| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

The Da Vinci Opportunity, Section 1

How the Popularity of The Da Vinci Code Book

and Movie Can Be Helpful to Christians and Others

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2006 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com. Thank you.

Are you looking for quick answers to specific questions about The Da Vinci Code?

If so, check out

The Da Vinci Code FAQ:

Answers to Frequently Asked Questions

About The Da Vinci Code

Here It Comes, Ready or Not!

Part 1 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Monday, March 13, 2006

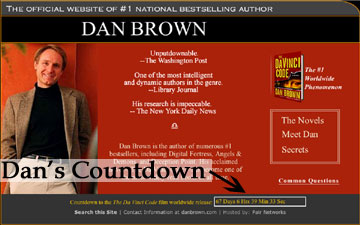

According to the official website of Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code film will be released in exactly "67 Days 6 Hrs 41 Min 56 Sec" and counting. On May 19, 2006, the movie will be shown throughout most of the world. (If you're feeling impatient, you can jet over to France or the United Arab Emirates, where the film will come out on May 17th.)

The Da Vinci Code movie will be a huge blockbuster. No question about it. No need to solve arcane codes to figure this out. How do I know this? Consider the recipe for this film: |

|

| |

Of course by the time you read this, the countdown will be lower.

|

Start with a bestselling novel (over 40 million copies in over 40 languages worldwide) that features a thrill-ride story and a controversial secret;

Add several parts all-star cast, including Tom Hanks, Ian McKellen (aka Gandalf), Alfred Molina (aka Doc Ock);

Then add one Oscar-winning director (Ron Howard);

Shoot in some fantastic locations, including the Musée de Louvre in Paris and The Temple Church in London;

Promote the film with a gripping trailer;

Then top it off with a publicity-generating lawsuit.

And, voilà, you have a certain blockbuster. I'd predict that The Da Vinci Code movie will end up high on the all-time worldwide box office chart, nearing a billion dollars in ticket sales.

On the one hand, this is good news. I love a cinematic thriller, even when I know how the story ends. And Tom Hanks is perhaps my favorite actor. Ian McKellen ranks right up there, whether he's playing Gandalf in The Lord of the Rings or Magneto in X-Men. Ron Howard has directed some of my favorite films, including Cinderella Man, A Beautiful Mind, and Parenthood. (Okay, I can forget about How the Grinch Stole Christmas.) So I fully expect that on May 19th, I will be in for an electrifying ride.

On the other hand, the advent of The Da Vinci Code movie is not good news. Central to its plot are fictional elements presented as if they were true that rub against my Christian faith. This is the case even though I'm not part of the Roman Catholic church (portrayed as sinister in the Dan Brown's story) or Opus Dei (a group within Roman Catholicism that's depicted as twisted and diabolical). The most unsettling elements of The Da Vinci Code are not incidental to Christian faith, however. They have to do with the very core of Christianity. They concern the mission, identity, and nature of Jesus, as well as the inspiration and truthfulness of the Bible.

For example:

| Whereas orthodox* Christians believe that the kingship of Jesus was not about royal blood and earthly government, in The Da Vinci Code the ultimate significance of Jesus is precisely about these things. |

|

| FAQ: What elements of The Da Vinci Code are contrary to orthodox Christianity? |

|

Whereas orthodox Christians believe that Jesus remained single throughout his life, The Da Vinci Code reveals that He was in fact married to Mary Magdalene.

Whereas orthodox Christians believe that Jesus's death and resurrection were the center of His earthly mission, The Da Vinci Code sees His chief contribution as fathering a child by His wife, Mary.

Whereas orthodox Christians believe that the Bible, though written by human beings, is divinely inspired, The Da Vinci Code reveals that it is merely a human invention.

Whereas orthodox Christians believe that the New Testament gospels are reliable sources of information about Jesus, in The Da Vinci Code, the trustworthy gospels come from other collections, like The Dead Sea Scrolls or the Gnostic library from Nag Hammadi.

Whereas orthodox Christians believe that Jesus was fully God and fully human, The Da Vinci Code shows that Jesus was in fact a mere mortal, and that His deity was invented in order to augment the power of the fourth-century Roman emperor Constantine.

I could go on for a while longer with more examples of how The Da Vinci Code contradicts classical Christian belief, but I think you get the point. It's pretty obvious why an orthodox Christian like me would be unsettled by the release of The Da Vinci Code movie and its guaranteed popularity.

Then again, maybe you think I'm completely missing the point. After all, The Da Vinci Code was first a novel. It was written and sold as a work of fiction. Thank God, we don't have any of the complications of A Million Little Pieces, where a substantially fictional work was sold as if it were completely true. (For my comments on the James Frey and A Million Little Pieces controversy, click here.) No bookstore, to my knowledge, has placed The Da Vinci Code in the non-fiction section. So, you might wonder, if a novel contains information that is fictional, even if this information relates to an important historical figure like Jesus, what's the problem?

In my next post I'll explain why I think it's necessary to deal with some of the fictional elements of The Da Vinci Code from a historical point of view, treating them as if they were non-fiction, even though the novel and the film are clearly fictional.

*Note: When I speak of "orthodox" Christians I mean those who affirm the classic Christian faith as contained in the Nicene Creed and The Definition of Chalcedon. The contents of these confessions, which have largely to do with the nature of God and Jesus, have been affirmed by Christians for sixteen centuries. To be sure, there are some Christians, or people who claim to be Christian, at any rate, who do not affirm these core beliefs. These folk are not "orthodox" (which means, literally, "right believing.") "Orthodox" Christians, with a capital 'O', are those who belong to one of the branches of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Orthodox Christians are also orthodox, in that they affirm classic Christian doctrine as contained in the historic creeds.

But It's Just Fiction!

Part 2 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Tuesday, March 14, 2006

| In my last post I summarized some of the ways in which The Da Vinci Code contradicts classical, orthodox Christian belief. It's not hard to imagine how a book that denies the inspiration of the Bible, the reliability of the New Testament gospels, and the deity of Jesus Christ might be upsetting to Christians. |

|

| FAQ: Why worry about "historical claims" in The Da Vinci Code since it's just a work of fiction? |

|

"But," you might want to respond, "it's just fiction! It's a novel, for God's sake. It's going to be a fictional movie. Why get so worked up about fiction? Why refute fiction as if it were fact? Why get so worried about apparently factual elements of a fictional story?"

I can't tell you how much I wish every reader of The Da Vinci Code, and every viewer of the upcoming film, had this perspective. If everybody who was exposed to Dan Brown's story concluded, "Well, that was a great ride, but his stuff on Jesus was a lot of hooey!" then I could start blogging on something else, rather than exercising myself on this topic for the next several weeks. But, I'm sad to say, millions upon millions of readers and viewers of The Da Vinci Code will not reject its treatment of Jesus and early Christianity as wildly creative fiction. In fact, they will believe that Dan Brown has revealed the truth about Jesus. And they'll believe this passionately. |

|

| |

The Da Vinci Code? What, me worry?

|

I know because of the e-mail I have received in response to my online article Was Jesus Married? A Careful Look at the Real Evidence, and the published version of this piece that forms an appendix to my book, Jesus Revealed. I've received dozens of notes from people who not only reject my view that the evidence doesn't support the hypothesis of Jesus having been married, but also are just plain angry with me. They have found the "evidence" of The Da Vinci Code to be so persuasive, and they are so attached to the idea that Jesus is married, that my rather sober treatment of the historical evidence carries no weight whatsoever. The folks who have written to me didn't take Dan Brown's view of Jesus as clever fiction, but as hardcore fact.

They're not alone. Lest you think my blog readers are a bunch of crazies, consider the following evidence:

In a beliefnet.com survey, 27% of respondents said that Mary Magdalene was "Jesus' wife."

Not to be outdone, one in three Canadians who read The Da Vinci Code believe "there are descendants of Jesus alive today and a secret society exists dedicated to keeping Jesus' bloodline a secret."

A more recent Canadian survey found that 17% of all Canadians and 13% of all Americans are of the opinion that “Jesus’ apparent death on the cross was faked” and that "Jesus was also married and had a family." If accurate, this means that tens of millions of North Americans believe Dan Brown's fictions to be true.

There's no denying the fact that millions of people have been influenced by The Da Vinci Code to believe things about Jesus that are contrary to orthodox Christian belief, and that are, as we shall later see, highly improbable and unsupported by the available historical evidence.

| Yet you can't exactly blame the readers of The Da Vinci Code for taking many of its claims about Jesus as historically valid. In the unfolding of the story, "facts" like the marriage of Jesus and the unreliability of the biblical gospels are "revealed" as common knowledge among informed Christians. At one point the novel's historian-guru Sir Leigh Teabing notes, "The vast majority of educated Christians know the history of their faith," which includes the "fact" that Jesus was just a mortal who was elevated to deity by the Roman emperor Constantine to augment his power (p. 234). |

|

| FAQ: Why do people believe that fictional elements of The Da Vinci Code are historically accurate? |

|

Furthermore, the first page of The Da Vinci Code contains a claim about the factuality of the material in the book. It reads: "All descriptions of artwork, architecture, documents, and secret rituals in this novel are accurate" (p. 1). Yet it is in the description of ancient Christian documents that Dan Brown makes some of his wildest claims about the Bible and Jesus. The first page of the book suggests that he is speaking historical truth.

Curiously enough, Dan Brown seems not to have read his own first page. His own website asks Brown, "But doesn't the novel's 'fact' page claim that every single word in this novel is historical fact?" [MDR note: What a ridiculous question!], Here is Brown's answer:

If you read the "FACT" page, you will see it clearly states that the documents, rituals, organization, artwork, and architecture in the novel all exist. The "FACT" page makes no statement whatsoever about any of the ancient theories discussed by fictional characters. Interpreting those ideas is left to the reader.

Hmmm. Actually, his "FACT" page says that "all descriptions" of these things are true, not that they merely exist. When Teabing describes an ancient document, Dan Brown the author suggests that his description is factually true. Dan Brown the webmaster suggests only that the document exists. Will the real Dan Brown please stand up?

| In fact, the real Dan Brown has made known his personal views on the purportedly historical background to his novel. And there's little doubt that he believes the stuff Leigh Teabing feeds to Sophie Neveu is historical fact. For example, Brown's website asks him, "The topic of this novel might be considered controversial. Do you fear repercussions?" Brown answers: |

|

| FAQ: Does Dan Brown himself believe that his fictionalized "history" of Jesus and early Christianity is true? |

|

No. As I mentioned earlier, the secret I reveal is one that has been whispered for centuries. It is not my own. Admittedly, this may be the first time the secret has been unveiled within the format of a popular thriller, but the information is anything but new.

Notice, Dan Brown "reveals" a secret that is really true, and that has been known for centuries, but not widely.

In an interview with bookreporter.com, Brown revealed more of his personal beliefs regarding Jesus and early Christianity. Question: Is this book anti-Christian? Answer:

No. This book is not anti-anything. It's a novel. I wrote this story in an effort to explore certain aspects of Christian history that interest me. The vast majority of devout Christians understand this fact and consider The Da Vinci Code an entertaining story that promotes spiritual discussion and debate.

Note: Brown wrote "to explore certain aspects of Christian history."

Bookreporter.com Question: What do you think of clerical scholars attempting to "disprove" The Da Vinci Code? [MDR note: It's not just clerical scholars, but academic scholars as well.] Answer:

The dialogue is wonderful. These authors and I obviously disagree, but the debate that is being generated is a positive powerful force.

Note: Brown could have said. These folks are crazy. My novel is just a novel. What's their problem? Instead he said, "These authors and I obviously disagree." Upon what do they disagree? On the historical facts. Brown really believes the stuff he puts into the mouth of Leigh Teabing.

In an interview in a National Geographic documentary on The Da Vinci Code, Brown added:

I began as a sceptic. As I started researching Da Vinci Code I really thought I would disprove a lot of this theory about Mary Magdalene and holy blood and all of that. I became a believer.

So, the reader who takes Teabing's revelations as historical fact, and who reads the "FACT" page as indicating that the novel is based on supposedly solid historical data, is not naïve and mistaken. In fact, this reader is tracking perfectly with Brown, who believes his novel reveals a secret about Jesus that is historically true, and a perspective on early Christianity that tells the real story.

Given the influence of The Da Vinci Code, and the tendency for millions of readers to believe the Dan Brown/Leigh Teabing view of Jesus and early Christian history, it's necessary to deal with part of The Da Vinci Code as if it were a work of non-fiction. The "What, me worry?" approach isn't possible for those of us who care about the truth, not to mention the truth about Jesus, His nature and mission.

Where I'm Coming From

Part 3 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Wednesday, March 15, 2006

For those of you who aren't from my part of the world, sorry for the Californianism. At least I didn't entitle this blog entry, "Where I'm At." My point in this post is to talk about what others might call my background, or still others my agenda, or even my bias. I want to explain my perspective as I approach The Da Vinci Code, so you can weigh my insights judiciously. My regular blog readers know most of this already, but others deserve to know where I'm coming from, as we say out West.

Academic Background

As an undergraduate, I majored in philosophy. During my junior year I took a religion course entitled, "Christians, Jews, and Gnostics." It was taught by Professor George MacRae of Harvard Divintiy School. Professor MacRae had been active as a member of the academic team that had translated the Nag Hammadi Library (sometimes called the Gnostic gospels). Thus I was able to read several of those documents with one of the world's experts in the material. It was a fascinating exercise.

My experience in this undergraduate course was part of what led me to seek a Ph.D. in New Testament. I stayed on at Harvard because the New Testament faculty at that time was one of the strongest in the world. I should hasten to add that I'm speaking here in terms of secular academia. Folks from conservative Christian backgrounds would have considered the Harvard New Testament faculty to be unbalanced, heavily weighted in the direction of liberal, critical scholarship.

While in grad school, I spent more time studying ancient documents outside of the New Testament than the New Testament writings themselves. I read most of the Nag Hammadi Library texts, sometimes with those who had made the definitive translations. I also worked on the Dead Sea Scrolls with one of the premier scroll scholars, a man who had been part of the original translation team. In one course I had the privilege of studying, not the actual scrolls, which were locked safely away, but photographs of those scrolls which had not yet been published or translated into English.

It never occurred to me that my years of reading the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Nag Hammadi codices, and other extra-biblical writings would ever have any practical significance. Who in the world would care about "The Temple Scroll" or "The Thunder, Perfect Mind"? Now, thanks to Dan Brown, my knowledge of the Gnostic gospels turns out to be quite timely.

Since finishing my Ph.D. in New Testament, I've done quite a bit of teaching on the seminary level. I've been able to keep up with some of the scholarly literature in my field, especially that which pertains to Jesus. In 2001 I wrote the manuscript for my book Jesus Revealed. Although a popular more than a scholarly book, my research for this book caught me up on the academic study of Jesus and the gospels, including the Gnostic gospels. |

|

| |

One of my proudest days, when I finally received my PhD degree, after 12 years as a grad student, and 17 years of paying some sort of tuition at Harvard. Yikes!

|

So, when I examine the historical evidence for Jesus, and when I speak about the early Christian gospels, I'm relying on my academic background, and can speak with a measure of authority. Though I'm not as current on scholarship as if I were teaching in an academic institution, I can address the issues raised by The Da Vinci Code with a fair amount of scholarly mettle. This doesn't mean my opinions will always be right, of course. There is a wide range of disagreement among scholars about many things pertaining to Jesus and early Christianity. My voice falls in this range as one option among many. But, as I speak about these things, at least you can be assured that I actually have some idea what I'm talking about, whether I'm right or wrong.

Religious Background

I've been a Christian for more than forty years, having "accepted Jesus into my heart" at a Billy Graham crusade in Los Angeles in 1963. I grew up in an evangelical Presbyterian church. In college and grad school I sojourned in other Christian traditions for a season, including Pentecostal, Roman Catholic, and Mennonite. In the end, I found my religious home in the tradition were I was raised, evangelical Presbyterian.

Will my Christian faith influence the way I evaluate the historical evidence for Jesus and the early Christian gospels? Of course it will, to some extent. I'm postmodern enough to realize this. No scholar is immune from the influence of his or her personal convictions. But I'm also rather modern in the sense that I value truth in a more or less absolute sense. Thus I try as a historian to evaluate evidence with as little bias as possible. One of the reasons I've laid out my personal faith here is so that you can do the same. If my historical arguments seem to be "privileging" orthodoxy, at least you'll know why.

The title of this blog series, The Da Vinci Opportunity, intentionally shows my hand. I see the popularity of The Da Vinci Code as an opportunity, not only to discuss Jesus and early Christianity, but also for Christians to explain why we find the Jesus of the gospels to be so compelling, and why we can have confidence in the New Testament portrayal of Jesus. I'll have more to say about this in my next post.

A Threat or an Opportunity?

Part 4 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Thursday, March 16, 2006

Given the various ways that The Da Vinci Code contradicts the core of classic Christian faith, it's no wonder that many Christians have considered the book and the soon-to-be released movie as threats to Christianity. After all, when one of the most popular books of all time claims that the Bible is merely a human document and that Jesus was only human, Christians rightly regard this as a danger to their own faith and to that of others. Moreover, if one is a Roman Catholic Christian, the offense of The Da Vinci Code is far greater still.

| If The Da Vinci Code is a threat, then Christians need to play defense. We must fend off the threat. We should use reason and evidence to show that many of the apparently historical claims of The Da Vinci Code are, in fact, fictional in the extreme. For example, anyone who actually believes that the Gnostic gospels give us a more human Jesus than the biblical gospels has never read the Gnostic gospels. There's no question in my mind that part of what Christians must do in the face of the Da Vinci challenge is to defend orthodox Christianity. After all, when a central character in the story says that "almost everything our fathers taught us about Christ is false," (p. 235) you've got to admit "them's fightin' words." |

|

| |

If The Da Vinci Code is a threat, then we'd better be ready to play some good defense, or it will slip right by us.

|

But I'm convinced that The Da Vinci Code is far more than a threat to orthodox Christianity. It is also an opportunity of the first degree. Yes, I wish that this wildly popular novel and soon to be blockbuster movie presented a picture of Jesus more consistent with historical and theological truth, rather like The Passion of the Christ. But even if The Da Vinci Code itself isn't much of a help in leading people to a true understanding of Jesus and early Christianity, at least it gets them interested. After being exposed to Dan Brown's view of things, people are curious. They ask questions they might never have uttered before, like:

Was Jesus really married?

What was his mission really all about?

Are the New Testament gospels reliable sources of information about Jesus?

Is Gnostic-flavored Christianity really a tastier variety than bland vanilla orthodoxy?

Was Jesus divine?

When did people start believing this?

What can we really know about Jesus?

And why does He matter so much, anyway?

In my opinion, these are great questions. In fact, I believe they're some of the most important questions in life. If it takes something like The Da Vinci Code to get folks asking questions like these, then I am grateful to Dan Brown for his effort, at least to this extent. He's opened the door for serious discussion about Jesus. We Christians, and all truth-seekers everywhere, for that matter, need to thank him for the welcome and walk through the door.

Of course, as an orthodox Christian myself, I seem to be assuming that an open-minded discussion of Jesus and early Christianity will be helpful to the Christian cause. Folks who take the Dan Brown/Leigh Teabing side obviously believe that this conversation will favor their perspective. But, I must confess at the outset, I don't see it their way. In fact, as one who has spent a whole lot of life studying the documents from which we learn about Jesus and early Christianity, I'm utterly convinced that the evidence leans heavily in the direction of classical Christian faith. I'm not suggesting that I can prove that Jesus was divine. Such proof is beyond human capacity. But I am absolutely sure, for example, that I can show beyond any reasonable doubt that most Christians considered Jesus to be divine long before Emperor Constantine had anything to say about it. The Da Vinci Code's purported "history" of early Christian doctrine has everything to do with a thrilling novel and nothing to do with the facts. When it comes to the issues raised by The Da Vinci Code, my encouragement to orthodox Christians comes down to this: The facts are on our side.

In my next post I'll spell out in greater detail how I envision The Da Vinci Opportunity. I will explain the topics I intend to address in the rest of this series.

The Opportunities of The Da Vinci Opportunity

Part 5 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Friday, March 17, 2006

In my last post I explained that, though The Da Vinci Code does indeed pose a threat to classical Christian faith, Christians should see it as much as an opportunity as a threat. The Da Vinci Code will get people talking about Jesus, the Bible, the role of women, and the nature of salvation. This conversation will allow Christians to explain ways in which The Da Vinci Code strays from historical fact and how it reflects careful historical inquiry. More importantly still, it allows Christians to discuss many crucial aspects of Christian faith with those who might otherwise be uninterested.

What follows are seven specific opportunities afforded to Christians by The Da Vinci Code. These don't exhaust the available options, but they are among the most salient ones, in my opinion. These are also the opportunities upon which I plan to focus throughout the rest of this blog series.

Seven Da Vinci Code Opportunities

The Da Vinci Code's claim that the Gnostic gospels present a more accurate picture of Jesus gives us

1. The opportunity to demonstrate the antiquity and reliability of the New Testament gospels, in contrast with the Gnostic gospels.

|

|

| FAQ: What are the Da Vinci Opportunities, as you call them? |

|

The Da Vinci Code's promotion of the Christ of the Gnostic gospels gives us

2. The opportunity to present the engagingly human Jesus of the biblical gospels, in light of which the other-worldly Christ of the Gnostic gospels pales in comparison.

The Da Vinci Code's hailing of Gnostic Christianity gives us

3. The opportunity to show how the orthodox Christian gospel is available and inclusive, in contrast to the esoteric, exclusive message of salvation in Gnosticism.

The Da Vinci Code's claims about Mary Magdalene and women in early Christianity give us

4. The opportunity to explain how the portrait of Mary Magdalene in the New Testament, which does not include her marriage to Jesus, affirms both Mary and women in general, and suggests the full inclusion of women in Christian life.

The Da Vinci Code's claims about the formation of the Christian canon and the involvement of Constantine in this process give us

5. The opportunity to show how the Christian Bible in fact came to be recognized, and why this supports confidence in Scripture.

The Da Vinci Code's claims about the lateness of the belief in the divinity of Jesus give us

6. The opportunity to demonstrate the antiquity of Christian belief in the divinity and humanity of Jesus.

The Da Vinci Code's favoring of Gnosticism gives us

7. The opportunity to showcase the compelling, creation-affirming, hopeful Christian "story" of salvation through Jesus, which stands brilliantly in contrast to the obscure, creation-denying, despairing "story" of Gnostic salvation.

But Haven't These Issues Been Addressed Already?

Seeing this list of opportunities, you might wonder if I'm simply plowing already turned up ground. After all, many "anti Da Vinci Code" books have been published already. So why should I bother to do this series? And why should anybody bother to read it?

I have read three of the books that refute historical claims of The Da Vinci Code. I have examined several others in bookstores, but did not buy them. The three books I've read cover to cover are:

Bart Ehrman, Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code: A Historian Reveals What We Really Know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine (Oxford, 2004).

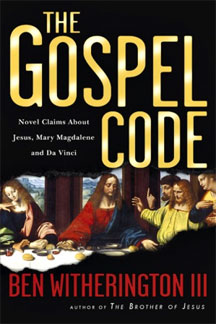

Ben Witherington, The Gospel Code: Novel Claims About Jesus, Mary Magdalene and Da Vinci (InterVarsity, 2004)

| When it comes to the most important points, these books offer basically the same insights and come to basically the same conclusions. My favorite book is the one by Witherington. It's readable, trustworthy, sometimes witty, and sometimes moving. Bock's book tends to be simpler, which may be helpful to some readers. Ehrman's book is good, but every now and then Ehrman lets his undue skepticism about Christian orthodoxy color his otherwise fine discussion. (To be fair, I should say that Bock and Witherington let their orthodox Christian beliefs enter into the conversation as well.) Ehrman's book would be especially good for readers who have a bias against Christians, and who might therefore be dismissive of Bock and Witherington. Ehrman is not a Christian, and has written books critical of orthodox Christianity. (See my long review of Ehrman's recent book, Misquoting Jesus.) Anyone who thinks that only conservative Christians oppose The Da Vinci Code will be proven wrong by Ehrman. |

|

|

Much of what I will say in this blog series will be similar to what you'd find in the books on the subject. I will try to give credit where credit is due as I write. Most of the primary material I know from my own studies, though I picked up many tidbits of wisdom from Bock, Ehrman, and Witherington.

So why do all of this as a blog series? Well, first of all, I can offer my discussion for free. So that must be worth something, though I'd still recommend that you buy and read Witherinton's book, or one of the others. Second, an online examination of The Da Vinci Code will be helpful to people who don't have ready access to one of the books. Third, what I write will be easily searchable. Fourth, I'll be able to link to many pieces of evidence (like primary source material from the Gnostic gospels), so readers who want to investigate the raw data for themselves will be able to easily. Books can't do this. Fifth, if you find yourselves in a conversation with somebody about some aspect of The Da Vinci Code, it will be easier to send this person to my online discussion than to tell somebody to buy a book.

In my next post in this series I will launch my explanation of the first opportunity, which has to do with the reliability of the biblical gospels. (And for those who've been reading my blog for a while, no, I will not repeat my lengthy series on this topic. Just a few highlights!)

Opportunity #1: The Antiquity and Reliability of the New Testament Gospels (Section A)

Part 6 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Monday, March 20, 2006

In my last post in this series I laid out seven opportunities that comprise The Da Vinci Opportunity. Beginning today, I want to take advantage of the first sub-opportunity:

The Da Vinci Code's claim that the Gnostic gospels present a more accurate picture of Jesus gives us

1. The opportunity to demonstrate the antiquity and reliability of the New Testament gospels, in contrast with the Gnostic gospels.

The Gospels According to The Da Vinci Code

| To begin, let me sketch the picture of the gospels painted in The Da Vinci Code, largely by the historian Sir Leigh Teabing. According to this view, Jesus's life had been "recorded by thousands of followers across the land" (p. 231). In fact, when the Christian canon of Scripture was being identified in the fourth century, according to Teabing, "More than eighty gospels were considered for the New Testament," yet only Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were chosen, because they fit the political agenda of Constantine (p. 231). |

|

| FAQ: What does The Da Vinci Code claim to be true about the gospels? |

|

Yet among the rejected gospels were many that were "earlier" than the biblical foursome (p. 234). These gospels contained "the original history of Christ" (p. 234), which was rejected by the official Church and embraced only among those labeled as heretics. Even though Constantine and the Church tried to destroy the non-biblical gospels, which Teabing refers to as the "unaltered gospels" (p. 248), some of them did survive. Here's Teabing's account of this bit of fortuitous history:

"Fortunately for historians," Teabing said, "some of the gospels that Constantine attempted to eradicate managed to survive. The Dead Sea Scrolls were found in the 1950s hidden in a cave near Qumran in the Judean desert. And, of course, the Coptic Scrolls in 1945 at Nag Hammadi. In addition to telling the true Grail story, these documents speak of Christ's ministry in very human terms. Of course, the Vatican, in keeping with their tradition of misinformation, tried very hard to suppress the release of these scrolls. And why wouldn't they? The scrolls highlight glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications, clearly confirming that the modern Bible was complied and edited by men who possess a political agenda—to promote the divinity of the man Jesus Christ and use His influence to solidify their own power base" (p. 234)

Teabing relates one other curious gospel tidbit. Among the mysterious Sangreal documents, which include "thousands of unaltered, pre-Constantine documents, written by the early followers of Jesus, revering Him as a whole human teacher and prophet," is the "legendary "Q" Document—a manuscript that even the Vatican admits they believe exists. Allegedly, it is a book of Jesus' teaching, possibly written in His own hand" (p. 256.

Weeding Out Some Silliness

| Before I deal with the substance of the Brown/Teabing position on the gospels, I want to pull out a few silly weeds. By so doing, I'm not trying to score trivial points. Rather, when you see how much Brown has made up out of thin air when it comes to the details, you may be inclined to take his more substantial claims in the same vein. So, let me list some of Teabing's insights and show why I call them silly. |

|

| FAQ: What are some of the most wildly fictional claims in The Da Vinci Code about the gospels? |

|

1. Jesus's life had been "recorded by thousands of followers across the land."

Comment: There is absolutely no evidence for this. Plus, given that the culture in which Jesus ministered was predominantly oral, not written, it's highly unlikely that many of his followers wrote down what he said and did.

| 2. "More than eighty gospels were considered for the New Testament." |

|

| FAQ: Were "more than eighty gospels considered for the New Testament"? |

|

Comment: There is absolutely no evidence for this. When the canon of the New Testament was identified by the Church, there were only four gospels that were ever taken seriously for inclusion. We have no evidence that eighty gospels ever existed. In the Nag Hammadi Library, for example, there are only four documents with the name "gospel" attached (Truth, Thomas, Philip, and Egyptians; Mary is included in English versions of the Nag Hammadi Libary, but wasn't found there). The Early Christian Writings website, which uses the term gospel quite liberally, and includes most early Christian writings, has only twenty-one so-called "gospels." Even if we add in other documents that record esoteric teachings of the Savior, the total number of "gospels" might be as high as twenty five, if we count generously. In fact, most of the so-called Gnostic gospels are nothing like the biblical gospels, with stories of the human Jesus. Rather, they are collections of His supposed revelations.

|

|

| |

Talk about some serious weeding! (Well, actually, this is my son doing some gleaning in a bean field. I didn't have any weeding pictures.)

|

3. There are gospels among the "Dead Sea Scrolls" that "were found in the 1950s."

Comment: There is absolutely no evidence for this. The Dead Sea Scrolls, many of which were discovered in the 1940s, contain no document anything like a gospel. There are no writings about Jesus in the Scrolls, which are Jewish sectarian writings, most all of which antedate Jesus. A few pseudo-scholarly writers and rogue scholars have seen in the scrolls cryptic references to Jesus, but I don't know of any serious scholar of any theological stripe who believes this.

4. Some gospels can be found among "the Coptic Scrolls" discovered "in 1945 in Nag Hammadi."

Comment: There is evidence for this. Here, at least, Brown has the date right. The Nag Hammadi collection was discovered in 1945. But, also, there were no scrolls in the collection, but only leather-bound papyrus codices (books). Many of the Nag Hammadi do feature Jesus, or better, the Savior, in one fashion or another. Four of the Nag Hammadi tractates are specifically called gospels.

5. The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi Library tractates "speak of Christ's ministry in very human terms."

Comment: Though this is a subjective judgment, there is virtually no evidence for this. As I've already said, the Dead Sea Scrolls don't speak of Christ's ministry at all. And nobody who's ever read the Nag Hammadi Library would describe it as speaking of Christ's ministry in human terms. In fact, the opposite is true. If you don't believe me, thumb through a copy of The Nag Hammadi Library in English and see for yourself. Because the documents in this library are mostly Gnostic in character, they have no interest whatsoever in the human Jesus. In fact, they tend to be dismissive of the human Jesus. I'll say more about this later.

6. The "legendary 'Q' Document," which even the Vatican believes to exist, might well have been written by Jesus Himself.

Comment: Close, but no cigar. "Q" (from the German word Quelle, which means "source") is not legendary, but a scholarly invention which helps to explain the commonalities between Matthew and Luke. There may have been such a document, but nobody really knows. Most scholars who believe in "Q" actually think there were various versions of the document. I'm not aware of any scholar, in the Vatican or otherwise, who believes that "Q" actually exists today, even if it once existed. And I'm not aware of anybody, scholar or not, other than Sir Leigh Teabing, who believes that Jesus might have written "Q."

Let me say, once again, that Brown is writing fiction. I'm not criticizing him for making up this stuff. The silliness of many of Teabing's claims tip off the informed reader that Brown is having some good fun here, but not writing good history. Yet what about the claim that the non-canonical gospels are older than the biblical gospels, and contain "the original history of Christ." I'll address this in my next post.

Opportunity #1: The Antiquity and Reliability of the New Testament Gospels (Section B)

Part 7 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Tuesday, March 21, 2006

In my last post, I began to evaluate The Da Vinci Code's claims about the gospels, both biblical and non-biblical. I showed that several of the statements made by Sir Leigh Teabing, the heavenly revealer in Brown's novel, were downright silly. This is fine in a fictional work, just so long as nobody takes the statements seriously. Unfortunately, as I have shown earlier in this series, many readers take Teabing's fantasies as, well, gospel truth. Hence my critique.

| Yet not all of Teabing's claims about the gospels can be summarily dismissed. In particular, one of his non-silly notions concerns which gospels are the oldest and most reliable sources of information about Jesus. Brown's historian claims that "gospels that spoke of Christ's human traits" were "earlier gospels" than Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. These contained "the original history of Christ" and were embraced, not by orthodox Christians, but by those who were called "heretics." Efforts by Emperor Constantine and the Church to destroy these earlier gospels failed, however. Many of them were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls and in the Nag Hammadi Library. These authentic gospels "highlight glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications" in the canonical foursome (p. 234). |

|

| |

Ian McKellen as Sir Leigh Teabing

|

Three of Teabing's claims here are true:

| 1. The non-canonical gospels were indeed embraced by those who came to be known as heretics (Gnostics and others). There were many non-canonical writings, however, that were orthodox in theology, and were rejected by the so-called heretics. |

|

| FAQ: Are any of Leigh Teabing's supposedly historical claims about the gospels true? |

|

2. Though no gospels appear among the Dead Sea Scrolls, some so-called "gospels" were found among the documents discovered in 1945 in Nag Hammadi, Egypt, though none of these gospels looks like what we find in the New Testament. None of the Nag Hammadi gospels, for example, contains much narrative description of Jesus's life or ministry. They are mostly collections of teachings or revelations from a heavenly savior. None of the Gnostic gospels speaks of "Christ's ministry in very human terms" as Teabing claims. In fact, the opposite is true.

3. There are indeed "glaring historical discrepancies" between the non-canonical gospels and the biblical gospels. Most centrally, many of the non-canonical gospels deny that Christ was actually crucified, while in the biblical gospels this is the apex of the narrative. Consider this passage from The Second Treatise of the Great Seth, a tractate from Nag Hammadi that purports to be a revelation of Christ. (If nothing else, you've gotta love that name, The Second Treatise of the Great Seth. Sure sounds more impressive than The Gospel of Mark.)

"I did not succumb to them as they had planned. But I was not afflicted at all. Those who were there punished me. And I did not die in reality but in appearance, lest I be put to shame by them because these are my kinsfolk. . . . For my death which they think happened, (happened) to them in their error and blindness, since they nailed their man unto their death. . . . Yes, they saw me; they punished me. It was another, their father, who drank the gall and the vinegar; it was not I. They struck me with the reed; it was another, Simon, who bore the cross on his shoulder. It was another upon whom they placed the crown of thorns. But I was rejoicing in the height over all the wealth of the archons and the offspring of their error, of their empty glory. And I was laughing at their ignorance" (55:14-56:19).

There you have it. Christ doesn't suffer. As another is crucified in His place, he laughs. No doubt there is a huge discrepancy here between The Second Treatise of the Great Seth and the biblical gospels, where Jesus Christ truly suffered and died. And, given the fact that the earliest Christian beliefs we can identify, not in the gospels, but in the writings of Paul, were centered in the death of Jesus, things don't look so good for the historical credibility of the Great Seth and his Gnostic counterparts. It's much easier to believe that these texts, influenced by the flesh-denying theology of Gnosticism, were altered to reflect Gnostic bias, rather than that the biblical gospels got the story wrong.

In my next post I'll consider in greater detail Teabing's claim that the non-canonical gospels were written before the biblical versions.

Opportunity #1: The Antiquity and Reliability of the New Testament Gospels (Section C)

Part 8 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Wednesday, March 22, 2006

In my last post I continued my scrutiny of the claims made about the gospels by the fictitious historian Sir Leigh Teabing in The Da Vinci Code. In this post I want to consider in greater detail the question of the dating of the gospels.

The Dating of the Gospels

| The Da Vinci Code claims that the "glaring historical discrepancies" between the biblical gospels and the non-canonical gospels weigh in favor of the non-canonicals. Why? Largely because these writings are said to be earlier and thus closer to the real Jesus. Yet, with one possible exception, this claim is as fictional as the notion that Robert Langdon is a professor of symbology at Harvard. (Well, who knows? Prof. Langdon does have his own website!) |

|

| FAQ: When were the gospels written? Are the non-canonical gospels older than the biblical gospels? |

|

In many cases, the dating of ancient documents is perilous business. It's far more of a fine art than a hard science. This is especially true when it comes to the early Christian gospels, biblical and extra-biblical. These writings do not come with dates. Rarely do they refer to historical events or personages that allow us to discern when they were written. For the most part, the manuscripts we have of these documents are at least a century later than the actual writing, so they provide little help when it comes to dating. Generally, the most solid evidence we have for dating early Christian gospels comes from when they are mentioned or quoted by other writers whose literary efforts can be definitively dated. So, for example, Irenaeus of Lyons, writing in about 180 A.D., mentions Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John by name, so we can be sure they were written before this time.

The issues surrounding the dating of the gospels are legion. (Sometimes one wishes these debates could be cast into a herd of pigs of drowned in the Sea of Galilee.) For most gospels, canonical and not, you'll find a range, sometimes a wide range, of possible dates proposed by scholars. The Gospel of Thomas, for example, has proponents of a composition date as early as the 50's A.D., and as late as the mid-second century or even later. Yet, in most cases, a general consensus among scholars exists, even across lines of personal ideology. So, for example, most New Testament scholars would date the writing of the Gospel of Mark to around 70 A.D. no matter what their personal beliefs about Jesus. The other canonical gospels are usually thought to have been written in the next couple of decades (though you'll find a few who argue for earlier dates, and a few who support later dates). (I've gone into this in greater depth in my series, Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?)

The vast majority of scholars agree that the non-canonical gospels, with the possible exception of the Gospel of Thomas, were written well after Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Because many of the extra-biblical gospels depend upon the text of the biblical gospels and other writings, and because they reflect the issues and theological tendencies of the second-century or later, the non-canonical gospels were written, for the most part, at least two generations after the biblical books, and often much more.

The Dating of "The Da Vinci Two"

This is especially and undeniably true for the two Gnostic gospels actually mentioned in The Da Vinci Code, upon which the case for Jesus's marriage to Mary Magdalene rests. The Gospel of Mary (Magdalene) (p. 247) comes from the second century A.D., as is evident by its Gnostic themes and its apparent tension with the orthodox Church. The Gospel of Philip (p. 246) is usually dated in the late second or early third century. It is one of the last of the so-called "gospels."

| This means that the two documents which Leigh Teabing uses to prove the marriage of Jesus to Mary Magdalene are much, much later than the New Testament gospels. No serious scholar, besides Teabing himself, of course, would deny this. If one believes, as is usually but not necessarily true, that an older source is more reliable than a later one, then the facts weigh strongly against Teabing's case. If you are looking for "the original history of Christ," you'd best start with Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John (and maybe Thomas). If there are "glaring historical discrepancies" between these biblical gospels and their non-canonical competitors, then the biblical versions win the historical competition. (Of course it's always possible that the non-canonical gospels contain authentic traditions about Jesus, some of which are not found in the biblical gospels. But, for the most part, the non-canonical texts help us understand early Christian history, but not the life and teaching of the real Jesus.) |

|

| |

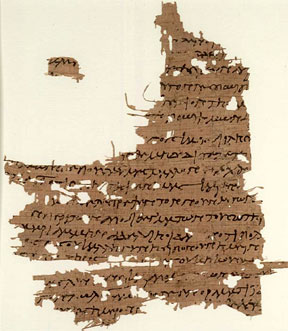

This is a second-century papyrus fragment of the Gsopel of Mary. It's technical label is P.Oxy. L 3525. |

You may have noticed that I have qualified my argument about the lateness of the non-canonical gospels when it comes to The Gospel of Thomas. There are credible scholars today who would date the writing of this gospel in the first-century A.D. A few have even tried to make the case that it was written prior to the biblical gospels. You'll find this argument especially among fellows from the Jesus Seminar.

So what about The Gospel of Thomas? Does it strengthen Teabing's case? I'll tackle these questions in my next post.

Opportunity #1: The Antiquity and Reliability of the New Testament Gospels (Section D)

Part 9 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Thursday, March 23, 2006

In my last post I explained that, almost without exception, the non-canonical gospels, sometimes called "Gnostic gospels," were written decades after the New Testament gospels. On the basis of dating alone, therefore, we would be wise to accept the biblical picture of Jesus as more historically accurate than that found in the non-canonical gospels. But I qualified my comments about the lateness of the non-canonical gospels when it comes to the Gospel of Thomas. In this post I want to address issues having to do with the date of this elusive gospel, and with its relevance for The Da Vinci Code. (To peruse or read this gospel, check it out online.)

When Was the Gospel of Thomas Written?

Few questions in scholarship divide the house more than the question of the date for Thomas. Some scholars date the writing of this gospel to within a couple decades of Jesus's death. Others put the writing in the latter portion of the second century, almost 150 years later. Most scholars, however, see the date of composition somewhere between these extremes. This scholarly majority falls into two basic camps. Camp 1 sees Thomas as independent from the biblical gospels and written in the latter half of the first century (more or less contemporaneous with the New Testament gospels). Camp 2 sees Thomas as reflecting a knowledge of the biblical gospels and other New Testament writings, and therefore written in the second century, where it seems more at home theologically. The debate between these two camps has been going on for more than three decades, and isn't over yet. The evidence for any theory of dating is relatively meager and open to a variety of interpretations. |

|

| |

This is the last part of the Gospel of Thomas from the Nag Hammadi Library. |

I lean in the direction Camp 2, as do the majority of scholars (as near as I can tell). My reasons are:

1. It seems to me that the case for dependence of Thomas on the New Testament is strong, though not watertight.

2. The Gnostic worldview assumed by Thomas seems better suited to a second- than a first-century milieu.

3. The Gnostic theology of "Jesus" in Thomas seems far removed from the man who surely was, among other things, a Jewish prophet. This is especially true of Thomas's non-apocalyptic rendering of the kingdom of God, as well as its preoccupation with self-knowledge.

4. The earliest reference to Thomas comes from Hippolytus, who mentioned it somewhere around 225 A.D. This would suggest that the gospel was written later than the canonical gospels, which are mentioned by second-century writers. (Of course Thomas may have been kept secret for a long time, so it could have been written earlier and simply never mentioned. Or it was mentioned in writings we don't have today.)

5. Thomas's lack of interest in the cross or resurrection of Jesus is inconsistent with everything we know about earliest Christianity (from Paul's letters), and finds a happier home in the second century.

Even if the Gospel of Thomas was written in the second century, it still shows considerable independence from the New Testament gospels. It reflects an awareness of sources (written? oral?) besides the biblical texts, and some of these sources may have contained genuine sayings of Jesus that are not found in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

Ironically, those who argue for an independent and early Thomas are often those who discount the historical reliability of the canonical gospels. But I would make the opposite case. If Thomas is indeed from the first century, and if it is indeed independent of the canonical gospels, then Thomas actually underscores the basic reliability of the canonical gospels in many ways. If you read through the Gospel of Thomas, you'll find much that sounds odd (Gnostic, usually) and much that sounds familiar because it closely parallels the New Testament gospels.

Thomas and The Da Vinci Code

| For the sake of argument, let's assume that Thomas was written in the first century, and that it is independent of the New Testament gospels. How does this impact the case presented by Sir Leigh Teabing in The Da Vinci Code? |

|

| FAQ: Is the Gospel of Thomas relevant to The Da Vinci Code? If so, how? |

|

In fact, the Gospel of Thomas undermines Teabing's case. So the more it is believed to be older and more authentic, the less believable the Teabing/Brown thesis becomes. Let me explain.

First of all, Mary Magdalene is mentioned only twice in this gospel. Here are the passages:

(21) Mary said to Jesus, "Whom are your disciples like?" He said, "They are like children who have settled in a field which is not theirs.

(114) Simon Peter said to him, "Let Mary leave us, for women are not worthy of life." Jesus said, "I myself shall lead her in order to make her male, so that she too may become a living spirit resembling you males. For every woman who will make herself male will enter the kingdom of heaven."

Notice, there is nothing here whatsoever to suggest that Mary was anything more than one of Jesus's follower. There's not the slightest hint of a special relationship between Jesus and Mary, let alone a marriage. So the oldest of the non-canonical gospels provides not a shred of evidence for the thesis that Jesus was married.

Second, if you look again at the second passage I quoted above (saying 114), you'll notice that this isn't exactly conducive to the kind of sacred feminine religion touted by Teabing and celebrated throughout The Da Vinci Code. Of course Peter's snub of women could be rejected as evidence of orthodoxy's devaluing of women. (I'm not saying I believe this, only that this is a move commonly made.) But, though Jesus values Mary, he will help her to become male, so that she can become a living spirit and enter the kingdom of heaven. Maleness in the Gospel of Thomas is equated with being on the "in"; femaleness is excluded from the kingdom of God. It's hard to imagine a less positive passage concerning women and religion. Nothing said by Jesus in the canonical gospels is so negative about women. In fact Jesus accepts real women as women, and lets them learn from him and deliver the message of his resurrection. He didn't lead any of them to become male, and never suggested that this was necessary.

So, ironically enough, what is likely the oldest of the non-canonical gospels not only doesn't support Teabing's case for a marriage between Jesus and Mary, but it also weighs heavily against the idea that the Gnostic gospels are friendly to women and the divine feminine. Other passages in the Nag Hammadi Library are more positive, to be sure, but at best Gnosticism offers inconsistent encouragement to women, unless they are happy about the idea of becoming male in a spiritual sense.

Through this and other recent posts, I've been talking consistently about Gnosticism. Though some of my readers probably have a good idea what Gnosticism was, others have only a foggy notion of what I'm talking about. So in my next post I'll offer a quick summary of what Gnosticism was (and is).

Excursus: What is Gnosticism?

Part 10 of series: The Da Vinci Opportunity

Posted for Friday, March 24, 2006

Throughout this series on The Da Vinci Opportunity I have been speaking of Gnosticism. This is necessary because, though The Da Vinci Code doesn't discuss Gnosticism directly, it does draw from Gnostic writings, and it does speak favorably of the gospels generally known as Gnostic. Before I go further in this series, I want to put up a brief overview of Gnosticism. If you're already familiar with this subject, you can check to see if I've done an adequate job. (If not, please e-mail me with your suggestions.) But if your notion of Gnosticism is rather foggy, let me reveal the truth (Gk. gnosis) about Gnosticism.

Gnosticism is the modern term used to refer to a religious and philosophical movement that originated in the first or second century A.D., that was especially strong in the second and third centuries A.D. and that was considered heretical by the majority of Christians at that time as well as the majority of pagan bearers of the Platonic philosophical traditions (i.e., Neo-Platonists). The ancients often referred to the people of this movement as Gnostics (gnostikoi). The movement, which was not a single, monolithic social-theological reality, emphasized at its core a special claim to special gnosis (gnosis, knowledge); thus the terms Gnostics and Gnosticism. Until the discovery in 1945 of a large group of texts near Nag Hammadi, Egypt, most of our knowledge of the ancient Gnostics came from their opponents. With the Nag Hammadi texts (usually designated NHC, Nag Hammadi Codices [Books]), which were made available to the public between 1956 and 1977 and most of which can be identified as Gnostic writings, we have for the first time in our modern period the opportunity to understand Gnostics on their own terms. (p. 400).

If you're unfamiliar with Gnosticism, I'd urge you to read this definition again. Seriously. It will help you grasp what Gnosticism is really all about.

Since we have very little knowledge of actual Gnostic communities, it's hard to say much about how Gnostic people actually lived. Sociological analysis of Gnostic documents can offer some suggestions, but these are more speculative than solid. Yet the fundamental feature of Gnostic belief, which surely influenced Gnostic practice, is a profound dualism that affirms the goodness of spirit and the badness of matter. The physical world, from the Gnostic point of view, is evil. In fact, it was created not by the one true God, as in Christian belief, but by some junior, wannabe god. This god messed up big time, creating something that shouldn't have been made in the first place, and that needs to be transcended if an individual wants to experience salvation. Because they considered matter, including physical bodies, to be fundamentally evil, it's likely that most Gnostics were also ascetics (denying bodily pleasures). Christian opponents sometimes accused Gnostics of being libertines (engaging excessively in bodily pleasures), and some might have been. But a body-denying ethos pervades most of Gnosticism, and suggests an ascetic denial of human existence.

Although Gnostics believed that matter, including human bodies, was evil, they did not think human beings were without hope. Imbedded within people, or at least some special people, was the spark of the divine, a tiny bit of the real God. Thus salvation involved receiving revealed knowledge (gnosis) of the fact that one had divinity buried within oneself. This knowledge, when believed, allowed a person to transcend the evil world, and ultimately to return to the good God. Whereas orthodox Christianity held that sin (rebellion against God) was the fundamental human problem, Gnostics believed that ignorance was that basic problem.

Since matter was basically evil, from the Gnostic point of view, the redeemer was often seen as something other than human. Many Gnostics believed that Jesus the man was not the same as Christ the revealer. Moreover, since salvation required the revelation of knowledge, not atonement for sin, Gnostics had no place for the death of the Savior by crucifixion. In many Gnostic writings the real Christ is not crucified, but stands nearby laughing when Jesus is killed. |

|

| |

The Jewish sectarian community at Qumran along the Dead Sea had ascetic tendencies. World-denying folk often live in desolate places, like Qumran or the Egyptian desert.

|

The Gnostic system makes sense. I'm not saying I believe it, of course. But it has its own internal logic. Yet this logic leads to elitism, because only certain, special people have the knowledge required for salvation. It also leads to a world-denying life. You would not find in Gnosticism a philosophical basis for making a difference in the world. Issues of justice have to do with the evil world that Gnostics must transcend, not transform. Unlike Jews and Christians, Gnostics have no hope of a renewed world, a new creation yet to come. Rather, they hope to escape this world through their special knowledge of their own divinity. Thus Gnosticism is not only world denying, but also individualistic. One does not find in the Gnostic writings a concern for building a community of believers, though there may well have been such communities. I believe that early Gnosticism died out, not only because it was opposed by orthodox Christianity, but also because its vision was simply too individualistic and other-worldly to sustain a thriving religious tradition.

In many ways, however, Gnosticism has been making a comeback. In my next post in this series I want to say something about the popularity of Gnosticism today, which has surely influenced Dan Brown in his writing of The Da Vinci Code.

To continue with Part 11 of The Da Vinci Opportunity, click here.

|