| |

A Resource by Mark D. Roberts |

|

The Bible, the Qur'an, Bart Ehrman, and the Words of God

A Conversation about the Pope, the Bible, the Qur'an (Quran, Koran),

God, Inspiration, and Bart Ehrman's Misquoting Jesus.

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2006 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com. Thank you.

Did the Pope Get It Right?

Part 1 in the series: The Bible, the Qur'an, Bart Ehrman, and the Words of God

Posted for Tuesday, January 10, 2006

| Once again I'm going to post on this website my answer to a question posed by Hugh Hewitt on OneTrueGodBlog.com. I'm doing this because: 1) I think this material will be interesting to readers of markdroberts.com and because 2) I don't have time to write two posts tonight. I would encourage you to visit OneTrueGodBlog.com in time to see what the other respondents have to say. |

Hugh has asked us to comment on an interview he did with Father Joseph Fessio, the Provost of Ave Maria University, and a former student and confidant of Pope Benedict XVI. Hugh is especially interested in our response to sections of the interview that address the contrast between the Muslim Qur'an (sometimes spelled Koran) and the Christian Bible.

I'm going to assume that you haven't read the interview in full, since it's almost 5,000 words long. So I'll describe the context for the material of interest to Hugh, and then quote from Father Fessio, along with a bit of added dialogue with Hugh. This will take up a few hundreds words, but it will be shorter than the whole interview. (By the way, I would recommend that you read the whole interview, because it's both fascinating and relevant, in many ways.)

The context for the sections of greatest interest to Hugh was a conversation about Isalm in the world of today and the future, especially in Europe, where the Muslim population is quickly overtaking the non-Muslim (Christian, secular) population. Father Fessio is not alone among many sober scholars who forsee a Muslim Europe in the not-too-distant future. He and Hugh were talking about the potential for Isalm to enter into serious and mutually-respectful dialogue with the modern, Western world. Father Fessio referred to a Muslim scholar who believes this possible, only if Islam is willing to be open to a reinterpretation of the Qur'an. |

|

| |

Father Joseph Fessio (right) with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the man who would be Pope.

|

At this point in the interview Father Fessio related a fascinating story about Pope Benedict XVI, who was conversing with some of his students and friends in his summer home at Castel Gandolfo. When somebody mentioned this idea of Isalm reinterpreting the Qur'an for today's world, the Pope made a spontaneous little speech, which was summarized in the interview by Father Fessio. Here is the Father's summary (not the actual words of the Pope, mind you, but a summary by one who knows his thought well):

There's a fundamental problem with [Isalm reinterpreting the Qur'an for today], because he said in the Islamic tradition, God has given His Word to Muhammad, but it's an eternal Word. It's not Muhammad's word. It's there for eternity, the way it is. There's no possibility of adapting it or interpreting it, whereas in Christianity, and Judaism, the dynamism's completely different: that God has worked through His creatures. And so, it is not just the Word of God, it's the word of Isaiah, not just the Word of God, but the word of Mark. He's used His human creatures, and inspired them to speak His word to the world. And therefore by establishing a Church in which he gives authority to His followers to carry on the tradition and interpret it, there's an inner logic to the Christian Bible, which permits it and requires it to be adapted and applied to new situations. I was . . . I mean, Hugh, I wish I could say it as clearly and as beautifully as he did, but that's why he's Pope and I'm not, okay? That's one of the reasons. One of others, but his seeing that distinction when the Qur'an, which is seen as something dropped out of Heaven, which cannot be adapted or applied, even, and the Bible, which is a Word of God that comes through a human community, it was stunning.

After this, Hugh followed up with a couple of questions:

HH: And so, is it fair to describe [the Pope] as a pessimist about the prospect of modernity truly engaging Islam in the way modernity has engaged Christianity?

JF: Well, the other way around.

HH: Yes. I meant that.

JF: Yeah, that Christianity can engage modernity just like it did . . . the Jews did to Egypt, or Christians did to Greece, because we can take what's good there, and we can elevate it through the revelation of Christ in the Bible. But Islam is stuck. It's stuck with a text that cannot be adapted, or even be interpreted properly.

HH: And so the Pope is a pessimist about that changing, because it would require a radical reinterpretation of what the Koran is?

JF: Yeah, which is it's impossible, because it's against the very nature of the Koran, as it's understood by Muslims.

There seem to be three major questions here:

1. Has the Pope, as summarized by Father Fessio, correctly represented the Islamic understanding of the Qur'an?

2. Has the Pope, as summarized by Father Fessio, correctly represented the Christian understanding of the Bible?

3. Is, therefore, the distinction claimed by the Pope between the Islamic understanding of the Qur'an and the Christian understanding of the Bible in fact true and accurately portrayed?

I will attempt to answer these questions. But first a word of confession: I'm not an expert by any means on Islam, though I studied it with an Islamic expert in grad school, and have read a couple of books on Isalm since them. I'm quite sure that Pope Benedict's understanding of Isalm is far more extensive and informed than mine. Nevertheless, I'll weigh in on these issues.

Question #1: Has the Pope, as summarized by Father Fessio, correctly represented the Islamic understanding of the Qur'an?

In a nutshell, yes, he has. No surprise here. Muslims believe, not only that the Qur'an is the Word of God (Allah = God in Arabic) as a whole, but also that the words of the Qur'an are the literal words of God. These words, according to Islamic doctrine, were revealed to the Prophet Muhammad over the course of many years by the angel Jabril (Gabriel). They were fully and correctly received and recited (Qur'an means "recitation") by Muhammad, and then written down by Muhammad's colleagues, since the Prophet himself couldn't read or write.

Muslims believe that after Muhammad's death, a scribe collected the manuscripts of the Qur'an that had been written during the Prophet's life. He was assisted by many others who had memorized the recitations, so a definitive text of the Qur'an was made, from which all other copies are derived. This means that Muslims can claim to have, not only the exact words of Muhammad, but also the exact words of God. According to the helpful discussion on the Muslim website, IslamOnline.net:

Thus, the Qur’an remains today exactly as it was revealed more than 14 centuries ago and contains the exact Words of Allah. Many thousands of Muslims memorized it each generation so that it was never forgotten. Further, the Arabic language in which the Qur’an was revealed remains a living language. There are copies of the Qur’an from the first century after the revelation in libraries in the Muslim world. A comparison to modern printed copies shows that the Qur’an has not changed over the centuries.

Thus Muslims revere the Qur'an in a way that reminds me of how Christians revere Jesus, whom we believe to be the Word of God Incarnate. Though they do not worship the Qur'an, they believe it to be divine in the highest possible sense. This explains features of Muslim piety that we Westerners might not understand.

For one thing, it explains why Muslims believe that the Qur'an cannot truly be translated into any other language. Since translation inevitably changes meaning to some extent, and since God chose to speak in Arabic, one only has the real Qur'an when one knows Arabic. Translations are, at best, interpretations.

Muslim regard for the actual words of the Qur'an also explains why many memorize the entire holy book in Arabic, even those for whom Arabic is not their native tongue. This is an impressive feat, given that the length of the Qur'an is roughly similar to that of the New Testament.

Akbar S. Ahmad, a world-renowned Isalmic scholar, describes Muslim reverence for the Qur'an in this way in his insightful book, Islam Today:

For Muslims the Quran is a source of guidance and inspiration. They revere it as the word of God and place it, usually wrapped in clean cloth, on a high place in the room. Out of respect they will not point their feet at it or leave it lying on the floor. In traditional society it is still used to administer oaths and to be chanted as part of the cure for illness. Its recitation is therapeutic to Muslims, who derive comfort and strength from it. (p. 32)

(Note: Ahmad's book is both an explanation of and an apologetic for Isalm.)

More information on the Qur'an from a faithful Muslim perspective can be found at Quran.ork.uk. IslamOnline has the Qur'an available in three different English translations. There are lots of articles on the Quran at the Isalm for Today website. This link will also allow you to hear a portion of the Qur'an being chanted.)

You can already see differences between Muslim regard for the Qur'an and Christian respect for the Bible. Even those of us who believe that the Bible is God's Word in a very strong sense do not protect it in a clean cloth or make sure we don't point our feet in its direction.

In my next post I'll try to summarize Christian views on the way in which the Bible is God's Word (or words).

The Bible as God's Word . . . and Words? Section A

Part 2 in the series: The Bible, the Qur'an, Bart Ehrman, and the Words of God

Posted for Wednesday, January 11, 2006

In yesterday's post I began to respond to a request from Hugh Hewitt on OneTrueGodBlog.com. Hugh asked me, and the other writers for this website, to comment on an interview he had with Father Joseph Fessio, a Catholic theologian and, more importantly, a confidant of Pope Benedict XVI. In this interview Father Fessio summarized some comments by the Pope on the Bible and the Muslim Qur'an, in which he highlighted different understandings of their divine nature.

Yesterday I quoted from Hugh's interview and commented on the Pope's understanding of how Muslims view the Qur'an. Today I'm going to begin to summarize and evaluate what the Pope, in the summary of Father Fessio, said about the Christian Bible. In order to do this, I will, once again, quote what Father Fessio said as he reported what Pope Benedict shared with some of his former students in his summer house in Castel Gandolfo, Italy. I will italicize the parts of this quotation that address the Bible.

There's a fundamental problem with [Isalm reinterpreting the Qur'an for today], because he said in the Islamic tradition, God has given His Word to Muhammad, but it's an eternal Word. It's not Muhammad's word. It's there for eternity, the way it is. There's no possibility of adapting it or interpreting it, whereas in Christianity, and Judaism, the dynamism's completely different: that God has worked through His creatures. And so, it is not just the Word of God, it's the word of Isaiah, not just the Word of God, but the word of Mark. He's used His human creatures, and inspired them to speak His word to the world. And therefore by establishing a Church in which he gives authority to His followers to carry on the tradition and interpret it, there's an inner logic to the Christian Bible, which permits it and requires it to be adapted and applied to new situations. I was . . . I mean, Hugh, I wish I could say it as clearly and as beautifully as he did, but that's why he's Pope and I'm not, okay? That's one of the reasons. One of others, but his seeing that distinction when the Qur'an, which is seen as something dropped out of Heaven, which cannot be adapted or applied, even, and the Bible, which is a Word of God that comes through a human community, it was stunning.

Has the Pope, as summarized by Father Fessio, correctly represented the Christian understanding of the Bible?

The wording of my question here has a fundamental flaw. I refer to "the Christian understanding of the Bible," as if there were one Christian viewpoint. In fact there are thousands of Christian understandings of the Bible. Even within the Reformed, evangelical tradition, which is my theological home, there is no consensus about the details of biblical inspiration and authority. Yet, having said this, I would observe that the Pope gets it bascially right.

Indeed, there are some Christians who believe that the Bible is not only the Word of God, but also that it comprises the actual words of God that were dictated to the human writers of Scripture. Yet this is the minority perspective, even among evangelical Christians who have what we call a "high" view of scriptural authority. Consider the "Statement of Faith" of the National Association of Evangelicals, for example. About the Bible it states: "We believe the Bible to be the inspired, the only infallible, authoritative Word of God." Some who affirm this truth would argue that the actual words of the Bible are, of necessity, God's own words. But many would stop short of that affirmation, agreeing with the Pope that the words of Scripture have dual authorship, if you will. They are inspired by God, and yet they are also the words of the human writers. Thus, most conservative Christians believe in the verbal inspiration of Scripture, that God inspired the words used by the biblical writers, without denying that the writers themselves contributed in this process as well. The words of Scripture are inspired, but not dictated. (For a helpful overview of these issues, see this post on the bible.org website.)

No doubt it's much simpler to affirm, as Muslims do, that one's holy book is 100% the actual words of God. It's also easier to affirm, as many liberal Christian do, that the Bible is inspired by God in some lesser sense, but that it is first and foremost a human book, filled with errors and cultural limitations as well as spiritual insights. It's much messier to believe, as most conservative, orthodox Christians of all theological stripes believe, that the Bible is truly God's Word, and that it is also a human book, with words chosen by human authors, and that somehow the Holy Spirit guided a mysterious process that inspired the biblical writers, kept them from doctrinal error, and yet allowed them to write in their own styles and words.

Yet this messiness makes sense of the Bible as we have it. Surely some portions of Scripture sound as if they may have been dictated from heaven, such as: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God" (John 1:1) And there are prophetic passages in which the prophet speaks the actual words of God, beginning with "Thus saith the Lord." Yet other passages have a much more human ring. In 1 Corinthians, for example, as Paul is remembering his ministry in Corinth, he writes,

I thank God that I baptized none of you except Crispus and Gaius, so that no one can say that you were baptized in my name. (I did baptize also the household of Stephanas; beyond that, I do not know whether I baptized anyone else. (1 Cor 1:14-16)

One might very well see the hand of the Spirit here, keeping Paul from writing error. But it would seem odd to attribute to God the precise words of "I do not know whether I baptized anyone else."

| You might wonder how it is possible for the Bible to be God's Word in a strong sense, yet for the words of the Bible to be something other than dictated by the Holy Spirit. Let me provide a simple and rough analogy to help explain this. Suppose God Himself transported me to heaven and showed me the most beautiful sapphire ever created. As I gazed at this gem, suppose God said to me, "Now your task is to describe this sapphire to human beings." So I come back to earth, and set about the business of doing what God commanded me. I might describe the sapphire as deep blue, or maybe as cerulean, or perhaps as blue as the night sky, or . . . . Any of these descriptions would be true. All would reflect genuine revelation. Yet the choice of words would be my own. Of course the actual process of biblical revelation is far more complex than this, I gladly admit. But you can at least see how genuine divine revelation could also be matched with human choicefulness about words. When I say, "The sapphire was deeper blue than the deepest ocean," I'm speaking the truth, yet in my own words. (Most Christians would add to this analogy the notion that the Holy Spirit would keep me from saying that the sapphire was green. And many would also add the the Spirit helped me in my choice of the words to use to describe the sapphire.) |

|

| |

This is the Star of Bombay, a sapphire weighing in at 182 carets. It's in the Smithsonian Museum.

|

Tomorrow I'll finish up this conversation about the Bible as God Word/words.

The Bible as God's Word . . . and Words? Section B

Part 3 in the series: The Bible, the Qur'an, Bart Ehrman, and the Words of God

Posted for Thursday, January 12, 2006

In my last post I began to talk about how Christians view the Bible. In particular, I explained how most orthodox Christians believe the Bible is God's Word, yet without believing that every particular word in the Bible was dictated by God. Instead, a mysterious, blessed interaction of the divine and the human led to the writing, editing, and collecting of the books that are in the Christian Bible.

If you follow theological conversations very much, you know that Christians have been arguing over the particulars of biblical inspiration for a long, long time, and that this argument is still going on. Rather than getting too worked up about this the nuances of this argument, however, I have tried instead to stick with what Scripture clearly teaches about itself. Perhaps the clearest passage in this regard comes from 2 Timothy 3:14-17. Here Paul writes says to Timothy:

But as for you, continue in what you have learned and firmly believed, knowing from whom you learned it, and how from childhood you have known the sacred writings that are able to instruct you for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus. All scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, so that everyone who belongs to God may be proficient, equipped for every good work.

This text specifies that "all scripture" is "inspired by God." It does not explain the process of inspiration or the way in which inspiration allows for a genuine human component. Rather, the passage focuses on the usefulness of Scripture, "for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness." Moreover, this passage makes it clear that the primary purpose of Scripture is to lead one to "salvation through faith in Christ Jesus." Though Christians will differ on the details, I believe that every Christian should affirm what we find in this passage from 2 Timothy, and that believing this will give us plenty to go on for our faith and practice as believers. It means we trust the Bible to bring us to faith in Christ, and to train us in godly living. We are not free to disregard Scripture, or to reject as less-than-inspired those passages that we don't like. Yet, at the same time, we have the responsibility of translating and applying Scripture in cultures far different from those in which the biblical books were penned.

Part of what makes the discussion of Scripture complicated for Christians, apart from the mysteries of divine inspiration, is the fact that we believe the Word of God came to earth in a form different from the Bible. In fact, the primary coming of God's Word on earth was not in writing at all, but in the person of Jesus Christ, the Word of God incarnate (John 1:14). Jesus, we believe, was the perfect and complete reality of God on earth. The Bible, however inspired and authoritative it may be, is never thought to be as fully divine as Jesus was, or at least it should never be thought of this way by Christians. Though we revere the Bible, we do not worship it.

Thus, no matter how marvelously inspired Scripture may be, it assumes a kind of secondary status as God's Word on earth, subordinate to the primary incarnation of the Word in Jesus Christ. This means, among other things, that we don't need every word of the Bible to be God's perfect, dictated word, because we believe the one and only perfect Word has come once and for all in Christ.

This does not mean, however, that Christians have the freedom to disregard biblical teaching. You'll notice that the Pope did not suggest this. Rather, he stated, in the summary of Father Fessio, that the Bible can and must be "adapted and applied to new situations." This adaptation does not allow for changing the text or disregarding portions of it. It does, however, permit and even encourage the translation of the Bible into new languages, something Muslims are reticent to do with the Qur'an. It also means that we Christians need to discover, with the help of the Holy Spirit working in the Christian community, what it means to obey biblical teaching in a world that's very different from the one in which the Bible was first written.

In saying that the Bible is the Word of God, but that the individual words were not all dictated verbatim by the Holy Spirit, I'm not suggesting that the actual words of the Bible don't matter. In fact they do, because ideas don't come apart from words. Believing that the biblical writers were inspired by the Spirit, and that the Spirit guided and limited their choice of words, and that the writers themselves selected their words carefully, I would argue that the actual words matter a great deal if we want to understand God's written revelation. And, yes, I also believe that there is great value in knowing the languages in which the Bible was written, even though I think translation is both necessary and fine. After all, I spent years of my life studying Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic, and I've taught Greek in seminary. I've also practiced and taught exegesis, much of which has to do with the precise meanings of words. So the words of the Bible do matter, and are worthy of careful study and humble interpretation. Nevertheless, I do not believe that God dictated every word of the Bible in the way Muslims believe Allah revealed His words to Muhammad through the angel Gabriel.

For Christians, the Bible is a sacred book. But we do not treat actual Bibles with the same sort of reverence that Muslims offer to the Qur'an. We aren't scandalized if a Bible touches the floor. And we aren't concerned if our feet point in the direction of a Bible on our bookshelf. Moreover, though many of us memorize Bible verses, most of us do not seek to memorize the whole of the Bible, especially not in the original languages.

For us, the Bible is the Word of God in writing, and thus it deserves our respect and obedience. Yet the most important task of the written Word of God is to bear witness to and lead us to Jesus Christ, the Word of God incarnate. Our allegiance to and reverence for Christ take precedence over our allegiance to and reverence for the Bible, even though we come to know Christ through the Bible.

In my discussion of the Qur'an in Part 1 of this series I referred to the Muslim belief that the original text of the Qur'an has been passed down perfectly through the Islamic scribal tradition. Not all scholars of Islam believe that this is true, however. Nevertheless, the situation with the Christian Bible is more complicated. In fact, the way in which the writings of the New Testament have been passed down has led to a recent controversy. To this I'll turn in my next post. |

|

| |

This is Bibleman, whose faith in Christ gives him superhuman powers, not to mention the full armor of God. Bibleman, who fights against evil, was created by Christians. It's impossible to imagine any serious Muslim coming up with Qur'anman, and thinking that this would somehow be honoring to God. Christians have a freedom with respect to Scripture than Muslims do not experience.

|

Do We Even Have the Bible God Inspired?

Part 4 in the series: The Bible, the Qur'an, Bart Ehrman, and the Words of God

Posted for Friday, January 13, 2006

In my last two posts I outlined a basic, orthodox Christian understanding of the way in which the Bible is God's Word. We believe that the Bible has been inspired by God, and that this inspiration has impacted the actual words of Scripture, but not that these words were dictated by God to the writers of the biblical documents. We also believe that these authors contributed to the writing of the Bible in a mysterious interaction between the divine and human. Nevertheless, the result has produced writings that truly reveal God to us and teach us how we are to live. Thus Scripture is authoritative in a unique way. Its teachings, when rightly interpreted and applied, show us both what to believe and how to act.

Muslims have similar confidence in their holy book, the Qur'an. Yet they regard the actual words of the Qur'an as the very words of Allah (God in Arabic). The Prophet Muhammad had no role in the formation of these words, according to classic Islam. He simply passed on what the angel Gabriel told him, verbatim.

Muslims believe that they have access to the very words of God today because the recitations of the Prophet were accurately recorded during his lifetime, and then accurately collected and edited after his death. Although non-Muslim scholars would dispute this, Muslims are convinced that their copies of the Qur'an, as long as they are in the original Arabic and not in translation, preserve the very words of God. Thus they put their full confidence in the Qur'an, and revere it as a holy book.

Christians, even very conservative ones, do not have the same assurance regarding the passing on of the biblical texts. We believe that the texts from which we get our Scripture were passed on through a process of copying and recopying, and that sometimes this process wasn't perfect. Thus Christians who believe in the inerrancy of Scripture, for example, often quality this belief by saying that only the original autographs (the original writings by the original authors) are, strictly speaking, without error. The classic Chicago Statement of Biblical Inerrancy states,

We affirm that inspiration, strictly speaking, applies only to the autographic text of Scripture, which in the providence of God can be ascertained from available manuscripts with great accuracy. We further affirm that copies and translations of Scripture are the Word of God to the extent that they faithfully represent the original. We deny that any essential element of the Christian faith is affected by the absence of the autographs. We further deny that this absence renders the assertion of Biblical inerrancy invalid or irrelevant. (Article X)

According to this Statement, only the original manuscripts are absolutely inerrant. But the process of transmission, however imperfect, is reliable enough to "faithfully represent the original," such that no "essential element of the Christian faith" is compromised by the lack of original autographs. I have gone on record as agreeing with this affirmation, believing that the extant manuscripts of the Bible, as interpreted through the discipline of text criticism, allow us to have a high degree of confidence that the Bible we read is virtually identical to what was originally penned.

But a recent publication by a New Testament scholar has challenged this confidence, and this book is getting a lot of attention from the secular press (including, for example, an interview on NPR). Bart Ehrman, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has written Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. With a title like this, a book is sure to get lots of attention, even though the book itself has very little to say about the statements of Jesus. The title is about hype and selling books, not substance.

Ehrman's book has many positive qualities. It is a readable and informative introduction to the history of the New Testament text. It describes the scholarly discipline of biblical text criticism in a way that can help non-scholars understand this field. Ehrman is an excellent communicator, and this makes Misquoting Jesus and engaging read, at least for an introduction to text criticism.

I am not planning to offer an in-depth critique of Ehrman's arguments. So far I've found two fine critical reviews of the book, one by P. J. Williams and the other by Daniel Wallace. Both reviewers are experts in the field of text criticism, the core subject of Ehrman's book. (To this I'd now add a lengthy review by Jim Snapp.)

|

|

|

Ehrman explains in his book how he lost his belief that the Bible was divinely-inspired. At the center of this abandonment of biblical inspiration was his discovery that we do not have access to the original manuscripts of the biblical writings. Moreover, Ehrman learned that the scribes who made copies of the biblical manuscripts sometimes changed the text, either unintentionally, due to error, or intentionally, due to some theological agenda. Thus we cannot be 100% sure that every word in our Bibles, in the original languages, is exactly the same as what was first written. On this basis Ehrman decided to abandon his belief that God inspired the Bible. Here's his argument in his own words:

For the only reason (I came to think) for God to inspire the bible would be so that his people would have his actual words; but if he really wanted people to have his actual words, surely he would have miraculously preserved those words, just as he had miraculously inspired them in the first place. Given the circumstance that he didn't preserve the words, the conclusion seemed inescapable to me that he hadn't gone to the trouble of inspiring them. (p. 211)

Ironically enough, Ehrman seems to agree with the Islamic notion of inspiration, namely, that a holy book can be believed to be inspired only if the actual words are the words of God and if the process of transmission can guarantee that these words have been passed along perfectly. I'm not suggesting that Ehrman would be happy as Muslim, mind you, but only that his doctrine of inspiration seems to be more Muslim than Christian in many ways.

At this point I want to offer four basic observations concerning Ehrman's argument against the inspiration of the Bible (and Christian faith in general).

First, there's nothing in Misquoting Jesus that isn't common knowledge among New Testament scholars, including those of us who have a strong commitment to biblical inspiration and authority. This doesn't invalidate Ehrman's arguments against Christian faith, of course, but it does suggest that one can take his data and end up at very different conclusions, including a strong confidence in the inspiration of Scripture.

Second, Ehrman believes that many of his text critical conclusions are injurious to orthodox Christianity. This is plainly false, since these conclusions are in fact held by many evangelical scholars. In my opinion, there's nothing that Misquoting Jesus points out about the New Testament manuscripts that is threatening to Christian orthodoxy.

Third, Ehrman's book is one more in the "debunk orthodox Christian faith" genre. If you're a New Testament scholar, especially an articulate one, as is Ehrman, and if you can get somebody to publish a book called Misquoting Jesus, you're going to sell a lot of books, and get on secular radio programs, so you'll sell a lot more books, and get more secular press, etc. etc. It does seem more than ironic to me that NPR did an interview with Ehrman, with content that undermines orthodox Christianity, only eleven days before Christmas. I doubt it's because they expected Christians to be giving this book as Christmas presents. Moreover, I expect that when the orthodox corrective to Ehrman's book is published, NPR won't touch it with a ten foot pole. (I'd love to be proved wrong on this point, however.) So, though Ehrman is a much more responsible and balanced scholar than many in the Jesus Seminar, his popular writing and the popular attention it is getting reminds me of what happened with the Seminar's attempt to undermine orthodox faith.

Fourth, I do believe, however, that Ehrman's book does challenge orthodox Christians to clarify or even to correct things we believe about the Bible. In particular, we should be able to answer Ehrman's question: If God inspired the Bible, even making sure that what was first written was inerrant, why did He allow the process of textual transmission to be something less than inerrant?

I'll offer an answer to this question as I continue in this series.

The Text-Critical Case Against Biblical Inspiration, Section A

Part 5 in the series: The Bible, the Qur'an, Bart Ehrman, and the Words of God

Posted for Tuesday, January 17, 2006

In my last post in this series I began to consider a recent challenge to the inspiration of the Bible. It's recent, I should say, in that it appears in a recently published book, Misquoting Jesus, by Bart Ehrman. The arguments Ehrman puts forth are not new, and the evidence for his position is well-known among scholars, including many who uphold the inspiration of Scripture.

What Ehrman proposes one might call "The Text-Critical Case Against Bible Inspiration." It could be boiled down to something like this:

If the Bible is truly inspired by God, then we would expect that what was written in the original manuscripts should have been perfectly preserved, either through the preservation of those manuscripts, or through complete scribal accuracy. After all, why would God inspire the writers of the Bible but not perfectly preserve what they said? Yet when we study the history of the biblical text, we find out that scribes who copied the manuscripts made changes in the text they were copying. Some of these changes were accidental, reflecting human error, others were intentional, reflecting the particular theology of the scribe. Therefore, not only can we have no certainty about what was actually written in the original manuscripts of the Bible, but also we have no reason to believe that God inspired the original writers, because if He had, He surely would have done a better job making sure that that process of preserving His inspiration was a perfect one.

I want to make five comments in response to this argument.

1. You Can't Have Absolute Certainty in Matters of History and Faith

The Text-Critical Case Against Biblical Inspiration seems to imply that if we have anything less than full certainty about the text of the Bible, then we can't have confidence in it or its inspired origin. But this is to ask of history more than it can ever supply. What we should expect from text criticism is not 100% certainty about the biblical text, which is impossible, but rather a high level of confidence that the text reconstructed by text critics is very close to the original. This sort of confidence, I believe, is quite defensible on scholarly grounds.

2. The Text-Critical Case Against Biblical Inspiration Overstates the Problem

This argument greatly overstates the extent to which scribal changes inhibit our ability to "get at" the earliest text of the biblical books. In fact, we can have more confidence about the text of the New Testament, for example, than about any other piece of ancient writing, because we have so many copies of the New Testament from both ancient times and covering a broad array of geography. Yes, there are quite a few passages about which we cannot be sure of the original words, but these are a very small percentage of the New Testament.

3. The Tools Used in Text Critical Case Against Biblical Inspiration Actually Support the Opposite Conclusion

The argument Ehrman makes against biblical authority, ironically enough, supports the opposite conclusion. Ehrman indicates that various scribes changed the biblical text as they made copies. Fine. Let's grant that this is true, as I think it is in some cases. The text critical tools used in Ehrman's argument, however, actually show that we can identify these scribal changes and, to a high degree of probability, show what the text was like before the changes were made. In other words, Ehrman's use of text criticism to point out that scribes "misquoted Jesus" employs scholarly tools that allow us to get back to the more authentic words of Jesus. So, the very critical tools that Ehrman uses to write his book, one might argue, are the tools God has given so we can have confidence that we have access to the actual words He once inspired, or something very close to these words. |

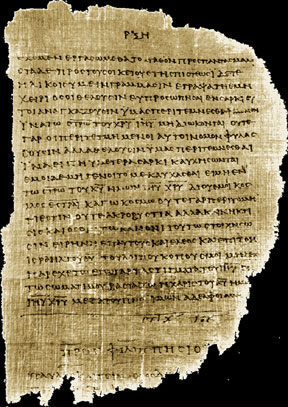

|

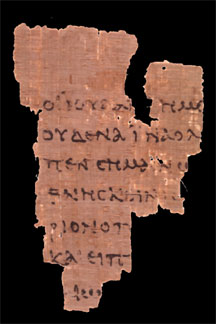

| |

This is p52, the oldest fragment of the New Testament. (The 'p' stands for papyrus, the substance of the fragment.) It has been dated to around 125 A.D. The text is from the Gospel of John, which was written around 90 A.D. So the gap between the original and this copy is about 30-50 years. The text reads (in translation, with bold letters represented in p52): The Jews replied, “We are not permitted to put anyone to death.” (This was to fulfill what Jesus had said when he indicated the kind of death he was to die.) Then Pilate entered the headquarters again, summoned Jesus, and asked him, “Are you the King of the Jews?” (John 18:31-33). |

4. The Disputed Texts Are Not Terribly Significant for Christian Theology and Practice

In my last post I wrote, "Ehrman appears to believe that many of his text critical conclusions are injurious to orthodox Christianity. This is plainly false, since these conclusions are in fact held by many evangelical scholars. From everything I've learned about Misquoting Jesus, there's nothing that this book points out about the New Testament manuscripts that is truly threatening to Christian doctrine." I would add that even if we took out of the New Testament every passage that Ehrman believes, rightly or wrongly, to be questionable, this wouldn't change basic Christian theology one iota.

For example, Ehrman points to a Trinitarian scribal addition in 1 John 5:7-8. The original text of 1 John read,

There are three that testify: the Spirit and the water and the blood, and these three agree.

At some later point a scribe added:

There are three that testify in the Heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Spirit, and these three are one. And there are three that testify on the earth, the Spirit and the water and the blood.

All modern Bibles and translations, to my knowledge, do not print the added portion (except in footnotes). This supports Ehrman's contention that scribes sometimes changed the text of the Bible in light of their theology. Of course it also supports my contention that text criticism allows us to get back to the original text (or close to it, at any rate). Moreover, the Christian doctrine of the Trinity in no way depends upon this particular passage for its biblical support.

I'd go even a step further than this and propose something I haven't actually checked in detail, but I expect is true. If you were to remove from the Bible every single passage where there is legitimate uncertainly about the original text, the impact on Christian theology and practice would be minimal at most. (The only folk I know who would be in trouble are the snake-handling Christians of Appalachia, who base their practice on Mark 16:18, which almost all scholars believe was not part of Mark's original gospel, and which almost never appears in modern Bibles without a note that explains its questionable origins.)

5. The Text Critical Problems with the New Testament Help Us Understand Inspiration More Truthfully

My fifth comment is perhaps the most theologically interesting and substantial. Because it will be longer than the first four comments, I'm going to save it for my next post in this series. Stay tuned . . . .

The Text-Critical Case Against Biblical Inspiration, Section B

Part 6 in the series: The Bible, the Qur'an, Bart Ehrman, and the Words of God

Posted for Wednesday, January 18, 2006

Yesterday I began responding to what I'm calling The Text-Critical Case Against Biblical Inspiration. This case has been made most recently by Bart Ehrman in his book, Misquoting Jesus. (Note: I have now finished reading Ehrman's book. After doing so, I went back and slightly edited what I had written earlier, but didn't change anything substantial. This testifies to the accuracy of the reviews of P.J. Williams and Daniel Wallace, upon which I had been depending. They did not "misquote" Ehrman in their critiques of his book.)

Here's Ehrman's version of The Text-Critical Case Against Biblical Inspiration, in his own words:

As I realized already in graduate school, even if God had inspired the original words, we don't have the original words. So the doctrine of inspiration was in a sense irrelevant to the Bible as we have it, since the words God reputedly inspired had been changed and, in some cases, lost. . . . For the only reason (I came to think) for God to inspire the Bible would be so that his people would have his actual words; but if he really wanted people to have his actual words, surely he would have miraculously preserved those words, just as he had miraculously inspired them in the first place. Given the circumstance that he didn't preserve the words, the conclusion seemed inescapable to me that he hadn't gone to the trouble of inspiring them. (p. 211)

In my last post I already pointed out several flaws in this argument. They were:

1. You Can't Have Absolute Certainty in Matters of History and Faith

Including matters of textual transmission. Ehrman seems to want the impossible, or, a "miracle" as he says, in the passing on of the text.

2. The Text-Critical Case Against Biblical Inspiration Overstates the Problem

Further note: For Ehrman to say that "we don't have the original words" of the Bible is a gigantic exaggeration. I'd argue that it's likely that we have the original words in something like 99% of the New Testament.

3. The Tools Used in Text-Critical Case Against Biblical Inspiration Actually Support the Opposite Conclusion

Ehrman's adept use of text-critical tools shows that we can, in fact, get back behind scribal changes. So we're not out of luck when it comes to accessing the original text, as Ehrman seems to think. God seems to want us to use our brains when it comes to understanding His revelation.

4. The Disputed Texts are Not Terribly Significant for Christian Theology and Practice

Take out of the Bible every passage Ehrman deems significant, and nothing in orthodox Christianity would be impacted.

Today I'll get to my fifth point:

5. The Text Critical Problems with the New Testament Help Us Understand Inspiration More Truthfully

In fact, they help us understand God more truthfully.

I do believe that many of Ehrman's observations about the text of the New Testament are accurate. I agree that we cannot be completely sure, in some cases, what the original writer actually wrote. Though I think Ehrman tends greatly to exaggerate the problem here, to his advantage. Nevertheless, he believes that because we can't be positive of the original words of the Bible, this shows that God didn't inspire those words, because "the only reason . . . for God to inspire the Bible would be so that his people would have his actual words" (p. 211).

I must confess that this argument reminds me of the sort of thing I argued about with my freshman roommates. It's a simplistic argument, and seems completely ignorant of lots of relevant Christian theology. In many ways Ehrman is a sophisticated scholar. But when it comes to his understanding of God and Scripture, he seems strangely naïve. Also, for one who now admits to being an agnostic, Ehrman seems pretty certain about what God should have done when it comes to inspiration. I'd suggest that he'd have done better to consider what God actually did and then try to figure out what this says about God.

According to Ehrman, the only reason for God to inspire the Bible would be so that people would have his actual words. This is a far too limited view. As I showed earlier in this series, through the example of the sapphire, it would be possible for God to reveal His truth and to keep a biblical from error, without actually inspiring the words of revelation at all.

The question Ehrman should have asked was: What does it tell us about God that He inspired the writers of Scripture but did not perfectly preserve what they wrote down? The answer, I think, is that God was looking for something beyond making sure we always had His actual words. Now, even as one who actually believes that the words of Scripture are inspired by God and also chosen by the human writers, I would nevertheless disagree with Ehrman's basic contention about the purpose of inspiration. God's primary purpose in inspiring the writers of Scripture was not so that people would have His words, but so that they would be drawn into a truthful relationship with Him. The words matter, to be sure, but only as a vehicle for a relationship of faith with the living God. Some modest uncertainty about the words might, it seems, cause one to lean more upon God and less upon the words themselves.

Ehrman's argument about Scripture reminds me of criticisms I have heard about Jesus and his teaching. "If Jesus really was the Messiah," some have argued, "then surely He would have told people outright. He wouldn't have kept it such a secret. He would have been much clearer." Or, others have said, "If Jesus wanted people to know the truth and believe in Him, he wouldn't have taught in parables. Rather, he would have been much clearer about what He meant." These two arguments, like Ehrman's, assume something that just isn't true. They assume that God, and Jesus as His Son, should be in the business of making everything crystal clear to us. But this assumption is wrong. God's revelation is much less obvious than this. Now, as it says in the New Testament, we see only "through a glass darkly," (1 Corinthians 13:12). The clarity that Ehrman and others want won't come, in Christian belief, until later, when we finally see God face to face.

Ehrman's argument about inspiration seems almost silly when you think about it. He seems to think that if God really wanted us to have His words and to believe they were His words, then He would have made sure the copying process was accurate, or that the original manuscripts were preserved, or something like this. But even these states of affairs, if they were true, would hardly give the kind of clarity and certainty Ehrman seems to want. Presented with the original manuscript of Paul's letter to the Romans, for example, Ehrman could simply say, "Well, that's all well and good. But these aren't the words of God. They're the words of a man. That's all." So God's strategy of accurate preservation wouldn't work, after all, to convince anyone who chose to disbelieve in biblical inspiration.

| If I were to believe, as Ehrman believes, that inspiration only works if there's absolute certainty about the divine origin and preservation of the words, then I'd say the whole notion of people writing documents was doomed from the start. Surely God could have done better than this, way better, like rearranging the stars so that they spelled out God's words. Now that would be impressive. Or perhaps God could have engraved His words on the smooth face of Half Dome in Yosemite Valley, far above where humans could have carved them. Now that would be both highly impressive and relatively permanent. My point is that what Ehrman wants from God wouldn't have been fulfilled even if God had done what Ehrman dictates. The whole notion of human writers and scribes and manuscripts is far too messy for the kind of certainty Ehrman thinks is necessary for inspiration to be true. |

|

| |

Now that would pretty much convince most skeptics, though I'm sure some would find a way to explain away God's action.

|

But, one might object, if we can't be positive about the divine origin of every word in the Bible, then how can we trust the Bible at all? I'll try to answer this question in my next post.

How Ehrman Exaggerates When Talking About Problems in the Text of the New Testament

Part 7 in the series: The Bible, the Qur'an, Bart Ehrman, and the Words of God

Posted for Friday, January 20, 2006

Today I continue my critique of Misquoting Jesus by Bart Ehrman. In this book he shows that the textual transmission of the New Testament did not perfectly preserve the words that were originally written by the writers of the New Testament document. On this basis, Ehrman rejects the inspiration of the New Testament itself. In his introduction he writes:

If [God] wanted his people to have his words, surely he would have given them to them. . . . The fact that we don't have the words surely must show, I reasoned, that he did not preserve them for us. And if he didn't perform that miracle, there seemed to be no reason to think that he performed the earlier miracle of inspiring the words. (p. 11)

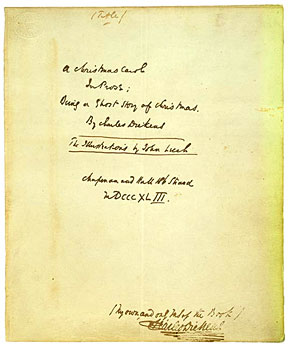

Before I offer a further critique of this argument, I must note Ehrman's tendency to exaggerate the case against the words of the New Testament. In that last quotation he says that "we don't have the words" God may have inspired. But this is to overstate his case in the extreme. It's true that we don't have the actual manuscript of Paul's letter to 1 Thessalonians, for example, so we don't have the actual words Paul wrote down in the first place in this most literal sense. This would be in contrast, for example, to the case of Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol, where we actually have the manuscript Dickens himself wrote. But this is a truly exceptional and odd standard. Though I've never seen a Dickens manuscript, most folks would be happy to grant that I've read the actual words of A Christmas Carol since I've read that story many times. |

|

| |

This manuscript of A Christmas Carol is preserved in the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York City. The cover page shown above can be found online.

|

I would argue that the situation is similar with the New Testament, even though we don't have the original manuscripts any more. Take 1 Thessalonians, for example. There are 1493 Greek words in the standard Greek text of this Pauline letter, by my count. Of these, text critical scholars are uncertain of about 20 words (including 3 instances of "the," 3 instances of "in," and 5 instances of "and"). Only 4 of the 20 disputed words make any difference at all in the meaning of the letter, and this difference isn't about fundamental theological truth (nepioi/epioi in 2:7; kalountos/kalesantos in 2:12; kai diakonon in 3:2). At any rate, this means that we do not have relative certainty about 1.3% of the words in 1 Thessalonians. In fact, it's highly likely that we have the original words, but text critical scholars aren't sure which words among those we have were original. To say that "we don't have the words" of 1 Thessalonians is to use language strangely, and to establish a standard for textual transmission that requires, as Ehrman seems to want, a miracle. Given Ehrman's requirement for biblical inspiration, I don't even know why he bothers with the details. It would be simpler for him to say that the whole notion of people writing texts and having them passed on is simply inconsistent with divine revelation. This is, I believe, what Ehrman thinks.

In one place Ehrman writes: "there are more differences among our manuscripts than there are words in the New Testament" (p. 10). Now this sounds bad for the one who upholds biblical inspiration. But, in fact, Ehrman's statement is misleading. Let me explain.

At current count, according to Ehrman, there are over 5,700 Greek manuscripts of the New Testament (p. 88). Some of these manuscripts cover the whole New Testament. Most contain portions only: a book, a collection of books, or even a short excerpt. In the accepted critical text of the Greek New Testament, there are just over 180,000 words. So, when Ehrman says "there are more differences among our manuscripts than there are words in the New Testament," let's assume for the sake of argument that there are 200,000 such differences among the 5,700 manuscripts. Now, let's suppose that the average New Testament manuscript has 4,000 words. I don't know if this is true, but it's a fairly conservative number. The Gospel of Mark alone has over 11,000 words. This would mean that the total number of words in the New Testament manuscripts is 5,700 times 4,000, which equals 22,800,000. So, if there are 200,000 differences among the manuscripts, then less than 1% of the words of the manuscripts are text-critically questionable. Ironically – I did not plan it this way – this is similar to the percentage we found in the case of 1 Thessalonians (which I chose, by the way, because I did my Ph.D. dissertation on this book, and know if fairly well).

If I've lost you with this argument, or if my reasoning is somehow messed up, or if you're not a New Testament specialist and you don't know how to evaluate what I'm saying, let me offer some supporting evidence. Almost every English Bible translation will tell you when there is some ambiguity in the textual basis for their translation. This usually goes in footnotes that read: "Some early manuscripts have . . ." or "Some witnesses read . . ." or something like this. If you flip through the New Testament, you'll see these footnotes on quite a few pages. But if you figure out the percentage of disputed words, it will be less than 1%. (The only places where a large chunk of text is disputed are John 7:53-8:11 [the woman caught in adultery] and Mark 16:9-19 [the longer ending to Mark].) What this means is that text critical scholars, spanning a wide range of theological commitments, are largely in agreement about the originality of the vast majority of the New Testament.

If my numbers are anywhere near accurate, or if the footnotes in Bible translations are to be believed, this means there are two ways of conveying the same basic fact:

"There are more differences among our manuscripts than there are words in the New Testament."

– Bart Ehrman |

"We can have a high level of confidence that the vast majority of the words in the Greek New Testament appeared in the original manuscripts."

– Mark Roberts |

Both of these statements are true. And both are based on the same evidence. And both reflect the bias of the writer. But the simple fact is that most of the time most of the New Testament manuscripts are in agreement with each other. And when there is a disagreement, most of the time text critics are able to discern, with a high degree of probability, which reading is original. This leaves a very small percentage, maybe 1% of the New Testament, where we have genuine textual ambiguity. All of these passages, by the way, could be removed from the Bible without any major impact on Christian theology. I know this for a fact because I've been a teacher and preacher of orthodox (well, I hope) Christian theology for more than 20 years, and I've always made a special effort not to base anything I'm preaching or teaching on a text for which there isn't sufficient manuscript support.

Ehrman is clever in his use of language to favor his argument, yet I fear his cleverness may mislead many readers. In his conclusion, for example, Ehrman states, "even if God had inspired the original words, we don't have the original words" (p. 211). Yes, we don't have the manuscript of 1 Thessalonians, for example, and in this sense we can't look at the original words Paul wrote on the page. But virtually every responsible New Testament scholar believes that the critically-reconstructed Greek text of 1 Thessalonians is very close to what Paul once wrote. This can't be proved beyond a shadow of a doubt, of course. But there's no reason to believe that what we read today, if we can read Greek, is substantially different from what Paul wrote. Where we're not sure about which words Paul wrote, we actually have the words, we just aren't positive which ones were original. Moreover, at any rate, the disputed words contribute very little to our understanding of 1 Thessalonians.

I don't think Ehrman is being intentionally deceptive when he writes things like "There are more differences among our manuscripts than there are words in the New Testament" and "we don't have the original words." Rather, I think he is himself confused. He became confused, according to his own witness, as a young college student, and especially while in seminary. And that confusion has stayed with him for thirty years. Though Ehrman's an expert in the craft of text criticism, and thought he's an exemplary communicator, the philosophical and theological implications he draws from text criticism are poorly reasoned and quite unconvincing.

Yet, one might object, if we can't be sure of 1% of the New Testament words, or even .1%, then how can we trust the New Testament? Doesn't the process of textual transmission undermine any confidence in the biblical text, even if we grant that the originals were divinely inspired?

I'll answer this question in my next post in this series.

Should the History of the New Testament Text Undermine Our Confidence in the Bible?

Part 8 in the series: The Bible, the Qur'an, Bart Ehrman, and the Words of God

Posted for Monday, January 23, 2006

Should the history of the New Testament text undermine our confidence in the Bible? For professor and author Bart Ehrman, the answer to this question is "Yes." In fact, his realization that the original text of the New Testament was passed on imperfectly led Ehrman to abandon his belief that the Bible was inspired, and ultimately his belief in God. Though he acknowledges his agnosticism elsewhere, in the conclusion to Misquoting Jesus, Ehrman writes,

As I realized already in graduate school, even if God had inspired the original words [of Scripture], we don't have the original words. So the doctrine of inspiration was in a sense irrelevant to the Bible as we have it, since the words of God reputedly inspired had been changed and, in some cases, lost. Moreover, I came to think that my earlier views of inspiration were not only irrelevant, they were probably wrong. For the only reason (I came to think) for God to inspire the Bible would be so that his people have his actual words; but surely if he really wanted people to have his actual words, surely he would have miraculously preserved those words, just as he had miraculously inspired them in the first place. Given the circumstance that he didn't preserve the words, the conclusion seemed inescapable to me that he hadn't gone to the trouble of inspiring them. (p. 211)

In my last post I showed how Ehrman tends to exaggerate the problem of the biblical text. To say "we don't have the original words" is odd, if not careless, given the fact that we can be confident of something like 99% of the words in Greek text of the New Testament.

Yet Ehrman seems to believe that if God had actually inspired the biblical writers, then He would also have perfectly preserved the original words of these writers. Ironically, in this argument Ehrman is in agreement with some of the most conservative of all Christian fundamentalists. For example, in The Answer Book by Samuel Gipp, published by Chick Publications, we find a strident criticism of most fundamentalists, who, according to Gipp, believe that the original writings of the Bible were inerrant, but not the copies made from these originals. Here are some of Gipps's points:

It is somewhat confusing and unexplainable that a person could claim that God could not use, sinful men to preserve His words when all fundamentalists believe that he used sinful men to write His inspired words. Certainly a God who had enough power to inspire His words would also have enough power to preserve them. I highly doubt that He has lost such ability over the years.

Why would God inspire the originals and then lose them? Why give a perfect Bible to men like Peter, John, James, Andrew and company and not us?

Thus, to believe in a perfect set of originals, but not to believe in a perfect English Bible, is to believe nothing at all.

Of both Erhman, an agnostic who rejects biblical authority, and Gipps, a fundamentalist who upholds the divine inspiration of the Kings James Version, could be correct in their criticism of those who affirm the inspiration of the biblical autographs but not the perfection of the transmission of the text. It seems ironic to me that Bart Ehrman, a highly-regarded critical scholar, makes an argument that is at home among arch-conservative Christians. And it suggests, a black-and-whiteness in Ehrman's argument that should give us pause.

But, one might object, if it's true that we can't be sure of a percentage of the words in our Greek New Testament, doesn't this undermine our confidence in biblical authority? Even if that percentage is 1%, or even .1%, how can we trust the Bible to teach us God's truth?

I want to respond to this question by using a couple of map analogies. These will, I think, help us understand how we can trust the Bible and its divine inspiration even if the textual transmission process wasn't perfect. (I had thought of these analogies two weeks ago, and then found that Jim Snapp employed another map analogy in his lengthy critique of Ehrman.)

1. The Case of the "Topos"

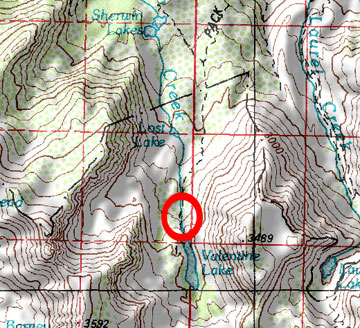

"Topos," as they're affectionately called by hikers, are produced by the U.S. Geological Survey. They're those green-tinted maps with zillions of squiggly lines that show in detail the terrain of the wilderness. Serious hikers wouldn't go off into the forest without carrying a topo. They've guided millions of us to our intended destinations safely, and prevented us from getting lost in the wilderness, something than can prove to be fatal.

But folks who use topos regularly know that they are not 100% accurate. Geological features are almost always represented correctly, since they tend to remain in place over the years. But man-made elements aren't quite so permament. Shacks, trails, and even roads can move over time. And, since some of the topos were drawn many years ago, it's not uncommon for the representations of these non-natural items to be incorrect on otherwise trustworthy topos.

Does this mean I don't take a topo when I hike off into the High Sierras? Hardly. Does this mean I don't rely upon what I read on the map? No. I literally put my life in the hands of my topo, especially when I'm going off the trail into a region I've not explored before. But it does mean that I'm always a little cautious about trusting that every item on the topo is 100% correct. Not only can cartographers make mistakes, but also the things they represent can change. (I supply an example of such a change in the picture to the right.)

Now if one were to argue that since topos have errors, a hiker would be well-advised not to use them, this would be a silly argument, one that no serious hiker would accept. Yet this is rather like Ehrman's argument concerning the Bible. Since he can't be 100% sure of every feature in the biblical "map," he's decided to live his life "mapless." He certainly seems to have more confidence in his ability to find the right path on his own than I do in mine. That's for sure. |

|

| |

This is a part of a "topo" of the High Sierra of California, near Mammoth Lakes. According to this map, the trail from Sherwin Lakes to Valentine Lake begins on the east side of Sherwin Creek, but then moves to the west side of the creek near the outlet of Valentine Lake. When I hiked this trail five years ago, however, it stayed on the east side of the creek all the way to Valentine Lake. My supposition is that at some point the trail was rerouted, but the USGS topo was not updated. |

Of course Ehrman argues that the fact that we can't be sure of certain features in the biblical "map" casts doubt upon its divine inspiration. Why put such trust in Scripture? he would ask. My confidence in the Bible, is similar similar to my confidence in topos. I've used them both for so long, and been guided so well through their use, and known so many others who have found them to be trustworthy, and have discovered that they accurately portray the realities and challenges of life, that I'm willing to trust both my topos and my Bible to guide me.

Tomorrow I'll put up my other map analogy. Stay tuned . . . .

Should the History of the New Testament Text Undermine Our Confidence in the Bible? (continued)

Part 9 in the series: The Bible, the Qur'an, Bart Ehrman, and the Words of God

Posted for Tuesday, January 24, 2006

In yesterday's post I began explaining why I think we can trust the Bible, even though we can't be 100% sure that every word in our existing Greek text of the New Testament was precisely the same in the original documents. I used the analogy of topos, U.S. Geological Survey topographical maps. Even though these are not perfect in every detail, they are extraordinarily helpful and trustworthy. Only a fool would hike out into an unfamiliar wilderness area without a topo, even if it's possible that a few details in the map might be incorrect. Today I'll suggest another map analogy that helps to explain why we should put our trust in the Bible even if our manuscript evidence isn't perfect.

2. The Case of Map "Traps"

Map "traps" seem like an urban legend: a popularly-told and widely-believed story that turns out not to be true. But from everything I've read, map traps really exist. (For example, check out this sane piece from The Map Room.)

What is a map trap? It's an error in a map that was intended by the map maker. The purpose of a map trap is to give a map a unique identity marker, so that if someone makes an illegal copy of a map, the owner of the copyright can identify the map through its traps.

I remember years ago reading an article about Thomas Brothers maps, in which a representative of the company admitted the existence of map traps. (This article may be the one mentioned in this post from The Straight Dope, but I can't be sure.) Thomas Brothers publishes the definitive road maps of Southern California, ones I have used for over thirty years. I'm pretty sure I once found a trap, though I've forgotten the precise details. I was riding my mountain bike in a desolate area, looking for an access road to a trail. The road was plainly drawn on the map, but when I got to the right location, there was no road. Nor was their evidence that a road had ever been there. It was either an unintended mistake or a map trap.

I found a specific example of a map trap on OpenStreetMap.org, a website for map lovers. A published map of Bristol, England, includes a street ironically entitled "Lye Close." It's placed adjacent to Canynge Square. But if you visit the square, you'll find only a row of attractive houses. Lye Close is, indeed, a lie. More precisely, it's a trap to prevent copyright infringement.

So, if map traps are a reality, though my analogy works even if they aren't, is this a reason to live without maps? The answer seems obvious, doesn't it? I have been using Thomas Brothers maps for over thirty years. In every case, save one, they have guided me correctly. (Sometimes, if my map is outdated, it will not have new roads.) The thought of trying to get around Southern California without Thomas Brothers maps boggles the mind. I'd probably still be lost out there somewhere in the maze of Southern California streets. (Maps by other publishers probably also have traps, by the way.)

Though I don't know Bart Ehrman personally, my guess is that he uses maps that contain errors. If he were to find out that his maps have errors, perhaps even map traps added intentionally by the publishers, would Ehrman stop using his maps? I rather doubt it. |

|

|

Above: A portion of a map of Bristol, England,

featuring Lye Close.

Below: Houses along Canynge Square where Lye Close would be,

if the street existed.

|

|

Now I expect he'd respond to this by saying, "Your analogy doesn't work, because the map publishers have never claimed that their maps are inerrant. Nor have they claimed that God has miraculously inspired their maps. I can accept the fact that human cartographers make mistakes, or even include map traps. But I cannot accept the idea that God inspired the biblical writings, since He didn't take care to preserve them perfectly. We don't have the 'original words' of the biblical documents in some cases."

I would respond to this, first, by saying that we don't need perfect preservation to have trustworthy access to the original words of Scripture. As I've said before in this series, if you take out of the Bible every passage for which there is a major textual question, no matter of Christian theology is affected. What God has accurately preserved for us is much more than enough to know Him and His truth.

Second, I'd observe that Ehrman's rejection of the Bible seems to be a reaction to the extreme conservatism of his teenage faith. It's no coincidence, as I showed in my last post, that Ehrman's view of what God must do is virtually the same as the position of extremely conservative fundamentalists. Unfortunately, and for reasons I don't know, rather than have his Christian theology of Scripture become more mature as he studied, Ehrman seems instead to have frozen his understanding of biblical inspiration in some juvenile, hyper-fundamentalist mode.

Third, I doubt that it would make much difference to Ehrman if we discovered all of the original New Testament manuscripts intact (in a secret vault in the Louvre in Paris, for example). I'd say, "Look, here are the manuscripts, perfectly intact. God has miraculously preserved them." He'd say, "Well, that's great. But this still doesn't prove that what's in them is divinely inspired. The Bible is a human book, whether or not you have the original manuscripts."

Fourth, I'd admit that it would be easier if God had inspired and preserved the Bible in a more straightforward and easily defensible way. But God's ways are rarely easy, and what makes sense to us is often not the way God does things. When God said, "My ways are not your ways" (Isaiah 55:8), though He wasn't speaking directly to the issue of biblical inspiration and textual preservation, He was telling the truth. Before we get too puffed up by our ideas of what God must and must not do, we had all better go back and read the latter chapters of Job.

Fifth, the fact that we don't have 100% certainty about all of the words in the New Testament isn't the result of some divine oversight. Nor should it encourage us to reject biblical inspiration. In fact, this reality should help us realize something profoundly true about God, something that is in fact revealed in the Bible in countless ways, as well as the way in which the biblical text has been transmitted to us. I'll address this theological truth in my next post.

The God of Imperfect Textual Transmission

Part 10 in the series: The Bible, the Qur'an, Bart Ehrman, and the Words of God

Posted for Thursday, January 26, 2006

I believe Bart Ehrman is correct when he observes that the text of the New Testament was not passed on perfectly from the original autographs to the manuscripts upon which our Greek New Testament is based. I've explained in some detail, however, that I think Ehrman exaggerates the problem, and that his rejection of biblical inspiration on the basis of textual uncertainties is unnecessary and unwise.

Nevertheless, I do think the imperfect textual transmission process is something worth considering as we talk about the inspiration and authority of Scripture. Ultimately, I believe, this issue forces us to confront what one might call "the God of Imperfect Textual Transmission."

For the sake of argument, I'm going to assume that God did in fact inspire the writers of the Bible in some strong sense. I believe this to be true, but I don't want to get waylaid at this point defending this conviction. So let it be an assumption. Therefore, I believe that God both inspired the original manuscripts of the Bible and did not perfectly preserve these manuscripts, even though what we have today is very close to what was originally written.

Why would God do this? Why would God do what makes no sense to Bart Ehrman, to very conservative fundamentalist Christians, and, for that matter, to Muslims, who believe that the words of Allah have been perfectly preserved in modern copies of the Qur'an? Why would God inspire the writers of the documents that would end up in the Bible, yet not guarantee their perfect transmission?

My answer: Because that's the kind of God we have. If you think of it, what God has done with Scripture is exactly the same as what God has done with creation. Christians believe that God created all things good, very good, in fact. Creation was perfect. And then what did God do? He entrusted His perfect creation into the hands of human beings, who sinned and promptly messed us God's perfect world. Yet not completely, of course. The original goodness is still there.

Or consider another example. Through the cross and resurrection, Jesus defeated sin and death, and inaugurated the new creation. God intends for the world to hear this wonderful news so that all nations might be numbered among His disciples. And how is God accomplishing this goal? Through human beings. Through the very human institution of the church. Even with the help of the Holy Spirit, the church is not perfectly passing on the good news of Christ, or perfectly living it out, for that matter.

So in the matter of creation, and in the matter of redemption, God began with a perfect work, and then entrusted that work to human beings, who have continued it imperfectly. Doesn't it make sense, therefore, that the God who inspired the Scripture, even assuring that it was in some sense a perfect written revelation, would entrust this revelation to human scribes, who would pass it on imperfectly?

Ehrman's argument, therefore, isn't merely with the God of biblical inspiration but imperfect textual transmission. His argument is with the God who actually entrusts His treasures to human beings. His argument is with the God who actually empowers human beings to mess up what He has perfectly created or revealed. Even if Ehrman believed that the Bible was the Word of God, he'd be very unhappy with the God revealed in that Word. Ehrman seems to want a God who doesn't enter into partnership with limited, fallible, and even sinful humanity. But, unfortunately for Ehrman and others like him, that's the God we have.

| Ehrman is certainly not the first person to be uncomfortable with the extent to which God has made us His partners. Ironically, this discomfort can be found in some of the scribal changes in the biblical text, though not in a passage Ehrman discusses in Misquoting Jesus. In Paul's first letter to the Thessalonians, he refers to Timothy as "our brother and co-worker of God [synergon tou theou] in the gospel of Christ" (1 Thess 3:2). Or at least this is what text critics believe is the original description of Timothy. In fact those words appear in relatively few old manuscripts. If you were to examine many of the oldest manuscripts of 1 Thessalonians, you mostly find either: "our brother and servant of God in the gospel of Christ," with "servant" replacing "co-worker," or "our brother and servant of God and our co-worker in the gospel of Christ." In either case, the scandalous implications of "co-worker of God" have been "corrected." Text critics have shown, quite convincingly, I believe, that the original phrase was "co-worker of God." Those who copied 1 Thessalonians, uncomfortable with this phrase and, as is probable, believing it to be an error, "corrected" it so that Timothy is no longer God's co-worker, but rather God's servant. Of course there's no doubt that Paul believed Timothy to be God's servant. But in 1 Thessalonians 3:2, he used the much more unsettling description, "God's co-worker." |

|

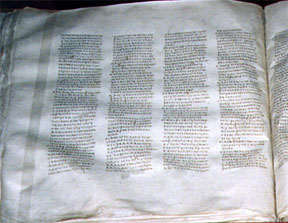

| |

This is a portion of Codex Sinaiticus, one of the oldest biblical manuscripts. It is usually dated to the mid-fourth century A.D. This manuscript reads "brother and servant of God."

|

I must say I can understand scribal reluctance in this case. And I can understand why Bart Ehrman would expect God to have done less trusting of human beings and more guaranteeing of the textual transmission of the biblical manuscripts. Whenever God trusts us to be His partners and to do His business, inevitably we mess things up, at least a bit.

Tomorrow I'll complete this discussion of the God of Imperfect Textual Transmission.

The God of Imperfect Textual Transmission (continued)

Part 11 in the series: The Bible, the Qur'an, Bart Ehrman, and the Words of God

Posted for Friday, January 27, 2006