| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

Unintended Lessons from Ted Haggard

Note: It is not the purpose of this series to heap further

scorn on Ted Haggard, or in any other way to make

his life more miserable. Rather, I want to use what has

happened to him as an opportunity for learning some

valuable lessons. These are, to be sure, not something

Ted Haggard intended. But I expect that if others can

learn valuable lessons from his experience, this would

be something that even Ted Haggard himself could appreciate.

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2006 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com . Thank you.

How to Be Rightly Wrong: The Example of Ted Haggard

Posted for Tuesday, November 7, 2006

Eight months ago I wrote a post called "How to Be Rightly Wrong: The Example of Oprah." The context was the controversy over the book A Million Little Pieces by James Frey. When his purported autobiography was shown to be full of exaggeration, Oprah, who had promoted the book, initially defended it. But then, a couple of weeks later, she admitted her error on her television show. She said, plainly, "I was wrong."

In my blog post on Oprah's admission I wrote:

How refreshing! When is the last time you heard a public person – an elected official caught with his hand in the cookie jar, a CEO of a failed company, or even a pastor who committed some grievous offense – say, flat out, "I was wrong." Such people usually find ways to appear to be sorry, without admitting error. "Mistakes were made," is a familiar refrain. Or "I apologize for any confusion." Sometimes a leader will appear to admit error, "I take responsibility for what happened," while actually blaming others.

Well, now we've got another example of a public person, in this case a pastor who committed some grievous offense, who is "rightly wrong" because he has admitted his error without equivocation.

Ted Haggard's fall from power and prestige is well known since it's been all over the headlines. Last week at this time he was one of the leading evangelical pastors in America. Today he is defrocked and humiliated because of various transgressions, including sexual immorality and drug use (or at least purchase). It's hard to remember a steeper fall from power and prestige.

At first Haggard seemed to waffle about what he had done wrong. In a stunning display of Clintonesque doublespeak, Haggard said that he did not have a "sexual relationship" with the gay prostitute who had accused him, and that he had bought illegal drugs but didn't use them. But in record time Haggard went from prevarication to outright, blunt admission and apology. |

|

| |

Ted Haggard in much happier times. |

You may have read a line or two from the letter of admission Haggard sent to his congregation, since these have appeared in press stories everywhere. You can find the whole letter here (PDF only). I want to quote several passages from Haggard's letter. My point is not to hold him up for scorn, but rather as an example of somebody who has the courage to take responsibility for his sins:

I am so sorry. I am sorry for the disappointment, the betrayal, and the hurt. I am sorry for the horrible example I have set for you.

The last four days have been so difficult for me, my family and all of you, and I have further confused the situation with some of the things I've said during interviews with reporters who would catch me coming or going from my home. But I alone am responsible for the confusion caused by my inconsistent statements. The fact is, I am guilty of sexual immorality, and I take responsibility for the entire problem.

I am a deceiver and a liar. There is a part of my life that is so repulsive and dark that I’ve been warring against it all of my adult life. For extended periods of time, I would enjoy victory and rejoice in freedom. Then, from time to time, the dirt that I thought was gone would resurface, and I would find myself thinking thoughts and experiencing desires that were contrary to everything I believe and teach.

The accusations that have been leveled against me are not all true, but enough of them are true that I have been appropriately and lovingly removed from ministry.

I created this entire situation. The things that I did opened the door for additional allegations. But I am responsible; I alone need to be disciplined and corrected.

Please forgive me. I am so embarrassed and ashamed. I caused this and I have no excuse. I am a sinner. I have fallen. I desperately need to be forgiven and healed.

Please forgive my accuser. He is revealing the deception and sensuality that was in my life. Those sins, and others, need to be dealt with harshly. So, forgive him and, actually, thank God for him. I am trusting that his actions will make me, my wife and family, and ultimately all of you, stronger. He didn’t violate you; I did.

We will never return to a leadership role at New Life Church. In our hearts, we will always be members of this body. We love you as our family. I know this situation will put you to the test. I’m sorry I’ve created the test, but please rise to this challenge and demonstrate the incredible grace that is available to all of us.

Now this is being "rightly wrong." Haggard doesn't try to blame others. He doesn't lash out at the media. He doesn't even condemn his accuser for exaggeration.

I'll admit that when I first heard about Haggard's moral failures, I was angry and sad. Both emotions had to do primarily with the damage Haggard has done to the church of Jesus Christ, including but not limited to his own church. Now, after reading Haggard's letter of confession, I am still upset, but sadness has overtaken anger in my heart. My sorrow has been multiplied by reading the letter written by Ted Haggard's wife, Gayle (PDF only).

I am not suggesting, by the way, that Haggard's being "rightly wrong" means that he should be restored to leadership in his church. Forgiveness, which Haggard deserves as a brother in Christ, does not necessarily imply restoration of this kind. My point is simply that Haggard, though having messed up in a huge way, has shown his true character by admitting his error and taking full responsibility for it. In this he has set an example for all who would find themselves in a position like his, even in much smaller and less public indiscretions.

The Surprise of the National Association of Evangelicals

Posted for Wednesday, November 8, 2006

The National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) has been in the news recently for the sad reason that its former president was the now-disgraced Ted Haggard. If you have read new stories referencing the NAE, you may well think of it as a hyper-right-wing organization of Christian fundamentalists . . . at least this is how the NAE is often portrayed by the secular press.

In fact, however, the NAE reflects a much wider spectrum of theological, social, and political perspective than one might think. In June of 2005 I did an extended blog series on what was then a new statement of the NAE. The statement was called "For the Health of the Nation: An Evangelical Call to Civic Responsibility." (Click here for a PDF version of the 12-page statment.) In my blog series I commended this statement for its theological wisdom and for how this wisdom was worked out in practical ways.

Certain elements of the statement are what one might expect, such as opposition to abortion or same-sex "marriage." Both other elements might surprise you. Here are several unexpected excerpts:

God identifies with the poor (Ps. 146:5-9), and says that those who “are kind to the poor lend to the Lord” (Prov. 19:17), while those who oppress the poor “show contempt for their Maker” (Prov. 14:31). Jesus said that those who do not care for the needy and the imprisoned will depart eternally from the living God (Matt. 25:31-46). The vulnerable may include not only the poor, but women, children, the aged, persons with disabilities, immigrants, refugees, minorities, the persecuted, and prisoners. God measures societies by how they treat the people at the bottom.

Economic justice includes both the mitigation of suffering and also the restoration of wholeness. Wholeness includes full participation in the life of the community. Health care, nutrition, and education are important ingredients in helping people transcend the stigma andagonyof poverty and re-enter community.

We further believe that care for the vulnerable should extend beyond our national borders. American foreign policy and trade policies often have an impact on the poor. We should try to persuade our leaders to change patterns of trade that harm the poor and to make the reduction of global poverty a central concern of American foreign policy.

Human beings have responsibility for creation in a variety of ways. We urge Christians to shape their personal lives in creation-friendly ways: practicing effective recycling, conserving resources, and experiencing the joy of contact with nature. We urge government to encourage fuel efficiency, reduce pollution, encourage sustainable use of natural resources, and provide for the proper care of wildlife and their natural habitats.

Now you've got to admit this isn't what you'd expect from in a statement from the National Association of Evangelicals. There is much more wisdom in this statement, representing an effort at a truly and fully Christian engagement with the world.

So, as you think of the National Association of Evangelicals, I hope you'll consider downloading and reading their excellent statement on Christian civic engagement. It's well worth the time and effort.

Ted Haggard and Pastoral Pressure

Part 3 of the series: Unintended Lessons from Ted Haggard

Posted for Tuesday, November 14, 2006

I have been known to criticize the Los Angeles Times for its reporting, especially on matters of religion. But often the Times gets its religion stories right. Last Saturday was a fine example. Times staff writer K. Connie Kang wrote an article entitled "In One Week: Counsel, Soaring Hope, War Protest," in which she summarized a strange juxtaposition of events in the religious world, including the installation of Katharine Jefferts Schori as presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church USA and the vote of the National Council of Churches that called for an immediate phased withdrawal from Iraq. (It tells you something about the NCC when you realize the vote was 99% in favor of the motion.)

The bulk of Kang's story focused on the Ted Haggard affair. The point was not to increase Haggard's shame, but rather to reflect on the implications of his situation for the wider church. Several paragraphs struck me as worthy of reflection:

Experts say being a pastor today, especially of a prominent church, is more difficult than in the past because so much is expected of clergy.

"This is one of the greatest points of pain in the church, the expectations we attach to ministers," said the Rev. James P. Wind, president of the Alban Institute, a nonprofit ecumenical group that supports congregations and pastors.

"If you ask people what they want, they want a great preacher, a great administrator, great worship," he said in a telephone interview. "They want you to be available whenever they need you."

Given the fact that I am a pastor, you can see why these paragraphs grabbed my attention.

I did a bit of web-surfing to see if anyone else had made a similar observation about the implications of the Haggard affair. I found a quotation by H.B. London, Jr., of Focus on the Family. His statement came out in the Agape Press, providentially, just a week before Haggard's public disgrace:

H.B. London, Jr., is vice president of pastoral ministries with Focus on the Family. London says pastors often face enormous pressure and unrealistic expectations. "There's no way to know the pressure that most pastors are under just simply because the clock never stops running and the day never runs out, and unrealistic expectations seem to accompany the role of a servant pastor," says London. "In a sense, if you're a pastor to a congregation, you're everybody's private pastor, too. There's a constant need for you, especially in the smaller to middle-sized church." According to London, the unreasonable demands faced by members of the clergy can negatively affect their families. "I used to try to preach a lot about balance and how to have balance [but] I'm not sure that's even possible anymore," he concedes. "As pastors and as Christian leaders, we just have to make the most of what we can. And we've got to try to find those moments to get rest and to be refreshed and to be with our family and to minister effectively."

|

|

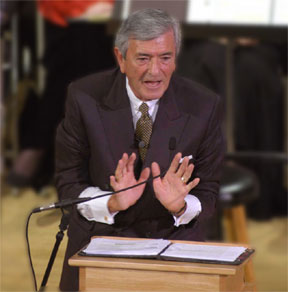

| |

H. B. London, Jr. |

Both James Wind and H.B. London agree that the expectations for pastors are problematic both for pastors and for the church. This suggests that the predicament is widespread among Christian churches, since Wind represents the theologically centrist-to-liberal Alban Institute, while London comes from the theologically conservative Focus on the Family.

I'm especially struck, and troubled, by London's sense that it's not even possible anymore for pastors to have balance in their lives. His conclusion, "As pastors and Christian leaders, we just have to make the most of what we can" is chilling to me, given that I am a pastor and a Christian leader who seeks to find balance in his work and his overall life.

Let me say that I can understand completely what Wind and London are saying, both from my observation of the church today and from my personal experience as a pastor. But I'm not yet willing to throw in the towel and simply try to make the most of what I can. I'm still idealistic enough, yes, even after 22 years of full-time work in the church, to believe that there are some things churches and pastors can do to make the problem of unrealistic expectations less burdensome for pastors and less frustrating for churches that feel as if their pastors aren't measuring up.

In my next post I'll offer some of my thoughts on how pastors and churches can work to overcome the problem of pressure placed upon pastors.

A Pastoral Privilege in the Midst of Pastoral Expectations

Part 4 of the series: Unintended Lessons from Ted Haggard

Posted for Wednesday, November 15, 2006

I had intended to begin today to offer some thoughts on how pastors and churches can work to overcome the problem of pressure placed upon pastors. But something happened today to interrupt my train of thought. I officiated at the graveside service for a member of my church, Glenn Wintermute (about whom I offered tribute in Monday's post). Yesterday we had the memorial service for Glenn, a time for a large group of friends and family to remember his life and celebrate his eternal life. Today was the graveside service, a much smaller and more informal gathering of close family and a couple of friends.

When I mentioned to a neighbor that I was doing these services, she said, "Oh my, that must be really hard!" Her comment got me thinking. No, I'd want to say to her, this isn't a particular hard part of my ministry. In fact, to tell the truth, it's one of the things I most value. I wouldn't want to say that I enjoy doing memorial services, since it is emotionally and spiritually taxing to be with grieving people. But I consider my role as pastor in times of loss to be a central part of my calling. It's something I find quite meaningful. In fact, it's a great privilege.

This might sound strange to you. I'm sure it would to my neighbor. But let me explain what I mean. Along the way there will be points of connection to the pastoral expectations and pressure issue. |

|

| |

Graveside services happen every day throughout the world. |

When a loved one dies, people come to a pastor, not only for help with a memorial service, but also for help with sorting out their feelings and their faith. They open up their hearts and their lives. When I meet with family members to plan a service, even if I've never met them before, they often share some of their deepest feelings with me. They laugh; they cry; they doubt; they hope. Thus I am welcomed into the inner sanctum of their lives. This is a huge privilege, one that continues to touch my heart after 22 years of "professional" ministry and dozens of memorial services.

Moreover, when I meet with people in this context, our conversation doesn't get mired in trivia, even though we're planning a memorial service. Rather, we talk about precious memories. We talk about family, friendship, and love. And we talk openly about God, faith, and heaven. In ordinary life, it sometimes takes a lot of relationship to get to the place where people openly share about such things, even with a pastor. But death has a way of helping us confront the most important things in life. So I get the privilege of talking with folks about the things that matter most of all.

These are the sorts of encounters that refuel my pastoral commitment. After all, I didn't enter the ordained ministry to deal with budgets, personnel policies, worship-style conflicts, and countless personal agendas for the church. Rather, I wanted to deal with people concerning the core issues of life. So, even though memorial services add a good chunk of busyness to my otherwise busy life, they allow me to do what I value most as a pastor. I get to talk with people about God. I get to help them find God's presence and comfort. People are almost never offended when this happens in the planning of a memorial service or during the service itself. They expect a pastor to do, well, pastoral things.

In this case, expectations for a pastor line up with what a pastor is supposed to do, at least in my opinion. When people come to me for a memorial service, they want me to point them to God. They want me to stand up in the service, read the Bible and share a few words of inspired truth. And that's exactly what I love to do. More importantly, that's what I'm called to do.

One of the other privileges associated with doing memorial services is the opportunity for me personally to think about what it means to live a good, full, meaningful life. I'm not talking only about faith, though that's certainly a key part of life lived to the max. I'm also talking about how a person lives each day. When I hear about how someone was consistently kind and giving–as in the case of Glenn Wintermute–I inevitably ask myself: Am I consistently kind and giving? If not, why not?

A few hours ago I watched as Glenn's casket was lowered into the ground. I thought about the fact that someday my body will be in such a casket. For me, this isn't a scary or morose thought, though I hope it won't happen for many years. But the fact that my life on this earth will come to an end is something I need to remember. It helps me make sure I'm living each day by faith in Christ. And it encourages me to renew my commitment to living each day to the fullest, making love my highest priority.

So, one of the unexpected privileges of being a pastor includes, not only being able to care for people in their time of loss, but also being reminded again and again of what really counts in life. This makes me want to focus my pastoral energies more and more on the important stuff, and somehow find a way to let the other stuff get less attention. But, this, in turn, raises once again the whole issues of expectations for a pastor. I'll have more to say about this tomorrow.

Pastoral Expectations and Pastoral Pressure: Further Reflections

Part 5 of the series: Unintended Lessons from Ted Haggard

Posted for Thursday, November 16, 2006

Two posts ago I quoted from two Christian leaders who were reflecting on the Ted Haggard debacle. One of these, James P. Wind, president of the ecumenical Alban Institute, connected this sad situation with the high expectations placed upon clergy today. "This is one of the greatest points of pain in the church, the expectations we attach to ministers," Wind said. H.B. London Jr., from the conservative Focus on the Family, expressed similar thoughts: "There's no way to know the pressure that most pastors are under just simply because the clock never stops running and the day never runs out, and unrealistic expectations seem to accompany the role of the servant pastor." London, who has been working with pastors for many years, added, "I used to try to preach a lot about balance and how to have balance [but] I'm not sure that's even possible anymore." Pastors, therefore, "just have to make the most of what we can."

As a pastor, when I read things like this I have a mix of feelings. On the one hand I feel relieved. I realize that when I feel the pressure and pain of the unquenchable expectations of my congregation, I'm not alone. I'm encouraged to know that my experience is like that of many if not most pastors because it suggests that I'm not the sole source of the problem. On the other hand, I feel discouraged, because if the problem of "unrealistic expectations" is as widespread as claimed by Wind and London, then it seems unlikely that I'll ever be able to solve it or escape from it. And if this is true, then at some point I have to decide whether I'm simply going to live with people's disappointment in me when I fail to meet their expectations, or decide to do something else in service to the Lord besides being a parish pastor.

But I am not quite as resigned as H.B. London seems to be, though I would concur with his recognition of the problem of pastoral pressure connected to expectations for pastors. One of the hardest things I have dealt with in my ministry–and continue to deal with–is people's unhappiness in me when I don't live up to their expectations. This is especially true when I believe that what they expect is unreasonable, or even impossible for an ordinary mortal. (Actually, in many places Jesus Himself disappointed people when He didn't live up to their expectations for Him!)

For example, most folks in my congregation expect me to preach biblically-solid, well-planned, spiritually-engaging sermons. I think this is a fair expectation, one I have for myself, in fact. But this expectation is inconsistent with what some people also want in terms of my pastoral availability. Some folks just don't realize how much time and emotional/spiritual effort this requires, especially if one is preaching to the same congregation (more or less) for many years in a row. A truly good sermon demands hours of study, reflection, prayer, organization, illustration gathering, writing, etc. etc. Dr. Lloyd Ogilvie, my mentor, former Chaplain of the U.S. Senate, one of the finest preachers in America, and the founder of the new Lloyd John Ogilvie Institute of Preaching at Fuller Theological Seminary, has said that a preacher needs one hour of preparation for every minute of preaching. He may well be right about this, though I think I can do well with a bit less time. But most people who appreciate a good sermon have no idea of how much time is required to prepare one. And not just quantity time, but quality time of quiet and prayer, time that isn't interrupted every other minute by phone calls, e-mails, and drop-in visitors. Thus folks tend to expect the preaching pastor to have much more time for other kinds of ministry than preaching pastors actually have if they're going to be any good at preaching.

I've said before that, though I recognize the problems associated with pastoral expectations and the pressure they produce, I'm not willing to give up trying to solve some of these problems. If a pastor is willing, and if a church (especially the leadership) is willing, then progress can be made on these issues, I believe. At least that has been my experience in the past, and it continues to be my hope.

I want to offer some suggestions both for pastors and for churches. I'll begin with pastors, though what I'm saying here would be worth reading for anybody who cares about pastors. I'll get to churches a bit later.

Suggestions for Pastors |

|

| |

Dr. Lloyd Ogilvie preaching up a storm

|

Suggestion #1: Acknowledge that you have a problem with congregational expectations.

When I was a younger pastor, I wanted to do everything right. And part of doing everything right included being in control, being able to handle every challenge. I thought that if I just worked hard enough and smart enough, if I prayed long enough and faithfully enough, that I'd be able to fulfill the expectations of my congregation. This idealistic course was leading me straight toward burnout, if not depression.

Today, I still want to do everything right. I still want to please every single member of my congregation. I still feel the impact of one critical word as if it were equal to a hundred positive words. But I am now able to admit to myself that I have a problem with congregational expectations. It's almost like I've needed to take the first step of a twelve-step program for pastors: I admitted I was powerless over congregational expectations–that my life had become unmanageable.

I've been helped in this process by the wisdom of more mature pastors, people like James Wind and H.B. London. Several years ago a retired pastor, one who is a highly-regarded national leader, said to me, "I don't know how you do it. People today want everything from a pastor. I don't think I could make it in today's church." His honesty helped me to say to myself, "Yes, this is really hard for me too. I feel the pressure of people's expectations all the time. And sometimes I feel completely overwhelmed."

Suggestion #2: Find a safe place where you can unpack your experiences and your feelings, a place to get at "your stuff."

Once you realize that you've got a problem with congregational expectations, you need a safe place to talk about it. Yes, by all means make this a matter of prayer, the ultimate "Safe Place." But I believe every pastor needs at least one more context in which complete honesty is possible. In most cases this will not be with members of your own church, by the way. You need a place where you can say, "Today I feel like quitting my job" without the other person worrying about how this might impact them.

Safe places might include: a covenant group of pastors; a relationship with a therapist; a prayer partnership with at least one other wise Christian, perhaps a more mature pastor; a relationship with a spiritual director. One advantage in seeing a trained counselor or spiritual director is that this person might help you discover the roots of some of your emotional reactions to other people's expectations. To cite a personal example, my father loved me very much, but didn't express his appreciation of me in words. This left a hole in my psyche. So when a person, especially someone who feels like my father, is disappointed in me because I didn't measure up to his expectations, this can pierce my soul. Knowing my vulnerability and where it comes from doesn't protect me against the pain of such things, but it does help me deal with this pain in a healthy manner, and not simply vow to work longer and harder to fulfill someone's unrealistic expectations.

I'm going to sign off for now. In my next post in this series I'll add a few other suggestions for pastors.

Pastoral Expectations and Pastoral Pressure:

Suggestions for Pastors (continued)

Part 6 of the series: Unintended Lessons from Ted Haggard

Posted for Monday, November 20, 2006

In my last post in this series, I began offering some suggestions for pastors who are wrestling the problem of pressure that comes from congregational expectations. My first two suggestions were:

Suggestion #1: Acknowledge that you have a problem with congregational expectations.

Suggestion #2: Find a safe place where you can unpack your experiences and your feelings, a place to get at "your stuff."

Today I'll put up a few more suggestions.

Suggestion #3: Talk about the issue of expectations with trusted lay leaders in your church.

I'll be the first to admit that I don’t always take my own advice here. There have been times when I have kept my feelings of discouragement and exhaustion to myself. But I have also known how good it feels and how helpful it can be to open up with trusted lay leaders in my church. In the best case scenario, at least some of these leaders will be on the official "board" of the church (elders, trustees, deacons, or whatever). And, to be sure, at some point the board will have to work with you on the whole question of expectations. But I'd encourage you to begin with a few (perhaps just one) lay leaders whose wisdom you trust, and who can also be counted on to keep confidence. When I have done this in the past, it has been quite helpful. Now I have sometimes had to hear hard things from the leaders with whom I have opened up, things about my own shortcomings. That's why I use the adjective "trusted" in describing the leaders with whom to be honest. You need to share with people you can trust.

By the way, I'm not suggesting that these lay leaders will constitute the "safe place" where you can open up completely. But they can offer perspective that will be helpful to you.

Suggestion #4: Make sure to keep your most important relationships strong and healthy.

When a pastor is feeling pressured, it's tempting for that pastor to work harder and longer. Often that means that he or she has less time for family and close friends. This generally makes matters worse, rather than better, because we derive strength, health, and wisdom from our primary relationships. On the positive side, there have been times when I've had a hard day at work and have come home to my family without much to offer. But then I started playing a game with my son, and before long I was laughing, enjoying myself in a truly restorative way. If you're married, then make doubly sure (triply sure? quadruply sure!) that your marriage is strong and healthy. In my life, there is nothing that has been more helpful to me in stressful times than the love and support of my wife. Of course this also protects me from the sorts of temptations that sometimes snare overworked and over-pressured pastors.

Suggestion #5: Be sure to take time away from church on a weekly basis, and extended time away from work on a regular basis.

Most pastors I know have a designated "day off." Often it's Monday, a day to recover from the demands of Sunday. Most pastors I know try hard to protect this day, though quite a few end up working a good part of it. Now when real emergencies come along a pastor needs to interrupt a day off. Last week, for example, I spent a good chunk of my Monday doing a memorial service. That was absolutely the right thing for me to do. But too often we pastors let our work flow into the day that serves as our personal Sabbath, and this isn't healthy or right. (A couple of years ago I even stopped looking at e-mail on my day off. It felt strange to do this, but it was essential to my getting the rest I needed.)

| In addition to a regular day off, pastors need to take time away from church for vacation and study. (Actually, all people need vacation time to maintain personal health.) The precise configuration of vacations will vary. But all of us need to get away from church for substantial chunks of time. I've found that if I take only a week away at a time, I really don't decompress adequately. Two weeks helps me to get a true break from work. Three weeks is ideal for a genuine, renewing vacation, but I'm not always able to get away for that long. |

|

| |

Activites like rafting down the Salmon River in Idaho keep me healthy and happy and ready to face the challenges of pastoral life. My family and I are in the second and third rows. |

I'm pleased to see that more and more churches have approved sabbatical policies for their pastors. My church was on the cutting edge of this, and I am personally grateful. I also think the leaders who came up with our policy exercised a lot of wisdom. I earn a three-month sabbatical for every seven years of work. So far I've taken two sabbaticals during my 15 and a half years at pastor of Irvine Presbyterian Church. I believe, to tell you the truth, that these breaks have helped me to stay on for so many years. They've refreshed my soul, strengthened my mind, renewed my body, and enriched my family life. My sabbaticals have also given the church a break from me, which has been good for the congregation.

I have two more suggestions for pastors, but I'll save them for tomorrow's post.

Pastoral Expectations and Pastoral Pressure:

Suggestions for Pastors (Section C)

Part 7 of the series: Unintended Lessons from Ted Haggard

Posted for Tuesday, November 21, 2006

In recent posts I've been offering some suggestions for pastors who are struggling to deal with the diverse and often inconsistent expectations of their congregations. So far I've put up five:

Suggestion #1: Acknowledge that you have a problem with congregational expectations.

Suggestion #2: Find a safe place where you can unpack your experiences and your feelings, a place to get at "your stuff."

Suggestion #3: Talk about the issue of expectations with trusted lay leaders in your church.

Suggestion #4: Make sure to keep your most important relationships strong and healthy.

Suggestion #5: Be sure to take time away from church on a weekly basis, and extended time away from work on a regular basis.

Here are my last two suggestions for pastors:

Suggestion #6: Devote sufficient time and energy to spiritual disciplines.

I'm referring here to well known disciplines such as personal prayer and Bible study. But I'm including other disciplines such as individual retreats, journaling, silence, fasting, study, scriptural meditation, spiritual direction, etc. The purpose of the disciplines is to help us know God more deeply and truly. I can't imagine anything more important for a pastor. Yet I am aware, both from what I hear from pastors and from my own personal experience, of how easy it can be to neglect spiritual disciplines. This is especially true if one is feeling lots of pressure from work. I can't tell you how many times I've sat down in the morning to spend time in Bible meditation and prayer, only to start thinking about all I have to do that day. I'm often tempted to skip my time with God in order to jump into doing God's work. Bad idea! But very tempting.

If you're struggling in your spiritual disciplines, I would strongly urge you to find at least one other person with whom to share the struggle. It might be another pastor. Or maybe a small group. Or a spiritual director. Or . . . . I've found tremendous encouragement from the support and accountability that comes from sharing my spiritual life with others. |

|

| |

The classic "recent" book on spiritual disciplines, now almost 30 years old: Celebration of Discipline

by Richard J. Foster. |

Suggestion #7: Remember who's your Boss.

A man in my church runs one of the largest and most successful companies in the country. One of my associate pastors recently sought him out for wisdom about how be an effective leader in church. The man said something like this: "Effective leading in church? Impossible! Mostly you're working with volunteers, over whom you have no real authority. Plus, everybody in the church thinks they're your boss." There's a measure of truth in this, I'm afraid, though I've found that most people in my church are willing to accept my leadership, thanks be to God!

Nevertheless, there are times when people's expectations pound upon us, and when people of power in the church do act as if they are our bosses. I should say that I believe pastors need to be held accountable. In my Presbyterian system, I'm accountable to a variety of people in a variety of ways, and I think this is mostly a good thing (though sometimes it can be confusing to all, including me). But there have been times in my ministry when, for example, somebody wrote a letter to my board of elders criticizing me, and it seemed as if the elders agreed, even though I've felt convinced that I had done the right thing. In these times of discouragement I've had to remember whom I'm really serving . . . not my congregation, not even my elders, but my Lord. He is ultimately my Boss. Yes, I want my congregation to like me, to be sure. And I want my elders to approve of me. But my true Boss is the Lord. I serve at His pleasure and for His pleasure. In the end, I would do what I believe honors the Lord, even if it were to cost me my job.

Now of course a pastor could abuse what I've just said, taking this as license to be unaccountable. I think any wise pastor must listen to the counsel of church leaders. Not to do so would be arrogant and foolish. But if your are listening to your lay leaders, and if you are taking seriously the input from your congregation, and if you are getting counsel from colleagues outside of your church, then you must be free to serve the Lord for His sake and for His glory, even if you don't do what those in your church want you to do.

Too many pastors–and I would sometimes number myself among them–are working for the praise of people, not of God. Many of us entered the ministry in part because of the affirmation we received. This is fine to a point. But it can also turn us into affirmation addicts. And this, in turn, will keep us from pastoring with the kind of clarity and authority we need. If I'm afraid to confront people with God's truth for fear of offending them, then I can't really be their pastor-teacher. So, though it's not wrong to enjoy affirmation from our congregations, we pastors must never let this become more important to us than our desire to hear from the Lord, "Well done, good and faithful servant."

In my next post in this series I want to offer up some suggestions for churches on how they can help pastors deal with expectations and pressure. But this will have to wait for a few days, because in the next couple of days I'll focus on Thanksgiving.

Pastoral Expectations and Pastoral Pressure:

Thoughts for Churches

Part 8 of the series: Unintended Lessons from Ted Haggard

Posted for Monday, November 27, 2006

In my last three posts in this series (beginning here) I offered some unsolicited advice to pastors dealing with the pressures that come from congregational expectations. In this post I want to add a bit more unrequested counsel, this time for churches who want to help their pastors survive in a world of lofty expectations. I believe that if pastors and churches can work together on this issue, there is hope for a mutually-beneficial solution. So, here's what I would offer to churches (especially lay leaders in churches):

Suggestion #1: Acknowledge the problem of congregational expectations for your pastor.

Perhaps you might want to review the quotations that got me focused on the issue of expectations for pastors. As you may recall, James P. Wind, president of the Alban Institute, said that high expectations for pastors "is one of the greatest points of pain in the church. . . . If you ask people what they want, they want a great preach, a great administrator, great worship. They want you to be available whenever they need you." In a similar vein, H.B. London Jr. of Focus on the Family added,

There's no way to know the pressure that most pastors are under just simply because the clock never stops running and the day never runs out, and unrealistic expectations seem to accompany the role of a servant pastor. . . . In a sense, if you're a pastor to a congregation, you're everybody's private pastor, too. There's a constant need for you, especially in the smaller to middle-sized church. . . . I used to try to preach a lot about balance and how to have balance [but] I'm not sure that's even possible anymore. As pastors and as Christian leaders, we just have to make the most of what we can.

Of course maybe you feel that the expectations for your pastor are not unreasonable. And perhaps you're right. But given the widespread trend in churches today, I'd encourage you to look closely at the possibility that your pastor is struggling with the pressure that comes from high, diverse, and ultimately unrealistic expectations from your congregation.

Why is this acknowledgement important? Well, for one thing, it would be reassuring to your pastor. There have been some times during my ministry when an elder in my church has glimpsed some of the demands I live with all the time. This person has said something like, "Wow! You've got a tough job. People want you to be everything for them, don't they?" A simple comment like this has often been great encouragement to me. At least somebody understands!

Moreover, if the members of a congregation will acknowledge that they have unrealistic expectations for their pastor, and especially if this happens among lay leaders (elders or deacons), then there is potential for dealing with this problem before the pastor burns out, or leaves, or quits, or gets fired.

Suggestion #2: Talk openly with your pastor about congregational expectations and how they might impact his or her work and life.

This sort of open conversation doesn't often happen, in my experience, both in my own church and in the churches of my colleagues. Why not? Well, partly we pastors don’t to be perceived as whiners and complainers. Ideally, I should be able to go to my board of elders and say at times, "I'm feeling overwhelmed by the expectations folks have for me in this church." But my insecurity keeps me from doing this. I don't want my lay leaders to think I'm a wimp. Or, worse yet, to think I'm just a lousy pastor who can't do the job.

Lay people don't talk with their pastors about the problem of expectations partly because they're unaware of it. They rarely stand inside the pastor's shoes, so they don't know what he or she experiences. And if the pastor doesn't speak up, it's unlikely that they will know what's going on, unless they read things like I quoted earlier and begin to put two and two together.

Moreover, I've found that some lay people don't actually believe their expectations are unfair. Yes, they do expect excellent preaching, administration, and pastoral care. They want their pastor to be well-prepared for preaching, and they want him or her to be consistently available on short notice for the personal needs of the congregation. They think these are fair expectations, and that their pastor had better live up to them . . . or else. I don't know quite what to suggest if you are one of these people, other than that you sit down and have a open-hearted conversation with your pastor. Perhaps you'll find your heart softening a bit and your mind opening a bit to how unrealistic your demands may be.

| Part of what makes pastoring so challenging, at times so fun (yes, fun), and at times so overwhelming, is the diversity of gifts and talents required. For example, good preaching requires that one devote a substantial amount of time to study, that one have a well-trained intellect, and that one be skilled as a public speaker. Good pastoral care requires that one devote time to being with people, that one have a sensitive, empathetic heart, and that one be skilled as listener. Good administration requires that one devote time to dealing organizational issues, that one have a systematic mind, and that one be skilled both as a leader and as a facilitator of group process. You can see where I'm going with this. The ideal pastor would have to be strong in virtually everything: mind and heart; people skills and solitary study; well-organized and also empathetic, etc. etc. Yet reality falls short of this ideal. Those of us who are more inclined to study and solitude, and thus who are often better at preaching and visionary leadership, struggle with the social demands of pastoring. Those of us who are extroverts, who love being with people, generally find that disciplines of study and quiet prayer don't come easily. And so for and so on. |

|

| |

Yours truly along with my associate pastor Tim (red scarf) and one of our trusty lay partners, dressed up for a Vacation Bible School skit. Sometime we pastors created expectations for ourselves. Ten years ago Tim and I dressed up for a VBS teaching skit. It was such a hit among kinds and parents that it became something I simply must do each year. Of course I actually like dressing up and acting silly as a means of teaching God's Word. But I sometimes worry about my successor, who will no doubt inherit VBS expectations, and who may not be the "dress up like a pirate" sort of person.

|

If a pastor and a congregation (or lay leaders from a congregation) can talk openly about these things, then there is the possibility of discerning together what a church really needs from its pastor, and what the pastor really needs to be doing (and not doing!). In the ideal situation, all parties can work toward optimizing pastoral effectiveness, for the benefit of both pastor and church.

Tomorrow I'll finish up with a few more suggestions for churches.

Pastoral Expectations and Pastoral Pressure:

Thoughts for Churches (continued)

Part 9 of the series: Unintended Lessons from Ted Haggard

Posted for Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Yesterday I began to offer some suggestions for churches that want to help their pastors deal with the pressure of that comes from excessive congregational expectations. I suggested:

Suggestion #1: Acknowledge the problem of congregational expectations for your pastor.

Suggestion #2: Talk openly with your pastor about congregational expectations and how they might impact his or her work and life.

Today I want to add to this list.

Suggestion #3: Seek to establish clear expectations that both pastor and church have endorsed.

This may not be as easy as it sounds, but it's well worth the effort. If the pastor and the church (usually the church board) can agree upon what the pastor should be doing, then this will be invaluable to all concerns. The pastor will know where to focus his or her time and energy for maximum benefit to the church. If members of the congregation have expectations that are beyond what has been agreed upon, not only can the pastor explain this to interested parties, but so can members of the board. There have been many times during my fifteen-year ministry at Irvine Presbyterian when my elders have helped somebody understand what I am called to do and not called to do, thus protecting me from unfair criticism.

Of course it's always possible that the effort to establish clear, mutually-agreeable expectations will end in a stalemate. The pastor will want one thing; the church will want something else. In this case, it's most likely that the pastor should seek another position and the church should seek another pastor. Yet how much better to go through this process of change before the levels of frustration have gone through the roof.

I should add that establishing expectations endorsed both by the pastor and by the congregation (or leadership board) is not something that happens only once. Changes in the church and in the pastor's own sense of calling are inevitable, and therefore the conversation about expectations should happen every few years. In my experience, this discussion should happen every three years or so.

Suggestion #4: Make sure your expectations for your pastor are shaped primarily by Scripture.

| We get our expectations for pastors from all sorts of places: from past experience, from movies and television, from our own fertile imaginations. Such expectations may or may not be consistent with God's expectations for pastors, however, expectations that are to be found in Scripture. In fact, the biblical job description for pastors often contradicts what people are apt to think. Consider the classic example. Most people in church expect that pastor to do the ministry. They are the recipients of this ministry, paying for it with their offerings. But Scripture reveals that pastors are in fact to equip the people so that they might do the ministry (see especially Ephesians 4:11-12). |

|

| |

Irvine Presbyterian Church when I arrived in 1991, before we built our sanctuary. |

Where I first started teaching this at Irvine Presbyterian Church fifteen years ago, some members were excited. They wanted to get involved in ministry, and were glad for some pastoral encouragement. Others weren't quite so pleased, however. I remember one day after a worship service getting chewed out by a long-term church member who said, "You're just trying to get out of your job by making us do it!" The fact that I was deriving my expectations from Scripture didn't seem to matter at the moment. (In time, I'm pleased to report, this man came to embrace the biblical picture of pastoring, and became one of my strongest supporters.)

Suggestion #5: Find ways to support and encourage your pastor.

I can tell you from lots of personal experience that it feels great when members of my church reach out to me. They've done this is many, many ways, including: notes of gratitude; thank you cards; special gifts for me and my family; spoken words of appreciation; offers of tangible help (like free babysitting when my kids were little); etc. For a number of years my church participated in the nationwide Pastor Appreciation Month. All of this has meant a great deal to me personally and to my pastoral colleagues at Irvine Presbyterian Church.

Tomorrow I'll finish offering my suggestions for churches.

Pastoral Expectations and Pastoral Pressure:

Thoughts for Churches (Section C)

Part 10 of the series: Unintended Lessons from Ted Haggard

Posted for Wednesday, November 29, 2006

Yesterday I added to my list of suggestions for churches that want to help pastors deal with the pressures associated with congregational expectations. So far I've got:

Suggestion #1: Acknowledge the problem of congregational expectations for your pastor.

Suggestion #2: Talk openly with your pastor about congregational expectations and how they might impact his or her work and life.

Suggestion #3: Seek to establish clear expectations that both pastor and church have endorsed.

Suggestion #4: Make sure your expectations for your pastor are shaped primarily by Scripture.

Suggestion #5: Find ways to support and encourage your pastor.

Here are my final suggestions:

Suggestion #6: Make sure your pastor has adequate time for rest, including a regular day off, yearly vacation, and even a sabbatical.

My church has been very supportive in making sure I have a regular day off and that I take it most of the time. I have sufficient vacation to get away from the job for enough time to be refreshed. I also earn a 12-week sabbatical every seven years. I've taken two so far, and these have been invaluable to me. I realize that offering a sabbatical to a pastor may sound like a daunting thing, especially for smaller churches. But if you want a long, fruitful relationship with your pastor, I'd urge you to find a way to do it. Some churches I know have a one-month sabbatical that comes more often; others have a longer-term sabbatical that comes less often. I've found 12 weeks to be a good length of time, long enough for deep refreshment and refinement of vision, but not too long. When I get back after three months off, people still remember my name.

7. Remember who's the Boss of your pastor and of your church.

My last suggestion for pastors was similar to this: Remember who's your Boss. I explained that I believe it's good for pastors to be accountable to other human beings, and dangerous when pastors are not in such relationships. Indeed, this is one clear lesson to be learned from Ted Haggard. If, years before his private life became so luridly public, he had been able to share his struggles with a couple other men who could actually have held him accountable, he might have been able to avoid making headlines, not to mention losing his pastorate and embarrassing his family.

Nevertheless, I think it's crucial for all conversations about pastoral roles and expectations to be framed by a genuine acknowledgement of the sovereignty of God. The church is God's church. Your church is God's church. Your pastor has been called by God and is ultimately accountable to Him. Sometimes we–and I included myself in this "we"– forget these things, or else we acknowledge them as theological truths but otherwise fail to live by them. Lay leaders in a church, especially if they have a long history of church leadership and give generously to the church, can sometimes forget that they are not the lords of the church. Christ is the only Lord of the church, and He doesn't share this position. Of course pastors are notorious for projecting their own agendas onto churches, turning them into vehicles for their own self-advancement.

So many sad and terrible things could be avoided if we would truly acknowledge that God is the "Boss" of the church and the pastor. This means that I, as a pastor, must subordinate my wishes and preferences to God's will. And so must the people of my church, including the lay leaders. I'm not suggesting that this is easy. I've had to submit my will for my church to God probably a thousand times, literally. No doubt I'll have to do it again, because I quickly forget just who is the Boss of my church.

How I wish we could all acknowledge that the only pastoral expectations that really matter in the end are God's expectations! What I want to be as a pastor, what my congregation wants me to be, what my elders want me to be . . . all of these are important, but only to a point. In the final analysis (read, Last Judgment), the only opinion that really counts is God's opinion. This means that I must continually strive to discern His will for my ministry. If my congregation can partner with me in this process of discernment, so much the better. |

|

| |

Michaelangelo's painting of the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel |

Conclusion

I'm quite sure Ted Haggard didn't intend to get people thinking about pastoring because of his notable moral lapse. But if many pastors and churches can be empowered to deal with the issue of pastoral expectations because of what happened to Ted Haggard, then this is a good thing, both for pastors and for churches.

Home

|