|

hristmas Carols; Christmas Carols History; Christmas Carol Stories; Silent Night - History; Hark the Herald Angels Sing - History; Joy to the World - History

Christmas Carol Surprises

by Rev. Dr. Mark D. Roberts

Copyright © 2004, 2007 by Mark D. Roberts

Note: You may download this resource at no cost, for personal use or for use in a Christian ministry, as long as you are not publishing it for sale. All I ask is that you give credit where credit is due. For all other uses, please contact me at mark@markdroberts.com. Thank you

Some Bits of History

Part 1 in the series “Christmas Carol Surprises”

Posted at 11:00 p.m. on Sunday, December 19, 2004

Okay, I admit it. I love Christmas carols. I love the way they sound. I love the memories they evoke. And, in many cases, I love the truths they celebrate. So in the next few days I’m going to do a short series on Christmas carols. I promise that it will be informative, fun, and maybe a bit inspirational too.

Christmas Carol Fun

Do you like Christmas carols? Do you think you know Christmas carols pretty well? Then I have a website for you. FunTrivia.com, which claims to be the “world’s largest, best, and most fun trivia website” has a great collection of Christmas music trivia quizzes. My favorite is “Christmas Carol Trivia: Sacred Carols,” but there are many more. Warning: You can spend a lot of time at this site if you’re not careful.

Ancient Christian Songs

Early in the second century A.D. the Roman governor of Pontus and Bithynia (northern Turkey) wrote letters to the Emperor Trajan. In one of these letters he describes the actions of some troublesome (from Pliny’s point of view) Christians: “They asserted, however, that the sum and substance of their fault or error had been that they were accustomed to meet on a fixed day before dawn and sing responsively a hymn to Christ as to a god, . . .” This is one of the earliest references to Christian singing.

Many scholars believe that early Christian songs are quoted in the New Testament letters of Paul. One of these, in Philippians 2:5-11, includes the following lyrics:

[Christ Jesus] who, though he was in the form of God,

did not regard equality with God

as something to be exploited,

but emptied himself,

taking the form of a slave,

being born in human likeness.

And being found in human form,

he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death—

even death on a cross. (2:5-8)

Though we wouldn’t call this a Christmas carol, it does focus on the birth of Jesus and this his death. It sees this birth through the lens of theology rather than narrative, however. Some scholars see this song as a theological statement informed by the early stories of Jesus’s birth. This is possible, but cannot be proven.

Carols as Forbidden Folk Music

Although the church did include religious singing in its liturgy surrounding the birth of Jesus, carols were written in a more popular idiom. The word “carol” originally described a song that had verses and a repeating chorus. It was frequently sung in the context of folk dancing (circle dancing). Most of the Christmas carols in the Middle Ages were secular or pagan in origin, and thus they were not popular with religious officials. On more than one occasion, as early as the 7th century and as late as the 16th century, Roman Catholic councils attempted to ban Christmas carols altogether. Only the reverent sounds of sacred chant were deemed appropriate for memorializing the birth of Jesus.

My own theological ancestors, the Reformed Puritans of Britain, attempted to get rid, not only of Christmas carols, but also of Christmas itself. They attempted to “purify” the church of both secular and Roman Catholic elements. When they were in power in Britain in the middle of the 17th century, the Puritans actually succeeded in making the celebration of Christmas illegal. No carols, no fun, no Christmas! The earliest Europeans in America, coming from English Puritan stock, did not celebrate Christmas, and in fact made a point of not doing so. In fairness to these folk, however, we should understand that the secular and pagan celebrations of Christmas were often filled with drunken excess, rather more like Mardi Gras in New Orleans than most secular Christmas celebrations today (except, perhaps, for office parties run amuck).

The Influence of St. Francis

Many historians credit St. Francis of Assisi with vitalizing the Christian celebration of the birth of Christ. Early in the 13th century he created the first (or one of the first and surely the most famous) life-sized Nativity scenes, complete with live animals, a real baby in the manger, and a worship service. This service included the singing of lively, joyful Christmas music – something that was virtually unknown up to this time. Francis forged the combination of genuine love for Christ with genuine celebration, which almost always includes joyful music.

The Revival of Christmas and Christmas Carols

Even though the celebration of Christmas was technically legal from the late 17th century and onward, the holiday was largely ignored by the English. Continental Europeans were more apt to celebrate Christmas with a combination of secular, pagan, and Christian traditions. It’s from the Continent that we get, for example, the traditions of Christmas trees and Santa Claus. In 19th-century England, however, Christmas was largely forgotten, a victim of religious disinterest and industrial urbanization.

Yet in the Victorian Age new champions of Christmas emerged, among them Clement Moore (who wrote the poem we know as “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas” in 1822) and Charles Dickens (who wrote several Christmas stories including, of course, “A Christmas Carol” in 1843”). Under the influence of these and other writers, Christmas became a popular celebration, a day for feasting and family. During this same period of time many of our favorite carols were either written or published for the first time. |

|

| |

This painting by Giotto (c. 1300) depicts the "crib" of St. Francis. Notice the singers in the back row.

|

|

| |

The singers in the back row are easier to see in this detail. Notice the vigor of their singing! They're singing joyous carols, indeed.

|

Resources

For more information about Christmas carols, see The New Oxford Book of Carols. A fantastic online source of information is The Hymns and Carols of Christmas. Much of what I have summarized in this post comes from these two sources.

Home

Favorite Christmas Carols

Part 2 in the series “Christmas Carol Surprises”

Posted at 11:00 p.m. on Monday, December 20, 2004

What are your favorite Christmas carols?

From one perspective this is an easy question. My guess is you already have some answers in mind: “Joy to the World,” “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” “White Christmas,” “Jingle Bells,” and, perhaps the all time favorite, “Silent Night.” Yet from another perspective this question isn’t quite so simple. When I refer to carols, do I mean sacred carols vs. holiday songs? Or am I lumping them all together? And what about songs that seem to bridge between the sacred and the popular, like “Little Drummer Boy” or “Do You Hear What I Hear?”

| The debate about what constitutes a Christmas carol (vs. holiday song, or Christmas hymn, or seasonal folk song, or . . .) is a complicated one. Musicologists used to describe a carol as a song with verses and a repeating chorus, usually used in dancing. Indeed, the word “carol” comes from the Old French word “carole,” that refers to a circle dance. In centuries past there were carols not only for Christmas, but for other holidays as well. In those times church leaders distinguished between sacred Christmas music (hymns, chants) and secular carols, which the leaders often denigrated or even tried to outlaw altogether. But in recent times the word “carol” has become inescapably associated with the Christmas music. |

|

| |

A folk dancing group doing a circle dance. |

As I think about Christmas music, I make a rough and ready distinction between religious Christmas carols and secular carols or holiday songs. “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen” is a religious carol, while “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” is a holiday song. This distinction wouldn’t stand up to close scholarly scrutiny, especially given the crossover songs, but it works fairly well in practice. It's more about the content of the lyrics than the genre of the music.

So, then, let me ask two questions: First, what are your favorite religious Christmas carols? Second, what are your favorite holiday songs? Note: Tomorrow I'll work on the second question. Today I'll focus on the first.

Favorite Religious Carols

I’ve looked in vain for some definitive survey that would tell us which religious carols Americans like most? If you find one, please let me know. It would be especially interesting to see how preferences vary with age, religious commitment, ethnicity, and other variables. But since I haven’t found anything systematic, you're stuck with my own rather idiosyncratic observations.

It seems to me that sacred Christmas music can be organized in a four-tier hierarchy. The top tier contains songs that are sacred classics, songs that will be sung in most churches and will even be heard in secular malls and concerts during the holiday season. One characteristic of a top tier song is that Christmas just wouldn’t be Christmas unless you heard this song several times. Second tier carols are favorites, but they haven’t quite made it into the top tier. They’ll be sung just a little less frequently than the others, and are loved by somewhat fewer people, but not less passionately. Third tier carols will be heard and sung, but much less frequently. The fourth tier contains carols that are rarely sung today, even though they may be personal favorites for some individuals. I suppose I could add a fifth tier: Most Hated Carols. But somehow that wouldn’t be in keeping with the holiday spirit.

So here’s my shot at the hierarchy. Remember, this reflects my experience as an Anglo, American, Protestant. Now I’m sure almost every reader will want to move things around, to add or to subtract. If you want to have some fun, make your own hierarchy. This could even be a delightful Christmas afternoon game to be shared among friends and family after the presents are open. I do reserve the right to change my order, especially as I hear from you.

| Mark's Ranking of Religious Christmas Carols |

| Tier 1: Greatly loved and always sung |

“Silent Night,” “O Come All Ye Faithful,” “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing,” “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” “Away in a Manger” “Joy to the World” |

Tier 2:

Loved by most and usually sung |

“The First Noel,” “Angels We Have Heard on High,” “It Came Upon the Midnight Clear,” “O Holy Night,” “Good Christian Men Rejoice,” “God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen,” “We Three Kings of Orient Are,” “What Child is This?” “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” “The Twelve Days of Christmas,” and possibly “Mary, Did You Know?” (It will remain to be seen whether "Mary, Did You Know?" lasts in its current popularity.) |

Tier 3:

Loved by some and sometimes sung. |

Too many on this level to mention more than a few: “Good King Wenceslas,” “In the Bleak Midwinter,” “The Holly and the Ivy,” “I Saw Three Ships,” “I Wonder as I Wander” "Once in Royal David's City" |

Tier 4:

Loved by a few and rarely sung |

Fourth Tier: Loved by few and rarely sung. Far too many to make a list, but I’ll share a few of mine. These are Christmas songs I dearly love, though they’re rarely heard or sung. “Lo, How a Rose E’re Blooming”, “In the Bleak Midwinter,” “What Sweeter Music.” |

"What Sweeter Music" was set to music by the English musician and conductor John Rutter in 1987. The lyrics are from a Christmas poem by the seventeenth-century English poet Robert Herrick. (Herrick is perhaps most famous for the line: “Gather ye rosebuds while ye may.”) I’ll print the lyrics to Herrick’s poem below, in case you’re interested. But without the music, the words just don’t sing. Unfortunately I can’t put up a recording of Rutter’s song (copyright limitations), but this link will take you to a link where you can hear part of the song (and buy the album, if you wish).

A Christmas Carol, Sung to the King in the Presence at White-Hall

[CHORUS] What sweeter music can we bring,

Than a carol, for to sing

The birth of this our heavenly King?

Awake the voice! Awake the string!

Heart, ear, and eye, and everything.

Awake! the while the active finger

Runs division with the singer.

[VOICE 1] Dark and dull night, fly hence away,

And give the honor to this day,

That sees December turned to May.

[2] If we may ask the reason, say

The why, and wherefore, all things here

Seem like the springtime of the year?

[3] Why does the chilling Winter's morn

Smile, like a field beset with corn?

Or smell, like to a mead new-shorn,

Thus, on the sudden?

[4] Come and see

The cause, why things thus fragrant be:

'Tis He is born, whose quickening birth

Gives life and luster, public mirth,

To heaven, and the under-earth.

[CHORUS] We see Him come, and know Him ours,

Who, with His sunshine, and His showers,

Turns all the patient ground to flowers.

[1] The darling of the world is come,

And fit it is, we find a room

To welcome Him.

[2] The nobler part

Of all the house here, is the heart,

[CHORUS] Which we will give Him; and bequeath

This holly, and this ivy wreath,

To do Him honor; who's our King,

And Lord of all this reveling.

Home

Favorite Holiday Songs

Part 3 in the series “Christmas Carol Surprises”

Posted at 11:00 p.m. on Tuesday, December 21, 2004

I can still remember the moment many years ago when my youth leader at church said, “You know, “Jingle Bells” really isn’t a Christmas carol. It’s more of a winter song.” I was stunned. This had never occurred to me before. I quickly went through the lyrics of “Jingle Bells” in my head, only to realize for the first time that this beloved song really said nothing about Christmas at all. It mentioned neither the secular nor the spiritual aspects of the holiday. For the first time in life, I received a “Christmas carol surprise.” A song I knew and loved turned out to be something different from what I had assumed it to be.

I’ve since learned that “Jingle Bells” has a few more surprises to offer. It was written in the mid-1800’s by a church organist, James Pierpoint. It was first performed, not in a Christmas service, but in a Thanksgiving program at Pierpoint’s church. There’s actually quite a hot debate over where Pierpoint actualy wrote “Jingle Bells.” People from the city in Georgia where the song was first performed claim he wrote it there. But folk from Medford, Massachusetts, where Pierpoint lived before moving south, claim he wrote his famous jingle in a town tavern.

In my last post I mentioned my rough and ready distinction between religious Christmas carols and secular carols or holiday songs like "Jingle Bells." Of course many holiday songs mention Christmas, but almost never as a religious holiday. I’m not complaining about this, by the way, just mentioning it. I happen to think that many of the secular Christmas traditions are wonderful (putting up Christmas lights, eating festive food, getting together with friends and family, etc.). Songs that commemorate these traditions can also be delightful, even if they’re not spiritually edifying. (Here I part company with my Reformed and Puritan theological ancestors, who disliked Christmas carols in general, and despised the secular songs as contradictory to the solemnity of the birth of Christ.)

If you’ll grant my distinction between religious carols and holiday songs, then let me ask you: What are your favority holiday songs? Which holiday songs do you love the most? (I addressed religious carols in my last post.)

Before I answer this question for myself, I want to make a prediction about your answer: You will choose several songs written in America between 1932 and 1952. In fact, it wouldn’t surprise me if most or all of your choices fall into this category. Now I’m not psychic or anything like that. But I do know that the majority of our most popular holiday songs today were written in that time frame, including “White Christmas” (1942), “The Christmas Song” (“Chestnuts roasting”, 1946), and “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” (1949). |

|

| |

One of my favorite family traditions is an annual walk around Balboa Island (Newport Beach) to see the decorated homes and boats. Here are my wife and son on our recent adventure.

|

It strikes me as notable that so few of our favorite holiday songs were written in the last forty years. So far I’ve been able to identify only these: “We Need a Little Christmas” (Jerry Herman, 1966), “This Christmas” (Donny Hathaway and Nadine McKinnor, 1968), “Feliz Navidad” (José Feliciano, 1970), “Happy Christmas” (John Lennon, 1971),” “Wonderful Christmastime” (Paul McCartney, 1979). If you have any other suggestions, please let me know. Obviously it takes time for songs to become popular, not to mention old favorites. But I don’t see many recent songs on this trajectory. Why not, I wonder?

One could argue that many of the songs from the 1930s-1950s era were promoted through movies, and that would certainly be true. Just take Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas,” for example, which was featured in the 1942-film Holiday Inn. But there are lots of movies today with Christmas themes. Do they feature new holiday songs on their way to becoming classics? I don’t think so. In fact most of these movies tend to feature the older songs, though they may be re-recorded by younger singers. Take last year's Christmas hit Elf. It's songs are almost all from the 1930s-1950s. (Here's a strange bit of trivia. The soundtrack for Elf was composed by John Debney, who also composed the soundtrack for The Passion of the Christ. Now there's some diversity!)

What explains the tendency of today's films to use older music? I’m sure nostalgia has something to do with it. When we hear Nat King Cole’s rendition of “The Christmas Song” we not only enjoy this song as a piece of music but also it generates fond memories of times gone by, at least for many of us. But I don’t think nostalgia solves completely the riddle of no new music. I’m inclined to believe that it’s also about the change in America since the early 60’s. Vietnam, Watergate, the sexual revolution, and so forth had an impact on the soul of America. We lost our romanticism, for better or for worse. We became more realistic, more cynical, more unwilling simply to enjoy smelling “chestnuts roasting on an open fire.” Most of the holiday music from decades past is very romantic. It’s all about happiness, beauty, love, and Christmas magic. Winter isn’t a time when homeless people struggle to find shelter or lonely people fall into deep depression. Rather, the older music celebrates “Jack Frost nipping at your nose” as you walk through a “winter wonderland,” enjoying a “white Christmas” while crying out “Let it snow! Let it snow! Let it snow!”

Okay, enough philosophizing. Now let’s get down to business. What are the most beloved holiday songs? We can actually get an objective answer to this question, because ASCAP publishes the “Top 25 Holiday Song List” every year. They came out with the 2004 version three weeks ago. This list tells us which of ASCAP’s songs have been performed most often. I’ll print the list, along with the dates of composition, but not on this page! Why don’t you see if you can guess some of the top songs before you look! When you're ready for the answers, click here. You can find more information at the ASCAP site.

|

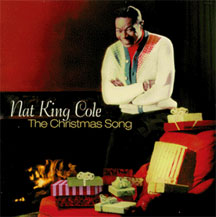

What are my own holiday favorites? I’m pretty much mainline here. At the top of my list would be: “The Christmas Song” (Nat King Cole’s version) and “White Christmas” (Bing Crosby’s version). These songs are great all by themselves, but their power is also in the memories they evoke of former Christmases. I don’t need a visit from The Ghost of Christmas Past to help me remember my childhood experiences of Christmas when I’ve got Bing and Nat to do it for me.

|

Here's one fine Christmas album! |

|

Home

Was the Night Really Silent?

Part 4 in the series “Christmas Carol Surprises”

Posted at 11:00 p.m. on Wednesday, December 22, 2004

Every year we sing it. We hear it in countless versions on the radio, in the mall, in television specials and popular movies. The song? “Silent Night, Holy Night” – the queen of the Christmas carols. No song, secular, sacred, or you name it, has been recorded more frequently. This is a fact, if you can trust the BBC. And, in my opinion, no song gets more airtime during the Christmas season than “Silent Night” in its multiple forms.

| The story behind the composition of “Silent Night” is a familiar one, though a few legendary bits have been added over time. What seems quite certain is this: In 1816 a young Austrian priest named Joseph Mohr composed a six-stanza Christmas poem that began “Stille Nacht, Heilige Nacht” (German for “Silent Night, Holy Night”). Two years later, on December 24, 1818, Mohr decided to have his poem sung in the Christmas Eve service of his church. So he went to his musically-inclined friend, Franz Gruber, and asked him to write a musical arrangement so they could sing it that night. Gruber obliged, and on Christmas Eve 1818 he and Mohr sang “Stille Nacht” in the midnight mass. Yes, they were accompanied by a guitar, but probably not because the organ was broken. Rather, it was common for music in the Austrian Christmas Eve mass to be of a folk variety. |

|

| |

The village of Oberndorf in the summer. Not bad!

|

Although “Stille Nacht” was not completely forgotten after 1818, it didn’t make the Austrian top-40 either, at least not right away. But a few years later some traveling folk singers added the song to their repertoire as a “Tyrolean Folk Song.” In this form it became well known, though a few notes were changed from Gruber’s original. (To hear the original tune and German lyrics, click here.) By the middle of the 19th century “Stille Nacht” was a favorite carol, having been sung even before the royal families of Europe. It was first performed in America in 1839 in New York City.

In the 19th century there was considerable debate about who had written “Stille Nacht.” Joseph Mohr had died, and Franz Gruber’s efforts to demonstrate his and Mohr’s authorship were only party successful. In recent times an old manuscript has convinced everyone that “Stille Nacht” was indeed written by Mohr and Gruber. (For a reliable historical account of “Silent Night,” see the informative piece by Bill Egan.)

Of course most English speakers know “Stille Nacht” not in its original German with six verses, but in a three-stanza version (sometimes four) that hails from the mid-19th century. The English translation captures the mood and basic idea of the German original, though with some curious changes, one of which I wish hadn’t been made.

For many years I used to fret about the implications of the first verse of “Silent Night”:

Silent night, holy night! All is calm, all is bright,

Round yon virgin mother and child! Holy Infant, so tender and mild,

Sleep in heavenly peace, Sleep in heavenly peace.

Was this an accurate representation of reality? I worried. After all, if you’ve ever been around newborn babies, you know that they tend not to sleep well at night. And when they don’t sleep, they often cry. Odds are pretty good that Jesus spent a chunk of Christmas night squalling, just like every other human baby. So was the night really silent? Did the holy family really sleep in heavenly peace, or was this some overly-romantic idealization? Worse yet, was it some Gnostic denial of Jesus’s full humanness? (Okay, I know that only Ebenezer Scrooge and I would dare question the theology of “Silent Night.” Humbug!)

A couple of years ago I made a discovery that answered my questions and soothed my conscience. I was serving as the volunteer music teacher in my kids’ public elementary school. I knew that if I taught my students a real Christmas carol this might make some people nervous, especially since I’m a pastor. So I decided to teach “Silent Night,” but in the original German. (I also taught my students “Hanukkah, Hanukkah” in Hebrew, just to balance things out.) While preparing for my lesson, I found the original German lyrics and did a rough translation. I was surprised at what I found. Here is my literal but non-singable translation of the first verse of “Stille Nacht”:

Stille Nacht! Heilige Nacht! Alles schläft; einsam wacht

Nur das traute heilige Paar. Holder Knab' im lockigten Haar,

Schlaf’ in himmlischer Ruh!

Silent night! Holy Night! Everyone is sleeping;

Only the beloved most holy pair is watching by themselves.

Blessed boy with curly hair, sleep in heavenly peace!

In this verse, the night is silent. But, the “holy pair” (Mary and Jesus) is not sleeping. They alone are awake. So the verse ends with an imperative: “Go to sleep, blessed boy with curly hair!” In other words, the German original makes it clear that Jesus is not some magic baby who sleeps soundlessly through his first night of life, but a real infant who fusses and needs encouragement to get to sleep. With the German original in mind, it’s easy to see that the first verse of the English translation preserves the imperative, though losing the fact that Jesus and his mother are still awake. (The English also loses the part about the curly hair.)

|

Whew! So “Silent Night” is okay after all! No over-idealized or even Gnostic Jesus, but a real human being. I only wish the second German verse had been translated into English. In this stanza the baby Jesus is laughing (!) as the good news of salvation issues from his mouth. Of course a newborn baby doesn’t laugh either, but I love the delightful picture of the laughing Jesus, historically accurate or not.

Much “Silent Night” lore is preserved in the Silent Night and Local Heritage Museum in Oberndorf, Austria. Also, there is a whole website dedicated to this carol, silentnightweb,with lots of resources, translations, etc. etc. The Hymns and Carols of Christmas website has eleven different English translations of “Stille Nacht.”

I want to close with one “Silent Night” story that, for me, is one of the most moving of all, though it’s relatively unfamiliar to most people. It comes from Stephen Ambrose’s stirring narrative of military life in World War II, Citizen Soldiers. The scene takes place in the freezing forest of Europe in the midst of heavy fighting between the German and American armies. The story comes from Lt. Charles Stockwell of the U.S. Army. |

The Silent Night Memorial Chapel in Oberndorf on Christmas Eve. |

|

Late on Christmas Eve, he was at a company HQ in a cellar. At about 2345 hours, the firing died down. “At the stroke of midnight, without an order or a request, dark figures emerged from the cellars. In the frosty gloom voices were raised in the old familiar Christmas carols. The heavy snowflakes fell softly, covering the weapons and signs of war. The infantry, in their frontline positions, could hear voices 200 yards away in the dark joining them, in German, in the words to ‘Silent Night.’ It was a time when all men could join in the holy and sacred memories of the story of the Christ Child, and renew a fervent prayer for peace, goodwill toward men.”

Amen to that!

Home

Hark the What? Ironies of a Beloved Carol

Part 5 in the series “Christmas Carol Surprises”

Posted at 11:30 p.m. on Thursday, December 23, 2004

Here’s a bit of sage pastoral advice: If you don’t want to tick people off, then don’t change the words of the hymns and carols. Throughout my pastoral career I’ve seen the opposite principle at work many times over: If you want to make folks mad, then change the words of their beloved songs. Sometimes even little changes, even the most sensible ones, will turn Christian saints into irate meanies.

There’s nothing new in this, you might be interested to know. Throughout Christian history people have been changing the music. And throughout Christian history others have been getting mad about it. When my church (0r our hymnal) makes some small change, usually trying to update unfamiliar language, almost always a few people will complain. Usually they’ll say something like this: “Why did you change the lyrics? Why can’t we just sing the original ones?” Yet in many cases the very words that people think are the original ones turn out not to be original at all. There’s no better illustration of this truth than the carol “Hark, the Herald Angels Sing.”

The story begins in the mid-18th century with the prolific hymn-writer Charles Wesley. Brother of the Methodist founder, John Wesley, Charles wrote literally thousands of hymns, including “Come, Thou Long Expected Jesus,” “Jesus Christ (Christ the Lord) is Risen Today,” and “O, for a Thousand Tongues to Sing.” One of his hymns, which he called, “Hymn for Christmas Day,” began this way:

Hark, how all the welkin rings,

"Glory to the King of kings;

Peace on earth, and mercy mild,

God and sinners reconcil'd!"

Joyful, all ye nations, rise,

Join the triumph of the skies;

Universal nature say,

"Christ the Lord is born to-day!"

Now that sounds an awful lot like “Hark, the Herald Angels Sing,” doesn’t it? In fact this is the precursor of our popular carol, the one that once flowed from the pen of Charles Wesley.

What in the world is welkin? you may wonder. It’s not actually in the world at all. “Welkin” is an archaic term for heaven or the vault of the sky. Originally, Wesley wasn’t thinking about angels singing, but the whole universe ringing with the good news of Christmas. (If you’d like to see the lyrics of Wesley’s original and hear one of the earlier tunes to which it was sung, click here.)

| So how did the welkin morph into singing angels? This was the editorial innovation of Charles Wesley’s close friend and fellow minister, George Whitefield. Whitefield omitted a couple of later verses and changed a few other lines, including “Hark, how all the welkin rings” to “Hark, the herald angels sing.” Quickly Whitefield’s version caught on, far outstripping Wesley’s original in popularity. Now you might think Wesley would have been grateful to his friend for helping this carol to soar in the polls. But if you did, you’d be completely wrong. In fact Wesley was peeved. He didn’t approve of Whitefield’s assertion that angels sang the good news of Christ’s birth because that wasn’t in the text of Luke. (In Luke 2:13 the angels are saying, not singing, “Glory to God in the highest.”) Of course when I last checked, “welkin” wasn’t in Luke 2 either. |

|

| |

Now here's an angel singing, whether it's in the text of Luke or not!

|

So the first irony of “Hark, the Herald Angels Sing” is that the words we know so well were not penned by the original writer, and he disliked what his friend the editor produced in their place.

The second irony has to do with the tune. We can’t be sure what tune Charles originally intended for “Hark, How All the Welkin Rings.” But Charles had specifically stated that this hymn required solemn, slow music. Nevertheless, in 1855, after Charles had gone to meet his Maker, an enterprising musician named William Cummings married the revised version of “Hark” to the music of Felix Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn had written a joyous piece of music for the celebration of the 400th anniversary of the inventing of printing. Cummings took this music and adapted it for the meter of “Hark, the Herald Angels Sing.” The result – which we know so well today – was magic.

Yet this is not something Mendelssohn anticipated, or even wanted. In a letter to his publisher in 1843, the composer said his song “will never do to sacred words.” His tune was appropriate for “something gay and popular” because the music was “soldierlike and buxom.” (Now when did you last see the words “gay,” “soldierlike,” and “buxom” in the same sentence? How times change!) Yet William Cummings took the song that Wesley wanted sung in a solemn manner, and the music Mendelssohn considered unfit for sacred themes, and blended them into a Christmas classic. Go figure!

Even in the form Charles Wesley didn’t like, “Hark, the Herald Angels Sing” still abounds with solid theology. More than almost any other Christmas carol, it expresses the theological heart of Christmas.

Hark! The herald angels sing, "Glory to the new-born King;

Peace on earth, and mercy mild, God and sinners reconciled!"

Joyful, all ye nations, rise. Join the triumph of the skies.

With angelic hosts proclaim, "Christ is born in Bethlehem!"

Hark! the herald angels sing, "Glory to the new-born King."

Christ, by highest heaven adored, Christ the everlasting lord

Late in time behold him come, Off-spring of the virgin's womb.

Veiled in flesh the Godhead see, Hail th' incarnate deity

Pleased as Man with men to dwell, Jesus our Emmanuel.

Hark the herald angels sing, "Glory to the new-born king!"

Hail the heav'n-born Prince of Peace, Hail, the Son of Righteousness

Light and life to all He brings, Ris'n with healing in His wings.

Mild He lays His throne on high, Born that man no more may die

Born to raise the sons of earth, Born to give them second birth.

Hark the herald angels sing, Glory to the new-born king.

Here we have such foundational themes as: reconciliation between God and sinners, the Incarnation, and the truth that Christ’s birth leads to new birth for us. As powerful as these themes are, consider the relatively unknown final stanzas of Charles Wesley’s original:

Come, desire of nations, come, Fix in us thy humble home;

Rise, the woman's conquering seed, Bruise in us the serpent's head.

Now display thy saving power, Ruin'd nature now restore;

Now in mystic union join Thine to ours, and ours to thine.

Adam's likeness, Lord, efface, Stamp thy image in its place.

Second Adam from above, Reinstate us in thy love.

Let us thee, though lost, regain, Thee, the life, the inner man:

O, to all thyself impart, Form'd in each believing heart.

Here is an astounding poetic statement of the broader implications of salvation. Not only do we inherit eternal life, but also through Christ, God restores “ruin’d nature” and joins us to himself in “mystic union.” Where we once bore “Adam’s likeness,” the likeness marred by sin, now we are formed in the image of the sinless Christ, the “Second Adam.” Someday, if I get enough courage, I’m going to have my congregation sing the full text of the “Hark” carol. I’ll leave in Whitefield’s edits, but add the final verses.

As you go to church tonight or tomorrow, most of the music will be familiar. Most of the words will be the same ones you sang when you were a child. But if it just so happens that a few words are different, remember the ironic story of the “Hark” carol, and rejoice that the astounding truth of Christmas can be expressed in such varied and magnificent ways!

With old words or new words, singing familiar carols or new songs, may you have a truly merry Christmas!

Note: The information in this post came mostly from three different sources: The New Oxford Book of Carols; Stories Behind the Best-Loved Songs of Christmas by Ace Collins; and the notes at The Hymns and Carols of Christmas website.

Home

Our Favorite Non-Carol Carol

Part 6 in the series “Christmas Carol Surprises”

Posted at 10:00 p.m. on Friday, December 24, 2004

We conclude every Christmas Eve service at my church with singing “Joy to the World!” It’s one of the great traditions of my life, using one of the greatest of all carols. “Joy to the World” gets both the message and the fundamental feeling of Christmas. Plus, it’s a blast to sing. Whoever wrote this carol certainly knew what he was doing.

Except he wasn’t writing a carol! Isaac Watts grew up in the Reformed/Puritan branch of Christianity in England. Folk of his theological persuasion used to believe that Christians should sing only the biblical Psalms in worship. No human composition could possibly compare, it was argued, to the truth and glory of God’s revealed Psalms. Yet there was a problem, in that many of the Psalms were not easily sung in their existing form. The meter just wasn’t right. So Reformed musicians recast the Psalms, changing words to get just the right meter. The meaning was still essentially the same, but the result was easy to sing in English. |

|

| |

Singing "Joy to the World" with bells ringing is most excellent! |

Nevertheless, the metrical psalms sung in church were a real bore, at least according to a young man named Isaac Watts. When he complained to his father about the music in church, his father challenged Isaac to write his own hymns. “See if you can do better,” the father said. And so Isaac set off to write some better hymns for worship. Write them he did! Watts ended up composing over 600 hymns, including some we still sing today, “O God Our Help in Ages Past” and “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross.”

Watts’s early efforts, however, were more in keeping with his Reformed background. In 1719 he published The Psalms of David, Imitated in the Language of the New Testament. In this collection of hymns, Watts used the biblical Psalms for his foundation. Then he rewrote the words, both so that the final result could be easily sung in English, and so that it reflected the reality of Christ. The result was a collection of metrical psalms “in the Language of the New Testament,” as Watts noted in his title.

One of these reframed psalms provides the text for our carol “Joy to the World.” This was not meant to be a Christmas carol at all. In fact, apart from the fact that “the Lord is come” and the overall sense of joy, there isn’t anything “Christmassy” about “Joy to the World.” Yet, for obvious reasons, it has become one of the most loved and most frequently sung of all Christmas carols.

In order for you to see the relationship between Psalm 98 and “Joy to the World,” I’m going to print the lyrics of the carol below, with cross references to verses from Psalm 98.

Joy to the world! The Lord is come.

Let earth receive her King;

Let every heart prepare Him room;

And heav’n and nature sing,

And heav’n and nature sing.

And heav’n and heav’n and nature sing. |

4 Make a joyful noise to the LORD, all the earth; break forth into joyous song and sing praises.

6 With trumpets and the sound of the horn make a joyful noise before the King, the LORD. 7 Let the sea roar, and all that fills it; the world and those who live in it. |

Joy to the world, the Savior reigns

Let men their songs employ.

While fields and floods,

Rocks, hills, and plains

Repeat the sounding joy,

Repeat the sounding joy

Repeat the sounding joy

|

2 The LORD hath made known his salvation (KJV)

8 Let the floods clap their hands; let the hills sing together for joy 9 at the presence of the LORD, for he is coming to judge the earth. |

No more let sin and sorrows grow,

Nor thorns infest the ground;

He comes to make His blessings flow

Far as the curse is found,

Far as the curse is found,

Far as, far as the curse is found. |

Here Watts strays farthest from the words of Psalm 98. |

He rules the world with truth and grace,

And makes the nations prove

The glories of His righteousness.

And wonders of His love,

And wonders of His love,

And wonders, wonders of His love. |

3 He hath remembered his mercy and his truth toward the house of Israel: all the ends of the earth have seen the salvation of our God. (KJV)

9 . . .for he is coming to judge the earth. He will judge the world with righteousness, and the peoples with equity. |

Though not written as a Christmas carol, “Joy to the World” gets to the heart of the matter. What are we celebrating this day? The entry of God into the world. Yes. The work of salvation begun. Yes. But, beyond that, we’re celebrating the glories of God’s righteousness. He who is righteous is also the one who makes us right in Christ. And we’re celebrating the fact that the Savior reigns. The kingdom of God has come in Christ. And we’re celebrating the wonders of God’s love. “For God so loved the world that he gave his only son, so that whoever believes in him may not die, but may have eternal life” (John 3:16). At Christmas we celebrate the first part of God’s giving his Son to and for the world. And all of this deserves lots and lots of joy!

May your celebration be rich, truthful, and joyful! Merry Christmas!

Home

The Strange Case of the Creeping Comma

Part 7 in the series “Christmas Carol Surprises”

Posted at 10:00 p.m. on Saturday, December 25, 2004

God rest you merry, gentlemen,

Let nothing you dismay,

For Jesus Christ our Saviour

Was born upon this day,

To save us all from Satan's power

When we were gone astray.

O tidings of comfort and joy,

For Jesus Christ our Saviour was born on Christmas day.

So begins one of the most familiar and beloved of carols. In America this classic carol surely makes the top-ten list. But in England it has been in the number one slot for two centuries! “God Rest You Merry Gentlemen” was in fact the only carol that actually made it into Charles Dickens’s classic story, A Christmas Carol. The song’s origins are unclear, but it was well known in the 19th century in many different versions, so it is surely much older than this. (The New Oxford Book of Carols includes three different versions.)

For most of my life when I sang this carol, I put a comma between “you” and “merry” – God rest you – comma -- merry gentlemen. So I sang the first line as if it meant, “God give you some good rest, gentlemen who are happy.” I figured that the merry gentlemen had exhausted themselves with Christmas shopping and partying and the like, so they could finally relax on Christmas day.

My meaning of the carol goes back a long time. Most of the old printings in the 18th century have the comma after “you.” But virtually all music historians agree that this was not the first sense of the line. Originally it read, “God rest you merry – comma -- gentlemen.” “To rest someone merry” meant “to keep someone happy.” In other words, this wasn’t a wish for happy people to rest, but for people to be and to keep on being happy because Christ is born. When you consider the rest of the lyrics, this makes the most sense. The best response to the birth of Jesus isn’t rest, but rejoicing.

However, if you’re like me, by Christmas day you need some rest too. I had four services on Christmas Eve, the last one ending at 12:15 on Christmas morning. Then I had a variety of fatherly duties at home. So I didn’t get to bed until 2:00 a.m. One of my favorite Christmas traditions is a nap in the afternoon, a little “God rest you” time. But this rest helps me to get into the real spirit of Christmas, the spirit “God rest you merry.”

So, this Christmas may you get some rest! More importantly, may God give you his joy, for “Jesus Christ our Savior was born upon this day!” |

|

| |

This version is from the 1860’s. The first line reads, “God rest you, merry gentlemen.” For a larger version, click here. |

Home

|