| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

The Da Vinci Opportunity, Section 5

How the Popularity of The Da Vinci Code Book

and Movie Can Be Helpful to Christians and Others

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2006 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com. Thank you.

Excursus: Newsweek on "The Mystery of Mary Magdalene" (Section A)

Part 40 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Thursday, May 25, 2006

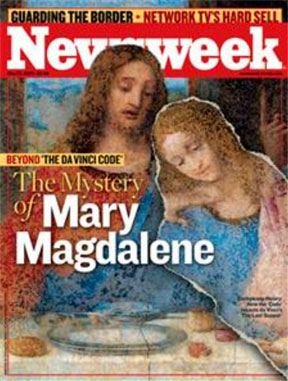

Catapulted forward by The Da Vinci Code juggernaut, Newsweek's cover story this week focuses on "The Mystery of Mary Magdalene." My first response in seeing this cover was mixed. For obvious reasons, I'm in favor of more attention being given in the press to biblical themes and persons. Yet recent history has shown that mainstream media reporting on such things is not always balanced or accurate. Writers often are unduly influenced by revisionist historians who have an axe to grind against orthodox Christianity. Or writers exaggerate in order to find a story where there is none, or where the truth is less spectacular than would merit a magazine cover.

Jonathan Darman reflects both of these tendencies – undue influence and exaggeration -- though not to such an extent that his article is substantially untrue or harmful to faith. In fact, Darman's piece contains more truth than empty conjecture, and his picture of Mary Magdalene throughout history has much to offer. Yet, as I would expect, there are problems along the way. In what follows I will quote from the Newsweek piece, and then offer my commentary. |

|

|

Newsweek: "An Inconvenient Woman"

What a strange title for this story! Of all the things one might say about Mary Magdalene, "inconvenient" would never have dawned on me. Why would Mary be inconvenient, unless she is the married Mary of The Da Vinci Code, or the anti-orthodox Mary of Gnosticism? This title suggests monkey business afoot, and alerts me to look for Darman's bias in favor of revisionist, pro-Gnostic accounts of Mary's significance. My guess is that he will project Mary's inconvenience into New Testament accounts where she wasn't preceived to be inconvenient at all.

The first paragraphs of the article, however, are a fairly straightforward summary of the biblical picture of Mary. Yet before long the article gets into the non-canonical Gospel of Mary.

Newsweek: Written by Christians some 90 years after Jesus' death, Mary's is a "Gnostic gospel"; the Gnostics, a significant force in the early years of Christianity, stressed salvation through study and self-knowledge rather than simply through faith.

Most scholars date the Gospel of Mary later than 120 A.D., though such an early date is theoretically possible. Darman chose the date that suits his purposes, no doubt. But more troubling here is the description of Gnosticism. Gnostic salvation did not come through "study and self-knowledge," but through supernatural revelation from various redeemer figures, who showed a few elites that they were really divine. Self-knowledge wasn't self-generated, but rather revealed. Darman's description makes Gnosticism appear far more postmodern than it really was. In Gnosticism you didn't get to discover your own truth. It came only be revelation.

Newsweek: To many feminists and theological liberals, the Gospel of Mary suggests that the Magdalene, the first witness to the Resurrection, was the "apostle to the apostles," a figure with equal (or even favored) status to the men around Jesus—a woman so threatening that the apostles suppressed her role, and those of other women, in a bid to build a patriarchal hierarchy in the early church.

First of all, it should be noted that the title "apostle to the apostles" is derived from ancient Christian tradition, orthodox tradition, I might add. (It is based on a line from the early third-century theologian Hippolytus.) Moreover, as the Newsweek article notes later on, Pope John Paul II himself used the "apostle to the apostles" description of Mary. So one should beware the implication that only feminists and liberals see Mary as a notable apostle. Darman is right, however, in observing that "many feminists and theological liberals" have seen Mary as threatening to the male apostles.

Newsweek: Mary was always an inconvenient woman. Although the Gospel authors can't avoid her—mentioning her 13 times in the New Testament—they offer few details of her life. This was perhaps no accident: women were considered untrustworthy in the Roman world, and the Gospels, eager to make new converts, probably did not wish to highlight the fact that a woman was a key witness to their story of the Resurrection—a story that was already difficult enough to explain.

This is a peculiar paragraph, one that reveals Darman's angle clearly. Why would the Gospel authors have wanted to avoid mentioning Mary or details about her life? Darman puts sinister motives in their minds that weren't there. Surely they could have skipped her altogether, easily, if they had wanted to. Many Gnostic gospels did this very thing, in fact. Mary doesn't show up in the Gospel of Judas or the Gospel of Truth. Did the Gnostic writers of these gospels find Mary inconvenient? Or were they simply focusing their attention elsewhere?

Mary is not singled out by the New Testament Gospel writers for exclusion. In fact, they tell us very little about any of the disciples of Jesus, besides Peter. Most of the male disciples are virtually ignored. We know almost nothing about Andrew, James, Philip, Bartholomew, Thomas, Thaddaeus, and Simon. Were these male disciples inconvenient? Hardly.

Darman is correct in saying that "women were considered untrustworthy in the Roman world." He's also right in noting that the Resurrection account with Mary in the forefront would have been a stumbling block in early Christian evangelism. In this way, Mary would have been inconvenient for the gospel writers. Yet Darman fails to draw the only appropriate conclusion: The gospel writers were so committed to telling the truth that they did not exclude Mary from the resurrection stories. How much neater and cleaner it would have been to replace Mary with Peter, for example. Yet the early church had a strong commitment to telling the truth about Mary, even when it was inconvenient.

Newsweek: Yet from the earliest hours of Christianity, there were other voices, too, those determined to present a fuller picture of the Magdalene. In several Gnostic Gospels, texts whose dissemination in the past 50 years has turned the study of Christian origins on its head, she is not the wallflower of the New Testament but rather a favored, perhaps favorite, follower of Christ.

This paragraph can only be called "Danbrownian" for its bias and exaggeration. Darman has abandoned object journalism and flung himself into the abyss of baseless speculation. Darman's insinuation that the stuff of the Gnostic gospels comes from "the earliest hours of Christianity" is, frankly, nonsense. Most Gnostic scholars believe that the stuff of the Gnostic gospels tells us much about second-century Gnosticism, but almost nothing about early Christianity. Those who claim otherwise have a miraculous ability to read between the lines.

Moreover, it's an exaggeration to say that the dissemination of the Gnostic Gospels "has turned the study of Christian origins on its head." The discovery of the Nag Hammadi Library has been a great help for those of us interested in the history of early Christianity. We now know much more about what the Gnostics believed than we did prior to the publication of the Nag Hammadi documents. One of the things we know, by the way, is that Gnosticism was quite diverse. Some Gnostics hailed Mary as the exemplary human revealer, while others gave Peter that role. But nothing has been turned upside down by the release of the Gnostic documents, except among scholars who have taken the side of Gnosticism in their opposition to Christian orthodoxy. They have turned things topsy-turvy, to be sure, in their affection for Gnosticism, or for what is left of Gnosticism after they take away from it everything offensive to their postmodern agendas.

In my next post I'll continue my review of "An Inconvenient Woman."

Excursus: Newsweek on "The Mystery of Mary Magdalene"

(Section B)

Part 41 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Friday, May 26, 2006

Yesterday I began my review of the latest Newsweek cover story, "The Mystery of Mary Magdalene." The actual article by Jonathan Darman is entitled, "An Inconvenient Woman." I will continue to do as I did yesterday, quoting a section of the Newsweek piece, and then adding my comments.

Why, then, did this woman, whom the New Testament tells us was Jesus' constant companion and whom the Gnostics claim was privileged above all others, disappear after the resurrection? If Mary were so important to Jesus, why is there no mention of her in Acts, or in the Epistles?

| This is a good question, though it goes beyond the evidence to say that Mary was "Jesus' constant companion." The most obvious answer is simple: Mary is not mentioned in the rest of the New Testament because we have very little information about any of Jesus's disciples, expect for Peter, and perhaps John. For example, Andrew, Bartholomew, Thomas, and Matthew show up only in one verse of the New Testament beyond the gospels (Acts 1:13). They also "disappear after the resurrection," if you will, but nobody suspects some sort of conspiracy to silence them. Mary, Jesus's mother, also makes an appearance in only one verse after the gospels (Acts 1:14). Jesus's close friends and followers, Mary (of Bethany) and Martha aren't even mentioned. Nor is Salome, one of the women who went to the empty tomb on Easter morning (Mark 16:1), though she does show up in the Gospel of Thomas. The New Testament writings focus mainly on the actions of Peter and Paul, with little attention paid to the other disciples. So, yes, Mary is not mentioned. But this should not be taken as evidence of some sort of plot against her. It has nothing to do with her being inconvenient. Rather, it is the result of our having very little information about the earliest Christians, other than a couple of the major players. |

|

| |

Piero di Cosimo,

"St. Mary Magdalene," 1490s

|

The noncanonical Gospels provide a troubling answer. In Gnostic texts, Mary is under constant attack, most often from Peter. "Tell Mary to leave us," he implores Jesus in the Gospel of Thomas, "for women are not worthy of life." Mary understands his threat. "I am afraid of Peter," she tells Jesus in the Gnostic Dialogue Pistis Sophia. "He threatens me and hates our race."

It is true that in some Gnostic gospels Mary is criticized by some of Jesus's other disciples. But to say that "Mary is under constant attack" is to stretch the available evidence far beyond the breaking point. It seems as if Jonathan Darman has been tutored by Sir Leigh Teabing. The facts about Mary in the Gnostic writings are these:

1. Mary appears relatively infrequently in Gnostic documents, overall. She shows up in the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Peter, the Dialogue of the Savior, the Apocalypse of James, the Sophia of Jesus Christ, the Pistis Sophia, the Gospel of Mary, and the Gospel of Philip. In only two of these writings, the Pistis Sophia and the Gospel of Mary, does she play a major role. Mary does not make an appearance at all in 85% of the Nag Hammadi documents (47 of 55). By way of contrast, Mary is mentioned in 100% of the New Testament gospels.

2. The theme of conflict between Mary and the other disciples is rarely found in the Gnostic gospels. To my knowledge, there are only four relevant passages in more than 500 pages of text:

In the Gospel of Thomas, Peter says Mary should leave them, "for women are not worthy of Life." To which Jesus responds that he will "lead her in order to make her male, so that she too may become a living spirit resembling you males" (section 114).

In the Gospel of Mary, Peter questions whether the Savior spoke openly with Mary, and not with him and the male disciples (9:5). Levi says he is "contending against the woman like the adversaries" (9:7). Earlier in this gospel, however, Peter asks Mary to tell him what Jesus revealed to her, apparently without resentment (5:5-7).

In the Gospel of Philip, the male disciples ask the Savior why he loves her more than them, but Mary isn't attacked by them in any way (section 64).

In the Pistis Sophia, Peter complains that Mary speaks too much, so Jesus gives him a chance to speak, and then praises him generously as "blessed beyond all men upon earth" (chapters 36-37). At a later point Mary says she is afraid of Peter"for he threatens me and he hates our race" (chapter 73).

3. Usually, when Mary shows up in the Gnostic gospels, she plays an insignificant role, or she is seen as a recipient of revelation alongside the male disciples, who are her colleagues in knowledge. In the Dialogue of the Savior, for example, Mary, Matthew, and Judas are in conversation together with the Lord. In the Sophia of Jesus Christ, Mary appears along with Matthew, Philip, Thomas, Bartholomew. In the Pistis Sophia, Mary is joined by Philip, Peter, Martha, John, Andrew, Matthew, Mary the mother of Jesus, James, and Thomas. Though Mary takes the lead role in the Pistis Sophia dialogue with Jesus and is praised by him in glowing terms, the others participate and are praised by Jesus as well (including Peter).

In light of the textual evidence, it is a huge exaggeration to say that "Mary is under constant attack, most often from Peter." The truth is that in rare instances Peter challenges Mary or expresses discomfort with her presence. Moreover, Peter is often upheld in the Gnostic documents as a true recipient of divine revelation or even the preferred human conduit of this revelation (see these Nag Hammadi documents: the Apocryphon of James, the Acts of Peter and the Twelve Apostles, the Apocalypse of Peter, and the Letter of Peter to Philip). So the whole idea that Mary is favored by all Gnostics and Peter only by the orthodox ignores the diversity within Gnosticism itself.

In my next post I'll wrap up my review of "An Inconvenient Woman."

Excursus: Newsweek on "The Mystery of Mary Magdalene" (Section C)

Part 42 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Tuesday, May 30, 2006

At the end of last week I began to review the Newsweek cover story on Mary Magdalene. Today I complete that review. The format is the same as before: I'll quote passages from the Newsweek article and then add my own comments.

Mary's description of the risen Christ [in the Gospel of John] —unrecognizable, untouchable—is of a piece with the portrait of resurrection in the Gnostic texts. But in the New Testament, the men describe Jesus as a physical being in front of them, a body that lives, walks and breathes.

Once again there is a trace of truth here, but mostly confusion. It's true that in John 20 Mary at first doesn't recognize the risen Christ, and that Jesus says to her, "Do not hold onto me" (v. 17). But after her initial confusion, Mary does in fact identify Jesus. He is not, therefore, "unrecognizable." Mary reports to the other disciples, "I have seen the Lord" (v. 18). And the fact that He tells her not to hold onto him surely implies that He is not "untouchable." Darman is misreading John 20 because, ironcially, he's reading it through Gnostic eyes.

It does seem likely, however, that Gnostics found Mary to be their inspiration because of this story in John 20. Since they denied the fleshly resurrection of Jesus (as well as His actual crucifixion, by the way), they twisted the "don’t hold onto me" to mean that Christ was non-physical. And Mary gets "secret" revelation from Jesus that she is supposed to deliver to the other disciples, a theme developed at length in several Gnostic texts. The Gospel of Luke adds that the male disciples didn't believe the women's testimony about Jesus (Luke 24:11), implying that this included Mary's witness as well. The New Testament gave some Gnostics all they needed to begin to fabricate stories about Mary the rejected revealer, though other Gnostics did not develop this theme.

Orthodox clerics worried that the Gnostic belief in resurrection as spiritual release would compromise their teaching that Christ physically suffered on the cross to atone for the sins of man.

This is thoroughly confused. In fact, Orthodox clerics worried about the fact that the Gnostics openly denied that Christ physically suffered on the cross. The problem wasn't some implication of resurrection. It was the open Gnostic denial of the real suffering of the real Christ. See, for example, the Apocalypse of Peter, section 81, where the genuine, non-physical Christ is laughing during the crucifixion because He's not really suffering. Gnostic belief in a non-physical resurrection was a simple reflection of their denial of the goodness of physical life.

It wasn't long after Jesus' death, however, that male church leaders took steps to subordinate women. "As the church submits to Christ," Paul wrote to the Ephesians, "so wives should submit to their husbands." Yet Paul's letters also contain references to female missionaries throughout the empire. Among these women was Junia, whom Paul calls "outstanding among the apostles," and admits was in Christ "before I was."

This paragraph rightly notes an apparent tension in the New Testament between passages that picture women as active in ministry and having authority in church (Acts 18:26; 21:9; Romans 16:1-7; Corinthians 11:4-10; Titus 2:3), and even over their husband's bodies (1 Corinthians 7:4), and passages that instruct women to be subordinate to men (Ephesians 5:22; 1 Timothy 2:11-12). This is not the time or place for me to jump into this deep pool of New Testament interpretation. For now, let me note that the inclusion of women in ministry in the early church is striking, especially given the strongly patriarchal culture of the first-century. Passages that call for female subordination, when read in the context of culture and the documents in which they are found, turn out to be far less objectionable than they might at first seem to modern ears. To put it more positively, the New Testament, from Jesus through the epistles, holds women in high esteem and recognizes that they are full partners in the ministry of God's kingdom. Jesus's enlisting of Mary as the first "evangelist" may well have been inconvenient in a sexist culture, but it was a sign of the new creation inaugurated by His genuine resurrection.

The French were particularly enamored with the Magdalene—so enamored that, naturally, they made her French.

Tradition holds that Mary Magdalene died in Aix-en-Provence in southern France. The pulpit of the cathedral in Aix commemorates the tradition of Mary washing the feet of Jesus with her hair, though this tradition is not taught in the New Testament gospels.

Indeed, for all its revolutionary claims, "The Da Vinci Code" is remarkably old-fashioned, making Mary important for her body more than her mind. In the movie, we see a stricken, shadowy Magdalene with swollen belly being spirited out of Jerusalem by a crowd of attendant men. But we never hear her voice.

Indeed. This is exactly the point I made earlier in The Da Vinci Opportunity. How ironic it is that the Mary of The Da Vinci Code is seen as an emblem of secular feminism!

Brown's mistake [in misunderstanding the kiss of Jesus and Mary in the Gospel of Philip] is understandable. Sex sells in our time, as it did in Gregory's, and probably Jesus', too. Mary remains a prisoner, a mistaken creature of sex. History may yet set her free. There are still undiscovered gospels sitting in unknown deserts or on unknown library shelves. Scholars say it is only a matter of time before some of them surface and upend our notions of Mary and Jesus once again. |

|

|

Above: The pulpit of the cathedral in Aix-en-Provence, with "Mary" washing the feet of Jesus.

Below: I doubt Mary went to the Ben and Jerry's in Aix.

|

|

If Dan Brown were a historian or a journalist, I'd disagree about his mistake being understandable. I'd say it was poor scholarship. Period. As a novelist he can make things up willy-nilly, if he wishes. (Of course if, as a novelist, he implies that his interpretations of ancient documents are accurate, then this put him in the historian camp.)

This last paragraph of "An Inconvenient Woman" is truly odd. Mary is not a prisoner or a "mistaken creature of sex" in the most accurate yet minimal description of her, the New Testament gospels. There, she is a faithful, courageous, and blessed follower of Jesus, the first one to share the good news of His resurrection. Sex never plays into the biblical story, except insofar as Jesus's having women followers and revealing Himself first to a woman on Easter are stunning symbols of the empowerment of women. Mary doesn't need history to set her free. She simply needs people, including journalists who write cover stories for Newsweek, to read the New Testament gospels and take them seriously.

Excursus: The Curious Anti-Catholic Perspective of The Da Vinci Code Book and Movie (Section A)

Part 43 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Wednesday, May 31, 2006

Today's post isn't about debunking The Da Vinci Code so much as analyzing a curious feature of both book and movie: its virulent yet evolving anti-Catholicism. I'll begin this conversation today and finish it in tomorrow's post.

The Malleable Robert Langdon

One of the most striking shifts between The Da Vinci Code novel and The Da Vinci Code movie is the perspective of Professor Robert Langdon on Christianity in general and the Roman Catholic Church in particular. In the novel, Langdon is no friend of either, though, as Leigh Teabing notes, Langdon has "a far softer heart for Rome than I do" (p. 235). This comment comes after Langdon explained the Catholic desire to suppress heretical documents on the basis of the "sincere belief in [the Church's] established view of Christ" (p. 235).

Yet the Robert Langdon of the novel agrees with Leigh Teabing's assertions about the church's mistreatment of Mary and its cover-up to defend its power (p. 254). And, in perhaps one of the most stunning anti-Catholic passages of the book, Robert Langdon muses on "the deceitful and violent history" of the Church (p. 124-125). By way of illustration, he remembers the "most blood-soaked publication in human history," the Malleus Maleficarum, or The Witches' Hammer. He believes this was published by the Catholic Church (which isn't true; the church condemned the book). On the basis of this book, according to Langdon, "During three hundred years of witch hunts, the Church burned at the stake an astounding five million women" (p. 125). These musings come to Langdon about a hundred pages before the entrance of Sir Leigh Teabing, the most vehement of anti-Catholic characters in both book and movie.

One of the clearest signs of the change in Langdon in the film comes in the presentation of the Malleus Maleficarum. Now this anti-Catholic slander comes, not from Langdon, but from Leigh Teabing. He, not Langdon, brings up the witch hunts as an example of the Church's persecution of women. Langdon's only contribution to the matter is to say: "Three centuries of witch hunts . . . fifty-thousand women are captured, burned alive at the stake." To which Teabing adds, "At least that, some say millions." |

|

| |

Robert Langdon in his youth. That guy has always

had a hankering for big secrets, hasn't he?

|

A curious switch, don't you think? Partly it seems to reflect an awareness by the screenwriter that the novel's "five million women" killed was utter historical nonsense. The movie's Langdon, who suggests 50,000, is much closer to historical truth. (Fifty-thousand women killed is still terrible, by the way. Most of the killing came from secular authorities, however, not the Church, though the Church was surely complicit in this violence.) So the film pictures Langdon as more balanced, less vehemently and exaggeratedly anti-Catholic than the obsessed Leigh Teabing.

The Council of Shadows

Yet even Teabing in The Da Vinci Code movie has information that exonerates the Vatican itself. When Sophie Neveu wonders if Teabing believes that the Vatican is killing people, he states, "No. No. No. Not the Vatican. And not Opus Dei, either. . . . An ancient group of despots [in] high ranking positions throughout the Church . . . [the] Council of Shadows." Later, at the end of a meeting of this council that appears in the movie but not the book, the leader of the Council reminds Bishop Aringarosa that they would be excommunicated by the Church if their activities were discovered.

Thus, in The Da Vinci Code novel, the Roman Catholic Church is based upon a lie, a lie known to the highest officers of the Church, perpetuated for the sake of power, and something for which the Vatican itself is willing to kill innocent people. In the film, the Church is still based upon a lie, but it seems that this lie is not as widely known by members of the Vatican, and that those who defend the lie even to the point of murder are a small group whose activities are not sanctioned by the Vatican itself.

Robert Langdon's changed perspective from book to film, combined with the film's addition of the Council of Shadows, moderates the anti-Catholicism of the movie to a certain degree. But, as I'll explain tomorrow, in some ways the movie is even more strident than the book in its denunciation of the Church.

Excursus: The Curious Anti-Catholic Perspective of The Da Vinci Code Book and Movie (Section B)

Part 44 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Thursday, June 1, 2006

Yesterday I began a two-part analysis of the anti-Catholicism of The Da Vinci Code. I showed how, in the film, an altered Robert Langdon and the addition of The Council of Shadows softened, to some degree, The Da Vinci Code's anti-Catholic perspective. But this is not the whole story, I'm sad to say.

The Terrible Church of Teabing

It would be wrong to conclude that the movie significantly improves the picture of the Roman Catholic Church. In fact, the charges against the Church made by Teabing in the film are, if anything, more extreme than those in the book. For example, the cinematic Teabing goes beyond the novelistic Teabing by claiming that Christians began a holy war against Roman pagans, when in fact it was the pagan Roman Empire that brutally persecuted Christians prior to Constantine's reign.

Moreover, notice the change in a crucial paragraph from book to movie. This comes late in the story, when Sir Leigh Teabing is trying to persuade Langdon and Nevue to join his Church-busting cause: |

|

| |

Ian McKellen as Sir Leigh Teabing |

Book version: "Shall the world be ignorant forever? Shall the Church be allowed to cement its lies into our history books for all eternity? Shall the Church be permitted to influence indefinitely with murder and extortion?" (p. 408-9)

Movie version: "For 2000 years the Church has rained oppression and atrocity on mankind, crushed passion and idea alike, all in the name of their walking God. Proof of Jesus's mortality can bring an end to that suffering, drive this Church of lies to its knees. . . The living heir must be revealed. Jesus must be shown for what He was. . . . The dark con exposed."

A few moments later, Teabing adds that the exposing of the dark con is "our hope of freedom."

So, The Da Vinci Code movie seems both to exonerate the Catholic Church (as well-intentioned but generally deceived) while at the same time damning it as in the novel (The Church is based on the greatest lie in human history). The Vatican itself is not responsible for murder. Rather, a secret Council of Shadows within the Church hierarchy bears this burden. Yet, according to Leigh Teabing, the Church is responsible for terrible "oppression and suffering," which can only be stopped by revealing the secret of Jesus's humanity and thus bring "this Church of lies to its knees." But the Teabing of the film seems almost insane because of his grail obsession, and the more balanced Robert Langdon does not echo Teabing's shrill accusations, even if he ultimately believes Teabing's grail legends.

So Teabing's extreme denunciation of the church is not presented as the gospel truth. The Da Vinci Code movie, though still plenty anti-Catholic, is somewhat more nuanced than the book, largely because of the new perspective of Robert Langdon, which balances the more extreme and ultimately shrill voice of Leigh Teabing.

Why is Dan Brown Anti-Catholic?

Many have wondered why Dan Brown decided to paint the Catholic Church with such ominous colors, even in a book of fiction. Because Brown himself hasn't had much to say about this, I don't think we can know for sure. But I find a paragraph of the novel, something not picked up in the movie, to be suggestive of what might be Brown's personal viewpoint. This paragraph comes in a dialogue between Langdon and Teabing, after Langdon asks why Catholic clergy would kill members of the Priory of Sion. Here's part of Teabing's response:

"Yes, the clergy in Rome are blessed with potent faith, and because of this, their beliefs can weather any storm, including documents that contradict everything they hold dear. But what about the rest of the world? What about those who are not blessed with absolute certainty? What about those who look at the cruelty in the world and say, where is God today? Those who look at Church scandals and ask, who are these men who claim to speak the truth about Christ and yet lie to cover up the sexual abuse of children by their own priests?" (p. 266)

I wonder if this is the source of Dan Brown's animus against the Catholic Church. No matter what he believes about Church history, Brown is clearly struck by the terrible truth of clerical molestation and the shocking deceptions of some Church leaders in response to this reality. Sadly, none of this is Danbrownian nonsense. It's one of the most horrifying scandals in Church history. I wouldn't be surprised if this helps to explain Brown's impassioned anti-Catholicism.

Opportunity #6: The Antiquity of Christian Belief in the Divinity of Jesus (Section A)

Part 45 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Friday, June 2, 2006

This series on The Da Vinci Opportunity has been structured around seven opportunities afforded by The Da Vinci Code juggernaut. For review, these are:

The Da Vinci Code's claim that the Gnostic gospels present a more accurate picture of Jesus gives us:

Opportunity #1. The opportunity to demonstrate the antiquity and reliability of the New Testament gospels, in contrast with the Gnostic gospels.

The Da Vinci Code's promotion of the Christ of the Gnostic gospels gives us:

Opportunity #2. The opportunity to present the engagingly human Jesus of the biblical gospels, in light of which the other-worldly Christ of the Gnostic gospels pales in comparison.

The Da Vinci Code's hailing of Gnostic Christianity gives us:

Opportunity #3. The opportunity to show how the orthodox Christian gospel is available and inclusive, in contrast to the esoteric, exclusive message of salvation in Gnosticism.

The Da Vinci Code's claims about Mary Magdalene and women in early Christianity give us:

Opportunity #4. The opportunity to explain how the portrait of Mary Magdalene in the New Testament, which does not include her marriage to Jesus, affirms both Mary and women in general, and suggests the full inclusion of women in Christian life.

The Da Vinci Code's claims about the formation of the Christian canon and the involvement of Constantine in this process give us:

Opportunity #5. The opportunity to show how the Christian Bible in fact came to be recognized, and why this supports confidence in Scripture.

The Da Vinci Code's claims about the lateness of the belief in the divinity of Jesus give us:

Opportunity #6. The opportunity to demonstrate the antiquity of Christian belief in the divinity and humanity of Jesus.

The Da Vinci Code's favoring of Gnosticism gives us:

Opportunity #7. The opportunity to showcase the compelling, creation-affirming, hopeful Christian "story" of salvation through Jesus, which stands brilliantly in contrast to the obscure, creation-denying, despairing "story" of Gnostic salvation.

So far I've covered the first five opportunities, along with several excursuses on relevant topics: Gnosticism, the marriage of Jesus, the Gospel of Judas, a review of the film, a critical review of Newsweek's article on Mary Magdalene. In the next few days I'll finish up this series by addressing the last two opportunities and by responding to a few e-mail questions I've received from my blog readers.

What The Da Vinci Code Claims About the Divinity of Christ

Before I get to Opportunity #6, I should explain what The Da Vinci Code claims about the divinity of Christ. This is one place, interestingly enough, where the book and movie diverge a bit.

In the The Da Vinci Code novel, the divinity of Jesus was an afterthought, something added to early Christianity almost three centuries after the death of Jesus. Here are some relevant citations from the novel: |

|

| FAQ: What does The Da Vinci Code claim about the divinity of Christ? |

|

"At this gathering [the Council of Nicaea in 325 A.D.]," Teabing said, "many aspects of Christianity were debated and voted upon—the date of Easter, the role of the bishops, the administration of sacraments, and, of course, the divinityof Jesus."

"I don't follow. His divinity?"

"My dear," Teabing declared, "until that moment in history, Jesus was viewed by His followers as a mortal prophet . . . a great and powerful man, but a man nonetheless. A mortal."

"Not the Son of God?"

"Right," Teabing said. "Jesus' establishment as 'the Son of God' was officially proposed and voted on by the Council of Nicaea."

"Hold on. You're saying Jesus' divinity was the result of a vote?"

"A relatively close vote at that," Teabing added. "Nonetheless, establishing Christ's divinity was critical to the further unification of the Roman empire and to the new Vatican power base. . . ." (p. 233)

"It was all about power," Teabing continued. "Christ as Messiah was critical to the functioning of Church and state. Many scholars claim that the early Church literally stole Jesus from His original followers, hijacking His human message, shrouding it in an impenetrable cloak of divinity, and using it to expand their own power. I've written several books on the topic." (p. 233)

"The twist is this," Teabing said, talking faster now. "Because Constantine upgraded Jesus' status almost four centuries after Jesus' death, . . . [Constantine needed to invent the Christian Bible]." (p. 234)

Unlike in the book, the film version of Robert Langdon doesn't let Teabing's allegations go unchallenged. Here's the relevant section from the film (which may be imperfect, given the limitations of my ears):

| |

Teabing: Until that moment in history [the time of the Council of Nicaea], Jesus was viewed by many of His followers as a mighty prophet, a great and powerful man, but a man at most, a mortal man.

Neveu: Not the Son of God?

Teabing: Not even his nephew twice removed! [MDR: Bad theology but a clever line.] |

|

|

Teabing (McKcellen) and Langdon (Hanks) argue in Teabing's study. |

Langdon: Constantine did not create Jesus's divinity. He simply sanctioned an already widely held idea.

Teabing: Semantics

Langdon: No. It's not semantics. You're, you're interpreting facts for your own conclusions.

Teabing: Facts, for many Christians: Jesus was mortal one day and divine the next.

Langdon: For some Christians His divinity was enhanced . . .

[An argument ensues. Finally Sophie Neveu interrupts.]

Neveu: How many have been murdered over these questions?

Teabing: As long as there has been one God, there has been killing in His name.

It seems as if, between the writing of the book and the filming of the movie, Robert Langdon did a bit of homework, perhaps even reading a few of The Da Vinci Code busting books and sharpening up his grasp of church history. But, as I'll explain later, Langdon's attempted defense of the deity of Christ isn't nearly strong enough. In my next post in this series I'll discuss what really happened at the Council of Nicaea, and how this impacted Christian understanding of Jesus and His deity.

Opportunity #6: The Antiquity of Christian Belief in the Divinity of Jesus (Section B)

Part 46 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Monday, June 5, 2006

According to The Da Vinci Code's guru, Sir Leigh Teabing, the divinity of Jesus was a fourth-century invention of the Roman emperor Constantine, who "deified" Jesus in order to expand his own imperial power. This happened, according to Teabing, at the council of Nicaea in 325 A.D., during which a vote was taken and the divinity of Jesus won by a small margin. Thus, according to the film version of Teabing, "Jesus was mortal one day, and divine the next."

What Really Happened at the Council of Nicaea?

Sometimes Sir Leigh's "facts" suggest that somebody has been spiking his Earl Grey. Yet in this case he gets some of the basics right. According to the church historian Eusebius of Caesarea, who wrote a treatise entitled The Life of Constantine, during Constantine's reign the Christian church and therefore the Roman Empire were being stirred up by a divisive theological dispute over the relationship between Christ and God. So Constantine summoned Christian bishops from throughout the Roman world to a gather in Nicaea (now Iznik, in northern Turkey). This gathering is known as the Council of Nicaea or the First Ecumenical (meaning "worldwide") Council. The bishops of the Council of Nicaea did indeed debate the nature of Christ and His divinity. And the winning side did indeed conclude that He was divine, sharing fully in God's own nature. |

|

| FAQ: What really happened at the Council of Nicaea? |

|

But Teabing gets many of the facts wrong. First, though the Nicene Council did indeed debate the nature of Christ, the losing side, led by Arius of Alexandria, did not believe that Jesus was merely human, simply "a mortal prophet" as Teabing says. Rather, Arius affirmed that Christ was more than human, but not completely divine in the same way that God the Father was divine. The Arian Christ was more of a demi-god, somewhere in between full deity and full humanity.

Second, the Council of Nicaea was not closely divided about the divinity of Christ, at least by the end of the proceedings. Almost all of the bishops at the gathering signed a statement that affirmed the full deity of Christ, who is "of the same substance" as God the Father (homoousios, in Greek). It is true, however, that Arianism didn't disappear at the Council of Nicaea. This doctrine, deemed heretical by orthodox Christians, continued to be popular for several decades.

Third, the Nicene Council did consider matters besides the definition of the divinity of Christ. Among these issues, the Council tried to get all Christians to celebrate Easter on the same day of the year (an effort that failed, by the way), and it approved some rules to guide the behavior of the bishops. There is no evidence for Teabing's claim that Constantine and the bishops determined which gospels should be in the Christian Bible. This question had been settled among orthodox Christians about a century earlier.

Gnostics and the Divinity of Jesus |

|

| |

An icon of the Constantine and the leading bishops from Nicaea, holding the first part of the Nicene Creed in Greek. |

One of the strangest aspects of The Da Vinci Code's pseudo-history is the notion that the Gnostics thought of Jesus as truly and only human, while the orthodox Christians, under the influence of Constantine, turned Him into a divine figure. In fact, the Gnostics had very little interest in the human Jesus, and many Gnostics distinguished clearly between the man Jesus and the true Christ (or Savior). In the Gnostic Apocalypse of Peter, for example, Peter has a vision of the Savior "glad and laughing" on the cross. Why is He so happy? Because He isn't being crucified. Rather, the poor body suffering on the cross is "his fleshly part, which is the substitute being put to shame, the one who came into being in his likeness." The Savior further explains to Peter: |

|

| FAQ: Did the Gnostics believe in a more human Christ? |

|

"Be strong, for you are the one to whom these mysteries have been given, to know them through revelation, that he whom they crucified is the first-born, and the home of demons, and the stony vessel in which they dwell, of Elohim, of the cross, which is under the Law. But he who stands near him is the living Savior, the first in him, whom they seized and released, who stands joyfully looking at those who did him violence, while they are divided among themselves."

If one believes The Da Vinci Code's version of history, then all Christians thought of Jesus as merely human until the Council of Nicaea. At that point, the orthodox began to think of Jesus as divine. The Gnostics, presumably, hung onto the older view of the human Jesus. In fact, however, Gnostics had no interest in the human Jesus, the man who was crucified. The One who brings saving revelation is the Christ or the Savior, who is divine but not human.

Recently there's been a lot of hoopla about the Gospel of Judas, the most recent of the Gnostic gospels to be discovered. In this document, written sometime in the second century, Jesus praises Judas and sets him apart for special revelation. Why? Here's what Jesus says when comparing Judas to the other disciples, "But you will exceed all of them. For you will sacrifice the man that clothes me" (section 56, emphasis added). Notice, the body of Jesus is not the real Jesus, or even a part of the real Jesus. Rather, it is "the man" that the real, non-physical Jesus wears like a garment. Judas, by arranging for the killing of the body of Jesus, is praised and held in high regard.

So, ironically, if Leigh Teabing (or Dan Brown) were truly looking for a human Jesus, Gnosticism would be absolutely the wrong place to look. Orthodox Christians, on the other hand, affirm the humanity as well as the divinity of Jesus.

But when did Christians start thinking that the man Jesus was in some way also divine? Was this a late addition to Christianity, as Teabing asserts? Or was it a much older part of Christian belief? I'll answer this question in tomorrow's post.

Opportunity #6: The Antiquity of Christian Belief in the Divinity of Jesus (Section C)

Part 47 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Tuesday, June 6, 2006

As I mentioned a couple of days ago, it seems as if Robert Langdon studied up on his history between the writing of The Da Vinci Code and the filming of the movie. In the novel, Langdon joins Leigh Teabing in the opinion that Constantine made up the divinity of Jesus to expand his imperial power (p. 233). But in the film, Langdon takes the other side:

Teabing: Until that moment in history [the time of the Council of Nicaea], Jesus was viewed by many of His followers as a mighty prophet, a great and powerful man, but a man at most, a mortal man.

Neveu: Not the Son of God?

Teabing: Not even his nephew twice removed! [MDR: Bad theology but a clever line.]

Langdon: Constantine did not create Jesus's divinity. He simply sanctioned an already widely held idea.

What Langdon says here isn't precisely true, because it wasn't Constantine who sanctioned the deity of Christ so much as the bishops who gathered at Constantine's initiative. Nevertheless, the main point is correct. What happened at the Council of Nicaea did in fact sanction an already widely held idea, one that Christians had believed for almost three centuries.

When Did the Followers of Jesus Start Believing that He Was Divine

I'm going to put up a surprisingly short answer to this question because I've already written on the subject in much greater depth. If you're looking for details, check out my series Was Jesus Divine? The Early Christian Understanding. In that series I show that the deity of Jesus shows up in the earliest Christian writings we have, the letters of the Apostle Paul. These letters, written between around two decades after the death of Jesus, clearly affirm that He is divine in some strong sense (see, for example, 1 Corinthians 8: 4-6 or Philippians 2:5-11). Moreover, the way Paul writes about the deity of Christ suggests that he did not make up this idea, but in fact got it from other Christians who came before him (see 1 Corinthians 16:22). This means that Christian belief in the divinity of Jesus goes back to the earliest years after His death and, I must add, His resurrection. |

|

| FAQ: When did the followers of Jesus start believing that He was divine? |

|

The resurrection of Jesus had everything to do with His being thought of as divine, though not in a simple syllogism. The earliest Christians did not argue as some Christian do today that the resurrection itself proves the deity of Christ. At first glance, the resurrection exonerated Jesus, showed that He had been victorious over death, and demonstrated to His followers that He had indeed been the Messiah, albeit in an unexpected sense. Yet, in Judaism, the Messiah was believed to be an inspired human figure, not a divine one. We must remember that Jews were passionately monotheistic. But as believers in Jesus reflected upon the meaning of His death and resurrection, and as they remembered things He did and said with new insight, they realized that He was far more than merely a divinely-inspired human being. In some way He was also God in the flesh. It may be that many people inferred the deity of Christ immediately upon realization of His resurrection, like Thomas in John 20:26-29. It may be that others came to this conclusion more slowly. Yet no matter the precise process and timeline, I believe that the Holy Spirit led the earliest Christians to realize that Jesus the man was also God incarnate.

This is not to say, however, that the first-century Christians had a well-articulated Trinitarian theology. The details of Christ's nature, though suggested in the New Testament, weren't clarified until the fourth and fifth centuries A.D. When, for example, Jesus says in the Gospel of John, "The Father and I are one" (John 10:30), this surely implies the homoousios language approved in the Council of Nicaea, but it's unlikely that either Jesus or John thought in such terms. All of the seeds needed for growing orthodox Christology were present in the first-century writings of the New Testament, but it took several centuries for these seeds to grow to maturity.

Of course there may have been some followers of Jesus who didn't, at least at first, recognize His deity. In a striking passage, Matthew's gospel ends with an appearance of the resurrected Jesus to his disciples. Notice what Matthew adds: "When they saw him, they worshiped him; but some doubted" (Matthew 28:17). Some of the disciples offered to Jesus that which they, as Jews, would only give to God . . . their worship. But others doubted! Some unnamed disciples weren't ready to recognize Jesus as divine and to worship Him. Yet, in time, the vast majority of Christians came to acknowledge the deity of Christ. This majority included the Gnostics, by the way, who believed that the Christ (distinct from Jesus the inconsequential man) was fully and only divine. |

|

| |

Some artistic images of Jesus, such as this statue from the cathedral in Monaco, emphasize the deity of Jesus.

|

The fact that Christian belief in the divinity of Jesus goes back to the earliest years of Christianity shows, once again, how The Da Vinci Code is based on creative fiction rather than reliable history. It also gives confidence to those of us who believe that Jesus is God. It would disconcerting, to say the least, if in fact a Roman emperor had made up the deity of Jesus three hundred years after His death! Of course the fact that the earliest Christians believed Jesus to be divine doesn't prove that He was (and is) in fact divine. Such personal faith goes beyond the conclusions of history. Yet Christian faith stands upon those conclusions as something reasonable, something based upon God's actual work in history.

Opportunity #7: The Compelling Christian "Story" (Section A)

Part 48 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Wednesday, June 7, 2006

Finally, after 47 posts spanning almost three months, we arrive at the last of the seven Da Vinci opportunities. (Could this be the longest blog series in the history of the blogosphere? And if so, is this a good thing? Or a bad thing?) I have put the last opportunity this way:

The Da Vinci Code's favoring of Gnosticism gives us:

The opportunity to showcase the compelling, creation-affirming, hopeful Christian "story" of salvation through Jesus, which stands brilliantly in contrast to the obscure, creation-denying, despairing "story" of Gnostic salvation.

In fact, I want to broaden my scope a bit and contrast the Christian "story" with, not only the Gnostic story, but also the theological "story" of The Da Vinci Code. By using the word "story" I'm not implying that some narrative is either true or false. It should come as no surprise to you that I find the Christian story to be true and the other stories to be fictional. Yet these are all stories. They all narrate the actions of God in the world. And they all help us to locate our place in the cosmos and find meaning in life.

The Gnostic Story

Although Gnosticism was a diverse movement, most Gnostics affirmed a basic story that helped them to understand who they were, what life was all about, and how they could find salvation.

The Gnostic story begins with God, a being so high and removed from this world that He can hardly be described. This God above all gods somehow manages to produce other gods, who produce other gods, filling the spirit world with lesser deities. Yet somewhere along the way one of the gods turns away from the highest God. In particular, this god decides to imitate the true God by creating something, much as the true God created the other deities. But the lesser god is unable to match the original divine effort, and instead creates something inferior, something ugly, something evil. What is this mistake created by the lesser god, sometimes called the "Demiurge?" It's the physical world and the people who live within it. Thus, unlike the biblical story of a good creation by the good God, the Gnostic story begins with creation as an unfortunate mistake.

Human beings are trapped within this evil world. But there is hope. Buried deep within each person – or, as some Gnostics believed, within a small number of special individuals – is a spark of divinity, a tiny remnant of the true God. People cannot discover this bit of deity on their own, however. That can only come from the outside. So the true God sends a Revealer who will let people – or the special people, at any rate – know who they really are. They are not their bodies. Rather, their true selves, the spiritual and divine part, are trapped within their bodies. Only knowledge – in Greek, gnosis -- of their true nature can set them free from the bondage of the material world and allow them to return to the true God.

In Christian Gnosticism, the Revealer is somehow associated with Christ (though less often with the man Jesus). The Revealer is frequently referred to as the Savior, rarely as Jesus. The true Revealer or Savior is not human, but is a divine being who is only incidentally associated with the human Jesus. The crucifixion of Jesus is irrelevant to salvation, because human beings don't need atonement for sin in order to be saved. Rather, they need the knowledge of their true divinity.

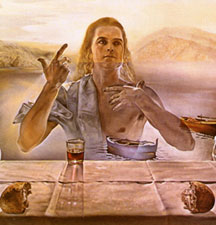

Thus the Gnostic story is fundamentally one of escape from this world into a pure, spiritual world. True Gnostics care little about what happens on earth. Their literature contains almost nothing about doing justice or caring for the poor. Rather, it focuses on how individual Gnostics can escape physicality and return to pure, other worldly spirituality. |

|

| |

In Salvador Dali's painting of the Last Supper, Jesus is a true Gnostic Revealer. You can see right through Him because He's not really human. |

Orthodox Christians in the second and their centuries sometimes accused Gnostics of libertinism, that is, of doing whatever they wished with their bodies, especially that which the orthodox considered to be sinful. It may well be that some Gnostics did engage in bodily sins, believing that the body had no eternal significance. But many Gnostics went in precisely the other direction, living Spartan and ascetic lives, denying human pleasures in the hope of becoming more spiritual.

So, this is the Gnostic story, the Gnostic view of life and its meaning. Tomorrow I'll outline the Christian story, and then talk how it is different from and, in my opinion, superior to the Gnostic story.

Opportunity #7: The Compelling Christian "Story" (Section B)

Part 49 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Thursday, June 8, 2006

Yesterday I outlined the Gnostic "story," that which explains who we are as people, why we're here, and where we're going. The Gnostic narrative, as you may recall, was based on the idea that this world is a mistake, a corrupt creation by an inferior god. The goal of life, therefore, is to "get out of Dodge," if you will, and find a way for the bit of divinity left within us to get back to the pure spiritual world.

The Christian Story

The Christian story begins from a completely different starting point. Based on the Jewish understanding of creation, the Christian narrative affirms that this world is fundamentally good, having been created by the only true, good God. Creation is not a mistake, but a wonderful part of God's work.

Similarly, human beings were created by the one, good God, and were in fact created in God's own image. God gave them substantial authority over His creation, and told them to take good care of it. Unfortunately, however, the first human beings weren't satisfied with their creaturely position. They rebelled against God and, in the process, messed up God's good creation. What remained after human sin entered the picture wasn't wholly bad. Creation, and indeed humanity, were fundamentally good, yet profoundly broken.

From the time that sin entered and corrupted God's world, God has been in the business of putting things back together again. He chose to do this by entering into relationship with the people of Israel, to whom He revealed His grace, righteousness, and holiness. Israel had the privilege of being God's special people for the sake of the world, the people through whom God would bring redemption and renewal to the world, and, indeed to the whole cosmos. |

|

| |

Michaelangelo's depiction in the Sistine Chapel of the expulsion of Adam and Even from paradise.

|

But Israel was unable to fulfill God's purposes in the world because the fundamental problem of sin wouldn't just go away. Even though God told His people how to live, they couldn't pull it off. So God promised that there would be a time when He would come to His people to set things aright.

God's way of fulfilling this promise was quite unexpected, however. Rather than coming in regal glory and awesome power, God came to earth as a baby. This child was raised in obscurity, having no particular privilege or power. But near His thirtieth year of life, Jesus began proclaiming the coming of God's reign on earth, and He began demonstrating the presence of that kingdom through miraculous deeds of power. Many Jews, and even a few Gentiles, were drawn to Jesus and His hopeful message of the kingdom of God. But others were put off by His unsettling proclamation and His sometimes scandalous behavior. What true holy man would mix it up with sinners as Jesus did?

The message of Jesus was profoundly personal. It was an invitation to a restored relationship with God by accepting God as king. But Jesus offered more than individual salvation. The kingdom of God would bring the renewal of this world, the restoration of creation to what God had intended it to be in the first place.

After a brief time of an itinerant ministry of preaching and healing, Jesus got into major trouble with the Jewish and Roman officials in Jerusalem. He was crucified on a Roman cross as a traitor to Rome and a pretender to the Jesus throne. This should have been the end of Jesus and His little renewal movement.

But within days of His crucifixion the followers of Jesus announced that He had been raised from the dead. God had vindicated Jesus, showing that His message was true, and that His vision for the future was accurate. Moreover, the death and resurrection of Jesus addressed the fundamental human problem: not a lack of knowledge of one's divinity, but eternal separation from God because of sin. Jesus took upon Himself the sin of the world, offering forgiveness and restoration with God. Through Jesus, that which went wrong when the first humans sinned was healed. In time, all creation would join in the wholeness wrought by Jesus.

Yet God did not instantly make all things new at the moment of Christ's resurrection. Rather, the resurrection was a window into the future, a sign of hope for what is to come. In Christ all things are made new, but that newness will only be experienced partially in this age. The Christian story looks ahead to the future when God restores and renews. Christians look forward to a new heaven and a new earth, with God Himself dwelling among us.

In the meanwhile, Christians accept the responsibility of proclaiming the good news of what God has done and is doing to save creation. We believe that we are to live out that good news in tangible ways, by fostering loving community, by forgiving our enemies, by caring for the poor, by seeking God's justice in the world today. Though we cannot usher in God's kingdom by our own efforts, we can reflect that kingdom in our individual lives and in our community, and extend His kingdom into the world through our words and deeds.

As you read this version of the Christian story, it might seem odd to you. It may even seem to be quite different from the version of the story you've heard in church. In my next post I want to reflect further upon the Christian story and how it impacts our lives.

Opportunity #7: The Compelling Christian "Story" (Section C)

Part 50 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Friday, June 9, 2006

Yesterday I outlined what I call the Christian "story," the overarching narrative concerning God and creation, that which gives ultimate meaning and purpose to this life, while instilling hope for the life to come.

This story would be familiar to anyone who has read a good bit of the Bible. Indeed, the story I summarized begins with the goodness of creation as revealed in the first two chapters of Scripture (Genesis 1 and 2), and ends with the new heaven and new earth seen in the last two chapters of Scripture (Revelation 21 and 22). Yet my version of the Christian story may have seemed to some people to be strangely focused. After all, doesn't the core Christian story have something to do with Christ dying for my sins? Isn't the basic point of Christianity believing in Jesus and going to heaven?

Let me be clear. I do believe that Christ died for our sins. I believe that because of His resurrection we can have confidence in Him and in the salvation He offers. I believe that one must be "born again" by trusting Jesus as Savior, and that that this experience leads to eternal life with God. I believe that the Christian story relates to each individual life, and includes personal salvation.

Yet what is often told as the Christian story – Christ died for my sins so I can go to heaven – is really only one small part of the whole story. It's a wonderful part, to be sure. But it's not the broader narrative of God's work in the world. Although I believe God knows and loves me personally, my salvation is one tiny element of His restoration and re-creation of all things through Christ.

| Perhaps an analogy will help here. Consider the "story" of World War II. One might tell the story of Viktor Frankl, an Austrian psychologist who was incarcerated by the Nazis in 1942, along with his family, because they were Jewish. During his three years in various prison camps, Frankl's wife, mother, and father were killed, along with countless friends and fellow sufferers. In 1945 Viktor Frankl was liberated by the United States Army. Shortly thereafter, he wrote one of the most influential books of the 20th century, called in English Man's Search for Meaning. In this book he argued that life has meaning even in the most dire of circumstances, and that this meaning gives strength and courage to human beings. |

|

| |

Viktor Frankl near the end of his life. |

What I have just summarized is a moving, true story of World War II. Yet it is only one small part of the larger story, one that begins with the rise of Adolf Hitler and involves, not just one man, but millions upon millions of human lives. It is one of the greatest tales in human history of the struggle between good and evil, and the ultimate victory of good over evil. Like the Christian story, the full story of World War II is complex, entangled, moving, and inspiring.

Even as Viktor Frankl's experience is a part of the larger story of World War II, so is my personal experience of salvation through Jesus Christ. Yet there is a much, much bigger story, one that encompasses the nations and, indeed, the whole cosmos. This is the mind-stretching, creation-affirming Christian story I narrated in my last post.

Ironically, sometimes we Christians sound an awful lot like Gnostics when we talk about our story. This is especially true when we speak of the future in terms of our spirits leaving this world and going to be with God. Don't get me wrong. I believe that we will indeed be with the Lord forever after we die. But the Christian story doesn't leave the material world behind. Rather, it celebrates the redemption and renewal of this world, including its people. Paul said that if "anyone is in Christ, there is a new creation" (2 Corinthians 5:17). He did not say, if anyone is in Christ, that person escapes from this fallen creation. Rather, the believer in Jesus participates in the new creation of heaven and earth, beginning at the moment of conversion and continuing forever. Moreover, the Christian accepts the divine calling to live in this world for God's purposes, proclaiming the good news of the Christian story, and living out this good news by joining a community of believers who, together, imitate the love and justice of God as they live hopefully in this world.

Postscript: Faith and Truth

Part 51 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Wednesday, June 14, 2006

In one of the most interesting sections of The Da Vinci Code novel, Robert Langdon and Sophie Neveu discuss the relationship of faith and truth. Langdon begins:

"There's an enormous difference between hypothetically discussing an alternate history of Christ, and . . ." He paused.

"And what?"

"And presenting to the world thousands of ancient documents as scientific evidence that the New Testament is false testimony."

"But you told me the New Testament is based on fabrications."

Langdon smiled. "Sophie, every faith in the world is based on fabrication. That is the true definition of faith – acceptance of that which we imagine to be true, that which we cannot prove. Every religion describes God through metaphor, allegory, and exaggeration, from the early Egyptians through modern Sunday school. Metaphors are a way to help our minds process the unprocessible. The problems arise when we begin to believe literally in our own metaphors." (pp. 341-342)

Then, a bit later, the dialogue continues, with Sophie adding,

"My friends who are devout Christians definitely believe that Christ literally walked on water, literally turned water into wine, and was born of a literal virgin birth."

"My point exactly," Langdon said. "Religious allegory has become a part of the fabric of reality. And living in that reality helps millions of people cope and be better people."

"But it appears their reality is false."

Langdon chuckled. "No more false than that of a mathematical cryptographer who believes in the imaginary number 'I' because it helps her break codes." (p. 342)

Robert Langdon's view of faith has a measure of truth in it. Faith includes accepting as true that which we cannot definitively prove. I cannot prove, for example, that Jesus died on the cross for my sins, though I certainly believe it. From a historical point of view it's highly likely that Jesus was crucified, but the "for my sins" part obviously goes beyond the historical facts, even though there are plenty of biblically-based arguments for the atoning significance of Jesus's death.

Here we see a good example of the nature of Christian faith. It is based on the facts, but goes beyond them. It is not believing fabrications, however. If it turned out that Jesus really didn't die on a cross, and that this had been made up by the early Christians for some crazy reason, then Christian faith would be in vain. No matter how much allegory or metaphor might be present in the crucifixion of Jesus, if it didn't actually happen, then we are still in our sins. |

|

| |

The dialogue I've cited in this post doesn't appear in the movie. A greatly revised version comes right near the end of the film, when Robert Langdom muses on the truthfulness of Christianity, and tells Sophie that the only thing that really matters "is what you believe."

|

I suppose some people might argue, as does Robert Langdon, that even this sort of error-based faith has value if it helps people live better lives. But this is not an orthodox Christian perspective. Nor is it a Jewish one, for that matter. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, people trust God in light of God's activity in the past and in response to His revelation. Faith is based on facts, even though it goes beyond them. Faith is not limited to what can be demonstrated by reason, though it is reasonable and can be defended with rational arguments.

Furthermore, Christian faith is not simply a matter of believing that which we cannot fully prove. It is a personal commitment of trust. It is saying, "I believe that Jesus died for my sins" and it is personally trusting Jesus to be my Savior. Because this act of trust requires more than human reason, God helps us to trust Him through the Holy Spirit, who enables us to confess Jesus as Lord (1 Corinthians 12:3).

Postscript: Did Christianity Pilfer from Paganism? (Section A)

Part 52 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Friday, June 16, 2006

According to The Da Vinci Code, Christianity as we know it has been strongly shaped by paganism. Here's a telling excerpt from the novel:

Teabing chuckled. "Constantine was a very good businessman. He could see that Christianity was on the rise, and he simply backed the winning horse. Historians still marvel at the brilliance with which Constantine converted the sun-worshipping pagans to Christianity. By fusing pagan symbols, dates, and rituals into the growing Christian tradition, he created a kind of hybrid religion that was acceptable to both parties."

"Transmogrification," Langdon said. "The vestiges of pagan religion in Christian symbology are undeniable. Egyptian sun disks became the halos of Catholic saints. Pictograms of Isis nursing her miraculously conceived son Horus became the blueprint for our modern images of the Virgin Mary nursing Baby Jesus. And virtually all the elements of the Catholic ritual – the miter, the altar, the doxology, and communion, the act of 'God eating' – were taken directly from earlier pagan mystery religions."

Teabing groaned. "Don't get a symbologist started on Christian icons. Nothing in Christianity is original. The pre-Christian God Mithras – called the Son of God and the Light of the World – was born on December 25, died, was buried in a rock tomb, and then resurrected in three days. By the way, December 25 is also the birthday of Osiris, Adonis, and Dionysus. The newborn Krishna was presented with gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Even Christianity's weekly holy day was stolen from the pagans."

"What do you mean?"

"Originally," Langdon said, "Christianity honored the Jewish Sabbath of Saturday, but Constantine shifted it to coincide with the pagan's veneration day of the sun." He paused, grinning, "To this day, most churchgoers attend services on Sunday morning with no idea that they are there on account of the pagan sun god's weekly tribute – Sun-day." (pp. 232-233)

Once again, there are grains of truth hidden in the chaff of The Da Vinci Code. Christians did swipe December 25th from the pagans, as I'll explain a little later. And the earliest Christians did honor Saturday as the holy day of the week before switching to Sunday. But, as we've seen before, Dan Brown let's his imagination run wild in his telling of history.

Take the Christian hallowing of Sunday, for example. It is truly striking that Christians, whose theological and liturgical roots were Jewish, stopped keeping the Sabbath and started sanctifying Sunday instead. It seems likely that the earliest Christians, who were all Jewish, continued to set aside the Sabbath as a day of rest and worship. But the switch from Saturday to Sunday began to happen early, way before Constantine's day. For example, John, the writer of Revelation, refers to being in the Spirit "on the Lord's day," or Sunday (Rev 1:10). By the second century, almost all Christians gathered on Sunday, not on Saturday.

If you're looking for data, let me quote from two early church fathers. The first comes from the Epistle of Barnabas, which was written early in the second century. The second comes from Justin Martyr, who wrote his First Apology in the middle of the second century.

Finally He saith to them; Your new moons and your Sabbaths I cannot away with. Ye see what is His meaning; it is not your present Sabbaths that are acceptable [unto Me], but the Sabbath which I have made, in the which, when I have set all things at rest, I will make the beginning of the eighth day which is the beginning of another world. Wherefore also we keep the eighth dayfor rejoicing, in the which also Jesus rose from the dead, and having been manifested ascended into the heavens. (Barnabas 15:8-9)

And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given,148 and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons. And they who are well to do, and willing, give what each thinks fit; and what is collected is deposited with the president, who succours the orphans and widows and those who, through sickness or any other cause, are in want, and those who are in bonds and the strangers sojourning among us, and in a word takes care of all who are in need. But Sunday is the day on which we all hold our common assembly, because it is the first day on which God, having wrought a change in the darkness and matter, made the world; and Jesus Christ our Saviour on the same day rose from the dead. For He was crucified on the day before that of Saturn (Saturday); and on the day after that of Saturn, which is the day of the Sun, having appeared to His apostles and disciples, He taught them these things, which we have submitted to you also for your consideration. (First Apology 67)

| Why did Christians change their holy day from Saturday to Sunday? Well, if this switch of day happened in the first and second centuries A.D., then Constantine wasn't involved. Of this we can be sure. Yet it did take something momentous to move Christian observance from Saturday to Sunday. But this wasn't a Roman emperor. It was the resurrection of Jesus. The prime motivation for Christians to honor Sunday was the fact that the resurrection of Jesus happened on the first day of the week. By gathering on the Sunday, Christians not only remembered the resurrection, but also looked forward to the new creation that Christ had begun by breaking the power of sin and death. |

|

| |

Ironically, my church added a Saturday evening service 13 years ago. We still celebrate the resurrection, however. |

Now it was certainly true that Christian recognition of Sunday was something that pagans would have found more palatable than a Saturday Sabbath. But the notion that the origin of Christian Sunday lies in paganism is historically nonsense.

There are some features of Christianity that do have pagan roots, however. I'll discuss these in future posts in the Da Vinci postscript.

|