposes. Yet, at the same time, I believe that moving from the

teachings of Jesus to national policies is not a one-step or

even a very obvious process. Indeed, it requires dozens of exegetical,

theological, and philosophical steps, steps upon which wise Christians

often disagree. So, just because Jesus said that I should love

my enemies, this doesn't necessarily mean that the United States

should never use military force against a national enemy. It

might mean that, of course, but it might not.

Second, I didn't agree with my pacifist friends because they

seemed to accentuate certain parts of Scripture while minimizing

or neglecting others. "Love your enemies" and "Thou

shalt not kill" were given lots of weight, while biblical

teaching that God had given civil authorities the sword to punish

the wrongdoer was played down (see Romans 13:1-7). Scripture

itself, as far as I could discern, includes an inescapable tension

over the issues that pacifists resolve in one particular way.

(Of course, on the other side, there are Christians who play

up the "sword" text while neglecting the call to love

one's enemies. These folk seem to me to be just as lopsided in

their theology as pacifists.)

Third, I came to believe that the question of how we love our

enemies is, in practice, much more complicated than it might

at first appear to be. If an enemy were to attack me personally

and individually, I can see where the teaching of Jesus would

call me to non-retaliation. But if my enemy were to attack my

neighbor, then I'd be caught on the horns of a dilemma. After

all, I'm supposed to love my neighbor as well as my enemy. Love

for my neighbor would impel me to defend him or her against an

attack, even if that required me to use physical force to stop

my enemy. So we might find ourselves in a position where love

of enemies and love of neighbor appear to demand opposite actions.

In tomorrow's post I'll follow up with a hypothetical and a

real-life example of what I'm talking about in theory today.

Love Your Enemies:

Political Implications (Section B)

Part 9 in the series: A More Inconvenient Truth

Posted for Tuesday, March 13, 2007

Yesterday I began to explain why, though Jesus calls us to love

our enemies, I am not a pacifist. My reasons included:

1. It's not easy to translate Jesus's teachings for His disciples

into national policy.

2. Pacifism emphasizes certain biblical texts (like "Love

your enemies) over others (like Romans 13:1-7). It's the opposite

error of many Christians whose patriotic hawkishness seems

to be unchallenged by the call of Jesus.

3. Loving our enemies can be, in practice, quite difficult.

In fact, we might find ourselves in a situation where loving

our enemies and loving our neighbors required opposite actions.

Today I want to offer a couple of illustrations of #3, one hypothetical

and the other from real life.

A Hypothetical Example

Suppose you were a police officer, and you learned that a suicide

bomber was planning to detonate a bomb in the middle of a school

filled with children. You arrived at the school just in time

to see the bomber approaching the campus. Your call to "Stop" was

not heeded, and the bomber began to run toward the school. Your

choices would be clear: either use physical force to stop the

bomber or allow the bomber to fulfill the mission. In one case

a single person would be injured or killed by you. In the other

case, that person would surely be killed by himself while many

innocent children would be killed or wounded as well. If you

were the police officer, what would you do?

Hypotheticals like this one led me to reject the full-blown

pacifism of my Mennonite friends in graduate school. Yet I continued

to respect their effort to take the teaching of Jesus seriously

in a way that many Christians do not. Too may of us, I fear,

have minimized the relevance of Jesus, failing to take seriously

the widespread implications of the kingdom of God. Though there

may be a time when it's right to "bear the sword," this

does not mean that every instance of self-defense or military

action by our nation gets a free pass.

A Real Life Situation

Charl van Wyk encountered a real life situation not unlike my

hypothetical, only he is not a police office, but a full-time

Christian missionary who's involved in outreach in South Africa.

On July 25, 1993, Wyk was present in a worship service in St.

James church in Cape Town. There were about 1,000 people present.

All of a sudden the service was interrupted by intruders with

rifles. Grenades were exploding in the sanctuary and bullets

were flying.

At that moment Wyk pulled out the revolver he always carried

with him. Because the worshipers had fallen to the ground to

hide from the bullets, he had a clear view of the killers. He

fired two shots, but they didn't stop the attack. Then he ran

to the rear of the church and fired more shots, until he ran

out of ammunition. In the end, he wounded one of the killers

before the sped way in a car. Eleven worshipers were killed while

58 were injured. More would surely have been hurt of killed apart

from Wyk's actions.

In a recent interview with FrontPageMagazine.com,

Wyk was asked about the morality of his actions. Here's what

he said,

I firmly believe that the most Biblical action I could take

at that time was to protect the lives of my brothers and sisters

in Christ from the onslaught. In fact, if I did not try

to protect them when I had the opportunity to do so, I would

have broken the commands of Scripture. . . .

In Proverbs 25:26 we read: “A righteous man who falters

before the wicked is like a murky spring and a polluted well.” Certainly,

I would be faltering before the wicked if I chose to be unarmed

and unable to resist an assailant who threatened the lives

of God's people.

Paul wrote in a letter to Timothy, “But if anyone does

not provide for his own, and especially of those of his household,

he has denied the faith and is worse than an unbeliever.” (1

Timothy 5:8)

The person who ordered the attack on the St. James church, a

man named Letlapa Mphahlele, was later asked why he did it. His

answer:

This attack was an act of terrorism in the true sense

of the word . . . . what terrorism is all about. We did

it to instill fear in the Whites in South Africa.

Charl van Wyk on the left. On the right is

Letlapa Mphahlele, the commander of the

terrorists who ordered the attack.

|

Some time after the shooting, Charl van Wyk went to the jail

to meet the attacker whom he had shot. There he met Mphahlele,

who had ordered the attack. In time the men were reconciled as

part of the larger reconiliation effort in South Africa.

Wyk argues that Christians "have not only a right but also

a duty to protect the innocent and to look after those whom God

has entrusted to us." Thus he insists that his actions in

the St. James massacre were right.

Is Wyk correct? Should he have opened fire on those who sought

to kill innocent worshipers on that fateful Sunday? By doing

this, he saved many lives. But was it right? And, if so, how

can we know when this sort of response is defensible and when

it is not? Is there a time when a nation, even a nation with

Christian leaders, should act to defend its citizens or the citizens

of other nations?

I'm raising more questions here than I'm answering. I know that.

My intent is not to resolve the complicated issues associated

with Jesus's command to love our enemies. Rather, I hope to encourage

all of us to wrestle seriously with the teaching of Jesus and

what it means for our lives as individuals, as members of our

community and church, and as citizens of our country. One thing

I know for sure: easy answers won't satisfy here.

P.S. If you're looking for a serious discussion of the issues

I have raised here, I'd recommend War

and Christian Ethics: Classic and Contemporary Readings on the

Morality of War by Arthur F. Holmes. This book is not

easy reading, but it provides a diversity of well-argued Christian

perspectives. You might also be interested in Charl

van Wky's book, Shooting Back. I have not read it,

but I expect that Wyk offers a challenging case for self-defense.

Home

|