Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Volume 2 of 3 (printer-friendly version)

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com. Thank you.

Jesus Revealed: Know Him Better to Love Him Better, by Mark D. Roberts

Please pardon some shameless self-promotion, but I really do think this book has something to offer. Jesus Revealed examines many names and titles of Jesus (Son of God, Son of Man, etc.), explaining their historical, theological, and personal significance. Plus, I've added an appendix that answers the question "Was Jesus Married?" This book includes study questions for personal or group study. I've heard that it's helpful been helpful in adult classes and small groups. For more information or to purchase, click here.

What Difference Does It Make That There are Four Gospels?

Section B ![]()

Part 11 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Monday, October 10, 2005

In my last post I explained how the existence of the four New Testament gospels allows us to evaluate their testimony about Jesus, much as a jury would evaluate multiple witnesses to an event. I also noted the recent tendency among New Testament scholars to highlight, perhaps even to exaggerate, the differences (read "contradictions") between the gospels.

Now I freely grant that there are significant differences between the four biblical gospels on a number of key topics. For example, Matthew alone tells the story of the Magi's visit to the child Jesus, while Luke alone has shepherds abiding in the fields keeping watch over their flock by night. I plan to discuss the significance of these and other differences in future posts. But, for now, I want to focus on something that is often overlooked by scholars, but is generally acknowledged by careful readers who have lots of common sense: the striking similarities between the pictures of Jesus found in the New Testament gospels.

Here is a list of some of the details about Jesus's life and ministry that are found in all four gospels:

• Jesus was a Jewish man.

• Jesus ministered during the time when Pontius Pilate was prefect of Judea (around A.D. 27 to A.D. 37).

|

|

|

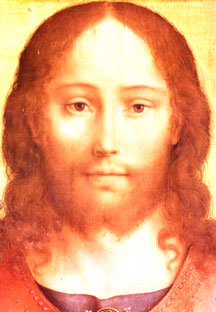

Talk about different pictures of Jesus! The top painting is by the 16th century Flemish painter, Joos van Cleve. The bottom is a painting on silk by an anonymous Chinese painter from the late 19th or early 20th century. |

||

|

• Jesus did various sorts of miracles, including healings and nature miracles.

• Jesus called people to have faith in Him and in God.

• Jesus was misunderstood by many, including his own disciples.

• Jesus experienced conflict with many Jewish leaders, especially the Pharisees and ultimately the temple-centered leadership in Jerusalem.

• Jesus spoke and acted in ways that undermined the temple in Jerusalem.

• Jesus spoke and acted in ways that implied He had a unique connection with God.

• Jesus was crucified at the time of Passover, under the authority of Pontius Pilate, and with the cooperation of some Jewish leaders in Jerusalem. (There are quite a few more details concerning the death of Jesus that are shared by all four gospels.)

• Jesus was raised from the dead on the first day of the week (Sunday).

• Women were the first witnesses to the evidence of Jesus's resurrection. (This is especially significant, since the testimony of women was not highly regarded in first-century Jewish culture. Nobody would have made up stories with women as witnesses if they wanted them to gain ready acceptance.)

This is certainly an impressive list of similarities shared by all four gospels. It's especially significant because I've included the Gospel of John here, even though it is the most distinctive among the biblical gospels. I believe, in light of this list, that it would be correct to say that, though the four gospels paint Jesus from different perspectives and in different tones, they are painting what is essentially the same picture. They agree on the most important points about Jesus's life and ministry, not to mention His death and resurrection. Moreover, they agree on the core of the early Christian message, that which came to be called the gospel, and ended up giving the four biblical gospels their name.

In my next post I want to examine in greater detail some of the distinctive elements of the individual gospels. Do these count against the historical reliability of the documents?

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Are There Contradictions in the Gospels? Section A ![]()

Part 12 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Tuesday, October 11, 2005

In my last post I showed that the four New Testament gospels agree considerably in their depictions of Jesus. In fact, the same essential aspects of Jesus's ministry can be found in any of the gospels. But that is not to say that the gospels tell exactly the same story in exactly the same way. In fact, each gospel views Jesus from a distinctive perspective, and provides unique insight into His ministry. This means, of course, that there are many variations between the New Testament gospels.

I just used the word "variations" to describe differences between the gospels. Others would use language that carries a more negative connotation. When I was in graduate school, my professors tended to speak, not of variations among the gospels so much as discrepancies or disparities. In some circles, you'll often hear about the disagreements among or the contradictions between the gospels. For example, last December, TIME Magazine ran a cover story on the birth of Jesus (subscription only). This article stated:

Matthew and Luke diverge in conspicuous ways on details of the event. In Matthew's Nativity, the angelic Annunciation is made to Joseph while Luke's is to Mary. Matthew's offers wise men and a star and puts the baby Jesus in a house; Luke's prefers shepherds and a manger. Both place the birth in Bethlehem, but they disagree totally about how it came to be there.

What TIME rightly shows are the variations in the nativity stories of Matthew and Luke. But it wrongly adds that the two gospels "disagree totally" about how the birth came to be in Bethlehem.

When I last checked, disagreement or contradiction involves specifically denying something someone else has said. Saying something different isn't disagreement, unless of course two things couldn't both true. So the fact that Matthew has Magi and Luke has shepherds in a genuine difference, but not a contradiction. It would be a contradiction if Luke placed the birth of Jesus in Bethelehem, and Matthew placed it in Nazareth, or if one gospel had Jesus die by crucifixion, and another had him die by stoning (as is recorded in the Jewish Talmud, b. Sanhedrin 43a). To my knowledge, nothing in the four New Testament gospels actually contradicts something in another gospel. There are differences, to be sure. But actual contradictions? I don't think so.

Most of the differences among the gospels are inconsequential matters of word choice or literary emphasis. But there are some differences that cannot be dismissed as trivial, no matter how we evaluate them. For example, in Matthew, Jesus faces three temptations from the devil: 1) turn stones into bread; 2) throw yourself off the temple, and; 3) worship me (Matt 4:1-11). Luke's narrative also includes three temptations, but in a different order: 1) stones to bread; 2) worship me, and 3) throw yourself off the temple (Luke 4:1-13). Of course many skeptical scholars would deny the historicity of this whole scene because it involves supernatural elements. But those who accept the possibility that this really happened face the peculiar variation in the order of temptations 2 and 3.

Is this a contradiction? I suppose it is if both Matthew and Luke were intending to present the three temptations in the order in which they actually occurred. In this case, either Matthew or Luke would be wrong, and it would be fair to refer to the variation between them as a genuine disagreement. But, if Matthew and/or Luke were seeking to present what really happened but in more of a thematic than a chronological order, then there would be no contradiction.

It does appear that the gospel writers did, at times, order events by theme rather than chronology. Consider another example. In Mark 6, well into Jesus's Galilean ministry in this gospel, there are two crucial events: Jesus's rejection in His hometown of Nazareth (6:1-6) and the arrest and murder of John the Baptist (6:17-29). Yet in the Gospel of Luke, the arrest of John is described in chapter 3, before Jesus begins His ministry (3:20), and the rejection of Jesus in Nazareth is placed at the very beginning of his ministry (4:16-30). If Luke was using Mark, as is likely, then he purposely moved these events for some reason or another. I think the move has to do with dramatic reasons primarily, but also theological emphasis. Luke, it seems, didn't think it was a problem to diverge from Mark's apparent chronology.

Seeing such chronological differences between the gospels, a naysayer might be quick to say, "Ah-hah! So there are contradictions. The gospels aren't reliable. They aren't historical." But, as I discussed in an earlier post, this would be another example of anachronistic judgment. It's taking our contemporary value of chronology and forcing it upon writers who did not share it. In fact, historians and biographers in the Hellenistic world often preferred thematic to chronological orderings of events. So the New Testament evangelists were simply doing what came naturally, and what would be expected by their readers. We do this sort of thing quite commonly today, though not in the writing of history or biography. Suppose, for example, I was going to tell you about my most recent summer vacation. I'd get the basic chronology in place: Big Sur, California for three days; driving north; Swan Lake, Montana for nine days; driving home via Utah. But as I narrated the events of Swan Lake, it's likely that I'd link common experiences rather than get them in the precise chronological order. I can't remember exactly which days we went tubing on the lake or jumping off the cliff or kayaking down the river. But I can organize my thoughts according to the types of activities we enjoyed. Listening to my narrative, you wouldn't accuse me of lying about my vacation, because you wouldn't expect me to pull out my journal and give you a precise day-by-day account of what happened. Similarly, the first readers of the gospels wouldn't have expected Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John to narrate all of the events in the precise order in which they happened. That's just not how it was done in those days. So if we come along and insist that, in order to be reliable, the gospels must get everything in precise chronological order, we're demanding something that is both anachronistic and inconsistent with the intentions of the evangelists. We're asking the gospels to be something that they're not. |

|

|

Here are two pictures from my summer vacation. In the photo above, my son is jumping off a cliff into Swan Lake, Montana. Below, my daughter and I are kayaking up the Swan River, where we see a moose. It really doesn't matter which event came first chronologically, does it? |

||

|

Ironically, this sort of demand has been placed on the gospels by unlikely bedfellows. Some very conservative Christians have argued that the gospel accounts must be 100% accurate in every last detail in order to be truly God's Word. Thus they fight for the absolute accuracy of every jot and tittle of chronology in gospels, believing that one tiny inconsistency brings down the whole authority of the Bible. On the flip side, many liberal scholars and others who want to undermine biblical authority also agree that the smallest inconsistency – read, "contradiction" – in the gospels invalidates their reliability. Thus, both the fundamentalist and the opponent of biblical authority end up making the same kind of mistake when it comes to evaluating the reliability of the gospels. (Note: what I've just said is not true of most leading evangelical scholars today. Many who affirm the inerrancy of Scripture also take seriously the intentions of the gospel writers and the literary conventions of their day.)

In this post I've focused on one particular kind of variation among the gospels (ordering of events) to illustrate both right and wrong ways to approach the question of differences between the gospels. In my next post I'll discuss other sorts of differences and lay out a way of seeing the gospels that values both their reliability and their individual distinctiveness.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Are There Contradictions in the Gospels? Section B ![]()

Part 13 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Wednesday, October 12, 2005

In yesterday's post I acknowledged that there are differences among the accounts of Jesus found in the New Testament gospels. One such difference was apparent chronology. Events in Matthew, for example, seemed to imply a chronological order that was not found in Luke. Yet to call this a contradiction would be to misconstrue the purposes of the evangelists who, like other Hellenistic biographers, were intending to present their material in thematic as well as chronological order.

There are other kinds of relatively common variations among the biblical gospels. These are neatly and comprehensively catalogued by Craig Blomberg in his book The Historical Reliability of the Gospels. Blomberg is a top-notch evangelical scholar who has written extensively on the gospels. If my blog series doesn't satisfy your desire for a more in-depth discussion of the reliability of the gospels, The Historical Reliability of the Gospels is well worth reading. I can't say I agree with everything in this book, but I can say that everything Blomberg writes deserves serious consideration.

In a chapter called "Contradictions among the Synoptics?" (the first three gospels are called "synoptic" because they are so similar), Blomberg discusses seven main types of supposed contradictions among the gospels:

1. Conflicting theology. This category has to do with genuine differences between the theological perspectives of the evangelists which are understood by some scholars to be in conflict with each other, rather than being complementary (which I would argue).

2. The practice of paraphrase. A verse in one gospel will be found in similar but not quite the same language in another gospel.

3. Chronological problems. I discussed this issue in my last post.

4. Omissions. Often one gospel doesn't include material found in another gospel. For example, Mark 11:12-24 tells the story of Jesus's cursing of the fig tree. This story is included in Matthew 21, but is not found in Luke.

5. Composite speeches. For example, some scholars believe that the Sermon on the Mount, in its present form, was created by Matthew out of individual sayings of Jesus, and not actually spoken by Jesus in the from in which it appears in Matthew.

6. Apparent doublets. These are stories in the gospels that could be two different versions of the same event, as in the case of the feeding of the 5,000 and 4,000 (Mark 6:32-44; 8:1-10 and parallels).

7. Variations in names and numbers. Examples would include the name(s) of the place where Jesus cast Legion out of a demonized man (Gerasa? Gadara? Matthew 8:28; Mark 5:1), or the healing of one blind man in Mark 10:46, where Matthew 20:30 seems to tell the same story with two blind men.

Let me discuss one example from the gospels that involves two of Blomberg's categories. It's from the story of the healing of the paralytic, where Jesus forgives the man's sins and so gets into trouble with some Jewish leaders (Matthew 9:2-8; Mark 2:1-12; Luke 5:17-26). The essential elements of this story are found in all three gospels -- the healing of the paralyzed man, the forgiveness of sins, the controversy with the leaders – as are many details. But one particular element of Mark's story is different in Matthew and Luke.

Mark's story begins with some people bringing a paralyzed man to Jesus so that He might heal him. But because of the crowds, they couldn't easily get to Jesus. So, according to Mark:

And when they could not bring him to Jesus because of the crowd, they removed the roof above him; and after having dug through it, they let down the mat on which the paralytic lay (Mark 2:4)

How does this curious detail play out in Matthew and Luke? Matthew omits the digging through the roof part altogether, a case of omitting material from another gospel. Luke includes the roof-breaking scene, but phrases it differently:

In Mark, the paralytic's friends "dug down" through the roof. In Luke they let their friend down "through the tiles." What explains this odd variation? Mark's version of the story reflects the fact that typical homes in Galilee in the time of Jesus had thatched roofs through which one could dig. But Luke, who is writing for a gentile audience, changes the imagery to that which would be intelligible to his readers, who would have been familiar with tiled rather than thatched roofs. It seems clear that Luke paraphrased Mark's text so that his readers wouldn't be confused about how one "digs through" a tiled roof. |

|

|

This is a photograph of the harbor in Rockport, Massachusetts, featuring the red fishing shack known as "Motif #1." It's one of the most commonly photographed and painted buildings in America. (This particular photo was taken by Stan McQueen.) Why am I showing this picture, you might wonder? I'll explain later. |

||

Though it's common in many scholarly circles to speak of "contradictions" as "the assured results of scholarship," in fact many if not all of the so-called "contradictions" have been carefully analyzed and interpreted by scholars who don't believe true contradictions exist. Many of the apparent contradictions turn out to depend upon superficial or rigid readings of the text. Yet efforts to harmonize the gospels are sometimes rejected as quaint remnants of an earlier day, rather than as legitimate efforts by historians to determine the true meaning of the gospel texts. To be sure, some proposed harmonizations are unpersuasive if not downright silly, but many deserve to be taken more seriously.

At the same time, some scholars – both conservative and liberal – have been reticent to take seriously the nature of the gospels as understood within their own time and culture. If it's true that the gospel writers were doing what biographers and historians were expected to do in the first-century Greco-Roman world, then we shouldn't be surprised to find plenty of variations between the gospels. So, to return to the example I'd noted previously, where Luke appears to change Mark's thatched roof to a tiled roof, some conservative scholars would no doubt try to solve this apparent inconsistency by claiming that the roof had both thatched and tiled portions, or that one could be said to "dig" through tiles, or something to ensure that both Mark and Luke are literally accurate. But these efforts are misguided, in my opinion. They force Luke into a modern mold that defines historical accuracy in a way different from Luke's own definition.

This does an injustice to Luke, and ultimately, in my view, to Scripture itself. It says, "I insist that the gosples be what I want them to be (or my culture wants them to be, or my theology wants them to be)," rather than "I receive the gospels as they are as part of God's Word, and will not require them to be something they are not." If God chose to work through biographers who, like their Hellenistic peers, paraphrased sayings or ordered events thematically rather than chronologically, who am I to say this is wrong? Isn't that asking, not only Luke, but even the Lord to conform to the values of my culture, rather than accepting God's choice to work within the constraints of another culture? Yes, indeed, there's a part of me that wishes God had waited to send His Son until He could have been captured on videotape. But I trust that the Lord chose just the right time to come in the flesh, even if this means I don't get the sort of accuracy in the presentation of the life of Christ that I'd prefer.

In my next post I want to pursue a bit further how we ought to think about the variations among the four biblical gospels, and suggest an analogy that helps me to make sense of this issue.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Are There Contradictions in the Gospels? Section C ![]()

Part 14 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Thursday, October 13, 2005

When we take seriously the nature of history and biography writing in the first-century A.D., and when we treat Matthew, Mark, and Luke as first-century biographies, and when we deal with their differences seriously rather than glibly, it makes little sense to speak of "contradictions" between the gospels. For all of their distinctiveness, the synoptic gospels tell more or less the same story of Jesus in more or less the same way.

The Distinctiveness of the Gospel of John

But the Gospel of John stands apart from the synoptics in many ways. True, the essential story of Jesus is found in this gospel as in the others (see my discussion in Part 11). And, true, the differences between John and the synoptics have often been overstated. But, after browsing through Matthew, Mark, and Luke, where, for the most part, Jesus utters short parables and pithy sayings, even the casual reader is struck by how different Jesus sounds in John. The short sayings have been replaced by much longer discourses. The primary message of the kingdom of God, though present in John, doesn't take the spotlight. Instead, in the fourth gospel Jesus speaks much more of Himself and His relationship with His Father. Here He is the bread of life and the light of the world. He is the good shepherd and the vine to which His disciples must stay connected. Plus, in John the apparent chronology and travelogue of Jesus's ministry is more complicated, with several trips between Galilee and Jerusalem. (Ironically, even many hyper-critical scholars regard John's timetable as fairly accurate.)

For some, the obvious differences between John and the synoptics clearly diminish the historical reliability of John. (A few have argued that John is older and more authentic, but they are small minority.) If Matthew, Mark, and Luke more or less get Jesus right, the argument goes, then John clearly gets Him wrong, from a historical point of view. The speeches of Jesus in the fourth gospel, it is claimed, reflect a long tradition of development within the community that ultimately produced this gospel. They have little to do with the real Jesus.

When I was in graduate school, this perspective reigned in the academic circles in which I danced. But even then there was a growing recognition that John, while distinctive, might actually preserve genuine, independent traditions about Jesus. Why, it was asked, must we assume that Jesus always spoke only in short quips? Didn't it make sense to believe that, in some settings, he spoke in longer discourses? And wasn't it possible that John, though a result of decades of tradition, actually preserved some of these discourses? Moreover, given that most critical scholars believed that John used older written sources (a "Signs Source" and maybe a "Discourse Source" and a "Passion Source"), the later date proposed for the fourth gospel (80s or 90s A.D.) didn't mean that its content was historically unreliable.

Not surprisingly, several conservative scholars have risen to defend the historical reliability of John. None has been more prolific in this regard than Craig Blomberg, the New Testament scholar from Denver Seminary whom I've mentioned earlier in this series. Blomberg wrote a book called, The Historical Reliability of John's Gospel: Issues & Commentary, in which he spends 346 pages defending the historicity of John's portrayal of Jesus. Blomberg is not a naïve harmonizer. And he takes seriously the distinctiveness of John's gospel. This distinctiveness accounts for the differences between John and the synoptics, and doesn't require denigrating the reliability of either.

How the Gospels Portray Jesus: An Analogy from New England

Of course for this approach to succeed, one needs to grant that the pictures of Jesus in the New Testament gospels aren't precise photographs so much as inspired paintings. If you've spent much time looking at paintings, you know that many are not "literal" in the photographic sense. Yet a great painting can capture a slice of reality that eludes the photographer. It can convey mood, feeling, and insight. And it can be profoundly "true" without being literalistic.

Consider the following example. In yesterday's post I included a photograph of the red fishing shack along the harbor of Rockport, Massachusetts, so called "Motif #1." I mentioned that this building is one of the most frequently painted and photographed of American landmarks. Here are four different paintings of Motif#1:

|

|

|

Artist: John Barbour |

Artist: Allison Goldstein |

|

|

|

|

Artist: Mary Poore |

Artist: Marilyn Swift |

Seeing these paintings, I wonder: Are they reliable witnesses to the reality of the red fishing shack? Yes, I would say so. A couple of the paintings are more literal, a couple more suggestive. None looks exactly like a photograph. (And, in fact, there are many, many distinct photographs of Motif #1.) Yet it would be wrong to criticize the painters because their art wasn't photographic, even as some criticize the gospel writers because they didn't get every jot and tittle exactly the same.

I you only saw one of these paintings of Motif #1, you'd have an idea what it "really" looked like. Chances are, if you were in Rockport and had never seen the red fishing shack, but had seen one of these paintings, you'd be able to recognize the shack, even though there would be some surprises waiting for you.

Similarly, if we only had one of the four gospels, we'd have a pretty good idea of what Jesus really did and said. Yet our perspective would be limited. The fact that we have four gospels enables us to see Jesus from a variety of points of view, and this enables us both to see different things in Jesus and to know with greater accuracy what Jesus was really like.

In tomorrow's post I want to reflect on how the differences among the gospels were dealt with in early Christianity, and how this helps us to evaluate the reliability of the gospels today.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Are There Contradictions in the Gospels? Section D ![]()

Part 15 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Friday, October 14, 2005

In an earlier post in this series I mentioned the attempt of a second-century Syrian Christian named Tatian to produce a single-volume harmony of the four gospels, one that was meant to replace the four as the primary narrative of Jesus's ministry. Though this harmony was popular in the lands of the eastern Mediterranean for a couple of centuries, eventually it was put aside in favor of the four original gospels. The early Christians, it seems, preferred four distinct narratives, with all their messiness, to one, neat and tidy harmonized one.

Sometimes people talk as if recognition of the differences between the gospels is a recent discovery. In fact, these differences have been recognized for as long as Christians have been reading four gospels, well back into the second century A.D. Sometime around 180 Ireneaus wrote a lengthy refutation of the Christian heresies in his day. In this piece, aptly called Against Heresies, Irenaeus not only refers to the four New Testament gospels as authoritative, but also attests to their distinctiveness. In a rather lengthy passage, he uses the four living creatures in Revelation 4:5-11 -- lion, ox, human, eagle -- as symbols for the gospels, noting how the symbols capture unique qualities of each gospel:

It is not possible that the Gospels can be either more or fewer in number than they are. . . . For the cherubim, too, were four-faced, and their faces were images of the dispensation of the Son of God. For, [as the Scripture] says, "The first living creature was like a lion," symbolizing His effectual working, His leadership, and royal power; the second [living creature] was like a calf, signifying [His] sacrificial and sacerdotal order; but "the third had, as it were, the face as of a man,"-an evident description of His advent as a human being; "the fourth was like a flying eagle," pointing out the gift of the Spirit hovering with His wings over the Church. And therefore the Gospels are in accord with these things, among which Christ Jesus is seated. For that according to John relates His original, effectual, and glorious generation from the Father, thus declaring, "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God." Also, "all things were made by Him, and without Him was nothing made." For this reason, too, is that Gospel full of all confidence, for such is His person. But that according to Luke, taking up [His] priestly character, commenced with Zacharias the priest offering sacrifice to God. For now was made ready the fatted calf, about to be immolated for the finding again of the younger son. Matthew, again, relates His generation as a man, saying, "The book of the generation of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham; " and also, "The birth of Jesus Christ was on this wise." This, then, is the Gospel of His humanity; for which reason it is, too, that [the character of] a humble and meek man is kept up through the whole Gospel. Mark, on the other hand, commences with [a reference to] the prophetical spirit coming down from on high to men, saying, "The beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, as it is written in Esaias the prophet,"-pointing to the winged aspect of the Gospel; and on this account he made a compendious and cursory narrative, for such is the prophetical character. (Against Heresies, 3.11.8)

In the end, Christian tradition followed Irenaeus's example of associating the gospels with the living creatures from Revelation, but not his particular associations. Matthew and Luke continued to be represented by the man/angel and the ox. But most Christians found the lion to be a better representation of Mark, and the eagle more fitting for John's soaring theology.

Nevertheless, my point is that Christians have recognized from the earliest times that the four biblical gospels are distinctive. Rather than disguising this fact with a single harmony, they celebrated the differences as part of God's plan for revelation. It's also worth noting that the second-century Christians didn't "clean up" the four gospels. It's true that some of the scribes did harmonize divergent texts, so there would be fewer differences among the gospels. But, by and large, the church kept the original texts intact, even though this meant preserving some of the very elements that could be labeled as "contradictions." This fact suggests two implications. First, it confirms the judgment that people in the Hellenistic world didn't expect historical or biographical works to get every word exactly right. Second-century believers could accept Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John as authoritative accounts of Jesus's life, even though there are acknowledged variations between them. |

|

|

"The Four Evangelists" by Spinello Aretino, a fresco on the ceiling of the sacristy of the church of San Miniato al Monte in Florence, Italy. You can see each evangelist with a representative "living being," an eagle, an angel, an ox/ram (with wings), and a lion (with wings). |

||

Second, the fact that the church did not prefer a single harmonized gospel, but instead kept the four distinct ones, suggests that the early Christians did indeed seek to preserve accurately the written accounts of Jesus's life, even with an awareness of the differences among these accounts. To put it differently, there was no conspiracy in the early church to clean up the gospels. The truth needed to be protected and preserved.

I'm aware that what I've just said flows upstream in some rivers of biblical scholarship. It's not uncommon to hear scholars argue that the gospels are primarily theological documents, and therefore are not meant to be historically accurate. Theology and history, it seems, are incompatible. In my next post in this series I want to tackle this issue. If it turns out that the motivations of the evangelists were more theological or pastoral than academic, if they were promoting a religious agenda more than writing history for antiquarian reasons, does this discount the reliability of the gospels?

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

If the Gospels are Theology, Can They Be History? Section A ![]()

Part 16 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Monday, October 17, 2005

If there's one thing all New Testament scholars agree upon, it's the fact that the gospels were not written merely for reasons of historical curiosity. The most liberal members of the Jesus Seminar and the most conservative scholars at Bob Jones University would surely agree that Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John weren't writing simply out of antiquarian interest. They weren't scholars who found Jesus fascinating and decided to write about his life. Rather, they were faithful believers in Jesus who sought to compose narratives of his ministry for pastoral or evangelistic reasons. In the language of our contentious world, the gospel writers had an agenda. They were writing theology, not raw history (as if there were such a thing).

The "Agenda" of Matthew and Mark

If the evangelists had an agenda, it certainly wasn't a hidden one. Each writer revealed his theological inclination quite plainly, as well as his personal faith in Jesus. Matthew begins his narrative by referring to Jesus as "the Messiah, the son of David, the son of Abraham" (1:1). Not exactly the confession of a neutral observer! Similarly, Mark starts his gospel in this way: "The beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, the Son of God" (1:1). So Mark's telling a story he believes to be "good news," and it concerns Jesus whom Mark believes to be the "Christ" (from the Greek christos, meaning "anointed one," messiah in Hebrew) and "the Son of God." (By the way, Mark speaks of the beginning of the "good news," which in Greek is euangelion, or "gospel." This is probably the origin of the use "gospel" as the genre for the four biblical biographies of Jesus. Mark himself probably didn't use "gospel" in this way, however, but as a summary of the content of his biographical narrative.)

The "Agenda" of Luke

Luke is even clearer about the purpose of his narrative. In an introduction reminiscent of secular historians who may have inspired Luke, he begins:

Since many have undertaken to set down an orderly account of the events that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed on to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and servants of the word, I too decided, after investigating everything carefully from the very first, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may know the truth concerning the things about which you have been instructed. (Luke 1:1-4)

Why is Luke writing an orderly account of the events concerning Jesus? Why did Luke pay close attention to a variety of sources, both oral and written? Why did he investigate everything carefully? Answer: so that Theophilus (a Christian unknown to us besides this passage and Acts 1:1) might "know the truth" about his faith in Christ. More literally, Luke is claiming to help Theophilus have "certainty" about the One in whom he believes. This is not academic history so much as intentional discipleship. It's teaching meant to help a believer grow in his faith.

The "Agenda" of John

The purpose of the fourth gospel is also plainly stated, though near the end of the book and not at its beginning:

Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not written in this book. But these are written so that you may come to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through believing you may have life in his name. (John 20:30-31)

According to this translation (NRSV), the primary purpose of John is evangelistic. He wrote "so that you may come to believe Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God." The Gospel of John may in fact be the first evangelistic tract in human history. (It is also, I expect, the most popular book in the Bible for evangelistic tracts today.) Ironically, John 20:31 is one of those rare verses in the New Testament where the actual Greek text isn't completely clear in one key place. If you were to look at the Greek behind the phrase "you may come to believe," you'd see something like this: pisteu[s]ete. The brackets were not in the original text, of course. They were added by the editors to indicate uncertainty about whether the original word was pisteuete or pisteusete. The first is in the present tense; the second in a past tense (aorist). Why does this matter? If John originally used pisteusete, then the translation "that you may come to believe" is correct, and the gospel is meant to lead non-believers to faith. But if he used pisteuete, then the translation should be "that you may continue believing," in which case the gospel is meant to encourage Christians to keep on in the faith. |

|

|

Agua Viva ("living water" in Spanish) is an evangelistic tract that features the text of the Gospel of John. |

||

Yet whether the fourth gospel was originally intended to convert or to encourage, there's no doubt that it was penned with a religious agenda. John wrote to foster belief in Jesus, thus joining the other evangelists as what we might call a theologian.

What I've said about the intentions of the gospel writers is confirmed by the gospels themselves. In the way they are structured, in the emphases of the stories, in the presentation of miracles, and in the stunning conclusion on Easter and thereafter, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John show their theological purposes. These are, without a doubt, theologically-motivated writings, composed for pastoral, evangelistic, or apologetic purposes, or some combination of the three. (I'm using "apologetic" here in the technical sense, meaning " to defend the faith" or at least "to equip Christians to defend the faith.")

So, if the evangelists were faithful believers in Jesus seeking to perpetuate or promulgate the faith, if they had various theological agendas, can we still regard them as historically reliable? At this point in the conversation many scholars say "No." Theology precludes history, or so we're told. I'll examine this position in more detail in my next post.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

If the Gospels are Theology, Can They Be History? Section B ![]()

Part 17 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Tuesday, October 18, 2005

When I took my first New Testament course in college, I was shocked by the extent to which my professor denied the historical reliability of the gospels. This was my first exposure to the sort of New Testament scholarship that later became all too familiar later on, and it was not a happy one. From everything he said in class, it seemed that my professor could hardly be a Christian.

Yet I knew he was an ordained minister, and one who sometimes did pastoral things, like preach or administer the sacraments. So when I found out that he was preaching in a nearby church, I was eager to attend. That's when I got the next shock from this professor. His sermon, though hardly evangelistic, articulated orthodox Christian truth. His prayers were astoundingly prayerful. He really seemed to talk to God, and mean it, even when he prayed in the name of "our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ."

Leaving that worship service I felt terribly confused. How could one who believed so little in the classroom believe so much in the sanctuary? How could he affirm so confidently that for which he saw so little historical basis? It was almost as if his faith was completely disconnected from history, and impervious to the skepticism of the academy, even if it was his own skepticism.

What I did not realize at the time was that my professor stood in a long line of theologians that stretched back to the 18th century. Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, a German best known for his plays, sought to defend Christian faith against skeptical historians who were chipping away at it. Lessing argued that theology can never be dependent upon history, because theology has to do with eternal truths, which can be known only by reason, while history produces only contingent knowledge. In his most famous phrase, Lessing argued that there is an "ugly ditch" that separates history and theology. Lessing profoundly influenced theology in the years to come, providing the intellectual foundation for my first New Testament professor's ability to separate history and theology. It enabled him to say, "As a Christian I believe in the virgin birth of Jesus, but as a historian I operate on the assumption that there are no children without natural fathers." Theology on one side, history on the other, and a wide, ugly ditch in between. Given that much of New Testament scholarship in the last century has been done by scholars under the influence of G.E. Lessing, we shouldn't be surprised that they tend to answer negatively the question I've been asking in this post: If the gospels are theology, can they be history? Theology and history are different things altogether, or so we're told. So if Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were writing theology, if they had religious agendas, then we shouldn't expect their work to be historically reliable. For these writers, it is argued, theology trumps history. Of course it's certainly possible for theology to be based on something other than events that can be studied by historians. The myths that underlie ancient Greek religion, for example, didn't really happen. But even in Scripture there are fictional stories that convey profound theological truths. Consider, for example, the parables of Jesus. There needn't have been a Good Samaritan for Jesus's theological point about love to be both truth and compelling. And we don't have to believe that there really was a Prodigal Son to rejoice in the picture of God's love that we find in the parable about that son. In both of these cases, and many more, theology is independent of history. |

|

|

G.E. Lessing, the German dramatist and theologian. No, there's no evidence that Die Coneheads were descendants of Lessing. |

||

|

Yet, the gospels present themselves as something other than expanded parables. They don't take on the look of what we might call historical fiction. Luke is clearest in this regard, by beginning his gospel with a prologue that intentionally echoes the prologues of other historians from his era. Moreover, for centuries almost all orthodox Christians have taken the biblical gospels as reliable narratives of what Jesus actually did and said, even though many of these Christians have seen far more than mere history in the gospel narratives. (For example, an allegorical approach to the gospels was popular for many centuries.)

The evangelists wrote reliable history because they cared about what happened in the past. And why did they care about the past? Because their theology was anchored in past events. After all, one cannot very well believe that salvation came through the atoning death of Jesus if that death didn't really happen. A nice story about a dying Messiah just wouldn't cut it. In the prologue to his gospel, John wrote: "And the Word became flesh and lived among us, and we have seen his glory, the glory as of a father's only son, full of grace and truth" (1:14). Undeniably, this is a theological affirmation. But it is theology that makes history matter profoundly. Believe that Jesus was really God in the flesh and you'll care deeply about what Jesus actually did and said.

Thus, if the gospel writers had a theology like that of G.E. Lessing, if they saw history and theology as distinct, then they wouldn't have cared a whit about history. But Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John didn't have the benefit of Lessing's wisdom. They, like the vast majority of Jews before them and Christians after them, believed that what happened made all the difference in the world. Therefore history wasn't inessential. It was at the heart of their theology.

In this regard the evangelists were quite similar to the Apostle Paul. In his first letter to the Christians in Corinth, Paul dealt with the view that resurrections, including the resurrection of Jesus, don't happen. Here's what he wrote:

If there is no resurrection of the dead, then Christ has not been raised; and if Christ has not been raised, then our proclamation has been in vain and your faith has been in vain. (1 Corinthians 15:13-14)

In other words, it's not nearly enough to regard the story of Jesus's resurrection as an inspiring fiction, or a symbolic rendering of some a-historical reality. What really happened to Jesus has everything to do with whether Christian faith is true or not. As with Paul, so with the gospel writers.

Sometimes I find it odd that certain scholars have so much trouble seeing how history and theology are intertwined, and how one with a theological "agenda" can, in fact, labor faithfully to pass on reliable history. This is hard for me to fathom because, frankly, I am motivated all the time by a theological passion that calls me to be a faithful historian. I'll explain more about this next time.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

If the Gospels are Theology, Can They Be History? Section C ![]()

Part 18 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Wednesday, October 19, 2005

In my last post I explained how some scholars disconnect theology from history, even asserting that one who writes theology cannot also be writing history at the same time. Since the writers of the biblical gospels were quite openly writing theology, this disqualifies them as reliable historians in the minds of some people. Yet, as I showed in my last post, the evangelists did in fact care a great deal about history, for theological reasons. They believed that God had acted decisively in Jesus of Nazareth, and therefore telling the truth of what he said and did was theologically important to them. Their theological "agenda," if you will, made them careful historians.

If you're wondering how a person who has a theological "agenda" can also be a trustworthy historian, I would offer myself as an example. Virtually every weekend I preach a sermon in the four worship services at Irvine Presbyterian Church. I freely admit that my sermons reflect a theological "agenda." I am seeking to help my congregants grow in their faith. And, at the same time, I'm also seeking to encourage non-Christian folk to put their faith in Christ. So I have a clear, open, and passionate theological agenda. No question about it.

This "agenda" leads me to tell stories, because I believe stories communicate powerfully in today's world. Most of my stories concern events that really happened, often in my own life or in the lives of people I know, though sometimes I use items that have appeared in the news or other sources. When I tell a true story, I make every effort to get the crucial facts right. This also comes from my "agenda," because I believe that my congregation will trust me if I am a reliable historian, so to speak. Moreover, my theology tells me that truth matters.

This means, for example, that when I get some wonderful story from the Internet, I work hard to verify its truthfulness before I use it in a sermon. Sometimes the most heart-rending stories turn out to be fictitious. A notable example is the tale of little Teddy Stallard (or Stoddard), the disadvantaged student who became a success because of the love of a teacher, Miss Thompson. This has been used in hundreds of sermons, often by pastors who talk as if they know Teddy personally. But, alas, Teddy is a fictional character, made up in a short story by Elizabeth Ballard. (For more on Teddy, see this blog post.)

Let me share an example of a story I have told in a sermon. This will illustrate how my theological "agenda" shapes the narrative and helps me to be an accurate historian.

A True Story with an "Agenda"

When I was a sophomore in college, I wanted to share my Christian faith with others. But, as an introverted person, I wasn't likely to walk up to a stranger or even a friend and get into a conversation about God. So I decided to pray and ask the Lord to help me.

One brisk Saturday evening in October, I decided to go down to Harvard Square and see if I could share my faith with somebody. The Square was filled with students from all over the Boston area, and it seemed a likely place for God to drop a seeker into my lap. I prayed earnestly for God to guide me to someone with whom I could talk openly about Christianity. "Lord," I prayed, "you know I'm pretty shy about this. So it would be great if you'd work a little miracle here, and find me somebody with whom I could share. And if you could make it obvious, that would be really helpful." With this prayer in my heart, I set off for the Square. I wandered around for a while, wondering where "my person" was. "Lord," I kept on praying, "please bring me somebody who wants to learn about You." Still nothing happened. After a half hour or so I began to feel both discouraged and silly. |

|

|

There are always lots of people in Harvard Square, sometimes with instruments. |

||

Just then, two young women approached me. "We're going to a party at Dunster House," they explained, "but we don't know how to get there. Could you help us?"

"Sure," I said. "Glad to." Meanwhile I thought to myself, "This is great. Not only has God brought these people into my life so I can talk to them about my faith, but they happen to be two attractive women. God you've outdone yourself this time!" Dunster House was about a ten minute's walk from Harvard Square, so I figured this would be plenty of time to engage these women in a conversation about God.

On the walk down to Dunster, I kept bringing up subjects that I felt sure would lead to a conversation about God. "I'm majoring in philosophy," I said, "Are you interested in philosophy?" They weren't. "Sometimes I wonder why we're here on this earth? Do you every think about this?" They didn't. Basically, they wanted to party at Dunster House, not reflect on the meaning of life with their tour guide. For ten minutes I tried everything I could think of to get the women to talk about God. Nothing doing. Of the thousands of students in Cambridge that night, they were the least interested in God.

When we got to Dunster House, I walked them to the door. They thanked me and left. I felt like a complete idiot. "Okay, God," I prayed, "I get the point. You've probably had a good chuckle over my silliness. Well, that's enough. I'm going home. This was a stupid idea." I left the entrance to Dunster House and headed back to my dorm. Just then I passed a student I recognized as being a friend of a friend. He said "Hi" so I returned the greeting as we went off in opposite directions. All of a sudden he stopped, turned around, and called to me, "Hey, are you Mark Roberts?" "Yes," I said, surprised that he knew my name. "Well, I'm Matt. I'm a friend of your roommate Bob." "Oh, yeah. Hello, Matt," I said. "I've been wanting to talk to you," Matt said. "Me?" I asked incredulously. "Why me?" |

|

|

The colorful spire of Dunster House along the Charles River. |

||

"Because I hear you're a Christian. I need to talk to you about God."

And so began a conversation that lasted well into the night. That conversation turned into a weekly Bible study, as Matt and I looked into the gospels to find out about Jesus. When we finished, Matt wasn't ready to give his life to Christ. But he was closer than he had been on that strange night when we met on the walk outside of Dunster House. End of story.

To the best of my 48-year-old memory, I have faithfully related the essence of this story: my desire to share my faith and my prayer for divine help; my meeting with the two women; our Dunster House destination; my "chance" meeting with Mike and his words to me. When I used this story in a sermon, my theological "agenda" motivated me to get the basic facts right. But it also helped me shape the telling of the story, choosing which facts were important and which were not. I did not, for example, saying anything about how the women I escorted were dressed or where they went to school, because these tidbits didn't contribute to the point of the story.

Now, I must confess, I did add a few "facts" that I'm not completely sure of. I said this happened "on a brisk Saturday evening in October." In truth, I don't remember if it was a Friday or a Saturday, and I'm not sure if it was in October or November. It was quite cool, this I remember, and I'm positive it was in the fall.

I also supplied a fair amount of dialogue in this story. Honestly, I don't remember the exact words with which I prayed, or the exact questions I asked the women as I escorted them to Dunster House. I've truly captured the basic sense of those conversations, but the words have long since escaped my memory. On the contrary, I might note, what Matt said to me is burned into my memory. I can still hear him say, "I need to talk to you about God." This was, as you can imagine, one of the most surprising and wonderful things I had ever heard. It was like a dream come true, as God answered my prayer so specifically and obviously.

Oh, I should add that "Matt" is not the name of the student I ran into outside of Dunster. I remember his real name, but when I tell stories like this, I often change names to protect the confidentiality of the person(s) involved. In this particular case I could have safely used "Matt's" real name, but often I need to be careful.

In conclusion, did my "agenda" lead me to tell this story in a sermon? Yes. Did my "agenda" help me to choose what to include and what to exclude from this story? Yes. Did my agenda preclude me from being a good historian? Decidedly not. I'm quite certain that this event happened, and in more or less the way I've narrated it (with the exceptions I've mentioned above). In fact, my "agenda" as a preacher motivated me to tell this story, to tell it in a certain way, and to make sure that the essential elements were absolutely truthful. My theology led me to be a trustworthy historian.

So, though I have exercised certain freedoms in telling this story, the essence is exactly the way I remember it. And my accuracy in relaying this story stems from my theological convictions and motives. If you discovered that, in fact, this was a nice little piece of religious fiction, then the power of the story would vanish. After all, what makes it so compelling is the fact that, after I had prayed to share my faith with someone, a virtual stranger said to me, "I need to talk with you about God." This is either a fabrication, an incredible coincidence, or a miracle of God. I vote for miracle.

Speaking of a miracle, here is one of the major problems when it comes to the reliability of the gospels. How can we believe that narratives so full of the supernatural are historically accurate? To this question I'll turn in my next post.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Do the Miracle Stories Undermine the Reliability of the Gospels?

Section A ![]()

Part 19 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Thursday, October 20, 2005

I'm a natural-born skeptic. I admit it. For example, if I hear someone claim that a miracle has happened, my first impulse isn't to rejoice, but to doubt. It's not that I don't believe miracles occur. In fact I do. But I'm all too aware of how people can exaggerate, or be carried away by emotion, or even fall prey to deception. People today are so eager for some sign of supernatural power, whether divine, angelic, or paranormal, that they'll often see miracles where folks like me would see coincidence, malfeasance, or merely good luck.

My skepticism about the miraculous was nourished by my senior thesis in college. A philosophy major, I chose to write on the famous – some would say infamous – argument against miracles put forth by the 18th century philosopher David Hume. My thesis, The Miraculous Philosophy of David Hume, was not a refutation of Hume's argument. Rather, I attempted to dissect this classic case against miracles by carefully exegeting section 10 of Hume's Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, viewing this argument in light of the cultural and philosophical milieu in which Hume wrote. His basic point was that the case for miracles is intrinsically weak, given the very nature of the miraculous. If you tell me, for example, that you became invisible at work today, I will not believe you because I have no experience of people becoming invisible, but I do have experience of people deceiving themselves or trying to deceive me. Thus, as a good Humean, I would find it more likely that somebody is deceiving somebody than that you actually became invisible.

Yet, in spite of my innate and well-nourished skepticism, I do not believe that the presence of miracles stories in the gospels makes them unreliable, though it does complicate the evaluation of their reliability. If there were no miracles in the New Testament gospels, then many scholars today as well as many ordinary folk would be much more likely to acknowledge the gospels' historical reliability. Of course, if there were no miracles in the New Testament gospels, if Jesus didn't heal the sick, cast out demons, and eventually rise from the dead, there would be no New Testament gospels. In fact, there would be no New Testament at all. Jesus would have been dismissed by His contemporaries as an overly optimistic but deceived prophet who proclaimed the kingdom of God but didn't deliver on His promises. His death by crucifixion would have been the end of things. Jesus would have quickly been forgotten as one more wannabe Messiah who failed at the job. Scholarly efforts to take away the miraculous from the gospels inevitably fail to be persuasive because, like it or not, the narratives of Jesus's ministry are chock full of supernatural events. His message and miracles go hand in hand.

There's no way I can begin, in this blog post, or even in this series, to address the myriad of philosophical and historical issues connected with the miracles of Jesus. If you're interested in a more extensive conversation, I'd recommend the following resources:

Craig Blomberg, The Historical Reliability of the Gospels, chapter 3.

R. Douglas Geivett and Gary R. Habermas, editors, In Defense of Miracles: A Comprehensive Case for God's Actions in History.

Graham H. Twelftree, Jesus the Miracle Worker: A Historical & Theological Study.

Maybe at some point in the future I'll do a whole blog series on the issues surrounding the miracles of Jesus. For now, however, I'll offer some general theses on why the presence of miracles in the gospels do not keep me from affirming their reliability.

Some Theses on Miracles and the Reliability of the Gospels

1. I am a theist who accepts the theoretical possibility of miracles, and therefore I am open to the possibility that the miracles in the gospels actually occurred. My theistic worldview is crucial in my estimation of the gospels. I believe that there is a Supreme Being, One who created all things, and can, if He wishes, do things within His creation that are extraordinary. Thus I believe miracles can happen. I you are not a theist, and you don't believe in the possibility of miracles, then you'll most likely reject the reliability of the gospels. A few scholars have tried to "naturalize" the miracles of Jesus, explaining healings as a matter of psychosomatic suggestion, for example, but this approach hasn't been persuasive, either to most scholars or to most lay people. |

|

|

Though not a miracle, the turning of leaves in the fall is truly one of life's wonders. This scene is from Nevada, near Lake Tahoe. |

||

2. Miracles do not contradict science.

Of course it's common for people to claim the opposite, and to argue that miracles can't occur because they are contrary to science. But, in fact, they aren't contrary to science so much as outside of the realm of science. Science studies natural events. Miracles, by definition, are not natural, but extra-natural, or outside of nature. Thus science has nothing to say about them. Now it's true, of course, that many scientists have naturalisitic worldviews, in which no supernatural being exists. So, naturally, they deny the possibility of miracles, but this not something they can defend scientifically. It's a philosophical position, not a scientific one. There are also many scientists who are theists and who, therefore, allow that miracles might occur.

3. A worldview that includes supernatural powers makes the best sense of some of life's mysteries.

Now I'm fully aware that, throughout history, people have credited or blamed the gods for unexplained natural events. And I'm also willing to concede that there may be many more natural powers than we currently understand or acknowledge. But certain kinds of phenomena seem to be best explained in light of the existence of supernatural beings, both good and evil. I'm thinking here, not only of well-established divine miracles, which are plentiful throughout the world today, but also of demonic realities such as pictured in the recent film, The Exorcism of Emily Rose. (For an expanded discussion of the reality of demons, see my series Do Demons Exist? . This series was originally part of a larger conversation on OneTrueGodBlog, which I highly recommend.) I, myself, have experienced things in life that have convinced me of God's miraculous involvement in human life. The story in my last post about Matt is one example among many. Many things in my life and ministry have been so exceptional, so coincidental, and so wonderful that I cannot account for them apart from belief in a benevolent, miracle-working God.

Tomorrow I'll continue this discussion of miracles and the gospels.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |

Do the Miracle Stories Undermine the Reliability of the Gospels?

Section B ![]()

Part 20 of series: Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Posted for Friday, October 21, 2005

Yesterday I began a conversation about the miracles in the New Testament gospels. Acknowledging that they muddy the waters when we're seeking clarity about the gospels' reliability, I nevertheless I began presenting a number of theses on why the miracle stories in the gospels do not undermine the gospels' reliability. Today I'll add three more theses and wrap up this discussion of miracles and the gospels. I admit that this conversation is very minimal. If you're looking for a more complete treatment of miracles in the gospels, check out the bibliographic resources I recommended in yesterday's post.

Three More Theses on Miracles and the Reliability of the Gospels

4. The "parallels" to the miracles of Jesus found outside of the Bible do not undermine the authenticity of the New Testament accounts, and in many cases they actually support an argument in favor of the reliability of the gospel stories.

It's common for scholars and others to argue that the existence of miracle stories in the literature of the Hellenistic world somehow invalidates the historical reliability of the gospels. People in the Greco-Roman world told fantastic stories, not only about gods like Hercules, but also about famous humans, like Apollonius of Tyana, a first-century, wonder-working philosopher. We're told that the early Christians, aware of these tales, sought to make Jesus competitive in the marketplace of Hellenistic superheroes, and therefore invented stories demonstrating His supernatural prowess.

On the surface, this account of the miracles of Jesus seems solid. But a peek beneath the surface shows it to be full of holes. For one thing, most of the stories of miracles in pagan religions were far more fantastic and removed from everyday experience (like the labors of Hercules, for example). The miracles of Jesus, on the contrary, dealt with relatively ordinary circumstances, like sickness or hunger. Moreover, the pagan miracles were often described in an exaggerated, entertaining style. The miracles of Jesus, by contrast, seem almost understated. Furthermore, the gospels record situations in which Jesus actually lacks supernatural knowledge (Mark 5:30) or power (Mark 6:1-6). In other instances His efforts at exorcism (Mark 5:1-8) and healing (Mark 8:22-26) don't at first succeed. One would think that if the early Christians were making up stories about Jesus, they could have done a much better job, both in content and in form. And surely the gospel writers, if they were so concerned to polish Jesus's image as the superlative wonder worker, would have cleaned up the stories that seemed to tarnish it.

The whole "pagan influence" theory of the gospel miracles forgets that the earliest Christians were not gentiles competing with Apollonius of Tyana, but Jews who believed that Jesus was Israel's Messiah. Many if not all of the oral traditions about Jesus's miracles emerged from this early, predominantly Jewish milieu. If the stories of Jesus's miracles had in fact been fabricated by the first Christians, it's unlikely they would have used pagan models. Old Testament exemplars, like the miracles of Moses or Elijah, would have served the purposes of the first Christians much better.

Now there are some fantastic and fictitious miracle stories about Jesus. And it's quite possible that these were invented to help Jesus compete successfully with the other philosophers and gods of the Hellenistic world. But these stories appear, not in the biblical gospels, but in the non-canonical imitations. In the so-called Infancy Gospel of Thomas, for example, Jesus magically lengthens a board that his father cut too short, and raises a playmate from the dead after he died from an accidental fall. The more you read the miracle accounts in the post-biblical gospels, the more you'll be impressed by the reserved and understated character of the New Testament stories.

Or course if you don't believe miracles are possible, then you won't be inclined to accept the New Testament accounts as reliable, but you'll have to admit that they're much less obviously fantastic, in form and style if not in substance, than their non-canonical counterparts.

5. When it comes to reasons for accepting the gospel miracles as historically accurate, the resurrection leads the way, however ironically.

An argument for the historicity of the gospel miracles rests on several factors, including, put not limited to: the overall character of the gospels, the modesty of the miracle stories, the surprising "lapse" in Jesus's powers at some points, and the simple fact that the miracles of Jesus account for His widespread popularity. But it wouldn't make sense to argue concerning any one of Jesus's miracles, that, apart from its existence, early Christianity doesn't make historical sense.

Except for the resurrection. Take away the resurrection of Jesus, and you'll have a devil of a time making sense of the origins of Christianity. Jesus died a most shameful death, to all appearances ending His brief stint as a messianic pretender. Nobody in His time, other than Jesus Himself, had any place for a suffering, dying Messiah. After Jesus's demise, His disciples were a devastated, frightened bunch who had lost all hope. But then, only a short time thereafter, they became a fearless band of evangelists who ended up changing the course of history. Their message, strangely enough, was that the crucified Jesus had indeed been Israel's Messiah, and that through Him God was inaugurating His kingdom. All of this was predicated on a singular conviction: that Jesus had been raised from the dead, and that He was alive, not as a resuscitated corpse, and not as a symbol of spiritual rebirth, but as the living Lord.

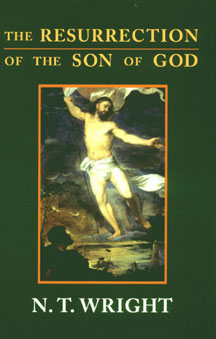

What explains the counter-intuitive rise of early Christianity? The resurrection, plain and simple. Of course it's not nearly so simple for scholars who either disbelieve in the possibility of resurrection or who believe that scholars just can't figure something like the resurrection into their historical explanations, even if they accept such things in their personal faith. But, in my opinion, all efforts to explain why the defeated disciples became enthusiastic evangelists fall short apart from the resurrection. The simplest, most elegant, and most compelling account of the origin of Christianity rests upon this unprecedented miracle. (For an extraordinarily persuasive (and lengthy) exposition of this point, see N.T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God.) Why would a natural-born skeptic like me believe that Jesus actually rose from the dead? Because this offers the best account of the birth of Christianity. Of course the fact that I'm a theist undergirds my willingness to accept what otherwise I would deny as impossible. Yet it certainly helps that non-miraculous and non-theistic theories of Christian origins are so unpersuasive. Once I've allowed that the gospels faithfully narrate the resurrection of Jesus, which is one of the most astounding miracles of all, then I've opened the door to accepting the historicity of the other miracles as well. If Jesus actually rose from the dead, it's not hard to imagine that he actually healed the sick, cast out demons, or even walked on water. |

|

|

What I have argued superficially and awkwardly in a few paragraphs Wright covers in 800 packed, brilliantly-argued pages. |

||

I said above that resurrection leads the way to the acceptance of miracles in the gospels, however ironically. What I meant was that, of all the miracles in Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, the resurrection is perhaps the most difficult for many people to accept. Naturalistic scholars have found ways to account for Jesus's healings (psychosomatic or paranormal) and exorcisms (the power of suggestion). But the resurrection cannot be so stripped of its supernatural essence. The once popular view that Jesus didn't really die on the cross, but just "swooned," only to "rise" by awaking in the refreshing coolness of the tomb, has long since been discarded as utterly incredible. So the resurrection leads the way to acceptance of miracles, even though it is one of the hardest of all miracles to accept. Nevertheless, once you believe that Jesus in fact rose from the dead, it makes it easier to believe that the gospel stories about His other miracles have a solid basis in fact, not early Christian fiction.

6. It is reasonable to believe that the gospel miracles actually happened, but this cannot be proved beyond a shadow of a doubt.

I've tried to show that it's reasonable to believe that the miracles of Jesus as portrayed in the canonical gospels actually happened. The theory that Jesus performed miracles surely helps to account for His widespread influence in His own day. And the theory that He rose from the dead helps to explain the otherwise inexplicable rise of early Christianity. Such theories are reasonable, as I've explained, from the perspective of a theist who believes in a God who can do unusual things in His creation.

Reasonableness and proof are not the same thing, however. There is no way I can prove that Jesus actually did miracles or actually rose from the dead. Neither can anyone prove that He didn't, for that matter. History doesn't allow for such proof, but only contingent knowledge based upon evidence, probabilities, and reasoned argument. So, as a historian of early Christianity, I would argue that it's highly probable that the gospels faithfully portray the miracles of Jesus as they happened, given, of course, the shaping of tradition and the evangelist's intentions. I would also argue that a theistic approach which allows for miracles produces the most elegant and persuasive account of Jesus's ministry. Yet historical inquiry can take us only this far along the road of reasonableness. The next steps belong to the realm of faith.

| Home. Do you have a comment about this post? Either e-mail me or visit my guestbook. Thanks. |