Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Volume 3 of 3 (printer-friendly format)

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com. Thank you.

Jesus Revealed: Know Him Better to Love Him Better, by Mark D. Roberts

Please pardon some shameless self-promotion, but I really do think this book has something to offer. Jesus Revealed examines many names and titles of Jesus (Son of God, Son of Man, etc.), explaining their historical, theological, and personal significance. Plus, I've added an appendix that answers the question "Was Jesus Married?" This book includes study questions for personal or group study. I've heard that it's helpful been helpful in adult classes and small groups. For more information or to purchase, click here.

Do Historical Sources from the Era of the Gospels Support their Reliability? Section A ![]()

Part 21 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Monday, October 24, 2005

Do historical sources from the era of the gospels support their reliability? This question can be broken down into a couple of sub-questions:

When the gospels refer to people or places that can be identified from other sources, do these sources confirm what we read in the gospels?

Do non-Christian writers from the time in which the gospels were written support the gospels' portrayal of Jesus?

Before I respond to these questions, I must first say that there is not a lot of evidence to go on here. For one thing, the biblical gospels refer to only a few people who are mentioned in extra-biblical sources, though we have more to go on when it comes to geography. Moreover, secular historians writing within a century of Jesus's death show only the tiniest interest in Jesus. This shouldn't be surprising, of course, because from the perspective of Roman historian writing at this time, Jesus was an insignificant blip on the screen, nothing more. He only became interesting to secular historians and critics as the Christian movement grew in size and influence. Nevertheless, where the biblical gospels do overlap with secular history, the net result is a positive one for the gospels.

When the gospels refer to people or places that can be identified from other sources, do these sources confirm what we read in the gospels?

Yes, this is certainly true when it comes to the prominent historical landmarks of Jesus's day. When the gospels identify major leaders, for example, they get the facts right. Jesus was born while Augustus was indeed the Roman emperor (Luke 2:10), and Jesus began His ministry during the reign of Tiberius (Luke 3:1). Furthermore, the gospels rightly identify the various Herods who impacted Jesus's life and ministry (for example, Matthew 2:1-22; 14:1-5).

The geography of the gospels is clearly that of first-century Palestine, not some first-century Narnia. Once again, the evangelists put the major landmarks in the right places. When they place Capernaum by the Sea of Galilee, for example, this is correct. Certain geographical references in the gospels, however, can seem perplexing, though these can usually be accounted for by a combination of careful exegesis, up-to-date archeology, and an open mind.

| For example, Matthew, Mark, and Luke all tell the story of Jesus casting out demons from a man and into a herd of pigs which then rush into the Sea of Galilee and drown (Matthew 8:28-34; Mark 5:1-20; Luke 8:26-39). Mark and Luke place this event in the country of the Gerasenes, while Matthew describes it as taking place in the land of the Gadarenes. Not only does this seem to be a contradiction among the gospels, but the ancient towns we know as Gadara and Gerasa were not close enough to the Sea of Galilee for the event to have taken place nearby. Gadara was about 5 miles from the Sea of Galilee, whereas Gerasa was about 30 miles away. Among the various options available for interpreters are the following: |  |

|

1. The evangelists were speaking of the region near Gadara and/or Gerasa, not the towns themselves. We all do this at times. If I meet someone from another state, I'll often say that I live in Orange County, California. Or if, for example, I meet someone from another country, I might say that I live in Los Angeles, even though I really live 50 miles away. In truth, I often say that I live near Disneyland, which almost everybody has heard of. In fact I live 12 miles away, though Disneyland is in Anaheim, which is three cities removed from Irvine. So when people ask where I live, I choose from a variety of answers: Irvine, Orange County, Los Angeles, near Disneyland. All of these are true in a sense.

2. The event happened in another town known as Khersa, which was on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, and which in Greek would have been spelled in the same was as Gerasa.

3. Geographical imprecision wasn't unusual in history writing of the first-century A.D., and shouldn't be counted against the overall reliability of the evangelists.

When it comes to historical personages, the gospels get the main characters right. But, as in the case of Gadara/Gerasa, you'll find similar confusion regarding Quirinius, who was ruling during the time of the census that brought Mary and Joseph to Bethlehem (Luke 2:1-2). Luke refers to a census "taken while Quirinius was governor of Syria" (v. 2). Given the fact that King Herod the Great was reigning when Jesus was born, this census must have taken place around 6 B.C., since Herod died in 4 B.C. (Yes, our calendar is wrong by about 6 years.) But secular sources date Quirinius' term of office to 6-9 A.D., or about 10-15 years after the birth of Jesus. Some scholars have seen this as evidence of Luke's inaccuracy as a historian. Yet close attention to the grammar of Luke's claim in verse 2 and to the long career of Quirinius allows for several ways to view Luke as historically accurate. (I don't have time to get into the various theories right now.)

I don't mean to suggest that it wouldn't be nicer if Luke had named as governor of Syria the Roman who actually held that office in 6 B.C. It would be. But if you have done much study of ancient history, you know that apparent confusions like this are frustratingly common. So the tendency of some scholars to rush to judgment against Luke is unwarranted, both in this case and in others like it. When I was in graduate school, some (but not all) of my professors would summarily reject an evangelist's accuracy by saying things like, "Luke is wrong here about Quirinius' governorship" or "Mark has obviously confused the location of Gerasa." Arguments in defense of the gospel writers' accuracy were either not considered or were glibly rejected as a remnant of naïve fundamentalism. This seemed ironic to me, since these same professors often spent hours in class teasing nuanced meanings out of ancient texts. They were experts at this sort of painstaking exegesis, truly. Yet when it came to the possible historicity of the gospels, nuance and thoughtful exegesis was often rejected in favor of what could only be called fundamentalist-like literalism: "Luke says it. It's wrong. And that settles it."

I believe that if we work hard on understanding what the gospel writers really meant, and if we allow for the inherent imprecision of ancient records, and if we judge the gospels by the standards of their own time, then the overlap of the gospels with secular history works to their favor. When the biblical gospels speak of people or places, they get all the major items correct, as well as most of the minor ones. There are some places in which the gospels seem at first to be less than accurate, but none of these is terribly significant for the author's main purpose, and all of these cases can be interpreted in ways that uphold the historical precision of the evangelists.

Tomorrow I'll address the question of whether secular references to Jesus confirm or undermine what we find in the gospels.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Do Historical Sources from the Era of the Gospels Support their Reliability? Section B ![]()

Part 22 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Tuesday, October 25, 2005

Yesterday I began considering the relationship of the New Testament gospels to secular historical sources. I showed that when the gospels refer to people or places that are found in these sources, the gospels get the major facts right. Today I want to respond to a related question:

Do non-Christian writers from the time in which the gospels were written support the gospels' portrayal of Jesus?

As I mentioned yesterday, there is little about Jesus in non-Christian sources within a century of His death. From the perspective of Roman history, Jesus just wasn't all that important until at least a century later, when His followers began stirring things up across the Roman Empire.

Today's post will summarize findings from a 6-part series I did called: How Can We Know Anything About the Real Jesus? If you're looking for a more detailed conversation, please check out that series.

Roman Sources

A Letter from Pliny to Trajan

Around 112 A.D. a Roman governor named Pliny wrote to the Emperor Trajan asking about how to deal with troublesome Christians. In this letter he mentioned that the Christians "sing responsively a hymn to Christ as to a god" (Letters, 10.96).

Suetonius: Life of Claudius Around 110 A.D. the Roman historian Suetonius appeared to mention Jesus in a passage that reads: "Since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, he [Claudius] expelled them from Rome." (Claudius, 25.4). From a Roman perspective, Christians were unruly Jews, being stirred up by one called Chrestus (a version of Christ). Tacitus: Annals In 109 A.D. the Roman historian Tacitus mentioned Christ in a discussion of how the the Emperor Nero had treated Christians after the terrible Roman fire in 64 A.D.

|

|

|

Bust of the Roman Emperor Claudius (from the Vatican Museum) |

||

Jewish Sources

Jesus is mentioned several times in the Jewish Talmud, but these passages were written down several centuries after Jesus's death. The one early, non-Christian Jewish source of information about Jesus is the historian Josephus.

In one place in his Jewish Antiquities Josephus mentioned Jesus indirectly. His focus was on the killing of James, who was identified as "the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ" (Ant. 20.9.1). In this context Josephus had no need to say more about Jesus himself.

The other passage where Josephus mentioned Jesus is disputed because it comes to us only by way of medieval Christian sources, and these sources appear to have doctored the original text. Josephus was in the process of describing Jewish conditions under Pontius Pilate when he wrote something like:

Now there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man; for he was a doer of wonderful works, a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him both many of the Jews and many of the Gentiles. He was [the] Christ. And when Pilate, at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to the cross, those that loved him at the first did not forsake him; for he appeared to them alive again the third day; as the divine prophets had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him. And the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct at this day. (Ant. 18.3.3, italics added)

Scholars debate which portions of this description are original to Josephus, and which were added later. The portions I have italicized reflect Josephus's concerns and language, and may well have come from his pen.

Addendum: Other Jewish Sources

You may have noticed in that, in describing Josephus's writings, I used the awkward phrase: "the one early, non-Christian Jewish source of information about Jesus is the historian Josephus." This wasn't just convoluted style, but an important reminder that we actually have several early, Jewish testimonies about Jesus outside of the gospels. These come from the writers of other New Testament documents, most of whom were Jews who believed that Jesus was the Messiah. We'd call them Christians, but they would have thought of themselves as Jews.

The writers of the New Testament, with the exception of Luke, were not attempting to write anything like history. But occasionally in their writings they refer to Jesus in ways that help to fill in the historical blanks. Perhaps the best illustration comes from 1 Corinthians 15, a passage I referred to earlier in this series. It reads:

For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. (1 Corinthians 15:3-5)

Paul wrote this in the early 50's A.D., referring to oral traditions he had received earlier. So we have in this passage historical information that comes from within 10-15 years of Jesus's death. You'll notice that there isn't anything here about Jesus's life. The tradition focuses on that which was believed by the early Christians to be most important for salvation: His death, burial, and resurrection.

Clearly this information is not coming from neutral observers. It was formulated by early Christians who believed that Jesus was the Christ (Messiah), and who believed that He was the Savior. So this passage doesn't help answer the question of non-Christian sources for Jesus. But it does reveal some of the earliest purportedly historical information about Jesus, information that is external to the New Testament gospels.

Notice, as I have mentioned previously with respect to the gospel writers, that the historical traditions about Jesus were shaped according to the early Christian theological perspective. Jesus died "for our sins in accordance with the scriptures." Similarly, he was raised "in according with the scriptures." These are theological statements, to be sure. But, contrary to the assumptions of some scholars, the fact that they are theological does not rule out the possibility that they are also statements based upon what really happened. In fact, this passage from Paul illustrates why history mattered so much to the early Christians. They believed that what actually happened to Jesus, His death and resurrection, was the locus of God's salvation. If Jesus had not actually been crucified and raised, then, as Paul said a few verses later in 1 Corinthians, "then our proclamation has been in vain and your faith has been in vain" (1 Corinthians 15:14).

In this post and the last one I've considered the relationship of the gospels to more or less contemporaneous historical sources. In my next post I'll look at how archeology impacts our estimation of the reliability of the gospels.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Does Archeology Support the Reliability of the Gospels? Section A ![]()

Part 23 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Thursday, October 27, 2005

Does archeology support the reliability of the gospels? The basic answer is: yes. The continuing search for ancient artifacts, documents, locations, and inscriptions has, for the most part, confirmed the accuracy of the New Testament gospels. In some cases, I'll supply an example below, archeology has helped to solve some of the perplexing riddles of New Testament interpretation.

Perhaps the best (and most interesting) way for me to illustrate the relevance of archeology to the gospels is to include several pictures and comment upon them. This is a tiny sample of what's available, but it does help to show how archeology aids our understanding of the gospels and supports our confidence in their reliability.

The Synagogue in Capernaum The gospels (for example, Mark 1:21) state (or imply) that Jesus taught in a synagogue in the town of Capernaum along the northwest short of the Sea of Galilee. The ruins of an ancient synagogue can be found in Capernaum, but it dates from the 4th century A.D. Yet beneath this synagogue archeologists uncovered the remains of a still earlier synagogue, one that can be dated to the first-century. In the picture to the right, the foundation of the oldest synagogue looks like rectangular, black stone under the existing ruins. (Photo Copyright © www.BiblePlaces.com.) |

|

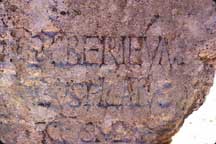

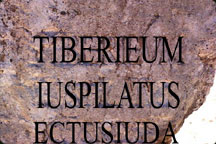

The Pilate Inscription In 1961, in Caesarea Maritima, where Pontius Pilate lived, an inscription was found which, among other things, confirms not only the rule of Pilate in Judea, but also his preference for the title "Prefect." The picture to the right shows the inscription. In the lower picture I've enhanced the text so you can see it more clearly. The Latin reads: Tiberium . . . [Pont]ius Pilatus [Praef]ectus Iudaeae, or Pontius Pilate Prefect of Judea. |

|

Bones of a Crucified Man Because most crucified people were crudely buried, or perhaps left for animals to devour, we don't have much archeological evidence of crucifixion in Judea, though nobody doubts that thousands of Jews were crucified by the Romans. In 1968, however, an ossuary (box filled with bones) was found in a cave at Giv'at ha-Mivtar in Jerusalem. This box contained the bones of a crucified man. The bones, with a nail still in place in the heels, have allowed scholars to learn more about the specific techniques of crucifixion employed by the Romans. |

|

The "Tribute Penny" All three synoptic gospels record an incident in which Jewish leaders set a trap for Jesus by asking Him whether the Jews ought to pay taxes to the emperor or not. Jesus asked them to show Him a coin, after which He said to give to God the things that are God's and to Caesar the things that are Caesar's. It's likely that the coin in this story was like the one pictured to the right. The inscription around the head of Tiberius reads in Latin: TI CAESAR DIVI AUG F AUGUSTUS = Augustus Tiberius Caesar Son of the Divine Augustus. That the coin referred to by Jesus accorded divinity to Augustus makes the story from the gospels more ironic. |

|

The Cliff at El Kursi In an earlier post I discussed the issues concerning the location of Jesus's casting out demons from a man into a herd of pigs, which then ran down a cliff into the Sea of Galilee. The gospels refer to the location of this event as in the country of the Gerasenes or Gadarenes. Yet Gerasa and Gadara are far from the Sea of Galilee. Recent investigations have focused on another town, known today as El Kursi. It was called Gergesa or Khersa in ancient times, which would have been spelled like Gerasa in Greek. An ancient church had been built in El Kursi on top of a site that was considered sacred because Jesus had done something important there. Archeologists found evidence of an ancient graveyard nearby (where the demonized man could have been living). Moreover, there is a steep cliff at El Kursi, down which the herd of pigs could have run. Though the jury is still out on this one, it looks as if the event depicted in the gospels happened, not at Gerasa or Gadara, but El Kursi. The evangelists referred, not to the city itself, but to the region in which it was found. (Note regarding the lower picture: It's unlikely that the barbed wire fence and powerline were there when Jesus visited.) |

|

Conclusion

While these five archeological examples don't prove anything specific about Jesus, they certainly show that the gospel records fit what we know from archeology about the world in which Jesus ministered. In this sense they confirm the reliability of the gospels.

But, you may be wondering, haven't I left out the archeological discoveries that are arguably most relevant to the study of the gospels and, in fact, most controversial? What about the Dead Sea Scrolls? What about the gospels discovered at Nag Hammadi? Don't the documents from these two sites undermine the reliability of the biblical gospels? Do these questions I'll turn in my next post.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Does Archeology Support the Reliability of the Gospels? Section B ![]()

Part 24 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Friday, October 28, 2005

In my last post I showed how archeology supports the general reliability of the gospels. But I did not address two major archeological finds which, it has been claimed, actually undermine the historicity of the biblical gospels. Perhaps the most popular proponent of this view is Sir Leigh Teabing, the fictional scholar in Dan Brown's novel, The Da Vinci Code. Here's what Teabing says about the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi Library:

"Fortunately for historians," Teabing said, "some of the gospels that Constantine attempted to eradicate managed to survive. The Dead Sea Scrolls were found in the 1950s hidden in a cave near Qumran in the Judean desert. And, of course, the Coptic Scrolls in 1945 at Hag Hammadi. In addition to telling the true Grail story, these documents speak of Christ's ministry in very human terms. Of course, the Vatican, in keeping with their tradition of misinformation, tried very hard to suppress the release of these scrolls. And why wouldn't they? The scrolls highlight glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications, clearly confirming that the modern Bible was compiled and edited by men who possessed a political agenda – to promote the divinity of the man Jesus Christ and use His influence to solidify their own power base." (p. 234)

Well that certainly lays down the gauntlet, doesn't it? So, is Teabing right? Do the scrolls found at the Dead Sea (actually, contra Teabing, in eleven caves beginning in 1947) and at Nag Hammadi (actually, they were codices, not scrolls) in Egypt in fact contain gospels that survived Constantine's purge? And do these gospels tell "the true Grail story"? And do they "speak of Christ's ministry in very human terms"? And do they "highlight glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications? And do they "clearly [confirm] that the modern Bible was compiled and edited by men who possessed a political agenda – to promote the divinity of the man Jesus Christ and use His influence to solidify their own power base"?

I'm tempted to save us all a lot of time and answer all of these questions with a simple No. The Da Vinci Code, after all, is a work of fiction. And Teabing's "history" of early Christianity is also mostly fictional. The problem is that this information is presented in the novel as if it were the recognized historical truth which sets the backdrop for the fictional aspects of The Da Vinci Code. And many readers, unfamiliar with the actual history of early Christianity, have taken Brown/Teabing's view as if it were in fact true. Of course they've been led to this conclusion by the first page of The Da Vinci Code, which reads: "FACT: . . . All descriptions of artwork, architecture, documents, and secret rituals in this novel are accurate." (p. 1). So we must deal with the question of whether or not what Teabing says about the Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS) and the Nag Hammadi Library (NHL) is, in fact, accurate, as Dan Brown claims.

Before I speak directly about the DSS and the books found at Nag Hammadi, I want to add a personal word. I spent a large amount of my time in graduate school studying the DSS and the NHL. One of my professors was on the original translation team for the DSS, and two of my professors were involved in the translation of the NHL. In one seminar I was required to read some of the unpublished DSS from photographs taken of the original scrolls, which if nothing else gave me lots of respect for those who did this for a living. I don't claim to be an expert on the DSS or on the NHL, but I'm quite familiar with these documents, and I have spent a lot of time interacting with those who are experts in this material.

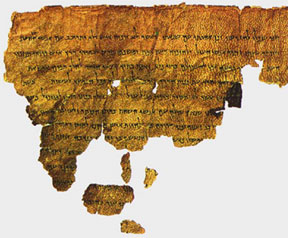

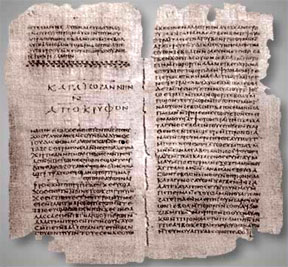

Do the Dead Sea Scrolls Undermine the Reliability of the Gospels? No. In fact they support it. First of all, the DSS are Jewish sectarian documents (including substantial portions of the Hebrew Bible) that do not mention Jesus or early Christianity. Yes, I'm aware that a few so-called scholars see Jesus secretly encoded into the DSS, but their theories haven't persuaded any serious scholars of the scrolls or of early Christianity. So one might be tempted to say that the DSS are irrelevant to the question of the gospels' reliability. But this would be a mistake. What the DSS reveal in great detail is the life and thought of a group of Jews more or less contemporaneous with Jesus and early Christianity. Whether Jesus Himself had contact with some of these people is debatable, though many scholars believe they influenced John the Baptist, who then influenced Jesus. Yet even if a connection this obvious didn't exist, the DSS help us to understand the Jewish world in which Jesus operated. They illustrate the variety of messianic expectations in the time of Jesus. And they show how Jesus's teaching fits within the Jewish world of first-century Palestine. Let me cite one example. Before the discovery of the DSS, it was common in some scholarly quarters to view the teaching of Jesus in the Gospel of John as thoroughly Hellenistic, and therefore unlikely to have come from Jesus Himself. But when the DSS were discovered, many of the supposedly Greek aspects of Jesus's teaching in John, like the contrast between darkness and light, were seen to be thoroughly at home in the Judaism of Jesus's own day. Hence, He could certainly have used dark vs. light imagery in His teaching. In this case, and there are many like it, the DSS confirm the reliability of the New Testament gospels in their portrayal of Jesus. |

|

|

In the middle of the picture above you see two black openings in the cliff. These are the entrances to Cave 4, one of the eleven caves near Qumran (by the Dead Sea) where ancient Jewish scrolls were found. (Picture thanks to Holy Land Photos). The picture below is a part of a scroll found in Cave 4. It's called "The Rule of the Community." Notice the scraps of the scroll beneath the larger piece. These were not found like this, of course, but were placed there by scholars who pored over thousands of scraps for decades. Imagine taking twenty large jigsaw puzzles, dumping all the pieces in one large pile, mixing them up, and then throwing out half of the pieces and all the boxes that show what the puzzles represent. Then try to put the pieces where they belong. This would be child's play compared to what the scroll scholars had to do. |

||

|

The DSS are extraordinarily important for the understanding of Jesus and early Christianity – truly a monumental find. Yet I'm not aware of anything in the DSS that undermines either the reliability of the gospels or orthodox Christianity. This means, by the way, that nothing in the DSS relates to the fictional claims of Leigh Teabing. There are no gospels among the DSS. No Grail story. No historical discrepancies. And nothing in the DSS speaks of Jesus Christ. Insofar as they help us to understand His world, however, they reinforce our confidence in the reliability of the gospels.

In my next post I'll address the NHL and its relevance to our understanding of the biblical gospels.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Does Archeology Support the Reliability of the Gospels? Section C ![]()

Part 25 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Monday, October 31, 2005

This is the third post in which I've considered the implications of archeology for our estimation of the reliability of the New Testament gospels. Last time I launched the conversation by quoting a passage from Dan Brown's novel, The Da Vinci Code. Here, once again, is the passage:

"Fortunately for historians," Teabing said, "some of the gospels that Constantine attempted to eradicate managed to survive. The Dead Sea Scrolls were found in the 1950s hidden in a cave near Qumran in the Judean desert. And, of course, the Coptic Scrolls in 1945 at Hag Hammadi. In addition to telling the true Grail story, these documents speak of Christ's ministry in very human terms. Of course, the Vatican, in keeping with their tradition of misinformation, tried very hard to suppress the release of these scrolls. And why wouldn't they? The scrolls highlight glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications, clearly confirming that the modern Bible was compiled and edited by men who possessed a political agenda – to promote the divinity of the man Jesus Christ and use His influence to solidify their own power base." (p. 234)

In my last post I considered the relevance of the Dead Sea Scrolls to the New Testament gospels. Though they have much to tell us about the world in which Jesus lived, the Dead Sea Scrolls contain no gospels, and no information about Jesus. Thus, though they are relevant to the study of early Christianity, they do none of the things claimed by Teabing/Brown.

So what about the documents (codices or books, not scrolls) from the Nag Hammadi library (NHL)? Do these "speak of Christ's ministry in very human terms"? Do they "highlight glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications"? Do they clearly confirm "that the modern Bible was complied and edited by men who possessed a political agenda"? In sum, do the documents from Nag Hammadi undermine our confidence in the reliability of the New Testament gospels?

Do the Nag Hammadi Codices Undermine the Reliability of the New Testament Gospels?

Unlike in the case of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Dan Brown's fictional Leigh Teabing has a chance at being correct when he talks about the NHL. The codices from Nag Hammadi in Egypt do contain a number of "gospels," and these do contain a picture of Jesus which, for the most part, diverges from what we find in the New Testament. (In some ways, the Gospel of Thomas, the most important of the NHL gospels for the study of Jesus, actually supports the New Testament gospels, though its picture of Jesus is quite different from their's in some ways.)

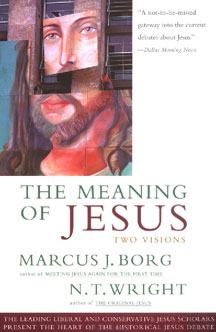

| According to the Brown/Teabing thesis, the NHL documents tell "the true Grail story" and "speak of Christ's ministry in very human terms." In fact they have virtually nothing to say about "the true Grail story" as it's presented in The DaVinci Code. The claim that the gospels from the NHL reveal Jesus's secret marriage to Mary Magdalene depends on a misinterpretation of two passages from the library, passages that constitute less than one-tenth of one percent of the whole NHL. For an in-depth analysis of the documents themselves, see my series: Was Jesus Married? |  |

|

A picture of the Nag Hammadi codices, discovered in 1945. |

||

Moreover, if you were to spend an hour or so perusing the NHL, you'd might be surprised by the picture of Jesus you found. Far from presenting a more human Jesus, as claimed by Teabing/Brown, the Nag Hammadi documents actually portray a much less human Jesus than the one we find in the New Testament gospels. The Nag Hammadi Jesus comes across as a very odd, other-worldly revealer, hardly the fully human being we find in the New Testament. This makes perfect sense, of course, since the NHL was collected by a group of Gnostics, who denied the value of the flesh and looked for a non-fleshly "spiritual" revealer/redeemer. They didn't value the human Jesus, but rather than spiritual, non-physical "Christ" or "Savior."

Here are a few passages from some of the gospels of the NHL. These illustrate the kind of Jesus found there:

From the Gospel of Truth:

The gospel of truth is a joy for those who have received from the Father of truth the gift of knowing him, through the power of the Word that came forth from the pleroma – the one who is in the thought and mind of the Father, that is, the one who is addressed as the Savior, (that) begin the name of the work he is to perform for the redemption of those who were ignorant of the Father, while the name [of] the gospel is the proclamation of hope, being discover for those who search for him. (Gospel of Truth, I 16:31-17:4).

From the Gospel of Thomas:

Jesus said to [Salome], "I am He who exists from the Undivided. I was given some of the things of My father."

[Salome said,] "I am Your disciple."

[Jesus said to her,] "Therefore I say, if he is undivided, he will be filled with light, but if he is divided, he will be filled with darkness." (Gospel of Thomas 61).

From the Gospel of Philip:

[The Lord said,] "The world came about through a mistake. For he who created it wanted to create it imperishable and immortal. he fell short of attaining his desire. For the world never was imperishable, nor, for that matter, was he who made the world." (Gospel of Philip, 75:2-9)

From the Gospel of Mary (Magdalene):

[Mary said,] "What is hidden from you I will proclaim to you." And she began to speak to them these words: "I," she said, "I saw the Lord in a vision and I said to him, 'Lord, I saw you today in a vision.' He answers and said to me, 'Blessed are you, that you did not waver at the sight of me. For where the mind is, there is the treasure.' I said to him, 'Lord, now does he who sees the vision see it [through] the soul [or] through the spirit?' The Savior answered and said, 'He does not see through the soul nor through the spirit, but the mind . . . .'" (Gospel of Mary 10:7-21).

Lest you think I chose the oddest passages from the NHL, I'd encourage you to check for yourself. If you really want a wild ride, read portions of The Thunder, Perfect Mind or the Trimorphic Protennoia. Then, if you really want to stretch your mind, check out this part of the Gospel of the Egyptians:

After you've spent some time actually reading the documents from Nag Hammadi, the notion that they "speak of Christ's ministry in very human terms," as claimed by Teabing/Brown, will strike you not only as wrong, but also as verging on the ridiculous.Domedon Doxomedon came forth, the aeon of the aeons, and the throne which is in him, and the powers which surround him, the glories and the incorruptions. The Father of the great light who came forth from the silence, he is the great Doxomedon-aeon, in which the thrice-male child rests. And the throne of his glory was established in it, this one on which his unrevealable name is inscribed, on the tablet [...] one is the word, the Father of the light of everything, he who came forth from the silence, while he rests in the silence, he whose name is in an invisible symbol. A hidden, invisible mystery came forth: iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii EEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE oooooooooooooooooooooo uuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu eeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa OOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO. (Gospel of the Egyptians 43:9-44:9)

So, then, do the NHL gospels "highlight glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications"? Since this post is running rather long, I'll save my answer for tomorrow. Stay tuned . . . .

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Does Archeology Support the Reliability of the Gospels? Section D ![]()

Part 26 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Tuesday, November 1, 2005

In yesterday's post I began examining the relevance of the Nag Hammadi Library (NHL) for our estimation of the reliability of the New Testament gospels. For the sake of argument, I was responding to a claim made by Sir Leigh Teabing, a fictional character in Dan Brown's novel The Da Vinci Code. Here, once again, is the passage:

"Fortunately for historians," Teabing said, "some of the gospels that Constantine attempted to eradicate managed to survive. The Dead Sea Scrolls were found in the 1950s hidden in a cave near Qumran in the Judean desert. And, of course, the Coptic Scrolls in 1945 at Hag Hammadi. In addition to telling the true Grail story, these documents speak of Christ's ministry in very human terms. Of course, the Vatican, in keeping with their tradition of misinformation, tried very hard to suppress the release of these scrolls. And why wouldn't they? The scrolls highlight glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications, clearly confirming that the modern Bible was compiled and edited by men who possessed a political agenda – to promote the divinity of the man Jesus Christ and use His influence to solidify their own power base." (p. 234)

Question: Do the Nag Hammadi documents (codices, not scrolls) "highlight glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications" when they're compared with the New Testament gospels?

Yes, they do, in a sense. The dominant picture of Jesus in the NHL differs considerably from the dominant picture of Jesus in the New Testament. If one image is historical, then the other isn't. And if one is authentic, then the other is fabricated. The key question is: Which picture of Jesus is most likely to be the historically accurate one? The key answer is: The picture found in the New Testament gospels.

Why do I say this? First of all, the New Testament gospels were written within 30 to 60 years after the death of Jesus. The NHL gospels, with the possible exception of Thomas, were written at least 100 years after Jesus, with some more than 150 years later. Moreover, the only gospel in the NHL that could be construed (however wrongly, I believe) to support the Brown/Teabing view of Jesus as Mary Magdalene's husband was written at least 200 years after Jesus died. So, not only are the New Testament gospels much older than the Nag Hammadi documents, but also, as I have shown earlier in this series, the New Testament gospels utilized earlier written sources and public oral traditions. Thus, in the race for historical reliability, the biblical gospels have lapped the NHL gospels more than once. |

|

|

This picture is of a portion of the Nag Hammadi Library. It shows the beginning of the Apocryphon of John, which begins: "The teaching [of the savior] and [the revelation] of the mysteries [and the] things hidden in silence, [all these things which] he taught John, [his] disciple." (II, 1: 1-4) |

||

Furthermore, the picture of Jesus in the NHL bears little resemblance to anything that fits within first-century A.D. Jewish life. Their vision of a Gnostic redeemer reflects the Hellenistic milieu in which the NHL gospels were written. So, any "glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications" will be found, not in the New Testament gospels, but in the gospels of the NHL. Thus the Teabing/Brown thesis is partly right, in that there are "discrepancies and fabrications," but completely wrong in its estimation of which gospels are credible and which are fictional.

I don't mean to suggest, however, that the NHL is not an invaluable find. It allows us to understand Christian Gnosticism with unprecedented insight. But the NHL has little to offer to the quest for the historical Jesus, apart from what might be gleaned from the Gospel of Thomas and a few other passages in the NHL that may be traceable through oral traditions back to Jesus Himself.

In summary, nothing in the Dead Sea Scrolls (as I showed in Part 24) or the Nag Hammadi Library undermines the reliability of the biblical gospels. In fact, the opposite is true. The Dead Sea Scrolls help us understand the world of Jesus, and they illustrate how well the Jesus of the New Testament gospels fits within that world, in contrast to the Jesus of the non-canonical gospels. Comparing the "Jesus" found in the Nag Hammadi Library with the Jesus found in the New Testament underscores the realism of the biblical gospels and their portrayal of a truly human, Jewish Jesus, unlike the other-worldly Redeemer of the Gnostic gospels.

Dan Brown's fictitious Sir Leigh Teabing made one more claim about the New Testament documents. Let me quote once again:

"The scrolls highlight glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications, clearly confirming that the modern Bible was compiled and edited by men who possessed a political agenda – to promote the divinity of the man Jesus Christ and use His influence to solidify their own power base." (p. 234)

Though I've shown that the scrolls (and Nag Hammadi codices) don't highlight anything of the kind, what about the notion that the Bible was "complied and edited by men" with an agenda? Were the New Testament gospels written, edited, preserved, and canonized to promote the divinity of Jesus and thereby to solidify the power base of the orthodox Christian church? I'll begin to address this scenario in my next post.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Do the Gospels Reflect the Political Agenda of the Early Church?

Section A ![]()

Part 27 of the series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Wednesday, November 2, 2005

Several times recently I've used portions of Dan Brown's novel, The Da Vinci Code, as a discussion partner for my examination of the reliability of the New Testament gospels. I have done so, partly because so many readers have taken Brown's fictitious "history" to be genuine, and also because Brown, as an engaging author, has a compelling way of putting the case against the New Testament gospels.

When I finished my last post, I quoted an objection that Brown puts on the lips of Sir Leigh Teabing, a character who "reveals" the truth about Jesus and the gospels. A part of this truth, according to Teabing, is:

"The [Dead Sea Scrolls and Nag Hammadi documents] highlight glaring historical discrepancies and fabrications, clearly confirming that the modern Bible was compiled and edited by men who possessed a political agenda – to promote the divinity of the man Jesus Christ and use His influence to solidify their own power base." (p. 234)

What is the implication of this for those of us who have learned about Jesus through the biblical gospels? Teabing states bluntly: "What I mean . . . is that almost everything our fathers taught us about Christ is false." (p. 235).

I've shown in my last two posts that the attempt of Teabing/Brown to use the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi Library to prove the case against the New Testament gospels is unpersuasive. But it's still possible that the people who edited, and even who wrote, the biblical gospels were guided by an agenda that led them to compromise or even to hide the truth. In fact, we see this very thing happening in early Christianity and its "gospels."

Second-Century Tampering with the Traditions About Jesus

We have ample evidence that early Christians, or at least those who considered themselves to be Christians, tampered with the historical traditions about Jesus to fit their particular agendas. For example, in the mid-second century there was a man named Marcion. He claimed to be a Christian, and was an influential thinker and writer who emphasized the discontinuity between Judaism and Christianity. Thus he rejected the gospels of Matthew, Mark, and John as being too Jewish, and included in his "canon" only a trimmed-down version the Gospel of Luke. This version was pruned of its Old Testament references. Though Marcion regarded himself as a true Christian, in fact he was denounced by the orthodox church as a heretic. His views were not adopted by the church, though, ironically enough, he may have forced the church to identify four authoritative gospels in a more clearly defined "canon" of Scripture. At any rate, Marcion's editing and treatment of the gospels clearly reflected his agenda.

We can also see self-proclaimed Christians reshaping history to fit their agendas in many of the non-canonical gospels. For example, the Gospel of Peter, written sometime in the second century A.D., cleans up the account of Jesus's death in a couple of ways. First, it tends to exonerate the Romans and Pontius Pilate, while putting full blame for the death of Jesus on the Jews. This, of course, would nicely accommodate the Christian situation in the second century. Second, the Gospel of Peter takes away the scandal of the cross by revealing that Jesus remained silent on the cross "as having no pain." This also reflects the Hellenistic world in which early Christianity was growing and its tendency to devalue the flesh. Yet, because of its rejection of the full humanity of Jesus, the Gospel of Peter was rejected by the orthodox church as heretical. To cite one further example of Christians tampering with the history of Jesus, in the Infancy Gospel of Thomas the boy Jesus makes twelve clay sparrows on the Sabbath. When his father rebukes him for doing what is not lawful on the Sabbath, Jesus commands the clay sparrows to fly away, which they do, much to the surprise of Joseph. Clearly such stories in the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, a second-century composition, reflect the desire of some Christians to have fantastic stories about little Jesus, just as the Greeks had such stories about their gods. Alas, the Infancy Gospel of Thomas was also rejected by the orthodox church as heretical. So the Brown/Teabing notion of agenda-driven editing of the gospels isn't crazy. But it tends to be found in second-century and later literature. (Ironically, this is the literature from which Brown/Teabing derive the marriage of Jesus.) Yet, by analogy, we might wonder if this same sort of thing was going on in the first century, when the canonical gospels were written. By the way, I've focused once again on the non-canonical gospels so you can get a better sense of what's actually in this literature. As you can see from the examples I've surveyed above, the Jesus found in the extra-biblical gospels is usually much less human and much more super-human than the Jesus of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, who was truly born, who was truly tired at times, who truly struggled with his divine calling in Gethsemane, who truly suffered, and who truly died. When it comes to a human Jesus, I'll take the canonical gospels over the non-canonical ones any day. |

|

|

Anne Rice, the best selling author of vampire books, has just published a new novel: Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt. I have not read this book (though I have ordered it). Apparently it reflects Rice's conversion to Christianity. It also is a result of careful study of Jesus and his time of history. According to a Beliefnet interview of Rice, she takes a dim view of the hyper-skepticism of much modern scholarship on the gospels. Her book does include legendary Jesus material like the clay bird story, but Rice seems to understand the difference between fact and fiction. |

||

Nevertheless, do we find in the biblical gospels the sort of agenda-driven editing that we find in the non-canonical gospels? And did this agenda have to do with power, as claimed by Brown/Teabing?

The Gospels Out of Synch with the Agenda of the Early Church

I've already explained that the four evangelists did have what we might call a theological or pastoral "agenda." And I've also argued that this "agenda" actually led them to care about historical accuracy as determined according to the standards of their time. (See three earlier posts in this series, beginning with the first "If The Gospels are Theology, Can They Be History?") Further support for this thesis comes from the fact that the biblical gospels are often out of synch with the needs and concerns, indeed, the agenda of the early church.

For example, if one supposes that the early Christians made up sayings of Jesus to address current concerns, then it's hard to figure why they didn't do a much better job of it. So many of the conflicts and challenges faced by the early church were never addressed by sayings Jesus, for example: the question of speaking in tongues; the issue of women in leadership; etc.

Moreover, some of the sayings of Jesus that were passed on orally and then incorporated into the gospels made matters more complicated for the early church, not less. For example, if anything characterized early Christianity, it was an evangelistic zeal that included the Gentiles. Yet some of the sayings of Jesus in the gospels seem, at first glance, to be contradictory to this very mission (see Matt 10:5, Mark 7:24-30). If the writers and editors of the gospels were motivated by their agenda to play fast and loose with history, surely they would have improved upon or even eliminated things in the Jesus tradition that were awkward. Yet this didn't happen with the New Testament gospels.

In fact, certain elements of the biblical gospels seem to undermine the political agenda – if you want to call it that – of the early church, rather than supporting it. I'll turn to these elements in my next post.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Do the Gospels Reflect the Political Agenda of the Early Church?

Section B ![]()

Part 28 of the series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Thursday, November 3, 2005

If you've been following this series for a while, you know that I've been responding to a charge that's found on the lips of Sir Leigh Teabing, a fictional character in Dan Brown's novel The Da Vinci Code. Yet Teabing expresses a view that is proposed, not just in imaginative novels, but also among certain scholars who discount the reliability of the New Testament gospels. In this post I want to continue to respond to the charge that "the modern Bible was compiled and edited by men who possessed a political agenda – to promote the divinity of the man Jesus Christ and use His influence to solidify their own power base," and that for this reason "almost everything our fathers taught us about Christ is false." (Da Vinci Code, pp. 234, 235).

There are many reasons to reject this Teabing/Brown thesis. For one thing, if you've read much of this blog series, you realize that there are lots of reasons to believe that what the biblical gospels teach us about Jesus is substantially true. For another, if the main point of the New Testament gospels was "to promote the divinity of the man Jesus Christ," then the gospels, apart from John, did a pretty mediocre job at best. Oh, don't get me wrong. I believe that we can see Jesus's deity in the pages of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. But you've got to admit that, apart from a few unusual moments (Jesus's conception, The Transfiguration, etc.), the biblical gospels present the Jesus primarily as an inspired human being, not as God in the flesh. If Matthew, Mark, and Luke were willing to twist history or make up material in order to clarify Jesus's divinity, don't you think they might have added a saying or two in which Jesus actually said, "Verily, verily I say unto you: I'm God."

The gospels also present aspects of Jesus's life and ministry that, it would seem, editors bent on emphasizing his divinity would have minimized or eliminated. Sometimes, for example, Jesus appears not to be omniscient, as when He asked "Who touched me?" (Luke 8:45) or admitted that He didn't know the time of His return (Mark 13:32). In other cases His healing powers seem oddly limited (Mark 6:1-6). And then there's the astounding picture of Jesus in Gethsemane, which, though moving for Christians, doesn't exactly portray Jesus as a god (Mark 14:32-42). Finally, of course, there's the utterly scandalous presentation of Jesus's crucifixion, which was a huge stumbling block to acceptance of Jesus as divine in the Hellenistic world. Many of the Gnostic gospels, which were agenda-driven, got rid of the scandal of the cross by ignoring it or by denying that Christ actually suffered. The biblical gospels held onto the scandal of the cross. A Most Curious Inconsistency There's yet another facet of New Testament gospels that disproves the Teabing/Brown thesis. This, for me, is one of the most powerful arguments in favor of the reliability of the gospels, even as it's a persuasive rebuttal to the "it was all about the power of the church" thesis. And, interestingly enough, this facet doesn't even concern Jesus directly. Allow me to explain. |

|

|

This classic portrayal of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane was painted by Heinrich Hoffmann. |

||

According to the Teabing/Brown thesis, the writing, editing, and collecting of the New Testament gospels was primarily about power. All of this reflected the effort of the orthodox church to establish power, especially over rival heretical groups, like the Gnostics. There was indeed a power struggle within Christendom in the second and third centuries. And the orthodox church did indeed claim, among other things, the power to teach the truth about the ministry and nature of Jesus. One of the church's key arguments was that their sacred writings, their ecclesiastical leaders, and their basic beliefs were apostolic. The writings were either written by the first disciples of Jesus (including Paul) or by their associates, and were consistent with apostolic teaching. The bishops could trace their authority back to the earliest disciples of Jesus, so their leadership was also apostolic. And what the orthodox church believed was consistent with the essence of the apostles' teaching. (Hence, many churches use the "Apostles' Creed" even today, an early Christian summary of apostolic doctrine.)

Given the centrality of the apostles, especially the first disciples of Jesus, in the church's claim to rightful authority, it's fascinating and telling to note how the disciples of Jesus are actually portrayed in the New Testament gospels. They are, after all, the first leaders of the church. They are the ones from whom the church draws its power. Yet they are the ones whom the gospels portray as . . . well . . . faithless, foolish, and unreliable. Not exactly what you'd expect from gospels that were written and/or edited to undergird the power of the orthodox church!

The disciples of Jesus are first seen in a positive light, as they leave their familiar lives behind to follow Jesus (Mark 1:16-20). But things go downhill quickly from there. For example:

• The disciples consistently misunderstand Jesus (e.g. Matt 16:5; Mark 10:13-14, 35-40; John 12:17).

• They are self-seeking, concerned for their own greatness and glory (Mark 9:34, 10:35-37).

• They lack faith in God or Jesus (e.g. Matt 8:26; Matt 14:22).

• They are rebuked by Jesus for being people "of little faith" (Matt 8:26). Worse still, Jesus once expresses His exasperation over the disciples, "You faithfulness and perverse generation, how much longer must I be with you?" (Matt 17:17).

• They abandon Jesus in his hour of greatest need, sleeping while He asks them to join Him in prayer at Gethsemane (Mark 14:32-43). Then, when He is arrested, all of them desert Jesus and run away to save their own necks (Mark 14:50). None of the male disciples is present at the cross, except for "the disciple whom Jesus loved" (perhaps John, John 21:20).

• After the resurrection, the disciples disbelieve Mary's report that He is risen (Luke 24:11) and some doubt (or are hesitant) even when they see the risen Christ (Matt 28:17).

If you read through the four biblical gospels, you'll find that the disciples are almost never pictured in a positive light, as paragons of faith or wisdom. Yet time and again they're portrayed negatively. This fact, all by itself, seems to me to disprove the Teabing/Brown thesis. Moreover, it strongly suggests that the early Christian tradition and the four evangelists were willing to pass on the truth, even if that truth portrayed their founding leaders (after Jesus, of course) in such an embarrassing light.

There is an even more surprising aspect to this argument, one that puts the final nail in the coffin of the "ecclesiastical power grab" thesis. I'll pursue this in my next post.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Do the Gospels Reflect the Political Agenda of the Early Church?

Section C ![]()

Part 29 of the series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Friday, November 4, 2005

In my last post I was responding to the idea that the New Testament gospels were written, edited, collected, and preserved as a power grab by the early church. I showed how this theory fails to make sense of many features of the gospels, including their negative portrayal of the disciples of Jesus. Since the disciples were the ones upon which the power of the orthodox church was based, if the power-grab theory were correct, then you'd expect to see the gospels portray the disciples as paragons of faith and wisdom, the sort of people upon whom to base a church. But, in fact, the New Testament gospels picture the disciples as faithless, foolish, and unreliable. In a phrase, they don't get it.

What I've just explained is sufficient to disprove the "power grab" theory of gospel formation and collection. But there's even more impressive evidence against this theory. Remember that the church that supposedly played fast and loose with the gospels derived its authority, not only from the apostles in general, but also from Peter in particular. He was, after all, the "rock" upon which Jesus promised to build His church (Matthew 16:18). And he was believed to be the first bishop of the Roman church, that is, the first pope.

So how does Peter fare in the New Testament gospels? Worse than the rest of the disciples. He's outstanding for his foibles, especially in crucial moments of Jesus's ministry. Let me cite a few examples:

• In Matthew 14:22-33, the disciples of Jesus are in a boat on the Sea of Galilee. Jesus comes to them from the shore, walking on the water. Peter gets out of the boat in order to approach Jesus. An exemplar of faith? Hardly, because he becomes frightened and starts to sink, crying out to be saved. Jesus refers to his as one with "little faith."

• Though Peter rightly confesses Jesus as the Messiah (Mark 8:27-33), he doesn't really understand what he's saying. So when Jesus reveals the necessity of His death, Peter actually rebukes Him. Jesus responds to Peter by saying, "Get behind me, Satan! For you are setting your mind not on divine things but on human things" (Mark 8:32-33).

• Peter doubly misunderstands the point of Jesus's foot washing, both in not wanting it and then in wanting too much washing (John 13:5-10).

• Peter is obviously special to Jesus since Jesus takes him along to the Garden of Gethsemane. But then Peter, along with two other disciples, keeps falling asleep rather than staying awake in Jesus's hour of turmoil. This is shown to be deeply distressing to Jesus (Mark 14:32-42).

If you haven't read through the biblical gospels recently, you might think that I've picked only those passages about Peter that show him in a poor light, while ignoring the ones that show him as a strong, wise leader, the kind of leader upon which Jesus would build the Roman Catholic Church. In Acts of the Apostles Peter emerges as this sort of leader, but only because the Holy Spirit fills him with power. The gospels don't paint a flattering portrait of Peter at all. |

|

|

This is the inside of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, the center of the Roman Catholic Church and an astounding monument to the memory of Peter. |

||

Can you imagine a movement that allowed such stories of a prominent founder to be told, even to be enshrined in its foundational documents? Usually a movement would make every effort to cover up the failings of its first leaders, to rewrite history in a more flattering way. For example, the official website of the Mormon Church includes a historical summary of the life of its founder, Joseph Smith. In this summary it's mentioned that Smith married Emma Hale on January 18, 1827. It is not mentioned, however, that Emma was the first of many wives of Joseph Smith, who believed that God had commanded the practice of plural marriage. One historian argues that Smith had thirty-three wives. Yet this is neatly left off of the Mormon website, for very understandable reasons. (The website does still contain, however, Section 132 of the Doctrine and Covenants, in which God purportedly reveals to Joseph Smith His commandment for men to have multiple wives. And in a Frequently Asked Question section it's acknowledged that Joseph Smith obeyed God's command to practice plural marriage. But none of this shows up in the biographical material on Smith.)

I think the presentation of Peter in the New Testament gospels shows the folly of the "power grab" theory of gospel production and authentication. But it also shows something quite astounding about early Christian oral tradition and the writing of the gospels. Those who passed on and wrote down the actions and sayings of Jesus were committed to telling the truth, even when this truth was embarrassing to some of the most prominent leaders of the early church. Surely it was only a strong commitment to historical accuracy that kept such a negative portrayal of the disciples, including Peter, in the New Testament gospels.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Closing Thoughts: On the Gospels and Faith ![]()

Part 30 of the series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Monday, November 7, 2005

With today's post I bring to an end this series on the reliability of the New Testament gospels. I must confess that when I started this series 37 days ago I was not expecting that it would end up with 30 parts. This is now my longest blog series on record, consisting of more than 35,000 words. Yikes! If you've been reading along, not only do you deserve some kind of prize, but also you know that I've simply been following a chain of thought to its logical (I hope) conclusion. Now I'm finally to the end of the chain, at least for now.

I do not believe that I've proven beyond a reasonable doubt that the New Testament gospels are historically reliable. In the end, I'm not sure that the "Evidence that Demands a Verdict" approach works with the gospels, though I'm not criticizing those who use this apologetic. Historical arguments about the 2,000-year-old past, it seems to me, are too complex and convoluted for verdicts declared with a ring of certainty.

Ironically, these days it's often the skeptical scholars who seem to have cornered the market on certainty. And as long as they write mainly for each other, and talk mainly to each other, and make sure their scholarly publications and meetings are dominated by each other's work, these skeptical scholars can pretend as if their "assured results of scholarship" are rock solid. In fact, however, they're often more like a house of cards built on the sand, if you'll pardon a badly-mixed metaphor.

I don't object to scholars holding views that doubt or even deny the reliability of the gospels. But I do object to scholars holding these views without ever taking seriously the evidence that would challenge or contradict them. This seems not only disingenuous, but also bad scholarship. I'm also concerned, however, that some conservative scholars are too quick to disregard the insights of critical scholars. For the most part, however, conservative scholars must deal with a broad range of scholarly input, while skeptical scholars can remain safely protected within their conveniently narrow worlds. If, for example, you're an evangelical New Testament scholar, you've got to interact with the Jesus Seminar material. If you're a fellow in the Jesus Seminar, you can have a successful academic career while pretending that credible conservative scholarship doesn't exist.

I first discovered this fact when I was a graduate student at Harvard, doing a Ph.D. in New Testament. Our reading lists almost never included conservative or evangelical scholarship, but were filled with hyper-critical German and Anglo texts. One time while I was home on vacation I went to the Fuller Seminary library to see if I could find some of my required readings. (Fuller is an evangelical seminary with a high view of biblical authority, though not high enough for some evangelicals!) What I found shocked me. On the reserve reading shelves for Fuller New Testament classes I saw many of the critical books from my Harvard list, as well as solid evangelical books. It was obvious to me that the Fuller student was being exposed to a much broader range of ideas than I was at Harvard. I wondered when "liberal" scholarship became so illiberally narrow.

There are some skeptical Jesus scholars who do take seriously more conservative work. One of the things I like about Marcus Borg, perhaps the most prolific and popularly-influential fellow of the Jesus Seminar, is his willingness to engage in serious dialogue with N.T. Wright, a critical scholar who has come to many conservative conclusions about Jesus. (I highly recommend the book they have written together: The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions.) But, in my experience, Borg is unusual in this regard. I mentioned above that I don't believe I've proved beyond a reasonable doubt that the New Testament gospels are historically reliable. I do believe, however, that I've shown it is reasonable to regard these gospels as historically accurate. Though I freely admit that certain elements of the gospels are problematic in this regard, I find that the evidence, when taken as a whole, strongly supports the view that the biblical gospels paint a reliable picture of Jesus (or, to be more precise, several accurate, complementary pictures of Jesus). |

|

As I've explained before, if your worldview excludes the possibility of miracles, then you have an intractable problem with the historicity of the gospels. But your acceptance of such a worldview is a matter of faith. There's no way you can prove that miracles don't happen, even as there's no way I can prove that the extraordinary events Christians believe to be miracles are actually works of God. There's an irreducible element of faith on both sides of this argument.

Nevertheless, my point is that one can approach the New Testament gospels as a theist and come up with a reasonable understanding of what happened: of who Jesus was and how early Christianity developed. Of course I believe that this understanding is not only reasonable, but in fact the most reasonable. Yet I'm willing to debate the pros and cons with those who disagree with me. What I'm unwilling to do is to accept the tyranny of "the modern scientific worldview," or to agree that historians must write as if miracles never happen, no matter what they might believe in their hearts. I'm happy to take my theistic understanding of the gospels and lay it beside all other options for careful scrutiny. At the very least, I think a fair observer would have to acknowledge that what I've proposed is reasonable, even if that observer isn't convinced. (By the way, let me hasten to add that what I've proposed depends upon the work of many, many scholars. A few ideas in this series are, as far as I know, unique to me. Most reflect the helpful efforts of many others, especially folk like F. F. Bruce, Craig Blomberg, N.T. Wright, and Ben Witherington.)

Throughout most of this series I've spoken of the gospels as reliable, meaning "reliable as historical sources of information about Jesus." Yet I believe, now speaking as a Christian more than as an historian, that the gospels are much more reliable than this. Aside from being trustworthy history, the gospels are also trustworthy revelation. I believe that the very Spirit of God inspired and guided the writers of the gospels. This means the portrayal of Jesus in Mark, for example, isn't only historically reliable. It's also God's way of helping us to know who Jesus really is.

Now I freely admit that what I'm saying here goes beyond historical inquiry. Yet I want to emphasize that what I have found as an historian doesn't imply that my faith in the inspiration of the gospels is really just wishful thinking. On the contrary, the more I study the New Testament gospels in the context of the literature and culture of their own time and place, and the more I compare these biblical gospels to the non-canonical varieties, the more I am persuaded that Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are indeed reliable both as historical records of Jesus and as trustworthy facets of divine revelation.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |