| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

The Da Vinci Opportunity, Section 4

How the Popularity of The Da Vinci Code Book

and Movie Can Be Helpful to Christians and Others

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2006 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com. Thank you.

Opportunity #4: The Empowerment of Women in Orthodox Christianity (Section B)

Part 31 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Monday, May 15, 2006

| According to The Da Vinci Code, Mary Magdalene is special because she was Jesus's wife and the mother of His child. This, as I've shown in my recent excursus on the marriage of Jesus, must be understood as part of The Da Vinci Code's fictional artifice, and not part of the factual foundation upon which the story is based. The evidence for the marriage of Jesus to Mary is very slim, if not non-existent. (Even if Leonardo Da Vinci's "Last Supper" did intend to portray a special relationship between Jesus and Mary, which is unlikely according to many art historians, there's no reason whatsoever to believe that Da Vinci had any accurate historical information about Mary.) |

|

| |

A detail of Da Vinci's "Last Supper," showing Jesus and John (of Mary, according to The Da Vinci Code). |

The Da Vinci Code uses Mary Magdalene in her role as Jesus's wife as a symbol of "the sacred feminine and the goddess" (p. 238). Moreover, she is pictured as the one whom Jesus had intended to lead the church (p. 248). Thus He is said to be "the original feminist" (p. 248). But, according to The Da Vinci Code, Jesus's intentions and His primordial feminism were ruined by the Catholic Church, which obliterated the truth about Mary, turning her into a prostitute (p. 253-254), and squelching the sacred feminine. Only the revelation of Mary's true identity will set things aright.

There are tidbits of truth in this scenario, though these are easily swamped by the wave of make-believe. As we have seen, Jesus did give Mary a unique and honored role as the first person to announce the good news of His resurrection. In some ways He could be called "the original feminist," as we shall see. And the traditional portrayal of Mary as a prostitute, which began in the late 6th century, was based on a mistaken identification of her with the "sinner" who anoints Jesus in Luke 7:36-50. Moreover, Christian theology has always maintained that God, whose image is male and female (Genesis 1:27), transcends the categories of human gender. Thus worship of the goddess was excluded by the church, and sexual intercourse, though an aspect of God's creation, was not seen as the ultimate form of religious expression.

But the notion that orthodox Christianity is fundamentally anti-woman, and that the empowerment of women requires a married Mary and a sacred feminine misconstrues historical reality. In an earlier post I pointed out the irony of The Da Vinci Code's supposed feminism. Mary is special, not because she is an exemplary disciple of Jesus, but because she has fulfilled the traditional roles of wife and mother. Mary's chief value, in this scenario, is not in her full personhood, but rather in her having a useful uterus. It would seem to me that secular feminists should be up in arms in opposition to The Da Vinci Code for its stereotypical portrayal of feminine worth.

Though calling Jesus "the original feminist" could lead to erroneous implications, it's true that Jesus's treatment of women was exceptionally positive. He always related to women with the utmost respect. In His teachings, women were held up as exemplary people of faith (for example, Mark 12:41-44). A woman could even serve as a symbol for God (Luke 15:8-10). In the biblical gospels, Jesus never says anything like is found on His lips in the Gnostic Gospel of Thomas from Nag Hammadi,

Jesus said, "I myself shall lead [Mary] in order to make her male, so that she too may become a living spirit resembling you males. For every woman who will make herself male will enter the kingdom of heaven." (Thomas #114)

In the New Testament gospels, Jesus had close relationships with women, many of whom were His followers (Luke 8:2-3) and students (Luke 10:38-42). When the teachings and actions of Jesus with respect to women are evaluated in light of His culture, He stands out for His high regard and exemplary treatment of women. It's no wonder that many were included among His disciples, including Mary Magdalene.

Mary stands out among the followers of Jesus, not because she was His wife, but because He chose her to be the first witness to His resurrection. Though we cannot know exactly why Jesus gave Mary the role of the first evangelist, we do know what an astounding symbol this was of the empowerment of women. In a society where the testimony of women didn't have legal clout, Jesus chose a woman to be the first to bear witness to His victory over death. Talk about a symbol of respect!

Not long thereafter, the symbolic empowerment of women in Mary became actualized as the Holy Spirit was poured out on both men and women, so that both would be able to minister through the power of God (Acts 2:1-21). Thus, the biblical documents show women with a wide variety of ministerial roles within the earliest church, including: prophet (Acts 21:9, 1 Corinthians 11:4-5; 14:31), teacher (Acts 18:26; Titus 2:3), minister/deacon (Romans 16:1), house church leader (Romans 16:3-5), and apostle (Romans 16:7). Where the ministry of women is circumscribed in certain situations (1 Corinthians 14:34-35; 1 Timothy 2:11-15), this doesn't undo their empowerment by the Spirit or their call to active participation in Christian ministry. Moreover, though the early church continued to honor women in the traditional roles as wife and mother, they were endowed with unequaled respect and authority in their marriages and families (1 Corinthians 7:1-40). All of this explains why so many women, including women of significant wealth and influence, were attracted to early Christianity (for example, Acts 17:1-12)

I don't mean to suggest that women in the church have received the respect and opportunity they deserved. Cultural influences and human sinfulness have often led to the unfair treatment of women. The example of Jesus with women has been too easily forgotten, as has as the empowerment of women by the Spirit. Biblical injunctions concerning women in ministry have often been misunderstood or misapplied. But, for orthodox Christians, what we see in Jesus and read in Scripture continues to challenge, critique, and guide our behavior. Thus we seek to honor women, not only for the fertility of their bodies, but also for the fertility of their minds. Women are valued not only for their ability to give birth physically, but also for their ability to play a leading role in the spiritual rebirth of people. Thus Mary Magdalene serves as a moving example of how a woman can follow Jesus with exemplary faithfulness, and how she can be called by God to the ministry of the gospel.

Opportunity #5: How The New Testament Gospels Made It Into the Bible (Section A)

Part 32 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Tuesday, May 16, 2006

Sir Leigh Teabing isn't a big fan of the Christian Bible, to say the least. Here are some excerpts from The Da Vinci Code that lay out the Leigh Teabing/Dan Brown take on Scripture:

"The Bible is a product of man, my dear. Not of God. The Bible did not fall magically from the clouds. Man created it as a historical record of tumultuous times, and it has evolved through countless translations, additions, and revisions. History has never had a definitive version of the book." (p. 231)

|

|

| FAQ:What does The Da Vinci Code say about how the New Testament gospels made it into the Bible? |

|

"More than eighty gospels were considered for the New Testament, and yet only a relative few were chosen for inclusion – Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John among them."

"Who chose which gospels to include?" Sophie asked.

"Aha!" Teabing burst in with enthusiasm. "The fundamental irony of Christianity! The Bible, as we know it today, was collated by the pagan Roman emperor Constantine the Great." (p. 231)

"Because Constantine upgraded Jesus' status almost four centuries after Jesus' death, thousands of documents already existed chronicling His life as a mortal man. To rewrite the history books, Constantine knew he would need a bold stroke. From this sprang the most profound moment in Christian history." Teabing paused, eyeing Sophie. "Constantine commissioned and financed a new Bible, which omitted those gospels that spoke of Christ's human traits and embellished those gospels that made Him godlike. The earlier gospels were outlawed, gathered up, and burned." (p. 234)

So, according to The Da Vinci Code:

| |

• The Bible is a human document not inspired by God.

• More than eighty gospels were considered for inclusion in the Bible, but only four made it, the others were destroyed.

• The decision concerning which books to include in the Bible – the canon of Scripture – was made by the Roman emperor Constantine.

• Constantine published his new Bible, which included only those gospels that emphasized Jesus's divinity and minimized His humanity.

• Constantine did this, not out of theological concern, but in order to augment his own political power. |

|

| |

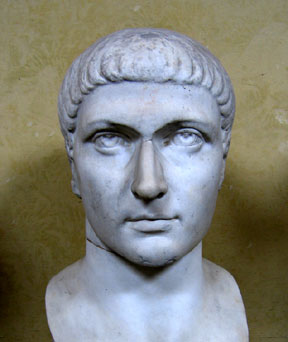

The head of Constantine in the Vatican Museum |

Almost everything claimed by The Da Vinci Code about the Bible is obviously wrong from a historical point of view, as I will soon show, though it adds to the intrigue of Dan Brown's fictional story. Ironically, the one statement of Leigh Teabing with which I agree is the first one of the bunch: "The Bible is a product of man, my dear." Christians affirm the human authorship of the Bible. We agree with Teabing that it "did not fall magically from the clouds." The books of the Bible were written by many human authors spanning many centuries. They are clearly a product of human effort.

Yet this does not mean, as Teabing alleges, that the Bible is "a product of man . . . . Not of God." Even as Christians affirm that Jesus is both fully human and fully God, so we believe that the Bible is both a human document and a divine document. The writers of Scripture, though completely human, were inspired by God to write as they did. Theologians continue to debate exactly how this happened and what it means for us. Some emphasize the human element, while others underscore the divine. But orthodox Christians of all theological stripes affirm that the Bible is a product both of man and of God.

There's no way to prove that the Bible is God's Word. I could show how the books of the Bible either imply or specifically claim God's role in their authorship. I could show how Jesus's use of the Old Testament and His authorization of the apostles suggest that the whole of Scripture is divinely inspired. I could explain how orthodox Christians throughout the centuries have honored the Bible as God's Word. And I could tell many personal stories about how God has used Scripture to reveal, save, heal, renew, and guide. But, in the end, all of this doesn't add up to conclusive proof of biblical inspiration, even if it points enthusiastically in this direction.

Yet if it were true that the books of the Christian Bible were collected by Constantine merely to enhance his political power, and if it were true that he eliminated from the canon many gospels that told the truth about Jesus, then it would be harder for people to have confidence in the divine nature of the Bible. Of course if God could use Balaam's ass to communicate His Word, then God could use a self-aggrandizing emperor to identify the genuinely inspired books of Scripture. But this scenario would be a hard pill to swallow for believers, and it would keep most non-believers from accepting the divine inspiration of the Bible as we have it.

In my next post I will begin to respond to the Teabing/Brown allegations concerning how Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John made it into the Bible. This response will be guided by two basic questions: 1) What was the role of Constantine in the formation of the Christian canon? 2) How was the canon of the Bible determined?

Opportunity #5: How The New Testament Gospels Made It Into the Bible (Section B)

Part 33 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Wednesday, May 17, 2006

According the The Da Vinci Code's revealer, Sir Leigh Teabing, the decision about which books to include in the Bible was made by the Roman emperor Constantine. He selected for the canon those documents that enhanced his political power. So, when it came to the gospels, Constantine chose from more than eighty known gospels the four that most emphasized Jesus's divinity and therefore augmented Roman imperial power. |

|

| FAQ: What was the role of Constantine in the formation of the New Testament? |

|

Here is Dan Brown at his creative best. As an imaginative novelist he gets an 'A.' If he were writing a paper for me in an early Christian history course, however, he'd get an 'F.' There's just about nothing true in this account of the origin of the Christian canon, other than the fact that Constantine was indeed a Roman emperor and the fact that Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were indeed included in the Christian Bible.

For example, as I explained earlier in this series, we have no reason to believe that there were ever eighty different gospels in existence. And even if there were, we have no reason to believe that anybody, ever, collected them and then decided which ones to include in the Bible. As we'll see a bit later, all of the extant early lists of inspired gospels include four and only four gospels, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. To be sure, the Gnostics would have had their collections too. But nobody was collecting gospels like baseball cards and then choosing their favorites for the Bible.

Constantine and the Bible

Moreover, there's no historical evidence to support the thesis that Constantine had anything to do with the formation of the Christian canon. One of the best sources of information about Constantine comes from the ancient historian Eusebius, who wrote The Life of Constantine. Eusebius was a supporter and admirer of Constantine, who wrote in part to celebrate the emperor's accomplishments. If Constantine had been involved in the choosing of canonical documents, surely Eusebius would have praised this as one more sign of the emperor's godliness. But Eusebius says no such thing. |

|

| |

The Arch of Constantine in Rome, next to the Coliseum (a bit of which shows on the right). This arch commemorates Constantine's victory that led to his becoming emperor. |

In fact, however, Constantine did write a letter to Eusebius in which the emperor instructed Eusebius to produce fifty, high-quality volumes of "the sacred Scriptures." This letter, which Eusebius includes in The Life of Constantine (4:36), assumes the existence of an authorized collection of sacred documents. Here's an excerpt from that letter:

I have thought it expedient to instruct your Prudence to order fifty copies of the sacred Scriptures, the provision and use of which you know to be most needful for the instruction of the Church, to be written on prepared parchment in a legible manner, and in a convenient, portable form, by professional transcribers thoroughly practiced in their art.

Although the fourth-century church continued to debate whether a couple of books should be included in the canon or not (Hebrews and Revelation, in particular), the scriptural authority of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John was well-established and never doubted by orthodox Christians during the time of Constantine's reign.

The emperor did play a significant role in the gathering of church leaders at Nicaea (a city in northern Turkey) in 325 A.D. But this council did not deliberate about the canon. Rather, it focused on how best to understand the divinity of Christ and a number of other issues, like the timing of the celebration of Easter, which Constantine himself seemed to think was the most important issue at the Nicene council.

If Constantine did not have anything to do with the selection of books for the Christian canon, and if the authoritative collection of New Testament books was mostly completed by the time Constantine became emperor (early 4th century A.D.), then how did those books come to be regarded so highly? I'll answer this question in my next post.

Opportunity #5: How The New Testament Gospels Made It Into the Bible (Section C)

Part 34 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Thursday, May 18, 2006

To story of how Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John made it into the Christian Bible is not nearly as intriguing as the one told by Dan Brown in The Da Vinci Code. And it's not nearly as simple, either. But, however fascinating the "Canon According to Constantine" story may be, it isn't what really happened. As I explained in my last post, there's no historical support for the thesis that Constantine had anything to do with the formation of the canon of Scripture.

There are also many parts of the true canon story that we don't know today because we don't have sufficient historical evidence. But the basic contours of this story can be charted, and this is what I propose to do in the rest of this post and in a couple to follow. I'll also cite various early sources that help us to determine the shape of the contours. Much of what I will relate here pertains to the whole of the New Testament, all 27 documents. But, for obvious reasons, I'll focus mostly on the gospels.

The Second Century Beginnings of the New Testament Canon

The fact that we have copies of the New Testament writings shows that early Christians valued them highly, or else they wouldn't have been preserved and re-copied. Moreover, early in the second century A.D., Christian writers quoted from the writings that would be included in the New Testament, much as they quoted from the Jewish Scriptures (the Old Testament). Among these special writings were four that told the story of Jesus, the documents that we call "gospels."

In the second half of the second century, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John became a foursome, to borrow a term from golf. We have evidence from various kinds of writings from this period, all of which points to the unique position given to these four writings:

Tatian's Diastessaron: Around 170 A.D., a Syrian church leader named Tatian took Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John and made one cumulative gospel, called the Diatessaron (from Greek, meaning, "one-through-four"). Tatian did not use any of the Gnostic gospels in his harmony.

The Muratorian Fragment: In 1740 Lodovico Antonio Muratori published a list of New Testament documents he had found in an eighth-century manuscript. Most scholars date the first writing of this list to around 170 A.D. Though the first part of the list is incomplete, it certainly included Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Here's how the existing list begins:

. . . at which nevertheless he was present, and so he placed [them in his narrative]. The third book of the Gospel is that according to Luke. Luke, the well-known physician, after the ascension of Christ, when Paul had taken with him as one zealous for the law composed it in his own name, according to [the general] belief. Yet he himself had not seen the Lord in the flesh; and therefore, as he was able to ascertain events, so indeed he begins to tell the story from the birth of John. The fourth of the Gospels is that of John, [one] of the disciples. . . . (emphasis added)

Irenaeus in Against Heresies: Writing around 180 A.D., Irenaeus, the bishop of Lyons, wrote a book refuting Gnostic and other Christian theologies he considered to be incorrect. In Against Heresies, Irenaeus acknowledges that the Gnostics wrote their own sacred works, but he recognizes four and only four gospels as authoritative. Here are a couple of excerpts from Against Heresies:

We have learned from none others the plan of our salvation, than from those through whom the Gospel has come down to us, which they did at one time proclaim in public, and, at a later period, by the will of God, handed down to us in the Scriptures, to be the ground and pillar of our faith. For it is unlawful to assert that they preached before they possessed "perfect knowledge," as some do even venture to say, boasting themselves as improvers of the apostles. For, after our Lord rose from the dead, [the apostles] were invested with power from on high when the Holy Spirit came down [upon them], were filled from all [His gifts], and had perfect knowledge: they departed to the ends of the earth, preaching the glad tidings of the good things [sent] from God to us, and proclaiming the peace of heaven to men, who indeed do all equally and individually possess the Gospel of God. Matthew also issued a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect, while Peter and Paul were preaching at Rome, and laying the foundations of the Church. After their departure, Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, did also hand down to us in writing what had been preached by Peter. Luke also, the companion of Paul, recorded in a book the Gospel preached by him. Afterwards, John, the disciple of the Lord, who also had leaned upon His breast, did himself publish a Gospel during his residence at Ephesus in Asia. (Against Heresies 3.1.1; emphasis added)

It is not possible that the Gospels can be either more or fewer in number than they are. For, since there are four zones of the world in which we live, and four principal winds, while the Church is scattered throughout all the world, and the "pillar and ground" of the Church is the Gospel and the spirit of life; it is fitting that she should have four pillars, breathing out immortality on every side, and vivifying men afresh. (Against Heresies 3.11.8; emphasis added)

Thus from a wide range of sources and genres of writing, we learn that Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were held in high esteem in the late second-century church, and that they were considered authoritative alongside the books of the Old Testament.

Yet not all who considered themselves Christians were satisfied with what would become the canonical foursome. Those who chose a different course, who were called "heretics" from a Greek word meaning "choice," either rejected some of the four gospels or added more to them. Ironically, these heretics strongly influenced the development of the Christian Bible. I'll explain what I mean in my next post. |

|

| |

Peter Paul Rubens, "The Four Evangelists," c. 1614

|

Opportunity #5: How The New Testament Gospels Made It Into the Bible (Section D)

Part 35 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Friday, May 19, 2006

Heretics and the Christian Canon

As Sir Leigh Teabing, The Da Vinci Code's historian-guru spells out how Constantine determined what writings made it into the Christian Bible, Robert Langdon adds:

"Anyone who chose the forbidden gospels over Constantine's version was deemed a heretic. The word heretic derives from that moment in history. The Latin word haereticus means 'choice.' Those who 'chose' the original history of Christ were the world's first heretics." (p. 234)

Well, once again there is a kernel of truth here covered by plenty of chaff. Those who differed from orthodox Christianity were indeed called heretics by the orthodox believers. And the word "heretic" does come from a word that has something to do with choosing. In fact, "heretic" comes from the Latin haereticus, which comes from the Greek word hairetikos, which means "able to choose." At least Dan Brown is in the ballpark here.

But he's certainly not correct in saying that the word "heretic" derives from the time of Constantine. In fact, this word was used extensively over a century earlier by Irenaeus in his treatise Against Heresies. In this long document the Bishop of Lyons explains many of the Gnostic and other Christian spin-offs that he considers to be far from the truth. Their doctrines are heresies, and those who promote them are heretics. They have chosen, Irenaeus might say, but wrongly.

Ironically, however, orthodox Christianity owes a great debt to some of the most notable second-century heretics. These thinkers, by straying far beyond the bounds of acceptable theological diversity, forced the orthodox church to define itself more clearly, and also to define a canon of sacred writings. Thus the heretics were responsible, in a way, for the creation of the orthodox canon of Scripture. Let me illustrate this thesis by talking about two of the most influential heretics of the second century, Marcion and Valentinus. |

|

| |

Tonight I gave a lecture on The Da Vinci Opportunity to a gathering in Austin, Texas. In the question and answer period I was asked for a trustworthy and readable book on church history. The book that came to mind was a volume by Bruce Shelley called Church History in Plain Language. |

Marcion and the Canon

Marcion was an influential Christian theologian and leader in the middle of the second century A.D. He was attracted to the message of Christ as he understood it, but despised the Jewish Scriptures and their God, whom Marcion believed to be a lesser pseudo-god. This false god, according to Marcion, was ethically despicable. He created the world as a reflection of his own evil nature. The God of Christ, on the other hand, was both good and therefore utterly distant from this evil world.

One of Marcion's brilliant moves was to collect and edit Christian writings conducive to his theology. Stripping them of their Old Testament quotations, which Marcion believed to be later insertions, he established a canon that included the letters of Paul and the Gospel of Luke. Though Marcion was kicked out of the church of Rome in 144 A.D., his canon set an example for orthodox Christians, who realized that they also needed to determine which Christian writings counted as sacred Scripture. Marcion forced the church to say what's in, so to speak.

Valentinus and the Canon

Valentinus came about the same time as Marcion. He too was a leader in the Roman church. And he too was excommunicated for his heretical views. Valentinus was one of the gurus of Gnosticism, and may have been the writer of the second century "Gospel of Truth," which we have in the Nag Hammadi Library. Valentinus was a classic Gnostic, believing that matter was evil, and that salvation could be found through esoteric knowledge (gnosis). Unlike Marcion, Valentinus and his followers accepted more books as sacred than did their orthodox competitors. Thus, for a different reason, the orthodox found it necessary to define the books that were sacred and those that were not. Whereas Marcion foreced the church to say what's in, Valentinus forced the church to say what's out.

Irenaeus on Marcion, Valentinus, and the Gospels

In Against Heresies, Irenaeus mentions Marcion and Valentinus explicitly. One particularly significant paragraph comes right after Irenaeus explains that there are, by God's design, four and only four gospels. (I quoted a portion of this explanation yesterday; Against Heresies 3.11.8.) Here's what he writes:

These things being so [that there are four gospels], all who destroy the form of the Gospel are vain, unlearned, and also audacious; those, [I mean,] who represent the aspects of the Gospel as being either more in number than as aforesaid, or, on the other hand, fewer. The former class [do so], that they may seem to have discovered more than is of the truth; the latter, that they may set the dispensations of God aside. For Marcion, rejecting the entire Gospel, yea rather, cutting himself off from the Gospel, boasts that he has part in the [blessings of] the Gospel. . . . But those who are from Valentinus, being, on the other hand, altogether reckless, while they put forth their own compositions, boast that they possess more Gospels than there really are. Indeed, they have arrived at such a pitch of audacity, as to entitle their comparatively recent writing “the Gospel of Truth,” though it agrees in nothing with the Gospels of the Apostles, so that they have really no Gospel which is not full of blasphemy. For if what they have published is the Gospel of truth, and yet is totally unlike those which have been handed down to us from the apostles, any who please may learn, as is shown from the Scriptures themselves, that that which has been handed down from the apostles can no longer be reckoned the Gospel of truth. (Against Heresies, 3.11.9, emphasis added)

Notice what is wrong with the Gospel of Truth, which may be the book by that name in the Nag Hammadi Library. First, it is comparatively recent, and thus not from the days of the apostles. Second, it disagrees with "Gospels of the Apostles," namely, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Irenaeus makes it clear in another place that any genuine gospel must agree with the core theology of these four gospels. After explaining a bit of the nature of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, Irenaeus adds,

These have all declared to us that there is one God, Creator of heaven and earth, announced by the law and the prophets; and one Christ the Son of God. If any one do not agree to these truths, he despises the companions of the Lord; nay more, he despises Christ Himself the Lord; yea, he despises the Father also, and stands self-condemned, resisting and opposing his own salvation, as is the case with all heretics. (Against Heresies 3.1.2. Ironic note: In a church history course in college I wrote a paper on this very passage from Irenaeus. What goes around comes around!)

We can see here the evidence of arguments that would later be central to the orthodox conception of the canon. All canonical documents must agree in the same core theology. All canonical documents must derive from the Lord by way of the apostles.

Athanasius and the Canon

Irenaeus didn't write out the definitive list of the New Testament documents in 180 A.D. That didn't come for two more centuries. In 367 A.D., Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, wrote a letter to other church leaders in which he listed 27 sacred books of the New Testament, the same books recognized today (Letter 39 for year 367). In this letter Athanasius mentions the heretics, showing that he, like Irenaeus, sees the canon of Scripture as a necessary antidote to non-orthodox Christianity:

[N]or is there in any place a mention of apocryphal writings. But they are an invention of heretics, who write them when they choose, bestowing upon them their approbation, and assigning to them a date, that so, using them as ancient writings, they may find occasion to lead astray the simple.

Thus the Christian canon was not a creation by Constantine, but rather by orthodox Christian leaders from the second through fifth centuries, in response to the heretics who identified either too few or too many writings as sacred.

Excursus: Did Constantine Throw Santa Claus in Jail?

Part 36 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Sunday, May 21, 2006

Now before you accuse me of Danbrownian flights of fancy, keep on reading! This could be the ultimate conspiracy of all time: Constantine and the Roman Catholic Church against Santa Claus! Yikes!

Most people are aware of the historical roots of Santa Claus. The jolly man in the red suit derives from an actual human being, St. Nicholas. In a word morphing feat suitable for The Da Vinci Code, just as "sang real" (royal blood) becomes "San Greal" (Holy Grail), "Saint Nicholas" becomes "Santa Claus."

The real St. Nicholas was a Christian bishop from the city of Myra (in modern-day southern Turkey). He served in the early part of the fourth-century A.D., during the time when Constantine was emperor of the Roman Empire. Although we have no ancient written records of Nicholas's life, many traditions have been passed on about him, some of which may be accurate.

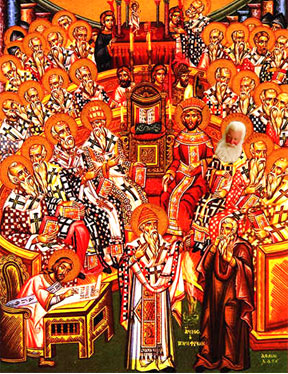

One of these traditions holds that Nicholas attended the Council of Nicaea in 325 A.D., the one called by Constantine to deal with various divisions in the Christian church. If indeed Nicholas was the bishop of Myra during this time, then it's likely that he was in fact at this council, especially since Nicaea was in the same general region as Myra. (Both were in what we call Turkey.)

The story is told that Nicholas was an orthodox theologian who opposed the scandalous innovations of Arius, the man whose theological innovations led to division in the church that prompted Constantine to call the council together. Arius held that Jesus was divine, but not equal to God the Father. Nicholas disagreed, believing that Jesus and the Father shared the very same essence. (Aren't you glad to know that Santa Claus has orthodox theology?) In the beginning of the council, Arius held forth with his views on Christ before the bishops. Nicholas became so enraged that he slapped Arius on the face. This was not only bad manners, but also a crime, given the presence of the emperor. So Constantine (or perhaps the bishops, with Constantine's blessing) stripped Nicholas of his bishop's robes and thus his authority, and threw him into jail so he could not join in the rest of the council.

Yet, during the night, traditional holds that Jesus and Mary (Jesus's mother, not His hypothetical wife) appeared to Nicholas. Jesus gave a copy of the Bible to the future saint, while Mary gave him back his official robes. When the jailer found him in the morning, fully dressed as a bishop and reading Scripture, this was reported to Constantine, who set Nicholas free and restored him to his rightful authority as a bishop. |

|

|

Above: A statue of St. Nichols in the Cathedral of St. Nicholas in Monaco

Below: A slightly altered painting of the bishops of the council of Nicaea. Can you find Santa Claus?

|

|

In the end, the council confirmed the theology of Nicholas, voting almost unanimously against Arius's theology of Christ. Jesus, according to the council, was of the same essence as God the Father, and was not some sort of lesser deity.

So, if this story bears any relationship to what actually happened in Nicaea, then one could truly say that Constantine threw Santa Claus in jail. Don't tell Dan Brown, though, or this could be the impetus of his next conspiracy-driven thriller.

Excursus: The Da Vinci Movie Review Puzzle

Part 37 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Monday, May 22, 2006

Okay, it's time for a little fun before I get back to the heady substance of The Da Vinci Opportunity.

I saw The Da Vinci Code movie on Saturday night, and thought it would be appropriate to put up a brief review. Moreover, in honor of the dearly departed Jacques Saunière, I thought my review should take the form of a puzzle. So, for those of you who think it sounds like fun, you can discover my take on the movie by solving the two anagrams below. The rest of you can come back tomorrow for the answer.

|

|

| |

Admittedly, I'm a bit more prudish than the original Vetruvian man, and less svelte too,

I'm sad to say.

|

Just to be sure you've read this correctly, I'll print out the two anagrams in a legible font:

O drink the can of creedal soda.

I condemn a boring court tyrant.

If you correctly rearrange the letters of each line, you'll find my review of The Da Vinci Code film.

The Contest!

I've decided to make this a contest, with real prizes. The winner will be the first person who sends me an e-mail with the anagrams solved. Here are the prizes:

First prize: Signed copies of two of my books, Jesus Revealed and Dare to Be True (signed for you or the person of your choice); and, unless you wish to remain anonymous, public acknowledgement on my website of your brilliance.

Second prize: Signed copy of my book, Jesus Revealed; and, unless you wish to remain anonymous, public acknowledgement on my website of your secondary brilliance.

Third prize: Signed copy of my book, Dare to Be True; and, unless you wish to remain anonymous, public acknowledgement on my website of your tertiary brialliance.

Again, the winners will be determined according to the order in which I receive your e-mail solutions. Send your entries to: mark@markdroberts.com.

Godspeed!

Excursus: The Da Vinci Movie Review Puzzle Solved

Part 38 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Tuesday, May 23, 2006

| Note: If you're too busy for fun, you can skip to the substance of my review by clicking here. No Holy Grail for you! |

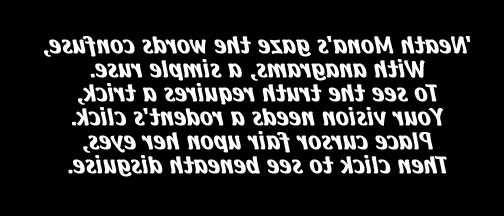

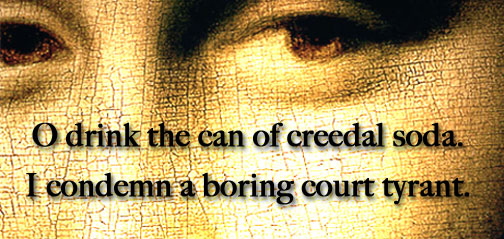

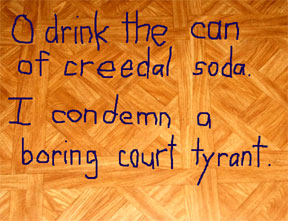

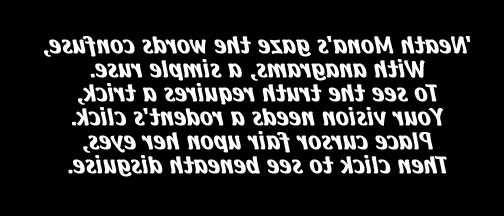

Yesterday I put up my brief review of The Da Vinci Code movie. But, in the cryptographic spirit of the day , my review came in the form of two anagrams. If you missed them yesterday, here they are, once again:

I had several people e-mail possible solutions to this puzzle. They call came up with the same answer, admitting that they used an anagram-solving website, of which there are several (Wordsmith, Anagram Genius). Their guess was:

"O drink the can of creedal soda." = "Darkened, narcotic falsehood."

I condemn a boring court tyrant." = "Brute acrimony and contorting."

These are quite good, actually, and might be good reveiws of The Da Vinci movie. But, alas, they're not what I had in mind. So today I'll reveal the truth.

But . . . .

You didn't think it would be that simple, did you? Visit my site today and that's it? C'mom, this is a revew of The Da Vinci Code movie, after all. Surely I must tantalize you with further puzzling challenges! (Note: If you have no time for this nonsense, or if your browser doesn't deal well with Javascript, click here to see my cryptic review revealed, along with some further comments.)

The two images below will allow you to find the solution to the anagrams, and to discover the essence of my movie review.

(No mirror handy? You can cheat by clicking on the image above.)

For an explanation of my review and further comments, scroll down a bit or click here.

My Review of The Da Vinci Code Movie, Part 1

My brief review came in the form of two anagrams:

O drink the can of creedal soda.

I condemn a boring court tyrant.

When correctly unscrambled, these read:

I declare: So dark the con of Dan.

Nice try, Ron and Tom, but no cigar.

Let me explain a bit further what I mean.

I declare: So dark the con of Dan.

As I'm sure you know, this line is a slightly-tweaked version of a key line from The Da Vinci Code: "So dark the con of man." This is what the dying Jacques Saunière scrawled on the Plexiglass protecting "The Mona Lisa." In the novel, Robert Langdon explains its meaning in this way:

"Sophie," Langdon said, "the Priory's tradition of perpetuating goddess worship is based on a belief that powerful men in the early Christian church 'conned' the world by propagating lies that devalued the female and tipped the scales in favor of the masculine." (p. 124)

Later we learn that this "con" concerns the true nature of Jesus, who was not divine, and who was the husband of Mary Magadelene and father of her child. This "con," according to The Da Vinci Code, is responsible for many of the world's worst ills, thus explaining the con's darkness. But, as it turns out, "So dark the con of man" is also an anagram for Da Vinci's painting Madonna of the Rocks, behind which Saunière had placed a crucial clue.

In my opinion, The Da Vinci Code movie deserves the epitaph: "So dark the con of Dan." First of all, after seeing Dan Brown's story played out on the big screen, I was impressed by the darkness of his vision. In this story, Christianity is based on a colossal lie, and this lie is responsible for terrible things, the Inquisition writ large across the pages of human history. True or not, this is a dark vision, dark in it's lack of truthful light, and dark in its estimation of Christianity. (The movie does try to lighten it up a bit, as I'll explain below.)

Of course I don't believe Dan's vision is true, which is why I call it a con. He is conning the millions of people who take his wild, shadowy fiction as if it were historical truth.

Some of Brown's critics believe he made up all of this stuff out of some hatred for orthodox Christianity in general and the Roman Catholic Church in particular. Surely he's none too fond of Opus Dei, that's for sure! But, given what he has said publicly, it seems as if Dan Brown actually believes that his dark fiction reflects the truth that needs to be revealed. His generous use of the pseudo-historical Holy Blood, Holy Grail, for example, appears to have had a significant impact on Brown's view of history. Thus I believe that the "con of Dan" is not only a matter of his deceiving others, but also of his being deceived by scholars and pseudo-scholars whose anti-Christian bias has colored their writings. Brown seems to have been hoodwinked into believing the dark tale that underlies his novel. Thus "the con of Dan" runs in two directions.

Tomorrow I'll finish up my review of the movie by interpreting the line: Nice try, Ron and Tom, but no cigar.

Excursus: My Da Vinci Movie Review, Part 2

Part 39 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Wednesday, May 24, 2006

Note: Tomorrow I'll review the cover story of Newsweek, which focuses on

"The Mystery of Mary Magdalene." |

Yesterday I put up Part 1 of my review of The Da Vinci Code movie. It was based, as you may recall, on an anagram: "O drink the can of creedal soda." With letters correctly rearranged, this becomes: "I declare: So dark the con of Dan." I explained the meaning of this sentence yesterday.

The rest of my review was summarized in another anagram: "I condemn a boring court tyrant." This becomes, "Nice try, Ron and Tom, but no cigar." Today I'll explain what I mean by this line.

Nice try, Ron and Tom, but no cigar.

Tom Hanks is probably my favorite actor. I loved him in Splash, The Money Pit, Dragnet, Big, A League of Their Own, Sleepless in Seattle, Philadelphia, Forrest Gump, Apollo 13, Saving Private Ryan, You've Got Mail, and The Terminal (yes, even The Terminal). Few actors have given me more laughs and, at other times, have moved me more deeply than Tom Hanks. I must confess that I was less than pleased when I learned that Hanks had taken the role of Robert Langdon, since I've never been a fan of The Da Vinci Code.

I've loved Ron Howard virtually my whole life, since I cut my television teeth on The Andy Griffith Show, where Howard played the beloved Opie Taylor. Howard directed several fine movies, including, Splash, Cocoon, Parenthood, Backdraft, Apollo 13, Ransom, A Beautiful Mind, and Cinderella Man. So I wasn't too keen on having Opie associated with The Da Vinci Code either. Nevertheless, I figured that the combination of Hanks and Howard, combined with Ian McKellen and Jean Reno, would surely produce a fine cinematic version of Brown's runaway bestseller.

My conclusion after having seen the movie: "Nice try, Ron and Tom, but no cigar." As you can tell, I'm a bit more positive than many critics, but not as jubilant as many moviegoers.

Why "nice try?" Well, I think they did many things well. The locations were fantastic (filming inside of the real Louvre, for example!). The actors were well-matched to their roles (except, perhaps, for Hanks). Several actors did a fine job, including Ian McKellen, Audrey Tautou, and Jean Reno. The alterations to Dan Brown's original story were sensible and, in some ways, made the story more believable, not to mention less offensive to Christian viewers. I found the movie modestly enjoyable, overall. What I found most fun, I must confess, was trying to figure out what was new in the film, what changes were made, and what had been left out.

The movie's weaknesses, apart from matters of theology and history, are several, including: excess length, dragging in the second half, and paper-thin characters. But, in defense of Ron Howard, I'd say that these faults are inherent in Brown's novel. Roger Ebert, in his overall "thumbs-up" review (hat tip: Nathan Roberts) of the movie, rightly notes, "Luckily, Ron Howard is a better filmmaker than Dan Brown is a novelist." Once you get through Brown's remarkable cleverness, there's not much there, not enough to sustain a two-and-a-half hour movie, at any rate.

I was impressed by the attempt of the moviemakers to clean up what many Christians find offensive in the novel. Before I saw the film, I had said that, if I were Ron Howard, I'd do this very thing. Once again, I would say today, "Nice try, but no cigar." The problem is that the essential story of The Da Vinci Code requires the fictions of Jesus's marriage to Mary, the deceptive foundations of Christianity, and the conspiratorial Catholic Church. You just can't sweep these under the cinematic rug.

Yet Howard and company worked hard to tidy things up. How? I caught several items as I viewed the film:

• While the novel's protagonist, Robert Langdon, is anti-Christian and an enthusiastic proponent of paganism, the film's Robert Langdon is a lapsed Catholic who is not especially fond of paganism and who seems to have a soft spot for Christian faith.

• While in the novel Langdon gangs up with Leigh Teabing to reveal the secrets of Mary and the Grail to Sophie, in the film Langdon challenges Teabing at points and seems somewhat skeptical of Teabing's scenario.

| |

• In the novel, the Vatican itself knows that its power is based on a lie, and is willing to kill in order to maintain its power. In the film, the Catholic bad guys are the "Council of Shadows." Vatican officials appear to be deceived, but not deceptive murderers. Bishop Aringarosa is transformed from a well-intentioned victim of circumstance to a plotting, self-centered, potential murderer. (But what would you expect from Doc Ock?)

• The film does not include many of the most offensive lines from the book, such as Leigh Teabing's doozy: "almost everything our fathers taught us about Christ is false." (p. 235)

• Many negative statements about Christianity are made in the film, but almost all of them by Leigh Teabing, who is portrayed as being obsessive to the point of potential insanity. Teabing's excess is balanced by Langdon's uncertainty. |

|

|

Perhaps the church should check more carefully into the backgrounds of its bishops. |

|

Nevertheless, if one knew very little about Christianity, and if one were inclined to believe what The Da Vinci Code movie portrays, then one would walk away from that movie believing, not only that Jesus and Mary had a child, but also that Christianity is based on a lie, that the truth about Jesus is to be found in the earlier, non-canonical gospels, and that the Catholic Church (or at least key elements of it) is power-hungry and ruthless. Curiously, the ending of the film leaves open the question of whether or not the world would be better off knowing the truth about Jesus. A similar point is made in the novel by Robert Langdon (p. 342), but not at the crucial dénouement of the story.

So, for the reasons I've noted and several others, I can't give Ron and Tom a cigar for The Da Vinci Code movie. I must confess, however, that I wasn't exactly rooting for them in the first place. Though I appreciate their effort to erase some of the novel's disparagement of Christianity, the bottom line of The Da Vinci Code, in whatever medium, is still a dark, anti-Christian vision.

To keep reading, go to The Da Vinci Opportunity, Section 5

|