| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

The Da Vinci Opportunity, Section 2

How the Popularity of The Da Vinci Code Book

and Movie Can Be Helpful to Christians and Others

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2006 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com. Thank you.

Excursus: Why is Gnosticism Popular Today?

Part 11 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Monday, March 27, 2006

| Gnosticism, in its Christian guise, flourished during the second and third centuries A.D. But it soon fell off the radar of significance and was largely ignored by most people, Christian or not, for centuries. This happened, in part because of orthodox Christian opposition to the Gnostics, and in part because of Gnosticism's own internal flaws (see my last post for details). In the language commonly heard today, the Gnostics were the losers in the religious debate. The orthodox Christians were the winners. |

|

| FAQ: Why is Gnosticism popular today? |

|

Yet the losers have been making quite a comeback in the last few decades. In scholarly tomes and popular paperbacks, Gnosticism takes the spotlight. The Gnostics are often seen, not as the losers in a fair theological debate, but as the victims of orthodox prejudice and power. Gnosticism is the David fighting against the big, horrible Goliath of orthodoxy and the Roman Catholic Church. Many contemporary writers not only defend ancient Gnosticism against its oppressor, but even find personal inspiration from ancient Gnostic writings.

This is a most curious situation. Why would an ancient, esoteric, and sometimes bizarre collection of documents receive such attention today? And why would it inspire many to appreciate if not to adopt Gnostic beliefs? In the rest of this post I'll try to sketch out some reasons for the contemporary resurgence of Gnosticism.

The Attraction of Gnosticism for Scholars

Scholars have been aware of Gnosticism for centuries, largely because many orthodox church fathers (like the second-century bishop, Irenaeus of Lyons) wrote disapprovingly about this amorphous movement in early Christianity. Interest in Gnosticism grew after 1945, when a collection of Gnostic documents was found at Nag Hammadi in Egypt. Yet scholars had to wait for years to have access to the Nag Hammadi tractates. Finally, in the 1970's, the full collection was published for scholars. In 1977, a definitive English translation was published, The Nag Hammadi Library in English. For the first time, people could read for themselves what Gnostic writers actually believed.

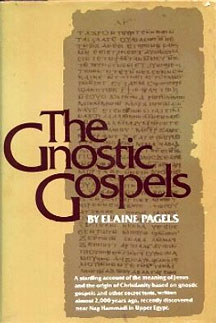

Then, in 1979, Elaine Pagels published her controversial bestseller, The Gnostic Gospels. This book popularized Gnosticism, not only as an academic curiosity, but also as a compelling version of Christianity for folks who could not stomach Christian orthodoxy. (Note: In The Da Vinci Code Sir Leigh Teabing refers to a book called The Gnostic Gospels, [p. 245] which he takes to be a collection of actual documents. In fact, Pagels's book was a discourse about these documents, not a collection of them.) |

|

| |

The original cover of The Gnostic Gospels. |

As I explained earlier in this series, I found myself in the middle of the Gnostic buzz when I was a student at Harvard. In 1978, during my junior year of college, I took a seminar on "Christians, Jews, and Gnostics" with Prof. George MacRae, who had translated several of the tractates for The Nag Hammadi Library in English and was one of the world's leading scholars on Gnosticism. It was exciting to study texts that had received very little scholarly attention with someone who knew them so well. (Prof. MacRae was a major reason I decided to do a Ph.D. in New Testament. He would have been my dissertation adviser, but he died in the mid-80s, just as I was beginning my research.)

When The Gnostic Gospels came out in 1979, I was studying New Testament at Harvard, the very school from which Elaine Pagels had received her Ph.D. nine years earlier. Many of my colleagues were friends of Pagels and cheered her work. Some, I remember, were envious of her wide popularity. A few even criticized her for being a "popularizer," which cut against the elitist grain of scholarship. The professor who was Pagels's dissertation adviser, Helmut Koester, became my dissertation adviser several years later, after Prof. MacRae died. Many of my fellow students went on to build their academic careers as experts in Gnosticism, notably, Ron Cameron of Wesleyan University. So, during my graduate school days, Gnosticism was in the air.

Part of what was so exciting in those days was the chance to dive into original texts that had never been studied before. Until that point of time, most New Testament scholars and graduate students had to rework the same soil that had been turned up by others for centuries. Now we had an unprecedented academic bonanza. These were heady times, especially for scholars who had lost some of their zeal for studying the New Testament itself. Many of my colleagues at Harvard had once been committed Christians, often of a very conservative stripe. Love for Scripture drew them into the academic study of the New Testament. But, somewhere along the way, they lost their belief that the canonical writings were God's gift to us. Some became liberal Christians, without any conviction of biblical authority; others became agnostics, without any religious faith at all. Anti-conservative bias was encouraged by some, but not all of the faculty at Harvard. I remember one of my professors lecturing on the orthodox notion that one must "stand under" the text in order to "understand" it. "That's bull****!" he said, in a classroom filled with 150 seminarians.

Yet some my colleagues who had given up orthodox Christianity still longed for meaning in their lives. They found hope in the interpretations of Gnosticism by scholars like Elaine Pagels, who saw in the Gnostic writings not only a way to forge a successful academic career, but also an appealing alternative to orthodox Christianity. Gnosticism, especially when run through the interpretive grid of postmodern academia, seemed to support many of the values endorsed by liberal- or post-Christian academics. Gnosticism was envisioned to support feminism, religious pluralism, the supremacy of knowledge, the non-divinity of Christ, the non-literal resurrection, and the self as the source of ultimate meaning. Gnosticism also appealed to the elitism that is rampant in academia.

Excursus: Why is Gnosticism Popular Today? (cont)

Part 12 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Tuesday, March 28, 2006

Yesterday I began to explain why, in my opinion, Gnosticism is popular today, especially among academics. My last point was that when ancient Gnosticism is run through the interpretive grid of postmodern academia, it appears to support many of the values endorsed by liberal- or post-Christian academics: feminism, religious pluralism, the supremacy of knowledge, the non-divinity of Christ, the non-literal resurrection, and the self as the source of ultimate meaning.

Many of these values can be found in the Gnostic writings from Nag Hammadi if you dig around carefully. (The whole Nag Hammadi Library, by the way, includes non-Gnostic documents as well.) But these notions are affirmed only through a selective reading of the evidence. For example, some texts do indeed speak positively of Sophia (a divine female revealer) and do indeed refer to the Holy Spirit in female terms. And in some places women, like Mary Magdalene, are held up as inspired revealers. Yet other texts in the Nag Hammadi Library are about as far from feminism as one can travel. (See, for example, my discussion of Gospel of Thomas 114 in this series .)

| Moreover, scholars who have become enamored with Gnosticism generally do not take Gnosticism on its own terms. They do not, for example, actually believe the wild cosmology of many Gnostic writers, with levels upon levels of heavenly beings, and with earth created by a fallen deity. Contemporary scholars reinterpret all of this genuine Gnosticism to suit their own fancy, finding a mythological endorsement of their own pluralistic, individualistic worldview. |

|

| |

The Nag Hammadi codices. |

I don't know any contemporary writer or scholar who actually believes that the highest God sent a non-human Christ to reveal saving knowledge that we have the divine within us. Yet this is the essence of the Gnostic gospel (good news). What today's scholars do with this is to strip away the part they don't like, and recast authentic Gnosticism to make it say something like "you can make up your own truth." This sort of postmodern relativism has nothing to do with genuine Gnosticism, and in fact contradicts it. Whereas the Gnostics believed that truth could only come through revelation from God, contemporary interpreters of Gnosticism believe that we get to create it for ourselves, an utterly non-Gnostic article of faith. (For a similar perspective, see Ben Witherington's excellent discussion in The Gospel Code, pp. 80-95.)

Part of what contemporary scholars like about Gnosticism is its avoidance of the scandal of the resurrection. Orthodox Christians have, from the beginning, proclaimed that Jesus rose from the dead, and that this is essential to the core of Christian faith (see 1 Corinthians 15:1-8, for example). Yet even as the cross once scandalized Jews who did not believe in Jesus, so the resurrection is a stumbling block for modern scholars who tend to look at early Christian history through naturalistic lenses. But then come the Gnostics, who have no need for a real resurrection. Of course they also have no place for a real Christ, or a real crucifixion. But, be that as it may, Gnostic "Christianity" enables one to enjoy the myth of the resurrection with out endorsing its historicity.

Moreover, if one takes The Gospel of Thomas as the paradigm of authentic Christian faith, the resurrection isn't even necessary at all, nor is the cross. So you can have an utterly non-evangelical Christianity, one that doesn't mess around with things like sacrificial death and supernatural resurrection. This kind of Christianity has obvious appeal to many post-Christian scholars.

Gnosticism vs. Orthodoxy: A Power Struggle?

Much of contemporary scholarship has bought hook-line-and-sinker into the interpretation of history as a power struggle between the strong oppressors and the weak but noble oppressed. From this point of view, the mere fact that orthodox Christianity won the battle with Gnosticism makes orthodoxy suspect. This suspicion is supercharged by the historical sexism of the church, not to mention its critique of homosexual practice and its audacious claim that salvation can be found only through Christ. Orthodoxy has dominated, in this view, not because it is true, or surely not because it has been blessed by God, but solely because it was able to manipulate history through an abuse of power. This is the viewpoint of Dan Brown's mouthpiece, Sir Leigh Teabing. The Catholic Church, by getting in bed with the Roman emperor Constantine, was able to suppress non-orthodox Christianity and impose its falsified view of Jesus upon the world.

There is no doubt that during the first few centuries A.D. the church experienced a titanic struggle between Gnostic Christianity and orthodox Christianity. Writers on both sides bore witness to this fact. No doubt there was a power dimension to this battle, and that Constantine's involvement helped orthodoxy, at least in a way. (It's been argued in some quarters that Constantine actually hurt genuine Christianity more than helping it, but this I'll save for another blog series.) If we take seriously the ancient documents we have at our disposal, both the Gnostic writings and the orthodox ones, then we must recognize that those in the midst of the battle saw it, not primarily as a struggle for power, but mostly as a struggle for truth. What was at stake in the battle between Gnosticism and orthodoxy was truth, or perhaps, even better, Truth.

I'll have more to say about this next time. Stay tuned.

Excursus: Gnosticism vs. Orthodoxy as a Battle for Truth

Part 13 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Wednesday, March 29, 2006

Yesterday I explained further why, in my opinion, Gnosticism has been so popular among scholars during the last three decades. My last point had to do with the tendency of scholarship to describe the conflict between Gnosticism and orthodox Christianity as a power struggle between the victims (Gnostics) and the oppressors (The Roman Catholic Church, in league with the Roman Empire). This sort of perspective flows freely through The Da Vinci Code, especially in the revelations of Sir Leigh Teabing.

| Yet I would contend that the battle between orthodoxy and Gnosticism was not primarily about power, but about truth. It was a fight over the nature of God, the world, and human beings. It was a conflict over how people can find salvation, and what that salvation entails. |

|

| FAQ: Was the battle between orthodox Christianity and Gnosticism primarily a power struggle? |

|

Both Gnostics and orthodox Christians believed that there was such a thing as truth, and that this truth mattered for salvation, and that they had it, and that the other side didn't. The contemporary attempt to see in Gnosticism some sort of incipient pluralism misses the boat. Gnostics were every bit as dogmatic about truth as orthodox Christians. They just disagreed about what the truth really was.

Without a doubt, Gnostics believed that they, and they alone, had the genuine truth that sets one free from fatal ignorance and leads to salvation. Consider this passage from the Gospel of Philip (a gospel quoted by Sir Leigh Teabing in The Da Vinci Code).

Ignorance is the mother of all evil. Ignorance will result in death, because those who come from ignorance neither were nor are nor shall be. [. . .] will be perfect when all the truth is revealed. For truth is like ignorance: while it is hidden, it rests in itself, but when it is revealed and is recognized, it is praised, inasmuch as it is stronger than ignorance and error. It gives freedom. The Word said, "If you know the truth, the truth will make you free" (John 8:32). Ignorance is a slave. Knowledge is freedom. If we know the truth, we shall find the fruits of the truth within us. If we are joined to it, it will bring our fulfillment. (83:30-84:13)

Notice that this passage includes a saying of Jesus that appears in the Gospel of John (which was written about a century earlier than the Gospel of Philip, by the way). Both the Gnostics and the orthodox believed in the ultimate importance of truth. Yet they disagreed profoundly on the nature of truth. For Gnostics, the truth included the evil of the material world and its creator, the seed of divinity hidden in the human heart, and the revelation delivered by the Christ who did not die on the cross. For the orthodox the truth included the goodness of creation by the one true God, the fallenness of the human heart owing to sin, and the atonement accomplished by Christ who had to die on the cross to set us free from sin. For Gnostics, the basic human problem is ignorance. Therefore knowledge leads to salvation and freedom. For the orthodox, the basic human problem is sin. Therefore knowledge alone does not save. Faith in response to the cross and resurrection of Christ is necessary for salvation.

The battle between orthodoxy and Gnosticism, though surely at times a power struggle, was fundamentally a battle over the truth, or one might say, the Truth. Today the battle lines are drawn differently, with the very belief in Truth at risk. And, to be sure, at times today's battle is one of power, as academic societies and universities decide who gets to deliver papers, or publish monographs, or receive tenure. In these skirmishes, the tables of power have often been turned, with orthodox Christians taking it on the chin from the powerful who align themselves with the Gnostics. |

|

| |

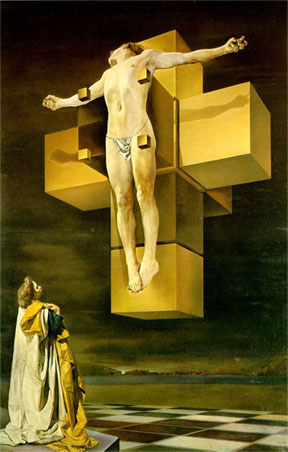

Salvador Dali, "Crucifixion ('Hypercubic Body')", 1954. Although I don't know whether Dali was a modern-day Gnostic or not, his version of the crucifixion would certainly suit Gnostic tastes (no blood, to nails, no real suffering). Confession: This picture hung in my room during my college days. I liked the art, but didn't think about the theology.

|

Yet, as in the first Christian centuries, today's battle is not simply about power. It's really about truth, and whether there is such a thing as Truth, and whether that Truth is to be found in Jesus Christ as He's revealed in Scripture or not. This is one major reason why The Da Vinci Code has become so popular in some quarters, and so maligned in others. The Da Vinci Code clearly rejects the truth of the Bible, advocating an amalgam of Gnosticism and paganism in its place, and claiming Jesus as it's inspiration. Yet, ironically, as I will demonstrate later in this series, much of what The Da Vinci Code promotes is in fact denied in the Gnostic writings upon which the novel depends.

Although I could say much, much more about Gnosticism, I'll stop now. It's time to return to where I left off, and explain why I believe that the biblical gospels are reliable sources of information about Jesus. I'll address this issue in my next post.

Opportunity #1: The Antiquity and Reliability of the New Testament Gospels (Section E)

Part 14 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Thursday, March 30, 2006

Before my recent excursus on Gnosticism, I had been discussing the dating of the gospels, showing that Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, perhaps along with the Thomas, are the oldest of the gospels. Their antiquity gives them an a priori claim to historical reliability, since it's reasonable to assume that a description written chronologically close to an event would be more accurate than one written a long time afterwards.

| But there are many other reasons for affirming the reliability of the New Testament gospels, apart from their relative early date. Several months ago I wrote a lengthy blog series on this very topic: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable? I will not reproduce the details of that series here, but only highlight a few significant points. |

|

| FAQ: Why should one consider the biblical gospels to be reliable historical sources for Jesus? |

|

1. Historical Reliability in Context

The writers of the gospels were creatures of their own time and culture, no matter what you believe about biblical inspiration. They used the common language of the first-century Roman Empire (Greek). They reflected the values of the Greco-Roman-Jewish world in which they lived, such as a concern about hospitality and cleanliness with regard to eating. And they wrote in ways shared by writers of their day. So, for example, though many scholars regard the New Testament gospels as biographies, they do not mean that the gospels fit the modern genre of biography, but rather the ancient genre, in which writing about a person's life tended to be much shorter and focused on key events for the purpose of deriving moral lessons. By modern standards, the failure of the gospels to discuss the childhood of Jesus says they aren't biographies. But this was common to biographical writing in the time of Jesus.

Critics of the biblical gospels often get carried away by minor differences between them. If you compare a story in Matthew, for example, with a parallel story in Mark, you almost inevitably find some modest inconsistencies. In Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable? I cite the following example and offer the following explanation:

Matthew 3:17 - And a voice from heaven said, “This is my Son, the Beloved, with whom I am well pleased.”

Mark 1:11 - And a voice came from heaven, “You are my Son, the Beloved; with you I am well pleased.”

This sort of difference delights detractors of the gospels and perplexes the faithful. It would be pretty hard to argue that the voice from heaven said the same sentence twice in slightly different ways. No, it seems more likely that Matthew and Mark use slightly different words for the same vocal event.

Does this prove that one of the gospels is wrong? Does this mean that either Matthew or Mark was a sloppy historian? Not if we see them in terms of their own time and culture. Yes, we expect historians and biographers to quote their sources with precision. Yet in the ancient world, before there were transcripts, tape recordings, and podcasts, biographers and historians exercised greater freedom in paraphrasing or altering spoken words for stylistic reasons. Quotation marks didn't exist in Greek of the first-century A.D. A good historian, if he knew that a character had made a speech at a certain time, would get available information about that speech and then write the speech with his own words. Nowadays, a historian who did this would be considered sloppy at best, dishonest at worst.

So, when I say that the gospels are reliable as historical sources for Jesus, I'm not applying a standard of reliability that is anachronistic and unfair to the writers. Rather, I'm judging reliability with an awareness of the culture in which the gospel writers did their work. Given this culture, I believe we can have confidence in the picture of Jesus that emerges from the New Testament gospels.

2. The Use of Even Older Sources

Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are the oldest gospels (perhaps including Thomas). They were written within 40-60 years after Jesus's death, by writers who had quite a bit of knowledge of Jesus. Yet most, if not all of the biblical evangelists (gospel writers), used older written sources.

Matthew, Mark, and John do not refer to their sources specifically, though it's likely that they used them (except, perhaps, Mark). Luke, on the other hand, makes clear his dependence on both oral and written materials. His gospel begins:

Since many have undertaken to set down an orderly account of the events that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed on to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and servants of the word, I too decided, after investigating everything carefully from the very first, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the truth concerning the things about which you have been instructed. (Luke 1:1-4)

Luke refers to many "orderly accounts" of the ministry of Jesus. These are written sources Luke used, perhaps including the theoretical sayings source known as Q (from the German, Quelle, meaning "source"). The language of "handing down" is technical language for oral tradition. Luke also got information from "eyewitnesses" who had seen Jesus, and from "servants of the word," teachers and preachers, who passed on sayings of Jesus and told stories about him. (For more on the sources of the gospels, see my series on the reliability of the gospels .) |

|

| |

"St. Luke" by Frans Hals, 1625

|

So when Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John sat down to write, they didn't begin with a blank slate and a creative imagination. Rather, they had done their research, gathering historical data from various sources. The written sources get us even closer to the actual time of Jesus. The oral sources get us all the way back.

One further word on oral tradition. It's common today to think of oral tradition as an ineffective, sloppy means of passing on history. Scholars sometimes write as if those who told stories about Jesus felt free to make them up as they went along. Surely at some point this sort of freedom came into play, especially in the second century when the Gnostics began to reinterpret historical traditions about Jesus to suit their agenda. Yet contemporary research about oral cultures suggests that the early Christians would have been much more disciplined than we might suppose in their storytelling. In fact, though storytellers had certain freedoms, their culture expected them to pass on the core of the story accurately. This was made possible, in part, by the use of oral forms that enhance memorization. These forms are obvious in the gospels. So, those who believe that the earliest Christians made up all sorts of stories and sayings of Jesus would do well to pay closer attention to how oral cultures actually work. This would enhance their confidence in the reliability of the gospels. (For further discussion, see my other series .)

In my next post I'll explain further why the New Testament gospels are trustworthy sources of information about Jesus.

Opportunity #1: The Antiquity and Reliability of the New Testament Gospels (Section F)

Part 15 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Friday, March 31, 2006

Yesterday I began to explain in detail some of the reasons why I believe that the New Testament gospels provide a reliable historical picture of Jesus. My points were:

1. Historical Reliability in Context

2. The Use of Even Older Sources

Today I'll add one further point.

3. Multiple, Early Witnesses to the Basic Gospel Story

The basic gospel story in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John focuses on the death and resurrection of Jesus. Of course these gospels include lots of other material (teachings, miracles, etc.), but they all lead to the climax on Good Friday and Easter.

This is the sharpest difference between the New Testament gospels and the Gnostic gospels. Some of the Gnostic gospels almost completely ignore the death and resurrection of Jesus (like the Gospel of Thomas). Many others insist that Christ didn't actually die, and therefore didn't actually need to be raised from the dead. The Gnostic gospels focus largely on passing on esoteric revelations of Jesus. In the biblical gospels, the teachings of Jesus set the stage for His crucifixion and resurrection.

In Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John we have four, first-century witnesses to the basic gospel story. Most scholars (but not all) believe that Matthew and Luke used Mark, so only two of these witnesses are independent of the others (Mark and John). But this doesn't diminish the historical value of Matthew and Luke. If I'm having a conversation with two friends, and one tells me that the Lakers won tonight's game, and the other friend, hearing the report of the first, confirms what he said, then I have two solid witnesses even though they are not independent. So it makes sense to conclude that in the biblical gospels we have at least four, first-century testimonies to the core of the Christian gospel.

I say "at least" because we have other witnesses from the first century.

One possibility is the Gospel of Thomas, which may be as old as the biblical gospels. It almost completely ignores the cross and resurrection of Jesus. In Thomas, salvation comes from finding the correct interpretation of Jesus's sayings, not from his atoning death (saying 1). There is one mention of the cross of Jesus in Thomas, however, which seems to imply actual knowledge of Jesus's crucifixion (saying 55). But, otherwise, the death and resurrection of Jesus are not significant. It's worth noting, however, that the Gospel of Thomas doesn't deny that Jesus actually died, as do later Gnostic gospels. Moreover, since many of the sayings of Jesus found in the biblical gospels are also found in Thomas, though in slightly different forms, if Thomas is an independent and early source, then this fact supports the basic reliability of the sayings of the New Testament gospels.

But there are other significant, early witnesses to the core of the Christian gospel. In fact, the earliest Christian writings consistently speak of the death and resurrection of Jesus as if they actually happened. I am talking here of the epistles of Paul. His letters to various churches were all written around 50-60 A.D., at least ten years before the gospels were written. (Q, if it existed, may have been written during the same period.) Paul rarely quotes sayings of Jesus, and seems relatively uninterested in His earthly ministry. But the death and resurrection of Jesus make all the difference in the world for Paul, and he mentions them often.

In one of his letters to the Christians in Corinth, for example, Paul writes:

Now I would remind you, brothers and sisters, of the good news that I proclaimed to you, which you in turn received, in which also you stand, through which also you are being saved, if you hold firmly to the message that I proclaimed to you—unless you have come to believe in vain. For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have died. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles. Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me. (1 Corinthians 15:1-8)

Paul wrote this letter somewhere around 55 A.D., or 25 years after Jesus's death. Thus we have here one of the oldest literary witnesses to the essentials of the Christian gospel, which centers in the theological interpretation of the historical death and resurrection of Jesus.

| Note, however, that Paul is not inventing this statement of the basic Christian message. It's something that he had "proclaimed" to the Corinthians during his first visit to Corinth (probably around 50 A.D.). But, notice further, that Paul handed on what he had first received. He refers to the process of oral tradition, by which early Christian beliefs were passed on. So what Paul delivered to the Corinthians around twenty years after the death of Jesus was something that he had received earlier. Exactly how much earlier, we do not know. But it's clear that Paul's traditions about the death and resurrection of Jesus go back to the very earliest strata of Christian belief. |

|

| |

A view of ancient Corinth today. The ruins (mostly) of the city in which Paul preached are surrounded by tile roofed modern buildings. (This picture courtesy of Holy Land Photos.) |

Thus the writings of Paul provide another, clearly independent witness to the most important elements of the New Testament gospels, namely, the death and resurrection of Jesus. These elements are also those that tend to be either omitted or denied in the later Gnostic gospels.

The core of the Christian testimony about Jesus is also found in other New Testament writings, including the 1 Peter, Hebrews, and 1 John. These documents were all written in the latter half of the first century, and add even further support to the reliability of the New Testament gospels in the things that matter most to Christians, and that are denied by the Gnostics.

In conclusion, we have several early witnesses to the ministry and saving work of Jesus, including the four biblical gospels themselves. This cloud of witnesses suggests strongly that Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John paint a historically credible picture of Jesus.

In my next post in this series I want to spell out two further reasons I find the New Testament gospels to be reliable as sources of historical knowledge about Jesus.

Opportunity #1: The Antiquity and Reliability of the New Testament Gospels (Section G)

Part 16 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Monday, April 3, 2006

So far I've been suggesting several reasons why the New Testament gospels can be trusted as reliable witnesses to what Jesus actually said and did. Here are my three main points in review:

1. We must evaluate historical reliability in context.

2. The New Testament gospels are not only the oldest of the so-called gospels, but also they use sources that are older still.

3. There are many, early witnesses to the basic story of the New Testament gospels. These witnesses include the earliest Christian writings, which employ still older traditions.

Today I'll add a further point.

4. The biblical Jesus makes more historical sense than the Gnostic Christ.

| I'll admit that this point is somewhat subjective. Nevertheless, I find it to be persuasive. If you read through Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, you'll observe several distinct pictures of Jesus. Yet these pictures share much in common. Part of this common element is what one might call "Jesus the Jewish prophet." Like the prophets of the Old Testament, Jesus spoke of God and God's rule over the earth. He called for a response to God's sovereignty, promising that God was doing a new thing on the earth. He delivered divine judgment on sinners, and offered salvation to those who responded favorably to God. Unlike the other Jewish teachers of His day, Jesus spoke with God's authority. Jesus even referred to Himself as if he were a prophet (Luke 4:24). Thus it comes as no surprise that many in Jesus's day considered him to be "one of the prophets" (Mark 8:28). Jesus nowhere denied this identification. |

|

| FAQ: Does the picture of Jesus in the biblical gospels make historical sense? Does it make more sense than the picture of Jesus in the Gnostic gospels? |

|

Given everything we know about Jesus's geography, ethnicity, religion, and culture, it makes sense that He would sound like the Hebrew prophets and be associated with them. Though Christians believe that Jesus is more than merely a prophet, we certainly see Him as standing squarely in the prophetic tradition. To put matters simply, the prophetic Jesus makes good historical sense.

In contrast, the Gnostic "Christ" would be lost in the world of Jesus, the first-century Jewish culture of Galilee. If you pay attention to the images of the Savior in the Gnostic gospels, they look very little like a Jewish prophet. Some of these gospels use genuine sayings of Jesus without stripping away their Jewish theology. The Gospel of Thomas, for example, includes this passage, which is reminiscent of the biblical gospels:

The disciples said to Jesus, "Tell us what the kingdom of heaven is like." He said to them, "It is like a mustard seed. It is the smallest of all seeds. But when it falls on tilled soil, it produces a great plant and becomes a shelter for birds of the sky." (20)

Yet elsewhere in Thomas, when Jesus talks about the kingdom of God, He sounds more like a second- or third-century Gnostic than a Jewish prophet:

Jesus saw infants being suckled. He said to his disciples, "These infants being suckled are like those who enter the kingdom." They said to him, "Shall we then, as children, enter the kingdom?" Jesus said to them, "When you make the two one, and when you make the inside like the outside and the outside like the inside, and the above like the below, and when you make the male and the female one and the same, so that the male not be male nor the female female; and when you fashion eyes in the place of an eye, and a hand in place of a hand, and a foot in place of a foot, and a likeness in place of a likeness; then will you enter the kingdom." (22)

|

|

| |

A close-up of Jesus in Salvador Dali's "Last Supper." Here is a fine representation of a Gnostic Jesus.

|

To be sure, the Jesus of the New Testament gospels sometimes acts in ways that are novel and unsettling. In one particularly shocking scene, He assumes the authority of forgive sins (Mark 2:1-12). His scribal opponents are scandalized, noting (rightly) that only God can forgive sins (see, for example, Isaiah 43:25). So by offering forgiveness Himself, Jesus is doing something new and scandalous. Yet His understanding of sin, His acknowledgement of the problem of sin, and His recognition that sin requires forgiveness – all of these are consistent with Judaism in general and the prophetic tradition in particular.

Contrast this biblical Jesus with the Jesus of the Gnostic gospels. In the Gospel of Mary, for example, a gospel favored by Sir Leigh Teabing, by the way, Peter asks Jesus "What is the sin of the world?" (25). Here's the answer:

The Savior said There is no sin, but it is you who make sin when you do the things that are like the nature of adultery, which is called sin. That is why the Good came into your midst, to the essence of every nature in order to restore it to its root. (26-27)

Of course it's always possible that Jesus said this, that He had little in common with Judaism or with the Jewish prophets. It's possible, but highly unlikely. Yes, I admit this is a subjective judgment. But it's one I can defend with evidence and reason. Just about any scholar I know would acknowledge that the Jesus of the New Testament is profoundly more Jewish than the Jesus of the Gnostic gospels.

Moreover, a Jesus who proclaims the presence of God's kingdom and calls people to live under God's reign on earth is a man whom Rome might very well crucify as a threat to Roman imperial order, which was increasingly based on the divinity of the Emperor. A Jesus who speaks of other-worldly salvation, reveals to people that they are divine, and teaches them not to focus on the things of this world is hardly one who would get crucified. So the Jesus of the New Testament gospels not only makes sense in historical and cultural context, but also accounts for one of the rock solid facts about Jesus's life, namely His death on the Roman cross.

In my next post I'll offer one final reason why I find the New Testament gospels trustworthy as historical sources for Jesus.

Opportunity #1: The Antiquity and Reliability of the New Testament Gospels (Section H)

Part 17 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Tuesday, April 4, 2006

Today I'll get into a fifth reason for trusting the reliability of the New Testament gospels:

| 5. The New Testament gospels generously include information that would have been edited out if the early Church had been motivated by a political agenda. The inclusion of such information supports the reliability of the gospels and illustrates the truth-preserving commitment of the Church. |

|

| FAQ: Were the New Testament gospels edited to support the political agenda of the early church? |

|

In The Da Vinci Code, Sir Leigh Teabing describes the effort made by the Catholic Church, in collusion with the Roman emperor Constantine, to produce a Bible that promoted their aspirations to power. At one point Teabing explains, "the early Church literally stole Jesus from His original followers, hijacking His human message, shrouding it in an impenetrable cloak of divinity, and using it to expand their own power" (p. 233). The Church destroyed the "earlier" Gnostic gospels and "embellished those gospels that made [Christ] godlike" (p. 234). Yet the discovery of new documents (which, according to Teabing, include the Dead Sea and the Nag Hammadi "scrolls") "highlight glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications, clearly confirming that the modern Bible was complied and edited by men who possess a political agenda—to promote the divinity of the man Jesus Christ and use His influence to solidify their own power base" (p. 234).

On the face of it, Teabing's thesis is not unreasonable. It's common for people in power to promote self-serving views of history by producing pseudo-historical documents or editing genuinely historical sources to support their own agenda. So, given the fact that orthodox Christians authorized the books of the Bible, we might well expect the sort of thing Teabing alleges, with gospels doctored to augment the power of the Church. (In fact we see this sort of thing going on among the non-canonical gospels. See my discussion in Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?)

What we actually find in the New Testament gospels, however, is the opposite of what Teabing claims. In fact, what we read in these gospels seems, if anything, implicitly to undermine the authority of the Church. Thus the biblical gospels, far from supporting Teabing's assertions, in fact demonstrate the opposite, namely, that the New Testament gospels tell the truth even when that truth would have been embarrassing or inconvenient to the very people who gathered and authorized Christian Bible.

| Remember that the Catholic Church derived its authority from the first disciples of Jesus, and preeminently from Peter. The disciples provided the necessary connection between Catholic authority and Jesus Himself. After all, they were the ones from whom the early traditions about Jesus derived, and were ultimately enshrined in Scripture. And Peter held the "keys of the kingdom of heaven" delivered to Him by Jesus (Matthew 16:19). Moreover, the Catholic bishops claimed to be able to trace their lineage back to the original disciples, who had been directly authorized by Jesus Himself. Catholic authority was "apostolic" in that it was based upon the first apostles, those whom Jesus had sent into the world to make disciples. To this day, the Pope claims to have "apostolic authority." |

|

| |

Domenico Ghirlandaio, "Calling of the Apostles" (detail), 1481, Sistine Chapel, Vatican

|

So, when we turn to the New Testament gospels, given their foundational role within the Catholic church and the fact that they were authorized by people who based their power on the apostles, we would expect Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John to highlight the exemplary qualities of Jesus's disciples, and Peter most of all. The disciples should appear as models of piety and faithfulness, and as people upon whom Christians would be happy to base their church. Yet the truth lies far away from this reasonable expectation. In fact, the disciples of Jesus often appear as foolish, doubtful, and confused . . . or worse. Let me offer some details by quoting a section of my series on the reliability of the gospels.

The disciples of Jesus are first seen in a positive light, as they leave their familiar lives behind to follow Jesus (Mark 1:16-20). But things go downhill quickly from there. For example:

• The disciples consistently misunderstand Jesus (e.g. Matt 16:5; Mark 10:13-14, 35-40; John 12:17).

• They are self-seeking, concerned for their own greatness and glory (Mark 9:34, 10:35-37).

• They lack faith in God or Jesus (e.g. Matt 8:26; Matt 14:22).

• They are rebuked by Jesus for being people "of little faith" (Matt 8:26). Worse still, Jesus once expresses His exasperation over the disciples, "You faithless and perverse generation, how much longer must I be with you?" (Matt 17:17).

• They abandon Jesus in his hour of greatest need, sleeping while He asks them to join Him in prayer at Gethsemane (Mark 14:32-43). Then, when He is arrested, all of them desert Jesus and run away to save their own necks (Mark 14:50). None of the male disciples is present at the cross, except for "the disciple whom Jesus loved" (perhaps John, John 21:20).

• After the resurrection, the disciples disbelieve Mary's report that He is risen (Luke 24:11) and some doubt (or are hesitant) even when they see the risen Christ (Matt 28:17).

If you read through the four biblical gospels, you'll find that the disciples are almost never pictured in a positive light, as paragons of faith or wisdom. Yet time and again they're portrayed negatively. This fact, all by itself, seems to me to disprove the Teabing/Brown thesis. Moreover, it strongly suggests that the early Christians were willing to pass on and preserve the truth, even if that truth portrayed their founding leaders (after Jesus, of course) in an embarrassing light.

Tomorrow I'll complete this discussion with what I take to be the coup de grâce of my argument.

Opportunity #1: The Antiquity and Reliability of the New Testament Gospels (Section I)

Part 18 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Wednesday, April 5, 2006

Yesterday I began to present my last "Da Vinci Code-specific" argument for the reliability of the New Testament gospels. According to Dan Brown's mouthpiece, Sir Leigh Teabing, the biblical gospels reflect a power grab by the fourth-century Catholic Church. But, as I began to explain in my last post, Teabing's thesis has a fatal flaw, one that actually supports the opposite of his position. Thus my fifth reason for affirming the reliability of the biblical gospels is:

5. The New Testament gospels generously include information that would have been edited out if the early Church had been motivated by a political agenda. The inclusion of such information demonstrates the truthfulness of the gospels and the truth-preserving commitment of the Church.

Catholicism, after all, is built on the authority of Jesus mediated through His disciples, whom He made apostles as He sent them out to make disciples of all nations. So if the early Church edited the gospels in light of their agenda, then we'd surely expect to find glorious portrayals of the disciples. They'd be seen as the kind of people upon whom to base a church. In fact, however, the biblical gospels present the disciples as confused and even selfish. Even after the resurrection of Jesus and His appearance to them, some of the disciples "doubted," according to Matthew 28:17. And these are the people upon whom the church is to be built?

I suppose that the gospels could be forgiven for their unflattering picture of the minor apostles. After all, Catholic authority rested preeminently upon Peter, the rock upon which Christ had promised to build His church, and the one to whom He had entrusted "the keys to the kingdom of heaven" (Matthew 16:19). As long as Peter looks good in the gospels, Catholic power is secure.

But, in fact, Peter is portrayed in the biblical gospels as the most egregiously confused of all the disciples. He is more often an example of how a Christian should not act, rather than a moral exemplar upon which to base one's life, or the strong leader upon which one might build a church.

Let me cite a few examples by drawing, once again, on my series Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?:

• In Matthew 14:22-33, the disciples of Jesus are in a boat on the Sea of Galilee. Jesus comes to them from the shore, walking on the water. Peter gets out of the boat in order to approach Jesus. An exemplar of faith? Hardly, because he becomes frightened and starts to sink, crying out to be saved. Jesus refers to him as one with "little faith."

• Though Peter rightly confesses Jesus as the Messiah (Mark 8:27-33), he doesn't really understand what he's saying. So when Jesus reveals the necessity of His death, Peter actually rebukes Him. Jesus responds to Peter by saying, "Get behind me, Satan! For you are setting your mind not on divine things but on human things" (Mark 8:32-33).

• Peter doubly misunderstands the point of Jesus's foot washing, both in not wanting it and then in wanting too much washing (John 13:5-10).

• Peter is obviously special to Jesus since Jesus takes him along to the Garden of Gethsemane. But then Peter, along with two other disciples, keeps falling asleep rather than staying awake in Jesus's hour of turmoil. This is shown to be deeply distressing to Jesus (Mark 14:32-42).

• When the guards come to arrest Jesus in the Garden, Peter draws a sword and cuts off the ear of a slave of the high priest, but Jesus rebukes Peter and heals the slave's ear. Clearly Peter doesn't understand Jesus's intentions. He looks impulsive and foolish (John 18:10).

• Peter, along with the rest of the disciples, runs away when Jesus is arrested (Mark 14:50).

• Though he vigorously rejected Jesus's prediction that he would deny Jesus, in fact Peter denies Jesus three times (Mark 14:30-31; 66-72).

If you haven't read through the biblical gospels recently, you might think that I've picked only those passages that show Peter in a poor light, while ignoring the ones that show him as a strong, wise leader, the kind of leader upon which Jesus would build the Roman Catholic Church. In Acts of the Apostles Peter emerges as this sort of leader, but only because the Holy Spirit fills him with power. The gospels don't paint a flattering portrait of Peter at all.

I think the presentation of Peter in the New Testament gospels shows the folly of the "power grab" theory of gospel production and authentication. But it also shows something quite astounding about early Christian oral tradition and the writing of the gospels. Those who passed on and wrote down the actions and sayings of Jesus were committed to telling the truth, even when this truth was embarrassing to the most prominent leaders of the early church. Surely it was only a strong commitment to historical accuracy that kept such a negative portrayal of the disciples, including Peter, in the New Testament gospels. This same commitment guided the Catholic leaders who authorized the New Testament, even when it showed the ample follies of their ecclesiastical predecessors. |

|

| |

The interior of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

|

If Sir Leigh Teabing had ever read the New Testament gospels, surely he, as a historian, would have been struck by how much these documents preserve the truth even when it undermines Roman Catholic power. Of course he'd also be astounded by how much more human Jesus appears in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John than in Philip, Mary, Thomas, and Truth. But, as a fictional character, we can't actually hold Sir Leigh responsible for not having read the documents that figure so prominently in The Da Vinci Code. As to Dan Brown, however . . . .

Opportunity #2:

The Engagingly Human Jesus of the Biblical Gospels: Section A

Part 19 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Thursday, April 6, 2006

| People these days are yearning for a truly human Jesus. They want a Jesus they can relate to, a Jesus who knows what it's like to be one of us, a Jesus who enjoys the good things of life and knows what it is to hurt, a Jesus who, as real flesh and blood, felt genuine human emotions and lived as a real man. |

|

| FAQ: Why has the idea of a married Jesus become so popular? |

|

I'm convinced this is one reason for the astronomical sales of The Da Vinci Code, in addition to an engaging plot and some mind-boggling codes. The novel, and the movie yet to come, seems to offer a truly human Jesus. This Jesus, claimed by The Da Vinci Code to be the real Jesus of history, demonstrated His humanity most profoundly by doing one of the things that real human men do: marrying Mary Magdalene and fathering a child through her.

A couple of years ago, in response to the excitement over The Da Vinci Code, I wrote a short series for my website called: Was Jesus Married? A Careful Look at the Real Evidence. I surveyed every bit of the historical evidence for the supposed marriage of Jesus to Mary Magdalene, showing how little evidence there is. I also explained how the biblical picture of an unmarried but discipled Mary in fact honors her more than the fictional image painted by Dan Brown.

I was astounded by the number of people who read my little series on the supposed marriage of Jesus. This was one of my first experiences as a blogger of the power of the Internet. According to the software that keeps tabs of such things, I've had over 40,000 visitors check out Was Jesus Married?

Literally hundreds of these visitors have written to me over the past two years. 95% wrote to thank me for helping them to have access to the historical evidence. But a couple dozen e-mailers scolded me for being a lousy scholar and an insensitive human being. In fact, some of the meanest e-mails I've ever received were from people who were angry that I had denied the marriage between Jesus and Mary Magdalene. "Why?" I wondered. "Why would folks be so passionately committed to a belief that had so little historical evidence to back it up?" Some of those who were upset with me claimed to be orthodox Christians who believed in the deity of Christ, His saving death, and His resurrection. Yet they also believed Jesus was married, and were stoutly committed to that conviction. Why? Why did it matter so much to them?

Finally a friend explained it to me. She was a solid Christian who was sorely tempted to believe that Jesus had been married. This is what she said to me, as I remember the conversation: "A married Jesus is someone I can relate to. I believe He's God and everything. But a married Jesus is, well, so human. It's like He's actually one of us." As I listened to this friend, and as I dialogued with others through e-mail, I heard a common refrain. "The Jesus I grew up with was so much God that He wasn't really human. I could never relate to that Jesus."

So The Da Vinci Code, by presenting the "secret" of Jesus's marriage to Mary, gave people hope that Jesus was truly human, that He was somebody they could relate to personally. Many of these folks weren't denying His deity as does The Da Vinci Code. Rather, they were finding in the novel a way to draw near to the Jesus they believed to be God, but could never quite relate to as human.

According to Dan Brown's fictional mouthpiece, Sir Leigh Teabing, the truly human Jesus, who among other things was married to the Magdalene, is to be found in the Gnostic gospels, rather than the biblical ones. To review what I've already explained in this series, Teabing claims that the non-canonical gospels "spoke of Christ's human traits" and described His ministry "in very human terms" (p. 234). Thus the early Church " literally stole Jesus from His original followers, hijacking His human message, shrouding it in an impenetrable cloak of divinity, and using it to expand their own power." |

|

| |

Ian McKellen, as Sir Leigh Teabing, doesn't look too happy in this scene from the film.

|

But the Church wasn't able to destroy all of the non-canonical gospels that depicted Jesus's true humanity. Some of these were found, according to Teabing, among the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi documents. I explained earlier that there are no gospels to be found in the Dead Sea Scrolls, but several "gospels" do show up in the Gnostic collection found at Nag Hammadi, Egypt. This allows us to weigh Teabing's claims in the balance of history. Do the Gnostic gospels present a truly human Jesus? Or can this Jesus be found, rather, in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John?

You can guess how I'm going to answer these questions from the way I entitled the second opportunity of this series: The Engagingly Human Jesus of the Biblical Gospels. In my next post I'll explain what I mean.

Opportunity #2:

The Engagingly Human Jesus of the Biblical Gospels (Section B)

Part 20 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Friday, April 7, 2006

| Many years ago I saw Pier Paolo Pasolini's film, The Gospel According to St. Matthew. Made in black and white in 1964, this was a controversial film because it depicted Jesus, not as some air-brushed holy man, but as a rabble-rousing peasant. Pasolini's Jesus was terse and almost harsh in His many proclamations, which came verbatim from the biblical Gospel of Matthew. In some ways I liked this Jesus, because He seemed more down to earth than other representations. Yet Pasolini's image of Jesus missed the fully human dimension of the man almost as much as more beatific visions from Sunday School film strips. The real Jesus was so much more than someone who made socially unacceptable speeches and then moved quickly to the next venue where He could stir up trouble. He was a real man who experienced the richness and poverty of real humanity. |

|

| |

Pasolini's Jesus

|

| The biblical gospels portray Jesus as more than a man, no question about it. Matthew and Luke testify to His miraculous birth. Mark identifies Jesus as "the Son of God" in verse 1. And John begins by equating Jesus with the divine Word of God who created all things (1:1-14). |

|

| FAQ: Which gospels portray Jesus as more fully human, the biblical gospels or the Gnostic gospels? |

|

Yet these same gospels portray Jesus as a real person. Though miraculously conceived, Jesus was born in the ordinary way. He experienced such genuinely human realities as anger (Mark 3:5), exhaustion (John 4:6), compassion (Mark 6:34), impatience (Mark 9:19), lack of knowledge (Mark 13:32), love (Mark 10:21), weeping (John 11:35), joy (Luke 10:21), grief (Mark 14:34), thirst (John 19:28) and uncertainty about His divine calling (Mark 14:36). Jesus touched lepers (Matt 8:3), ate with notorious sinners (Mark 2:16), and embraced children (Mark 10:16). When He was beaten and crucified, the Jesus of the biblical gospels spilled real blood and felt real pain. To be sure, Jesus did and said unusual things. But Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John paint a picture of a truly human Jesus.

None of this is to be found in the Gnostic gospels. To the extent that Jesus shows up there, He's depicted almost exclusively as a revealer of heavenly truth. The Gnostic gospels include almost no narrative of Jesus's life. What little narrative appears is there only to set up the discourses of Jesus. In the Gospel of Thomas, the dialogue between Jesus and His disciples seems at times as if it reflects genuine conversations. In the other Gnostic gospels the interactions between Jesus and His followers are brief and unrealistic.

If you want to check for yourselves, I'd encourage you to look briefly at some of the actual Nag Hammadi documents. There are are five documents called gospels:

If you were to spend even a few minutes sampling these documents, you'd quickly get their flavor, and realize that a human Jesus is not to be found here. (If you really want to stretch your mind a bit, read the first ten paragraphs of The Gospel of the Egyptians. Then think about Leigh Teabing's comments about the more human Jesus and have a good laugh.)

There are several other documents in the Nag Hammadi collection, which, though not called gospels, contain revelations of Christ, and some minor narrative. They are:

The Dialogue of the Savior

The Apocryphon of James

The Sophia of Jesus Christ

The Book of Thomas the Contender

If you want to evaluate my judgment of the Gnostic gospels, go ahead and check these out as well. Once again, you'll realize that the human Jesus is not to be found here.

It's no accident that the Gnostic gospels show little interest in the human Jesus, including His actions and emotions. Gnosticism, at its core, denigrates fleshly life, prizing immaterial spirit above all. So a true Gnostic would have no interest in the human Jesus. What matters most about Him, from a Gnostic point of view, is the content of His revelations, since these supposedly enable us to achieve spiritual immortality. The so-called "Gnostic gospels" aren't really gospels at all, but rather collections of esoteric sayings and discourses attributed to the Savior, who is sometimes connected to Jesus.

But, once again, let me invite you not to take my word for it. Perhaps the quickest cure for a naïve admiration of Gnosticism is taking time to read actual Gnostic writings. And when it comes to finding a truly human Jesus, Gnosticism is about the last place you'd want to look. The New Testament gospels are the first and only place to look.

To continue reading The Da Vinci Opportunity, click here to go to Part 21.

|