Blog Archive for 2/15/04 - 2/21/04

Reflection: How Can We Know Anything About the Real Jesus?

(Part 6)

Series: Questions and Answers About Jesus, Chapter 3, Part 6

Posted at 9:30 p.m. on Saturday, February 21, 2004

When we consider New Testament sources for knowledge of Jesus, immediately we think of the four gospels. Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John do indeed provide most of what we know about the life and ministry of Jesus. But from the rest of the New Testament we actually learn some of what is most important about Jesus.

People are often surprised to learn that the gospels are not the earliest writings of the New Testament. Though they tell the story of Jesus, they were written anywhere from thirty to sixty years after his death. Most of Paul's letters were written earlier, some less than twenty years after Jesus' death. Thus the oldest written information we have about Jesus comes in the Pauline letters.

Paul did not write much about Jesus' earthly life and ministry. He rarely quotes sayings of Jesus, though there are a few quotations (for example, 1 Corinthians 11:23-25) and a larger number of "echoes." The apostle did, however, frequently talk about the death and resurrection of Jesus. Take 1 Corinthians 15:1-6, for example. Here Paul writes:

1 Now I would remind you, brothers and sisters, of the good news that I proclaimed to you, which you in turn received, in which also you stand, 2 through which also you are being saved, if you hold firmly to the message that I proclaimed to you--unless you have come to believe in vain. 3 For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures, 4 and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures, 5 and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. 6 Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have died. 7 Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles.

When you peel back the theological interpretation, at the historical core Paul says that Christ died, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day, and that he appeared to Cephas (Peter) and many other disciples. There isn't anything about the life of Jesus here because Paul focuses on that which lies at the center of the Christian good news: the death and resurrection of Christ.

What's particularly noteworthy about this passage is that Paul didn't make it up when writing 1 Corinthians. He is reminding the Corinthians of what he had passed on to them previously, and this key content Paul received from Christians before him. In other words, this brief description of Jesus, which appears in a letter written about twenty years after his death, includes older oral traditions that have been passed on to Paul. In this passage, therefore, we glimpse one of the very oldest historical records about Jesus. And we see that the facts about Jesus have already been given a profound theological interpretation: Jesus died "for our sins in accordance with the scriptures," and he was raised "in accordance with the scriptures."

If we had time to comb through the rest of Paul's writings, and the rest of the New Testament writings besides the gospels, we'd find more about Jesus, but most of this material would concern, not his earthly life and ministry so much as his death and resurrection, and their meaning for salvation.

Why is this important to know? Well, for one thing it is reassuring for Christians to realize that the core of our faith lies in the oldest and most reliable portions of the New Testament. This is especially significant because there are scholars and pseudo-scholars who claim that the real Jesus was just a moral teacher, not a Savior who died for sins and was resurrected from the dead. But the facts run in the opposite direction. The earliest sources show that the center of early Christian belief in Jesus contained affirmations about his death and resurrection. These events were interpreted in the earliest days of Christianity as the way God had brought salvation to the world. From the early Christian perspective, Jesus was first of all the Messiah, the Savior, and the Lord.

In my next post I'll finally deal with the most extensive evidence we have for Jesus' life and ministry - the New Testament gospels.

Reflection: How Can We Know Anything About the Real Jesus?

(Part 5)

Series: Questions and Answers About Jesus, Chapter 3, Part 5

Posted at 9:20 p.m. on Friday, February 20, 2004

So far in this series "How Can We Know Anything About the Real Jesus?" I've examined Roman and Jewish sources from the first two centuries A.D. Not surprisingly, they don't have much to say about Jesus. But they do mention him as one called "Christ," who stirred up lots of his first-century followers, and who was killed under the authority of Pontius Pilate.

Beginning with this post I want to examine Christian sources for information about Jesus. Admittedly these sources are not neutral with respect to who Jesus was and what he did. But, as we have seen, neither are the Roman and Jewish sources.

Most of the second-century Christian writings, whether orthodox, heterodox (meaning "not orthodox"), or heretical, use the New Testament writings as their primary source for knowledge of Jesus. Thus they provide little more than evidence that the biblical writings were early and well-used. However, some of the non-biblical Christian writings may preserve traditions that were earlier than or distinct from the New Testament writings.

The Letters of Ignatius

Some scholars have argued, for example, that the letters of Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch in Syria, written around A.D. 110, preserve traditions about Jesus that are older than the New Testament gospels themselves. Thus the writings of Ignatius might serve as a witness to early sources of knowledge about Jesus.

What we find in Ignatius, however, confirms what we find in the biblical materials. In one of his letters, for example, Ignatius urges a church: "Be ye deaf therefore, when any man speaketh to you apart from Jesus Christ, who was of the race of David, who was the Son of Mary, who was truly born and ate and drank, was truly persecuted under Pontius Pilate, was truly crucified and died in the sight of those in heaven and those on earth and those under the earth; who moreover was truly raised from the dead" (Ignatius to the Trallians 9:1-2). These basic "facts" about Jesus are found throughout the earlier New Testament writings. Notice how Ignatius goes to great pains to point out that these things really happened. They were just figments of early Christian imagination.

The Non-Canonical Gospels

The vast majority of the non-canonical gospels are much later than the biblical gospels and derive their knowledge of Jesus from these earlier writings. It's possible however, that some of the extra-biblical gospels preserve historically accurate traditions about Jesus that were not preserved in the biblical materials. After all, Jesus said and did much more than could be squeezed into the four canonical gospels, as the Gospel of John clearly states (John 20:30). It's always possible that some of these sayings and actions were preserved in non-biblical sources.

The one non-canonical gospel that has the best chance of containing information about Jesus that is not dependent on the biblical gospels is The Gospel of Thomas , though many scholars have argued that the writer of this gospel in fact used the canonical gospels. Dating of The Gospel of Thomas is precarious and disputed, but it could have been written as early as the last decades of the first century A.D. More importantly, it seems to preserve traditions about Jesus that could be older and, in some cases, independent of the biblical gospels.

The Gospel of Thomas is a collection of 114 sayings attributed to Jesus. There is almost no narrative. A majority of the sayings are paralleled in the biblical gospels, sometimes quite closely. (See, for example, Thomas 20, which is the Parable of the Mustard Seed.) Many of the sayings in The Gospel of Thomas reflect Gnostic theology and surely didn't come from the mouth of Jesus. A few of the sayings, however, could reflect something Jesus actually said, even though not found in the biblical gospels. For example, "Jesus said, 'He who is near me is near the fire, and he who is far from me is far from the kingdom'" ( Thomas 82). We can't prove that Jesus said this, of course, but he might have.

The Gospel of Thomas , even though it paints Jesus with a Gnostic brush, nevertheless provides independent evidence that Jesus was a wise teacher who used clever sayings and parables to pass along his message. Central to this message was the proclamation of the "kingdom" of God - an authentic echo in Thomas of Jesus' own preaching.

Summary

|

If all we had were the second-century Christian writings, we'd have a hard time sorting out what Jesus really did and said. The gulf between orthodox and heterodox treatments of Jesus was wide and growing wider in this century as Gnostics claimed Jesus as their heavenly redeemer while orthodox Christians insisted that his ministry included far more than revelation. At it's core, they argued, it had to do with his death and resurrection, something the Gnostics rejected, prefering a revealer who didn't really suffer. But, I'm glad to say, we don't have only the second-century writings. In fact we have access to texts from the earliest days of Christian faith, writings which are collected in the New Testament. To these writings I'll turn in my next posts. |

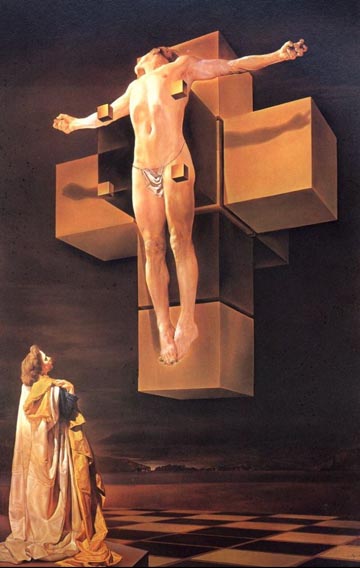

Salvador Dali's "Crucifixion" is a modern example of a Gnostic Christ, who does not really suffer. |

Reflection: How Can We Know Anything About the Real Jesus?

(Part 4)

Series: Questions and Answers About Jesus, Chapter 3, Part 4

Posted at 9:00 p.m. on Thursday, February 19, 2004

In my last post I finished looking at the evidence for Jesus from Roman sources. Now I will survey what we learn from Jewish sources (non-Christian Jewish sources, that is).

The Talmud

Jesus is mentioned occasionally in the Jewish Talmud, though often cryptically. Only a few passages appear to mention Jesus directly, and these - no surprise - are negative. For example, in one tractate of the Talmud its says that "Jesus the Nazarene practiced magic and led Israel astray" (b. Sanh. 107b). The Talmudic passages may preserve some genuine historical traditions about Jesus even though they were penned at least three centuries (or more) after his death.

But one Jewish writer in the first-century did mention Jesus in at least one passage, and probably two.

Josephus: Jewish Antiquities

In the early 90's of the first-century A.D., the Jewish historian Josephus wrote several treatises on Jewish history. He wrote to build bridges between Rome and the Jews, to explain why their relationship had been so rocky, and to iron out differences between them.

In one place in his Jewish Antiquities Josephus mentions Jesus indirectly. His focus is on the killing of James, who is identified as "the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ" (Ant. 20.9.1). In this context Josephus has no need to say more about Jesus himself.

The other passage where Josephus appears to mention Jesus is disputed because it comes to us only by way of medieval Christian sources, and these sources appear to have doctored the original text. Josephus is in the process of describing Jewish conditions under Pontius Pilate when we read:

Now there was about this time Jesus, a wise man, if it be lawful to call him a man; for he was a doer of wonderful works, a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew over to him both many of the Jews and many of the Gentiles. He was [the] Christ. And when Pilate, at the suggestion of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to the cross, those that loved him at the first did not forsake him; for he appeared to them alive again the third day; as the divine prophets had foretold these and ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him. And the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct at this day. (Ant. 18.3.3)

Given what we know about Josephus' beliefs (he was not a Christian), it's unlikely that this passage, in its current form, comes from his own hand. Many scholars believe that Josephus actually wrote about Jesus in this context, though without the obvious Christian touches.

Given uncertainty about the second passage, I do not want to claim too much about Josephus' knowledge of Jesus. He did know that Jesus "was called Christ." And he may well have known that Jesus was crucified under Pilate, but of this we cannot be certain.

Summing Up the Jewish Evidence: The Jewish evidence for Jesus is slight. This isn't surprising, really, because, apart from Josephus, we don't have literature from Jewish historians at this time. Jesus is surely known to the Rabbis cited in the Talmud, but their knowledge of Jesus is not independent of earlier sources. Moreover, given the conflicted relationship between Jews and Christians in the first few centuries A.D., we wouldn't expect them to say much about Jesus.

In my next post I'll examine Christian evidence for Jesus outside of the New Testament.

Reflection: How Can We Know Anything About the Real Jesus?

(Part 3)

Series: Questions and Answers About Jesus, Chapter 3, Part 3.

Posted at 10:20 p.m. on Wednesday, February 18, 2004

In my last post I began to examine the historical evidence for Jesus found in early Roman sources. Around 110 A.D. the Roman governor Pliny mentions "Christ" and early Christian belief in him. At about the same time the historian Suetonius refers to the expulsion of Jews from Rome in 49 A.D. According to Suetonius, the Emperor Claudius banished the Jews because they were being stirred up by someone called "Chrestus" or "Christus."

In addition to the references to Christ in Pliny and Suetonius, there are a couple hints about Jesus in the writings of Lucian of Samosata, Mara bar Serapion, and Julius Africanus, but these are too obscure to explore in this post. There is one relatively meaty passage, however, in the work of the historian Tacitus.

Tacitus: Annals

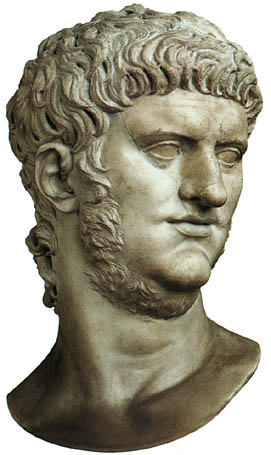

In 109 A.D., Tacitus wrote an extensive history of the first-century Roman Empire. In his discussion of the Emperor Nero, who reigned from 54-68 A.D., Tacitus reports that citizens were blaming Nero for the terrible Roman fire in 64 A.D. He decided to deflect criticism by blaming Christians. Here's Tacitus's description:

|

Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judaea, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular. (Ann. 15.44) |

Bust of Nero |

Apart from Tacitus' fascinating appraisal of Christianity as "a most mischievous superstition," he notes that Christ "suffered the extreme penalty" under Pontius Pilate - an obvious reference to Jesus' crucifixion. This does seem to fix the time of Jesus' death and the ultimate responsibility for that death.

Summing Up the Roman Evidence

There isn't really much Roman evidence to summarize. Jesus is rarely mentioned in Roman writings, though he does show up in a few scattered references. Why isn't Jesus discussed more often in this literature? The answer is simple: because he wasn't known or considered to be very important from the perspective of first- and second-century Roman history and government. He was simply one among many Jewish rabble rousers who had to be put down by the state. The fact that his followers were beginning to cause problems for Rome explains why Jesus was mentioned at all by Pliny, Suetonius, and Tacitus. But from the perspective of a leading Roman living around 110 A.D., Christianity was at most one of those annoying superstitions that disturbed Roman order and deserved to be squashed.

In my next post I'll look at Jewish sources of information on Jesus.

Reflection: How Can We Know Anything About the Real Jesus?

(Part 2)

Series: Questions and Answers About Jesus, Chapter 3, Part 2.

Posted at 10:30 p.m. on Tuesday, February 17, 2004

In my last post I clarified the purpose of my current mini-series: to answer the question "How can we know anything about the real Jesus?" In this post and the ones that follow I will provide a brief overview of the historical sources from which we derive information about Jesus. Today I'll begin to examine the evidence from earliest Roman writers who mention Jesus.

Ironically, all the three Romans who mentioned Jesus wrote about eighty years after his death - within a year or two of 110 A.D. Two of these writers were historians; one was a Roman governor who penned numerous letters.

A Letter from Pliny to Trajan

The governor was a man named Gaius Pilinius, whom we call Pliny the Younger (to distinguish him from his uncle, Pliny the Elder, a famous naturalist). The younger Pliny served as the Roman governor of Pontus and Bithynia (northern Turkey) from 111-113 A.D. During his tenure he wrote numerous letters, including a letter to the Emperor Trajan asking how he should deal with Christians who were accused of crimes against Rome.

Pliny's letter provides a fascinating glimpse of early Christian belief and behavior, though relatively little information about Jesus himself. Pliny states that Christians will never "curse Christ" and that they meet together each week, during which time they "sing responsively a hymn to Christ as to a god" (Letters, 10.96).

Pliny appears to have no knowledge of Jesus independent of what he has learned from Christians. Nevertheless, he documents that fact that they were becoming a problem in his region, and that they held Jesus in the highest regard, calling him "Christ" and worshipping him as God.

Suetonius: Life of Claudius

Around 110 A.D. the Roman historian Suetonius wrote a history of the Caesars. In his "Life of Claudius" he appears to mention Jesus, though in a peculiar passage. It reads: "Since the Jews constantly made disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus, he expelled them from Rome" ( Claudius , 25.4). Suetonius refers to an act of Claudius in 49 A.D. His use of the name "Chrestus" might refer to Christ, though the correct Latin name for Christ would be "Christus." Nevertheless, most scholars believe that Suetonius simply got the vowels confused (or his source did).

This passage shows how the Romans would have viewed Christians in the middle of the first century A.D. - as Jews who were making trouble because of somebody named Christ. Like Pliny, Suetonius appears to have no actual knowledge of Jesus. He may even have imagined Christ himself to be a rabble-rouser in Rome around 49 A.D.

I should note at this point a fact of early Christianity that is often ignored by Christians today: the earliest believers in Jesus were Jewish, and they considered belief in Jesus as the Messiah to be consistent with their Jewish faith and practice. Christianity emerged as a non-Jewish religion toward the end of the first century A.D., but it didn't begin there. This is a good reminder to all Christians of the debt we owe to the Jews.

In my next post I'll finish up my overview of the Roman evidence for Jesus.

Reflection: How Can We Know Anything About the Real Jesus? (Part 1)

Questions and Answers About Jesus, Chapter 3, Part 1

Posted at 9:30 p.m. on Monday, February 16, 2004

As we get closer to the release of The Passion of the Christ, more and more people will be talking and writing about Jesus. Opinions will differ, sometimes widely, about who Jesus was, what he did, and how all of this matters today. No doubt you'll run into claims that we really can't know very much about the real Jesus at all because our historical sources are too unreliable.

In this post and in those to follow I want to give a concise answer to the question: How can we know anything about the real Jesus? I will present a brief overview of the historical sources we have for knowledge of Jesus. As a Christian I believe that the New Testament gospels are divinely inspired and therefore trustworthy sources for knowledge of Jesus. But in this series of posts I want to consider the question of sources, not from the perspective of faith, but from the perspective of historical investigation.

Before I examine the sources, however, I need to make a couple of preliminary comments. First, I'm well aware that the topic I plan to consider in a few posts is one of the most complicated and convoluted in all of scholarship. The question of how we can know the truth about Jesus has spawned a centuries-long debate, and this debate is hardly over in scholarly circles. Nevertheless, I plan to address some of the main issues in a readable, concise, and useful manner. Obviously I'll be summarizing and offering my own conclusions, yet without giving you pages and pages of argument and evidence. (If you're interested in such detail, I'll point you in the right direction.)

Second, in the last two centuries the study of Jesus has been plagued with historical skepticism. It used to be the miracles of Jesus that led scholars to doubt the historical reliability of the gospels. More recently many have argued that the gospel writers have theological agendas, and these somehow get in the way of truthful history. But this begs the question, because if my theology values history, then my having a theological agenda might very well lead me to be a better historian, not a worse one. In a few posts I'll examine one of the "agendas" of a New Testament gospel, showing how this supports rather than undermines the historical reliability of the text.

But before I get to the New Testament gospels, I want first to look at the other ancient sources that tell us something about Jesus. I'll start with Roman sources, followed by Jewish writings, then Christian writings outside of the New Testament, then New Testament writings other than the gospels, and finally I'll consider the gospels themselves. After a brief survey of these materials you'll be able to answer the question: "How can we know anything about the real Jesus?"

I want to conclude with a word about why all of this matters. If we were Gnostics, we wouldn't give two cents for history. What matters to the Gnostic is spiritual revelation and insight. That's it. But Judaism and Christianity are rooted, not merely in ideas or subjective experiences, but in God's action within history. I'm not talking about raw history, of course, but historical events interpreted in light of God's revelation. It's a brute fact that "Christ died." But when St. Paul says that "Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures " (1 Cor 15:3), he is now interpreting an event from a divine point of view. Yet, even though the interpretation matters profoundly, so does the basic event. Thus knowing something about the real Jesus makes a real difference, not only for serious historians, but also for serious Christians.

Reflection: Gibson Speaks About the Passion

Posted at 10:00 p.m. on Sunday, February 15, 2004

In the Orange County Register today there is fascinating interview with Mel Gibson concerning his upcoming film, The Passion of Jesus Christ . I want to post some excerpts from "One Man's Passion" along with a few of my own comments.

Gibson on anti-Semitism: "Anti-Semitism is the deliberate abuse of Jewish people simply for being Jewish. That is not only stupid, it's morally wrong. By what I believe, it is not only boorish and bigoted, it is a sin. It is a moral crime. To be racist in any form is to be un-Christian."

My comment: I'm thankful for Gibson's strong denunciation of anti-Semitism. I hope other Christian leaders join him in making such a clear statement.

Gibson on the possibility of his movie inciting Christian anti-Semitism: "I have shown my movie to 20,000 Christians, and not a single person has expressed that kind of an emotion. Not even a hint. No one comes out of this movie hating the Jews. Of course, there always have been, and always will be, demented bigots amongst us. They're always there, but we can't let these morons dictate to us how we live, how we believe or how we express our art."

My comment: I think Gibson's estimation of the Christian response to The Passion is accurate. But I'm also glad that he is speaking out against the bigotry of anti-Semitism. Gibson owns the public pulpit right now, and his voice will be heard.

Gibson on Christian response to his movie: "If anything, I expect Christians to come out of this movie in an introspective mood. It is among the tenets of my faith that Jesus died for the sins of mankind. When you talk of culpability, I look at myself first, and I expect most Christians do the same. This is not about blaming anyone else."

My comment: Yes, this is precisely correct. I would add to Gibson's prediction, however. Christian's will leave The Passion not only in an introspective mood, but filled with awe and gratitude concerning the sacrifice of Christ.

On the rumor that Gibson deleted the line from the movie in which Jewish people say, "His blood be upon us and our children": "Gibson said that he has deleted a scene that has been interpreted by some to imply that a blood curse was placed on the Jews for their part in the Crucifixion. Gibson heatedly denied that the offending scene was intended to be interpreted that way but said he removed it in an attempt to "quell the fears. . . . I am not trying to play a game of hate and fear," he said, "so I took it out."

My comment: In an earlier post I responded to the story (at that time unconfirmed by Gibson) that he had removed this part of the movie. In the hope that this story was correct, I commended Gibson for "going the second" mile in his attempt to reach out to Jews and take seriously their concerns. Now I know that my commendation was appropriate. I'm grateful that Gibson put his desire to honor Jewish concerns above his artistic freedom. In doing this Gibson has shown himself to be, not only an exemplary filmmaker, but also an exemplary Christian.

What impresses me most about Mel Gibson's comments in this article is his willingness to respond to the real concerns of his critics without defensiveness or without attacking them back. Gibson admits that he has been deeply hurt by some of the accusations made against him. But, and this is key, he has not let that hurt govern his actions. Instead, he has listened sensitively to his critics and responded with kindness, even changing his movie - something most artists would never do.

I continue to be grateful to Mel Gibson, not only for his excellence as a filmmaker, but for his excellence in love as a follower of Jesus.

My other writings on The Passion of the Christ, including my in-depth review, can be found here.